From Flores to Title 42: Unaccompanied Children in Detention

Ennely Medina*

I. Introduction

Following the CDC’s declaration of a global COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump Administration quickly reacted by enacting Title 42, a policy that permits the expulsion of migrants, including asylum-seeking unaccompanied children, without asylum screenings at the border. As immigration advocates highlight, Title 42 directly violates several domestic and international policies requiring the federal government to provide for the best interests of children in their care. Notably, Title 42’s use of hotel detention facilities along the southwestern United States fails to meet the standards set forth in the Flores Settlement Agreement of 1997, a class action suit which established licensed detention facilities and family reunification programs to serve the best interests of unaccompanied minors seeking asylum.

Since its enactment in 1997, the number of children in immigration custody has remained in a perpetual state of influx, permitting flexibility in the application of Flores that allows immigration officials to place children in unlicensed facilities during times of emergency and migrant surges. Through this loophole, the federal government was able to open its hotel detention program under Title 42, arguing that the United States was experiencing an influx of unaccompanied minors at the border and a national emergency due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, immigration advocates filed several ongoing lawsuits in favor of upholding Flores in these facilities, ultimately succeeding in receiving an injunction to end hotel detention.

Although, the battle to serve the best interests of unaccompanied minors is not yet won as the Biden Administration is now referring unaccompanied children to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) at an alarming rate, stimulating new fears for advocates. Searching for possible solutions, advocates are faced with difficult decisions on what legal strategies to take moving forward. In this essay, I will first outline the provisions set forth in Flores and how they have been applied since their enactment in the late 1990s. Second, I will provide an analysis of two cases—Flores v. Barr and P.J.E.S. v. Wolf—which were successful in applying Flores to repeal the hotel detention program of Title 42. And lastly, I will detail the effects of the Biden Administration’s detention process, promoting some possible solutions for legal advocates to consider as they seek to reform the unaccompanied child detention program.

II. Flores Settlement Agreement

To trace the evolution of child detention within the United States, one must discuss the Flores Settlement Agreement of 1997, which established a national precedent in limiting the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s (INS) ability to detain unaccompanied children for extended periods in restrictive settings. Prior to Flores, there were no regulations to maintain a safe standard of care for unaccompanied and accompanied children in detention.[1] Children were denied medical treatment, physical care, education, and recreational activities while in detention.[2] Flores, which stemmed from a 1985 class action complaint on behalf of several immigrant minors, including Jenny Lisette Flores, worked to resolve some of the issues of minor detainees in unsafe conditions. The original complaint stated several causes of action, the most egregious being incarceration with unrelated adults and strip/body cavity searches.[3] In the case of Ms. Flores, who was fifteen at the time of her detention, she was subjected to regular strip searches and forced to share close quarters with male adults.

a. Policy Objectives

Flores introduced a new era of regulation for child detention in the United States, setting standards that favor release to sponsors and require the federal government to place children in the “least restrictive setting appropriate for [their] age and special needs” so long as such setting ensures a child’s “timely appearance” before immigration courts for asylum or removal proceedings.[4] Further, children can only be detained in “safe and sanitary” facilities, licensed to provide residential, group, or foster care services.[5] Minors not released to sponsors remain in custody for the duration of their immigration proceedings, which can often take several months to resolve.[6]

b. Transition from INS to DHS

Although Flores lawyers tried to secure the best interests of children when drafting the settlement agreement, their policy objectives conflicted with the Department of Homeland Security, who after its establishment in 2002, took on a migration-deterrence approach and limited access to refugee and asylum processes. After the tragic events of September 11, 2001, the federal government enacted the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which dissolved the INS and established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in its place.[7] This overhaul of the nation’s immigration system resulted in the transfer of unaccompanied minors to a new government entity, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR).

Forming the Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) Program in 2003, ORR became responsible for coordinating and implementing the care of unaccompanied children, overseeing placement facilities, and “ensuring that the interests of [children] are considered in decisions and actions relat[ing] to [their] care and custody.”[8] Incorporating the provisions from Flores, the UAC Program sets out to place children in the least restrictive settings to serve their best interests.

