By Nikita Mehandru[1] and Alexa Koenig[2]

Evidence derived from open sources—especially publicly accessible, online platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube—is becoming increasingly important for international criminal investigations and prosecutions. In this essay, we discuss how the International Criminal Court has recently incorporated open source information into its investigatory practices and how its emerging policies and procedures can contribute to the development of international guidance to advance the use of open source evidence in regional and national courts.

Introduction

On August 15, 2017, the Office of the Prosecutor at the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant, based heavily on information derived from social media, for Libyan military commander Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf Al-Werfalli.[3] Allegedly responsible for murder as a war crime connected to hostilities in Libya, Al-Werfalli reportedly committed or ordered the commission of murder in seven incidents against 33 people from June 3, 2016 to July 17, 2017 in Eastern Benghazi.[4] A video uploaded to Facebook on June 3, 2011 depicts one incident in which Al-Werfalli shouts to a hooded individual, “Put your hands up! Put your hands up! Put your hands up!” and subsequently shoots the hooded individual several times. Al-Werfalli then approaches the body, shoots again, and mutters, “You have been misled by he who did you harm. You have been misled by Satan.”[5]

With the realization that news often spreads faster on social media than through conventional media, and the unprecedented autonomy that comes with self-publishing, citizens are increasingly uploading vast amounts of digital imagery and videos to social media platforms to spread awareness of human rights violations and possible war crimes. Such footage has the power not only to bring attention to atrocities, but also to strengthen legal accountability processes if collected, preserved, transmitted, and analyzed in ways that adhere to the admissibility requirements for evidence in criminal and civil cases.

One challenge, however, is that content obtained from social media can raise issues of veracity, as metadata—information about content as well as non-content details such as when, where, how, and by whom the information was collected—is frequently stripped away and therefore cannot be used to corroborate critical information about the videographer and uploader, as well as the time, date, and place of filming. Thus, it is imperative to establish standards around corroboration and verification that help maximize the evidentiary weight of information derived from open sources.

In this essay, we discuss the significant and increasing potential for open source information derived from online platforms—which can include, but is not limited to, “profile pages, public messages, digital photographs, video, chat transcripts, [and other] messages” often secured from social media—to contribute to international criminal legal processes.[6] We also discuss the need for legal guidelines to support the proper collection, preservation, and analysis of digital open source information, how such guidelines might be developed, and the principles that could be incorporated to maximize the probative weight assigned to such information in court.

Types of Evidence

For the purposes of this essay, it is important to clarify what is meant by “open source information” and “open source investigations.” The term open source information is often used interchangeably with open source intelligence. However, open source information is publicly available information that can be obtained through observation, request or purchase, while open source intelligence is a subset of open source information that is used for intelligence purposes.[7] Importantly, open source information can come in various forms, including physical and electronic.[8] The focus of this essay is specifically on the latter: electronic information that is accessed through the internet. We focus on its use in online open source investigations: the process of identifying, collecting and/or analyzing information that is publicly available on the internet as part of the investigative process.[9] Open source information must also be distinguished from private and semi-private information. Examples of the latter two categories may be information communicated within closed Facebook groups or user generated content (such as videos) sent directly to organizations or individuals that are never released to the public.[10] However, such quasi-private and private information may still be verified or authenticated with the help of open source information. In addition, both semi-private and private information have been utilized by international courts and tribunals, sometimes in conjunction with open source information. Information that airs on public television stations, for example, would be considered open source information, while private videos would not.

There are also fundamental differences between physical and electronic evidence. Identifying and securing electronic evidence requires both machinery (hardware) and software.[11] This poses a challenge; as technology evolves, digital data may not be readable on all operating systems.[12] Aside from equipment and up-to-date software, it is imperative that the experts interpreting this data keep abreast of trends. In other words, having decades of experience in software development is of limited value if an individual does not know the most recent programming languages and applications.[13] Conversely, not knowing older platforms and languages can create significant hurdles, especially when cases are brought five, ten, or even thirty years after the alleged crimes, and information is stored on equally outdated hardware. In addition—and similar to biases evident in the interpretation of physical evidence—experts carry inherent prejudices that, in conjunction with analytical tools, can create flaws in how they interpret electronic evidence.[14] While little can be done to rectify this, acknowledging the issue can make users aware of potential pitfalls. The critical differences between electronic and physical evidence help account for the varied approaches in handling digital evidence across legal systems, including digital evidence derived from open sources.

International Criminal Law: The ICC and the Ad Hoc Tribunals

Though there is no overarching international standard for admitting video and photo evidence into court, the admissibility threshold in international tribunals is generally low relative to that in common law countries like the United States. The biggest challenges in international fora are establishing reliability and authenticity.[15] While information will often be admitted as evidence if shown to be even remotely relevant, the weight that judges will accord that information may vary.[16]

The ICC, as one of the most recently established international tribunals, has grappled with significant quantities of digital content, and as a result, has developed increasingly detailed requirements around the admissibility of electronic evidence. A number of the court’s regulations and processes are discussed below.

