The following piece is published as an honorable mention in the Harvard Human Rights Journal’s Winter 2021 Essay Contest. The contest, Beyond the Headlines: Underrepresented Topics in Human Rights, sought to share the work of Harvard University students with a broader audience and shed light on important issues that popular media may overlook.

Perpetuating Islamophobic Discrimination in the United States: Examining the Relationship Between News, Social Media, and Hate Crimes

Janna Ramadan[*]

Abstract: Discrimination against minority communities and on the basis of religious identity violate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Following 9/11, the American public and greater Western world came to associate Islam and Muslim populations with terrorism. The introduction of bans on the burqa in France, oppression of Uyghur Muslim populations in China legitimized by a supposed threat of extremism, the Christchurch mosque shooting in New Zealand, and the U.S. Muslim ban display the degree to which the stereotype between Muslim populations and terrorism has permeated society, even to the level of domestic policy. Also important in perpetuating the association is the media, particularly social media.

To understand the degree to which social media influences or corroborates in the United States’ failure to secure basic human rights to its Muslim citizens and residents, this paper analyses the connection between media coverage and hate crimes in search for a predictive model and analyzes tweets to predict the average sentiment rating of tweets referring to Muslim populations or affiliated ethnic communities. The findings show no predictive relationship between media coverage and Anti-Islamic or Anti-Arab hate crimes but do predict a negative sentiment measure of tweets referring to the Muslim and affiliated communities.

Replication Materials: Data and code required to replicate analysis or further investigate claims made in this paper are accessible at https://jannaramadan.shinyapps.io/USIslamophobia/.

I. Introduction

In post-9/11 America, Muslims have been inextricably linked to terrorism in the public imagination. Americans have consumed media headlines about the Patriot Act, the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, violent extremist organizations, and the Muslim ban, all perpetuating an association between Muslims and terrorism. Explicit Islamophobic comments uttered by elected representatives have implied legitimacy to these stereotypes with former President Trump stating, “I think Islam hates us.”[1] Former Congressman Steve King also famously questioned the loyalty of elected Muslim-American Congressman Keith Ellison.[2]

Religion in the United States also carries a racial designation. Despite no one racial group constituting more than 30% of the Muslim population, Muslims are racialized as a community of color.[3] At the center of Islamophobia in the United States is a convergence of racial and religious discrimination. Hate crimes against Muslims in the United States are a violation of human rights rooted in discrimination and ostracization within American institutions.

Discrimination against minority communities and on the basis of religious identity is a violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[4] This paper seeks to investigate how media coverage of Muslims interacts with Anti-Islamic or Anti-Arab, as an affiliated ethnic community, hate crime rates and the social media rhetoric towards Muslims. It fills the gaps in existing studies on anti-Islamic hate crimes and media rhetoric complicity by centering its analysis on the United States.[5] Building on Twitter sentiment analysis on the topic of Islamophobia conducted in the United Kingdom, this project collects original data and seeks to predict the sentiment of tweets referring to Muslims and affiliated ethnic communities.[6]

Sentiment analyzing over 51,000 tweets and regressing 23 years of hate crime data on 12 years of media coverage records, this project finds that tweets containing references to Muslims, Islam, and related ethnic groups are predicted to carry a slight negative sentiment and that the frequency of media coverage of Muslims and terrorism does not predict anti-Islamic or anti-Arab hate crimes. Conclusions on the predictability of anti-South Asian hate crimes based on frequency of media coverage are not identified as the FBI does not separate anti-South Asian hate crimes from the broader anti-Asian hate crimes.

The discussion that follows has four parts: (1) current trends of hate crimes and media and social media coverage of Muslims and terrorism, (2) the design of the research project and data collection, (3) the main findings of hate crime and tweet sentiment predictability, and (4) a discussion of the broader implications of the findings and evident human rights failures of the United States regarding protection of its Muslim minority.