Since 2003, most unaccompanied children in ORR custody are placed in shelter facilities. Expanding from 25 facilities to over 170 in the span of 18 years (2003-2021), the ORR vaguely defines shelters as residential care facilities that provide services on-site in the least restrictive setting possible.[9] Pursuant to Flores, these facilities are state-licensed (through state-specific child welfare laws) and offer services like classroom education, recreation, health services, case management, and assist in family reunification.[10] Although, as the numbers of detained unaccompanied children continue to rise, the ORR is increasingly relying on influx shelters to house children crossing the border.[11]

c. “Influx” Exception to Flores

To ensure the safety of unaccompanied minors after apprehension, Flores stipulates that transfers to licensed facilities must occur within 72 hours (3 days) of apprehension in a region with an accessible licensed program or within 120 hours (5 days) if a licensed program is inaccessible.[12] The main exception to this rule that would justify an extension of apprehensive custody is an “emergency” or an “influx” of minors entering the United States. Flores defines an emergency as any act or event preventing the placement of minors in licensed programs, including natural disasters, civil disturbances, and medical emergencies.[13] In the context of child detention, an influx occurs when more than 130 minors are eligible at once for placement in a licensed program.[14]

Over the last three decades, worsening poverty, violence, and corruption within the Northern Triangle countries (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador) and Mexico pushed families and unaccompanied children to flee to the United States in search of better opportunities. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, political conflicts between conservative political elites and leftist radicals in countries like Guatemala and El Salvador became full-scale civil wars, significantly reducing the quality of life for their citizens.[15] These civil wars continue to impact Central American countries well into the 21st century, resulting in scarce resources and acts of state-sanctioned violence against those who oppose the current political regimes of each respective country.[16] Without many options at home, families are fleeing to the United States at higher rates each year as country conditions worsen.[17]

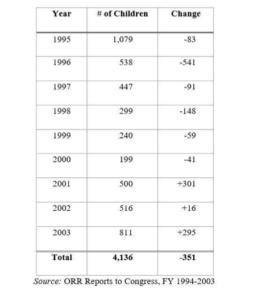

As more families enter the United States, the population of minors eligible for detention remains in a state of perpetual flux, allowing immigration officials to establish unregulated influx shelters and detain children in poor conditions. Under Flores, influx shelters do not need licenses to operate, ultimately providing less protection and resources for unaccompanied children.[18] While the exact number of children placed in influx shelters post-Flores is difficult to discern, it is alarming to compare the number of children placed in licensed welfare programs in 1998 (first full year after Flores) to the total number of child detainees that same year: while the INS reported detaining 5,300 children in 1998, only 299 were placed in licensed welfare programs.[19] This trend continued into the 2000s.[20]

|

d. Expansion of Unaccompanied Child Detention in Influx Shelters

Through its delegative authority from DHS under the Homeland Security Act, the ORR establishes influx shelters across the country (particularly near the southern border) to temporarily house influxes of unaccompanied minors. It is difficult to find statistical evidence on the exact number of children who spend time within influx shelters each year; however, some influx shelters report such data on an individual basis.[21] For example, at the Homestead Job Corps Site, located in Homestead, Florida, the ORR placed over 8,500 unaccompanied children in their emergency care from June 2016 to April 2017.[22] From March 2018 through July 2019, 14,300 unaccompanied children were placed in Homestead.[23]

Influx shelters are notoriously known for their poor internal conditions, often depicted in the media as children laying on cots with foil blankets (see image below). Because these shelters do not have to abide by Flores’s standards of care or licensing requirements,[24] unaccompanied children in their care are deprived of necessities like adequate healthcare and access to clean water, resulting in high rates of illness and in some cases, death.[25] These health consequences have only worsened now during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a rationale for the Trump Administration to apply Title 42 restrictions and limit the detention of unaccompanied minors.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection

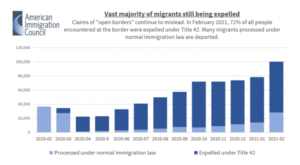

III. Title 42

Following the World Health Organization’s declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic, countries across the world began shutting their borders to incoming migrants under the guise of “slowing the spread” of COVID-19.[26] The United States quickly followed, with the Trump administrating announcing its “Title 42 Process” on March 21, 2020.[27] Under this process, travel primarily across the U.S.-Mexico border was restricted to only essential travel for services requiring food, fuel, and healthcare.[28] However, the lasting effect of this process was the suspension of asylum processing for refugees and unaccompanied children, resulting in their immediate expulsion to their countries of last transit.[29] From March 20, 2020 through October 2020, over 200,000 immigrants were expelled (see image below).[30]

a. Policy Objectives

Title 42 of the United States Code §265 was initially passed in 1944, codifying the Public Health Act to establish a “summary immigration expulsion process” during healthcare crises.[31] It permits the Surgeon General, acting pursuant to regulations approved by the President, to “prohibit . . . the introduction of persons and property from such countries or places as he shall designate in order to avert [the] danger [of spreading communicable disease], and for such period of time as he may deem necessary.”[32] Using this language, President Trump instructed the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to effectively suspend the introduction of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border to prevent the spread of COVID-19.[33]