A. Admission of Evidence at the ICC

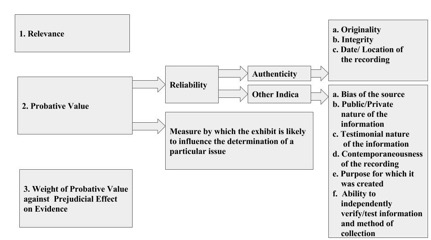

The ICC’s approach to the admission of evidence is outlined in the Rome Statute and the Rules of Procedure and Evidence, as well as its e-protocol.[17] For an item to be admitted into evidence it must satisfy a three-part test involving: (i) relevance, (ii) probative value, and (iii) absence of prejudicial effect.[18]

As for the first prong, the ICC defines relevance as making the “existence of a fact at issue more or less probable.”[19] The person or organization introducing the evidence, the plausibility, and the clarity established by a connection to the matter at hand, are crucial.

Probative value, the second prong, is comprised of two parts: a) reliability of the exhibit, and b) the extent to which the exhibit is likely to influence the determination of a particular issue.[20] The purpose of reliability is to determine whether a piece of evidence is what it purports to be. Reliability can be established in two ways: by authentication, the preferred method, or “other indicia,” as outlined in the chart below.

The purpose of authentication is to confirm that evidence has not been tampered with or manipulated. The ICC has developed specific markers of authenticity for open source, video, photographic, and audio-based information. With regard to open sources, verifiable information is needed that establishes where the item was obtained, or if no longer publicly available, then the date and location of acquisition. For video, film, photographic, or audio evidence, proving its origin and integrity (that it was not digitally altered) is recommended.[21] The ICC requires metadata be attached to all submissions, as well as documentation showing chain of custody, the identity of the source, the original author and recipient information, and the author and recipient’s respective organization.[22]

The ICC also offers alternative authentication methods, as outlined in the diagram above, that can establish the item’s probative value. Determining reliability and the evidence’s provenance, chain of custody, and content are crucial.[23] Experts are often required to articulate what information the evidence provides, versus what is a matter of mere speculation.[24] Courts have discretion, however, to exclude evidence that is unfairly and illegally obtained (e.g., via deception, surveillance, or theft), in violation of the accused’s or procedural rights, or that is irrelevant and repetitious.[25] The final weight afforded to that evidence is the paramount consideration, as most relevant information will be admitted.[26]

As for the third prong of the test, admitting the evidence must not have any prejudicial effect on the rights of the accused. Open source evidence may raise substantial concerns in this area, especially if the underlying information is compiled in such a way that it seems determinative of the case; editing can have substantial effects on the apparent guilt of a party in ways that are problematic because they may deviate from the objective truth underlying a particular event. In addition, because open source investigations consist of relatively new methods, opposing counsel (and chambers) may not have the necessary expertise to adequately interrogate how professionally and/or even-handedly those methods have been applied.

B. The ICC as a Standard Setter

The ICC saw its first case a few years after its establishment in 2002. The prosecution submitted video evidence alleging that Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, leader of the Uganda People’s Congress in the Democratic Republic of Congo, had enlisted soldiers under the age of fifteen to help establish the charge of conscripting child soldiers.[27] The images in the video strongly suggested that some of the soldiers were children, and in 2012, Lubanga was sentenced to fourteen years in prison, based in part on this critical evidence.[28] More recently, prosecutors have presented social media-based evidence before ICC judges. Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo, the former Vice-President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and leader of the Movement for the Liberation of Congo, was charged in 2008 with committing crimes against humanity and war crimes, including murder, rape, and pillaging.[29] The Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) seized a sizable amount of digital evidence, including Facebook photos in which two witnesses were visible. This was used to show that the two individuals had met and thus were linked.[30]

In 2013, the OTP vowed to focus even more on open source and other electronic information, creating a Digital Forensics Team within the Forensic Science Section (FSS).[31] The Director of the Investigation Division of the Office of the Prosecutor Michel de Smedt remarked: “usually there is a time gap of many years between the moment when the crimes are committed and the time the ICC investigators arrive. Cyber evidence can help to bridge this gap … People on the ground are more and more able to capture what’s going on.”[32]

Technology is shaping the next generation of documentary evidence in court, but such evidence is not without its flaws. Although digital evidence has the potential to alter case verdicts, skepticism about authenticity, a stigma against online sources, a lack of international lawyers trained in open source evidence collection and analysis, and the absence of an established scientific community with credibility to assess such evidence, hinders progress.

The ICC can play an important leadership role in this space by helping to address some of these challenges. This may include developing a public-facing version of standard operating procedures (SOPs) that can be shared with other courts that have a mandate to try grave international crimes, as well as hosting workshops to share knowledge between various war crimes units. Currently the OTP and its supporters are gathering information about how various units and courts are handling open source content and what additional guidance and training is needed. They are also participating in the development of an international protocol—to be released in late 2019—that can be used to help standardize open source investigations as a practice, and provide a basis for training. Information that comes out of those processes can go a long way towards standardizing and professionalizing the field, and increasing various groups’ capacities to use such methods efficiently and effectively.