II. Current Trends in Hate Crimes, Search Interests, and Public Definitions of Terrorism

Findings from a 2019 report by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding found that fear of, and discrimination against, Muslims is on the rise in the United States. The trend is reflected in policy such as the Patriot Act and the 2017 Muslim Ban, which disproportionately targeted and impacted Muslim, Arab, and South Asian Americans, as well as the rise in hate crimes against Muslims and Arabs.[7]

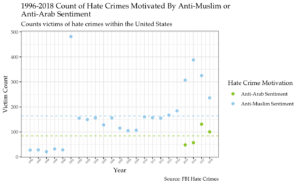

FBI hate crime data from 1995 shows a steady increase in anti-Islamic and anti-Arab motivated hate crimes (see Figure 1).[8] The dashed lines reflect the annual average number of hate crimes by motivation type. With the annual average anti-Islamic hate crime count at 163.78 hate crimes compared to the 84 annual anti-Arab hate crimes, there are more Islamophobic offenses recorded. However, note the similar trends in hate crimes. As anti-Islamic hate crimes increased between 2015 and 2016, so did anti-Arab motivated hate crimes. The parallel trend continued in the 2017-2018 hate crime decrease. Having only four years of collected anti-Arab hate crime data, the trend is not further corroborated in this project, but presents an interesting preliminary trend, reflecting conflation of Muslim and Arab identities.

Fig. 1

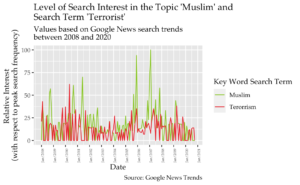

General media coverage trends on the topics of “Muslim” and “Terrorism” are garnered from Google News Trends of the United States from January 2008 to September 2020.[9] The similar “Muslim” and “Terrorism” search interest trends over a 12-year period display a clear association that reflects the American held association of Muslims and terrorism. When searches of news coverage on terrorism increase, so too do searches of news coverage on Muslims. This result reflects that internet users searching for news on Google in the United States actively search for both in tandem. This conclusion may come as a result of the searcher’s own perceptions of Islam and terrorism as related. It may also be a result of news coverage mentioning both topics, which further directs searchers to news coverage that presents terrorism as linked to Islam.

Fig. 2

Literature on how the American public defines terrorism further corroborates the trends displayed in hate crimes and media search interests. In an experimental study, researchers synthesized scholarly definitions and public debates to create predictions for how various attributes of incidents and perpetrators affect perceptions of whether the events were acts of terrorism.[10] They found that when perpetrators were described as Muslim, subjects were significantly more likely to classify a given event as terrorism.[11] In addition, perpetrators described as carrying foreign ties and the goal of changing policy have an 82% likelihood of being deemed perpetrators of terrorism.[12] Framing of events is an impactful exercise in both initiating and entrenching stereotypes linking Muslims to terrorism.

III. Method

This paper seeks to assess hate crime trends, search interest trends, and U.S.-based tweets on a series of keywords to investigate the predictability of anti-Islamic or anti-Arab hate crimes and the predictability of tweet sentiments.[13] Each of the two predictability questions is assessed utilizing different coding methods.

Predictability of Hate Crimes

As a research project focused on Islamophobia in the United States, FBI anti-Islamic and anti-Arab hate crime records between 1995 and 2018 present quantitative counts for discriminatory action while also cataloging events by motivation. Separating anti-Islamic and anti-Arab motivated hate crimes allowed the model to distinguish between religious and ethnic identities and compare predictability rates.

Due to a lack of quantitative values for news articles featuring the keywords “Muslim” and “Terrorism” at major news institutions, news coverage on Muslims and terrorism was represented by Google News search trends, displaying aggregate interest in the topics. The search results were also filtered geographically to only reflect searches within the United States. Using Google News search trends is advantageous in that it measures search interest on the basis of topics, aggregating clicks to all available news sources and reflecting public interest and engagement with the topics. However, Google News search trends do not reflect the content nor the descriptions of Muslims and terrorism in the news articles. Thus, this measure does not reflect the type of content searchers encounter.