The policy objectives behind the March 2020 enactment of Title 42 were primarily to preserve the health and safety of Americans, not of incoming migrants. Although the actual language of Title 42 is neutral on its face, the Notice of Order under which it was implemented last year reads as anti-immigrant, concerned only with the transmission and spread of COVID-19 to Customs and Border Protection (CBP personnel), U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, and other persons working at immigration facilities.[34] Immigrants are described as “aliens who lack valid travel documents and are therefore inadmissible,”[35] proscribing to the rhetoric of the illegal alien[36] and dismissing the humanitarian reasons for their plight. Further, their admission is described as taking resources away from Americans, as COVID-19 immigrants would “exhaust the local or regional healthcare resources, or at least reduce the availability of such resources to the domestic population.”[37] As immigration advocates predicted, Title 42’s effects went beyond its proposed purpose of preserving health and safety, effectively terminating asylum processing for tens of thousands of families and children,[38] and also exacerbating anti-immigrant sentiments pre-existent in the Trump Administration.[39]

b. Effects on Asylum Processing

Because of Title 42’s mass expulsion orders, CBP officials at ports of entry (POE) are expelling families without conducting non-refoulement screenings to determine if they are eligible for asylum.[40] A leaked CBP memo providing guidance on expulsions gives agents wide discretion in deciding when to conduct screenings, instead placing the burden on asylum seekers to make “affirmative, spontaneous, and reasonably believable claim[s]” of torture in their home country.[41] By denying screenings to possibly eligible immigrants, CBP is directly violating mandated procedural safeguards under the 1980 Refugee Act. The Act intended to prevent such abuse of discretion and preserve the integrity of asylum seekers by ensuring due process in processing their claims of abuse and torture.[42]

Furthermore, Title 42 also infringes on international human rights law to which the United States is a party, including the Convention against Torture and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, prohibiting expulsions to conditions where migrant families would face significant risk of ill-treatment.[43] Under Title 42, asylum seekers are expelled to their country of last transit (usually Mexico), where they do not have legal status and are unable to work or access necessary services. Human Rights Watch reports that Central American migrant families in Mexico are victims of persecution by Mexican authorities, who detain and expel them back to their home countries despite their expressed fears of torture and abuse upon their return.[44]

In some cases, families stuck in Mexico attempt to enter the United States outside of POEs, risking their lives to cross the U.S.-Mexico border through remote areas with dangerous conditions of high temperatures and treacherous waterways.[45] On March 20, 2021, a mother and her two children (aged nine years old and three years old) were found unconscious by the Rio Grande River along the border in Roma, Texas—the nine year old child was pronounced dead at the scene.[46] More stories like this riddle the border, demonstrating how desperate migrant families are to escape the poor conditions of their country and seek asylum in the United States.

c. Decreased Detention of Unaccompanied Children

Following the enactment of Title 42, rates of unaccompanied child detention decreased as CBP officials expelled more families and children prior to entering the United States. In FY 2019, the ORR received a record high of 69,488 referrals to the UAC program.[47] In FY 2020, when experts predicted a surge in the rate of unaccompanied children crossing the border (due to worsening home country conditions in the Northern Triangle),[48] the number drastically dropped to 15,381 referrals.[49] Inversely, the rate of expulsions increased to over 13,000 children from March to November 2020, a direct result of Title 42 processes on the southern border.[50] In late 2020, the Guardian reported that more than 1,400 unaccompanied children were deported to Guatemala since Title 42’s implementation, a stark contrast from the 385 children deported in 2019.[51]

Asylum seeking parents, who are often denied asylum themselves, are self-separating from their children and letting them cross the southern border alone, trusting the U.S. government will provide shelter for them and guide them through the asylum process. However, because immigration officials are following orders of direct expulsion without conducting asylum screenings (under the guise of stopping the spread of COVID-19), they are not ensuring the safety of expelled children. While they wait for their expulsion, children are isolated in hotel rooms in Arizona and Texas rather than placed in ORR custody, violating the standards of care set forth in Flores and affirmed in TVPRA.[52]

In Flores v. Barr, DHS contended that the Flores agreement did not preclude their detention of unaccompanied minors in hotel rooms.[53] COVID-19 made it difficult for them to place children in close quarters at ORR licensed facilities, and as such, they sought an alternative route to detain unaccompanied children that complied with Flores.[54] In response, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a statement condemning the use of hotels to detain children, claiming the lack of welfare regulations did not serve the best interests of unaccompanied children and instead harmed their psychological health.[55]

Moreover, children return to unsafe conditions in their home countries or countries of last transit, and often, they are not reunited with family members.[56] In one story, Sandra Rodriguez, a woman from Honduras seeking asylum in the United States, instructed her ten year old son Gerson to cross the Rio Grande alone, believing he had a better chance of receiving asylum as an unaccompanied child and would be united with his uncle in Houston as his sponsor.[57] But after six days, Ms. Rodriguez received no word on whether he was taken into custody, nor if he was placed with his uncle. Instead, she received a phone call from her cousin in Honduras, claiming she had Gerson with her, crying and disoriented after being flown back to the “dangerous place he had fled.”[58] Gerson’s story illustrates the terrifying experiences of expelled children, harms that government officials fail to consider in their implementation of Title 42.