Footnotes

[1] BA, Claremont McKenna College. Research Affiliate, Human Rights Center, UC Berkeley School of Law.

[2] JD, PhD, Executive Director, Human Rights Center and Lecturer-in Residence, UC Berkeley School of Law.

[3] Prosecutor v. Al-Werfalli, ICC-01/11-01/17, Warrant of Arrest (Aug. 15, 2017).

[4] The ICC issued a second arrest warrant in 2018 based on video evidence of subsequent killings. See Prosecutor v. Al-Werfalli, ICC-01/11-01/17, Second Warrant of Arrest (July 4, 2018), https://www.icc-cpi.int/CourtRecords/CR2018_03552.PDF.

[5] Al-Werfalli Warrant of Arrest, supra note 1, ¶ 11.

[6] Christopher Boehning and Daniel Toal, Authenticating Social Media Evidence, New York Law Journal, Oct. 2, 2012, https://www.law.com/newyorklawjournal/almID/1202573279324/?slreturn=20190218235324.

[7] Human Rights Center, UC Berkeley School of Law, International Protocol on Open Source Investigations: A Manual on the Effective Use of Open Source Information for International Criminal and Human Rights Investigations (forthcoming 2019).

[8] Id.

[9] In October 2017, experts from across the world convened in Bellagio, Italy to discuss a number of issues relevant to the use of online open source investigations conducted for legal accountability purposes. One of the tasks was to clarify key definitions, including the definition of open source information and online open source investigations. The definitions above are the definitions that the group produced. Those definitions, with commentary, are available in Human Rights Center, UC Berkeley School of Law, The New Forensics: Using Open Source Information to Investigate Grave Crimes 7–8 (2018), https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Bellagio_report_2018_9.pdf.

[10] Id.

[11] Stephen Mason and Daniel Seng, Electronic Evidence 21 (4th ed. 2017).

[12] Id. at 23.

[13] Id. at 24.

[14] Id. at 26.

[15] New Perimeter: DLA Piper’s Pro Global Bono Initiative, Using Photos and Videos as Evidence 3 (June 18, 2012) (on file with author).

[16] However, it is possible that this may change with the implementation of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which creates strict guidelines around accessing and storing content from social media given significant privacy concerns. See Commission Regulation 2016/679 of Apr. 27, 2016, Regulation on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (Data Protection Regulation), 2016 O.J. (L 119).

[17] Prosecutor v. Lubanga, ICC-01/04-01/06-1263-Anx1, Annex 1: Technical protocol for the provision of evidence, material witness and victims information in electronic form for their presentation during Trial (Apr. 4, 2008).

[18] Prosecutor v. Bemba, ICC-01/05-01/08, Decision on the admission into evidence of items deferred in the Chamber’s “Decision on the Prosecution’s Application for Admission of Materials into Evidence Pursuant to Article 64(9) of the Rome Statute,” ¶ 9 (June 27, 2013). Article 69(4) of the Rome Statute of the ICC further outlines that the Court may rule on the “relevance or admissibility of any evidence, taking into account, inter alia, the probative value of the evidence and any prejudice that such evidence may cause to a fair trial or to a fair evaluation of the testimony of a witness, in accordance with the Rules of Procedure and Evidence.” Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court art. 69(4) (July 17, 1998), U.N.T.S. 2187, No. 38544.

[19] DLA Piper, Evidentiary Holdings and Dicta…ICC 5 (on file with author).

[20] Id.

[21] See Prosecutor v. Katanga and Chui, ICC-01/04-01/07, Decision on the Prosecutor’s Bar Table Motions, ¶ 24(d) (Dec. 17, 2010).

[22] See Aida Ashouri, Caleb Bowers & Cherrie Warden, An Overview of the Use of Digital Evidence in International Criminal Courts, 11 Digital Evidence and Electronic Signature L.Rev. 115, 117 (2014).

[23] See International Bar Association, International Criminal Court, and International Criminal Law Programme, Evidence Matters in ICC Trials 20 (2016).

[24] Id.

[25] Using Photos and Videos as Evidence. supra note 13, at 10.

[26] See Ashouri et al., supra note 20, at 116.

[27] Benjamin Duerr, Can smartphones help ICC investigators?, Justice Hub (Sept. 15, 2015), https://justicehub.org/article/can-smart-phones-help-icc-investigators.

[28] Id.

[29] Prosecutor v. Bemba, ICC-01/05-01/08, Judgment pursuant to Article 74 of the Statute, ¶ 2 (Mar. 21, 2016).

[30] See, e.g., Lindsay Freeman, Digital Evidence and War Crimes Prosecutions: The Impact of Digital Technologies on International Criminal Investigations and Trials, 41 Fordham Int’l LJ 283, 328 (2018).

[31] Alexa Koenig et al, Human Rights Center, UC Berkeley School of Law, Digital Fingerprints: Using Electronic Evidence to Advance Prosecutions at the International Criminal Court 4 (2014), https://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/HRC/Digital_fingerprints_interior_cover2.pdf.

[32] See Duerr, supra note 25.