Predictability of the count of hate crimes on the basis of news searches was then determined from the base beta values and range of the confidence intervals from the following Bayesian linear regression model: Counti = β1xmean_value + β2xkey_word – 1

Twitter Sentiment Analysis

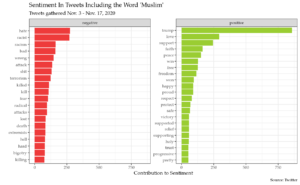

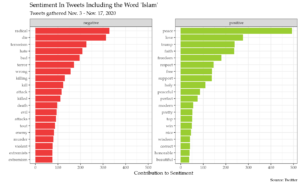

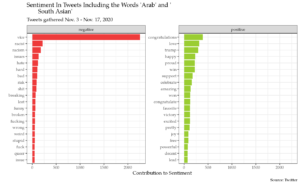

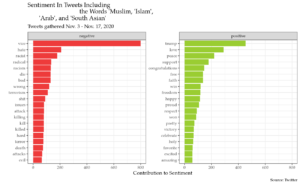

Scraping Twitter for English language tweets posted from accounts based in the United States that include key word groupings of “Muslim”, “Islam”, “Arab” or “South Asian”, and “Anti-Democratic” separately from November 3, 2020 to November 17, 2020, garnered 51,873 tweets.

After de-identifying the tweets and removing “stop words” such as “I”, “being”, “have”, etc., a bing text sentiment analysis was run to determine most frequent word associations, frequent word association sentiments, and general tweet sentiment of a 10-point numerical range.

Bing text analysis measures sentiments of words in each key word dataset in descending order of frequency on a 10-point scale, with word sentiment ratings ranging from -5, extremely negative, to 5, extremely positive. Sentiment ranges were weighed by term frequency to reflect the reality of the distribution. From there the data was bootstrapped 100 times to estimate the predictability of tweet sentiments based on keywords. The methods were repeated at the aggregate level for all ethno-religious keyword terms and aggregate of all key words.

Twitter data collection occurred before, during, and immediately after the United States 2020 election which impacted coding. Words such as “vice” for Vice President are coded negatively due to vice’s alternate definition associated with intoxicants. Likewise, the coding of “trump” as a word with a positive sentiment measure is not a reflection of political beliefs, but a reflection of the definition of the word trump.

IV. Findings

Predictability of Hate Crimes

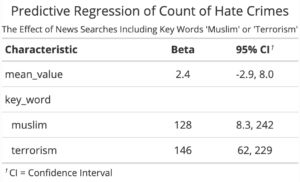

The regression model of count of anti-Islamic and anti-Arab hate crimes against variables of news searches count and searched topics found no causation relationship between the two (see Figure 3). The measure of mean value of hate crimes ranges from -2.8 to 7.9. The impacts of online searches including the word “Muslim” predict hate crime counts ranging from 6.1 to 266.6, looking at the range of the upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval. This trend follows on the searches including the term “Terrorism”. From the data, it cannot be concluded that frequency of searches including the words “Muslim” and “Terrorism” correlate with rises or decreases in anti-Islamic or anti-Arab hate crimes— a positive finding in light of the human rights issue of discriminatory action in the United States.

Fig. 3

Twitter Sentiment Analysis

Twitter sentiment analysis led to several findings beyond the central question of sentiment predictability.

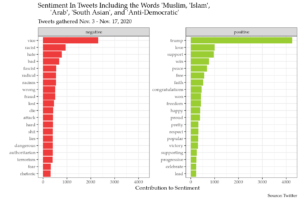

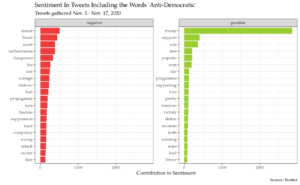

Excluding the words “vice” and “trump” due to their political meanings, comparisons of word associations to frequency, particularly for ethno-religious key words, highlight the greater frequency of negative sentiment words at the aggregate level (see Appendix A). Examining the top 20 most frequent positive and negative sentiment words, the volume of negative sentiment words is greater, particularly for the “Muslim” and “Anti-Democratic” key word and aggregate of the ethno-religious terms. Also notable was the degree of violent language referencing extremism, explicit language, authoritarianism, and death. Terrorism itself was the 18th most frequent negative sentiment word across the ethno-religious key words aggregate dataset.