IV. Flores Challenges to Title 42

Following a court-ordered investigation into the detention conditions of several children staying in hotels across the southwestern United States, Dr. Paul Wise (court-appointed Special Expert in pediatrics) and Andrea Ordin (Flores Independent Monitor) were granted access to three hotels in McAllen, Texas, El Paso, Texas, and Phoenix, Arizona.[59] On July 22, 2020, they filed their Interim Report on the Use of Temporary Housing for Minors and Families under Title 42, sparking outrage among immigration advocates concerned over violations of the Flores Settlement Agreement’s care provisions.[60] The report stimulated an onslaught of litigation against Title 42’s procedures, as evidenced by two cases—Flores v. Barr and P.J.E.S. v. Wolf. Ultimately, these efforts were successful in obtaining a federal injunction to stop Title 42 hotel detentions, implemented by September 15, 2020.[61]

a. Flores v. Barr

Under the Flores Settlement Agreement, several immigration advocacy groups[62] filed a suit to enforce the Agreement’s care provisions in hotel facilities, claiming that holding unaccompanied minors in unlicensed hotels for prolonged periods violated their best interests.[63] Taking the Independent Monitor’s findings into account, they argued unaccompanied minors should be excluded from Title 42’s application and hotel detention process, as immigration officials provided “no assurance that the hoteling program can provide adequate custodial care for single minors.”[64] As evidence of Title 42’s violation of the Flores Settlement Agreement, the plaintiffs divided their argument into three categories, detailed below.

1. Placement in a Licensed Program

The plaintiffs argued that the government’s use of unlicensed hotel facilities to detain unaccompanied children was a Flores violation. Because the hotel facilities were run by a DHS contractor (MVM) and were not state-licensed as required under Flores, children in their detention were deprived of “individualized needs assessment[s], educational services, daily outdoor activity, and counseling sessions.”[65] Further, Flores required that stays in influx shelters (as the government claims these hotels are classified as) be at most between 72 and 120 hours long; as the Interim Report detailed, children were multiple days in hotel rooms at times.[66]

Although the plaintiffs and the Court acknowledged that COVID-19 presented an “emergency” situation that would permissibly slow the rate of child transfers to ORR custody, the Court held that the defendants failed to demonstrate how hotels, rather than licensed facilities, were mitigating the risk of COVID-19 infection among child detainees.[67] As the Interim Report detailed, ORR shelters were 97% vacant as of August 22, 2020, providing ample room to accept unaccompanied children and maintain social distancing without “making a dent in the facilities’ capacity.” [68] Therefore, the Court ruled that the defendants breached Flores in this aspect.

2. Safe and Sanitary Conditions

Flores also requires that detention conditions be “safe and sanitary” and recognized the “particular vulnerability of minors,” including protecting children from illness or injury.[69] While the Court upheld the hotel facilities’ regular cleanings and hygiene provisions as sufficiently “sanitary,” it refused to uphold they were operating safely.[70] For children to be “safe” in the eyes of Flores, immigration officials must assess the “particular vulnerability of minors” and individualize care for each detained child.[71] The immigration officials maintaining the hotel facilities, however, failed to take an individualized approach and had no separate standards of care for particularly vulnerable children (as young as ten years old and/or with significant developmental differences).[72] Additionally, the unaccompanied children in hotels were under the supervision of private contractors, called “Transportation Specialists,” that had no qualifications or training in child development.[73] As such, the Court found the hotels’ conditions were not adequately safe.

3. Access to Counsel

Lastly, Flores entitles unaccompanied children in detention visits with counsel, at minimum that can be satisfied with “one phone call a day.”[74] Following Title 42’s implementation, legal service providers reported “unusual difficulty locating children within Title 42 custody,” attesting that often DHS officials were unable to provide accurate information on a child’s location (which hotel they were placed at).[75] The Court found that because immigration officials provided no notice to unaccompanied children’s counsel, they did not abide by Flores.

In conclusion, the Court decided that because all minors in the legal custody of DHS pursuant to Title 42 were class members protected through Flores, the federal government and its officials must comply with Flores’s standards of care.[76] Therefore, they must “cease placing minors at hotels” by no later than September 15, 2020.[77]

b. J.E.S. v. Wolf

In P.J.E.S. v. Wolf, the plaintiff attorneys sought to receive a preliminary injunction to halt the expulsion of children pursuant to Title 42. Citing the decision in Flores v. Barr, the court agreed that the detention of children in hotel facilities violated the standards of care set forth in Flores. Reiterating what that court outlined before, they explained:

The government had failed to demonstrate how hotels, which are otherwise open to the public and have unlicensed staff coming in and out, located in areas with high incidence of COVID-19, are any better for protecting public health than licensed facilities would be” and that “[e]ven if the infection control protocols at [the Office of Refugee Resettlement] come under stress, or are forced to make some adjustments,” the program’s facilities are likely to “remain far safer than unregulated hotel stays for both detained minors and the general public.”[78]

In terms of Title 42 expulsions of unaccompanied children, the court did not buy the government’s argument that the Title 42 process preserved the safety of CBP officials from COVID-19 infections. Instead, the court held that immigration officials had many “tools at [their] disposal” to limit the entry of undocumented migrants that did not mandate the expulsion of unaccompanied children.[79] The court granted the preliminary injunction on November 18, 2020.[80]

V. Post-Injunction and Biden Era Effects on Detention

Although Title 42 no longer applies to unaccompanied children under Flores v. Barr and P.J.E.S. v. Wolf, the Biden administration continues to apply it to adults accompanying children at the border, resulting in further family separations. As legal advocates stress, these separations, though seemingly well-intentioned to protect children from predatory violence in the Mexican desert,[81] may harm children more than help them. Detailed in a 2019 HHS report, the first significant acknowledgment by the U.S. government on the mental health conditions of unaccompanied children, family separation causes irreparable damage to children’s developing brains and is linked to higher rates of PTSD and chronic depression among children.[82] As PHR Asylum Network officer Kathryn Hampton explains:

The special bond between parent and child is imperative to healthy cognitive and mental development. Parents help buffer children from extremely stressful and dangerous situations. Without this vital resource, children are at risk of devastating short- and long-term mental and physical harm . . . . Family unity is recognized as a civil right under the U.S. constitution and under international law. Children should only be separated from parents in cases where it is in the child’s best interest to keep them safe. Under no circumstances should it be U.S. policy to traumatize children and their families.[83]

Following the injunctions on hotel detention and expulsion of unaccompanied children under Title 42, the number of children in ORR custody has risen significantly as the Biden administration transitions its immigration forces. In March 2021, 18, 890 unaccompanied children successfully crossed the U.S.-Mexico border; a one-hundred percent increase from February 2021.[84] Although the number of unaccompanied children in detention at Border Patrol stations and tent facilities decreased by more than half in April 2021,[85] HHS reported it received 122,000 migrant children into custody during the 2021 fiscal year.[86] In light of the Biden’s administration court-ordered inability to expel families or unaccompanied children under Title 42,[87] the increasing number of child detainees in indicative of larger issues that the mere repeal of Title 42 cannot resolve. Because Title 42 expulsion still applies to single adults, many families arriving at the border have made the “devastating decision, calculated only out of desperation, to send their children off ahead of them, alone, to cross the border.”[88] Accordingly, the solution to ending family separation requires more than repealing Title 42.

VI. Next Steps for Legal Advocates

Title 42’s enforcement is only exacerbating issues rising from family separation, and for that reason, it should not be enforced. Although it was outwardly enforced to prevent the spread of COVID-19, the positivity rates of immigrants in detention remains low (less than twelve percent),[89] especially when compared to the positivity rates of the greater American population.[90] Instead, his policy serves as yet another tool in our immigration regime, used to advance anti-immigration rhetoric and xenophobia that harm asylum seekers looking for better conditions to raise their families. Rather than end family separation, as Biden promised on the campaign trail, his administration is continuing Trump’s legacy, worsening conditions at the border as families forcibly separate[91]

Legal advocates seeking to end family separation should not only advocate to repeal Title 42 but should also push the Biden administration to undertake more appropriate solutions to the surmounting number of families seeking asylum. Some possible solutions the administration could undertake include utilizing the resources in place to house families, rather than expelling parents and guardians while detaining children in the country. The government could also ensure proper housing for asylum seekers while addressing public health concerns arising from COVID-19, providing COVID-19 vaccines, testing, and social distancing to migrants in open facilities (rather than expelling them into unknown conditions in non-origin locations).