In examining predictability through the bootstrapped dataset, tweets including the term “Anti-Democratic” are associated with the most negative sentiment words at -0.76. This should be taken in the context of the November 2020 elections, when this data was collected. In second place are tweets including the key words “Muslim” and “Islam”, with average weighted sentiments of -0.71 (see Figure 4). The bounds of all the tested key words never differ by more than 0.02, which indicates a very high confidence in the estimated sentiment values of words associated with tweets containing the studied key words.

Fig. 4

V. Broader Implications and Future Studies

Regarding the issue of discrimination against Muslim populations as an issue of human rights in the United States, the findings of this research present both positive and negative implications. Based on the analysis of anti-Islamic and anti-Arab hate crimes and news search interest of the topics “Muslim” and “Terrorism”, public news interest in Muslims does not predict discriminatory offenses. However, looking at the years in which hate crimes increase and news searches increase, there is a parallel. As terrorist events occur or elected officials speak negatively of Muslims and associated ethnic communities, discriminatory offenses rise as do internet news searches, a correlation.

The twitter sentiment analysis clearly displays that tweets referring to Muslims, Islam, and affiliated ethnic communities will predictably have a negative sentiment.

Although predicting more negative sentiments, the predictions of the term “Anti-Democratic” were significantly impacted by the election. Future studies should take into account the predictable current events when deciding keyword selection.

Remaining questions on the subject revolve around the causal versus correlated relationship between online rhetoric, across social media and news coverage, and anti-Islamic motivated violence. This study has found a strong correlation, and further research should center on testing a causal relationship to identify sources of anti-Islamic motivated violence, which may assist policy development efforts.

The treatment of all individuals as deserving of equal respect and freedom are central to the Declaration of Human Rights.[14] In neglecting the treatment of its Muslim citizens and allowing the perpetuation of Islamophobic rhetoric on online platforms, which correlates to in-person violent crimes rooted in hateful sentiment, the United States fails to secure the human rights of its own citizens. As a global hegemon, the U.S. is concerningly setting precedent for the mistreatment of Muslim minorities across developed and developing nations.

Appendix A.

[*] Harvard University, A.B. Candidate 2023.

[1] Jenna Johnson & Abigail Hauslohner, ‘I Think Islam Hates Us’: A Timeline of Trump’s Comments about Islam and Muslims, The Washington Post (Apr. 28, 2019) https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/post-politics/wp/2017/05/20/i-think-islam-hates-us-a-timeline-of-trumps-comments-about-islam-and-muslims/.

[2] Oscar Rickett, Steve King: Five Islamophobic Moments from Outgoing Congressman, Middle East Eye (June 3, 2020) https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/steve-king-five-islamophibic-moments-outgoing-congressman.

[3] Besheer Mohamed, A New Estimate of the U.S. Muslim Population, Pew Research Center (Jan. 6, 2016) https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/06/a-new-estimate-of-the-u-s-muslim-population/.

[4] UN OHCHR, A Special Focus on Discrimination https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/discrimination/pages/discrimination.aspx.

[5] Matthew L. Williams et al., Hate in the Machine: Anti-Black and Anti-Muslim Social Media Posts as Predictors of Offline Racially and Religiously Aggravated Crime, 60 Brit. J. of Criminology 93 (2020).

[6] Imran Awan, Islamophobia and Twitter: A Typology of Online Hate Against Muslims on Social Media, 6 Pol’y & Internet 133 (2014).

[7] Esther Yoon-Ji Kang, Study Shows Islamophobia Is Growing in The U.S. Some Say It’s Rising in Chicago, Too, NPR (May 3, 2019) https://www.npr.org/local/309/2019/05/03/720057760/study-shows-islamophobia-is-growing-in-the-u-s-some-say-it-s-rising-in-chicago-too.

[8] Federal Bureau of Investigation, Uniform Crime Reporting: Hate Crime (July 15, 2010) https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/.

[9] Google Trends, 01/01/2008 – 10/01/2020.

[10] Connor Huff & Joshua D. Kertzer, How the Public Defines Terrorism, 62 Am. J. of Pol. Sci. 55 (2018).

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Keywords tested: “Anti-Democratic”, “Arab”, “Islam”, “Muslim”, “South Asian”, and “Terrorism”.

[14]G.A. Res. 217 (III) A, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, art. 1, 7 (Dec. 10, 1948); see also OHCHR, supra note 4.