Another option legal advocates may seek, in conjunction with family detention, is the use of a case-management system that allows migrants (parents and children) to shelter with their families or close contacts within the United States.[92] Similar to the existing ORR sponsor program for unaccompanied children, releasing families to sponsors may benefit them long-term, allowing them to provide for themselves as they await asylum determinations. The resources for these solutions exist yet are not utilized to date. For instance, each year, thousands of beds in immigrant detention centers go unused—in May 2020, ICE spent $20.5 million for over 12,000 unused beds.[93]

Ending family separation is paramount to preserving the best interests of unaccompanied children seeking asylum in the United States. Therefore, policies like Title 42, which only worsen conditions for children both inside and outside detention, should no longer be enforced.

[*] Ennely is a J.D. candidate, class of 2023, at Harvard Law School, where she serves as Editor-in-Chief of the Harvard International Law Journal and is an active member of First Class and La Alianza. Her passions include serving her community, and she is interested in international criminal law, human rights law, immigration law, and legal advocacy. Prior to law school, she graduated from Northwestern University in 2019, where she focused her honors research on the detention of immigrant children, and she previously served as a Sponsors for Educational Opportunity (SEO) Law Fellow in 2020, through which she worked as a Summer Associate at White & Case, LLC in 2020 and 2021. She will be returning to White & Case, LLC in the summer of 2022.

[1] Jasmine Aguilera, Body Cavity Searches, Indefinite Detention and No Visitations Allowed: What Conditions Were Like for Migrant Kids Before the Flores Agreement, Time (Aug. 21, 2019, 7:12 PM), https://time.com/5657538/flores-settlement-agreement-standards/ [https://perma.cc/3JET-LP5U].

[2] Id.

[3] Complaint at 27–28, Flores v. Meese, 681 F. Supp. 665 (C.D. Cal. 1988).

[4] Sarah Herman Peck & Ben Harrington, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R45297, The “Flores Settlement” and Alien Families Apprehended at the U.S. Border: Frequently Asked Questions 7 (2018).

[5] Id.

[6] The average length of custody has increased from 33 days in FY 2000 to 72 days in FY 2011. See INS, Ann. Rep. Cong., Unaccompanied Juveniles in INS Custody (2001).

[7] Sarah Herman Peck & Ben Harrington, The “Flores Settlement” and Alien Families Apprehended at the U.S. Border: Frequently Asked Questions, Cong. Rsch. Serv., R45297, 5 (2018).

[8] Office of Refugee Resettlement, About the Program (Apr. 29, 2021), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/ucs/about [https://perma.cc/AY8R-KMGN].

[9] Camilo Montoya-Galvez, U.S. Adding 16,000 Emergency Beds for Record-High Number of Migrant Children Entering Border Custody, CBS News (Mar. 25, 2021, 7:16 PM), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/immigration-migrant-children-emergency-beds-border-crisis/ [https://perma.cc/GZ6A-JDJS].

[10] Office of Refugee Resettlement, supra note 8.

[11] In March 2021, HHS announced it opened nine new intake sites and influx facilities to “temporarily house unaccompanied migrant children.” Lauren Giella, Nine New Migrant Shelters Have Opened Since Biden Took Office, Newsweek (Mar. 24, 2021, 12:20 PM), https://www.newsweek.com/five-new-migrants-shelters-have-opened-since-biden-took-office-1578253 [https://perma.cc/A9QN-EUSB].

[12] Reno v. Flores, 507 U.S. 292, 298 (1993).

[13] Stipulated Settlement Agreement at 8–9, Flores v. Reno, No. CV 85-4544-RJK(Px) (Jan. 17, 1997), https://www.aila.org/File/Related/14111359b.pdf [https://perma.cc/XA9E-F3H6].

[14] Id. at 5.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Influx Facilities for Unaccompanied Immigrant Children: Why They’re Needed & How They Can Be Improved, Justice for Immigrants (last visited Apr. 14, 2021), https://justiceforimmigrants.org/what-we-are-working-on/unaccompanied-children/influx-facilities-for-unaccompanied-immigrant-children-why-theyre-needed-how-they-can-be-improved/ [https://perma.cc/9RFH-YEL7].

[19] Office of Refugee Resettlement, Ann. Rep. to Cong. FY 2018, at 47–52 (2018).

[20] Id.

[21] I spent hours digging through ORR and CBP archives for such statistical evidence and found no specific data to report.

[22] U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., Unaccompanied Alien Children Shelter at Homestead Job Corps Site, Homestead, Florida, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Unaccompanied-Alien-Children-Sheltered-at-Homestead.pdf [https://perma.cc/96TF-KEJ5].

[23] Id.

[24] Justice for Immigrants, supra note 19.

[25] Further, some children are subjected to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse within emergency shelters, where these events are underreported and as such, underregulated. See Dara Lind, “No Good Choices”: HHS Is Cutting Safety Corners to Move Migrant Kids Out of Overcrowded Facilities, ProPublica (Apr. 1, 2021, 8:00 AM), https://www.propublica.org/article/no-good-choices-hhs-is-cutting-safety-corners-to-move-migrant-kids-out-of-overcrowded-facilities [https://perma.cc/J2G8-KZEN]; Cynthia Pompa, Immigrant Kids Keep Dying in CBP Detention Centers, and DHS Won’t Take Accountability, ACLU (June 24, 2019, 12:45 PM), https://www.aclu.org/blog/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/immigrant-kids-keep-dying-cbp-detention [https://perma.cc/TX2C-3WMF].

[26] Nat’l Inst. of Health, WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32191675/ [https://perma.cc/W244-8QX5].

[27] FY 2020 Nationwide Enforcement Encounters: Title 8 Enforcement Actions and Title 42 Expulsions, U.S. Customs and Border Prot. (Nov. 20, 2020), https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/title-8-and-title-42-statistics-fy2020 [https://perma.cc/RDU2-HTCS].

[28] Justice for Immigrants, FAQ: On the Partial U.S./Mexico Border Closing Due to COVID-19, https://justiceforimmigrants.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/FAQ-Border-Closure.pdf [https://perma.cc/P7BT-LPQE].

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] Morgan Sandhu, Unprecedented Expulsion of Immigrants at the Southern Border: The Title 42 Process, Harvard Law (Dec. 26, 2020), https://covidseries.law.harvard.edu/unprecedented-expulsion-of-immigrants-at-the-southern-border-the-title-42-process/ [https://perma.cc/BL9Y-F8KF].

[32] 42 U.S.C.A. § 265 (West).

[33] Notice of Order Under Sections 362 and 365 of the Public Health Service Act Suspending Introduction of Certain Persons From Countries Where a Communicable Disease Exists, 85 Fed. Reg. 17060-02 (Mar. 26, 2020).

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] For more information on anti-immigrant rhetoric: See Susan Ferriss, Rhetoric Attacking Immigrants Has Been on Constant Boil for Years, Center for Public Integrity (Aug. 7, 2019), https://publicintegrity.org/inequality-poverty-opportunity/immigration/immigration-decoded/immigrant-rhetoric-history/ [https://perma.cc/9YV6-YD4D].

[37] Notice of Order Under Sections 362 and 365 of the Public Health Service Act, supra note 34.

[38] A Guide to Title 42 Expulsions at the Border, American Immigration Council (Oct. 15, 2021), https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/guide-title-42-expulsions-border [https://perma.cc/WKD9-EQ5G].

[39] Laura Finley and Luigi Esposito, The Immigrant as Bogeyman: Examining Donald Trump and the Right’s Anti-Immigrant, Anti-PC Rhetoric, 44 Human. & Soc’y 178, 5-6 (2019).

[40] The principle of non-refoulement prohibits States from removing individuals to their home countries when there are existing substantial grounds to believe that these persons would be at risk of serious harms upon their return. See UN Off. of the High Comm’r for Hum. Rts., The Principle of Non-Refoulement Under International Human Rights Law, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Migration/GlobalCompactMigration/ThePrincipleNon-RefoulementUnderInternationalHumanRightsLaw.pdf [https://perma.cc/JU5Y-23MZ].

[41] Dara Lind, COVID-19 CAPIO, https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6824221-COVID-19-CAPIO.html [https://perma.cc/93DL-NFDK].

[42] “Thus, to effectuate the 1980 Refugee Act’s mandate for an asylum procedure, as well as U.S. treaty obligations and maxims of fundamental fairness, the [Third Circuit] held that the INS process had to provide ‘the most basic of due process.’” Kendall Coffey, The Due Process Right to Seek Asylum in the United States: The Immigration Dilemma and Constitutional Controversy, 19 Yale L. & Pol’y Rev. 303, 322–23 (citing Marincas v. Lewis, 92 F.3d 195, 203 (3rd Cir.1996)); see also Augustin v. Sava, 735 F.2d 32 (2nd Cir. 1984) (holding that the right to request asylum ensured a limited due process right); see also Selgeka v. Carroll, 184 F.3d 337 (4th Cir. 1999) (holding that an asylum applicant is entitled to the minimum procedures of due process).

[43] Q&A: US Title 42 Policy to Expel Migrants at the Border, Hum. Rts. Watch (Apr. 8, 2021, 4:15 PM), https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/08/qa-us-title-42-policy-expel-migrants-border [https://perma.cc/72VU-QASG].

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] Corky Siemaszko, 9-Year-Old Girl Drowns While Trying to Cross Rio Grande, CBS News (Mar. 26, 2021, 1:01 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/9-year-old-girl-drowns-while-trying-cross-rio-grande-n1262174 [https://perma.cc/CRY6-P7HY].

[47] U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., Facts and Data (Dec. 20, 2021), https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/about/ucs/facts-and-data [https://perma.cc/S34L-AQTF].

[48] District Court Blocks Trump Administration’s Illegal Border Expulsions, ACLU (Nov. 18, 2020), https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/district-court-blocks-trump-administrations-illegal-border-expulsions [https://perma.cc/F5J3-PTD5].

[49] U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., supra note 48.

[50] Hum. Rts. Watch, supra note 44.

[51] Jeff Abbott, US Accused of Using COVID as Excuse to Deny Children Their Right to Asylum, Guardian (Nov. 10, 2020, 6:00 AM), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/nov/10/us-child-deportations-guatemala-pandemic [https://perma.cc/24U4-NJ4R].

[52] See Flores v. Barr, No. CV854544DMGAGRX, 2020 WL 5491445, at *12 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 4, 2020) (over 75% of minors stayed in hotels for three days or more); id. at 17 ([COVID-19] “is no excuse for DHS to skirt the fundamental humanitarian protections that the Flores Agreement guarantees for minors in their custody, especially when there is no persuasive evidence that hoteling is safer than licensed facilities”); A Guide to Title 42 Expulsions at the Border, American Immigration Council (Oct. 15, 2021), https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/guide-title-42-expulsions-border [https://perma.cc/WKD9-EQ5G].

[53] Flores v. Barr, WL 5491445, at *11.

[54] Am. Immigr. Council, supra note 39.

[55] AAP Statement on Media Reports of Immigrant Children Being Detained in Hotels, Am. Acad. of Pediatrics (July 23, 2020), https://services.aap.org/en/news-room/news-releases/aap/2020/aap-statement-on-media-reports-of-immigrant-children-being-detained-in-hotels/ [https://perma.cc/DKK7-4G2R].

[56] Caitlin Dickerson, 10 Years Old, Tearful and Confused After a Sudden Deportation, N.Y. Times (Oct. 21, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/20/us/coronavirus-migrant-children-unaccompanied-minors.html?campaign_id=9&emc=edit_nn_20200520&instance_id=18629&nl=the-morning®i_id=77906208&segment_id=28532&te=1&user_id=7e35169c1b6ab60525ecf19d800d0417 [https://perma.cc/M3DH-KFV2].

[57] Id.

[58] Id.

[59] On June 26, 2020, Judge Dolly M. Gee (United States District Court for the Central District of California) ordered Dr. Paul Wise and Independent Monitor Andrea Ordin to monitor the care of minors at family residential centers and make recommendations for remedial action that they deem “appropriate.” After their initial interim report (on July 22, 2020), the Court further ordered (on July 25, 2020) that Ms. Ordin should request further information regarding safe and sanitary conditions “and/or [the government’s] continuous efforts” to provide these conditions. On August 7, 2020, the Court issued its final order, requesting for Dr. Wise and Ms. Ordin look directly into the “hoteling issue.” Notice of Filing an Interim Report on the Use of Temporary Housing for Minors and Families under Title 42, Flores v. Barr, No. CV 85-4544-DMG (AGRx) (Aug. 26, 2020), https://www.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.cacd.45170/gov.uscourts.cacd.45170.938.0.pdf [https://perma.cc/9XXN-SRNJ].

[60] Id.

[61] P.J.E.S. v. Wolf—Defending Due Process Rights for Children Seeking Refuge in U.S. During COVID-19 Pandemic, ACLU of D.C., https://www.acludc.org/en/cases/pjes-v-wolf-defending-due-process-rights-children-seeking-refuge-us-during-covid19-pandemic [https://perma.cc/3LH4-Q8MF].

[62] The attorneys and law firms representing Flores Class Members (unaccompanied minors) include: Legal Advocates for Children and Youth, La Raza Centro Legal, Inc., Latham and Watkins, and UC Davis Immigration Law Clinic, among others. See Flores v. Barr, 2020 WL 5491445.

[63] Id. at 1.

[64] Id. at 2.

[65] Id. at 7.

[66] Id.

[67] Id.

[68] Id. at *8

[69] Id.

[70] Id.

[71] Id.

[72] Id.

[73] Id.

[74] Id. at *10.

[75] Id.

[76] Id. at 10.

[77] Id.

[78] P.J.E.S. by and through Escobar Francisco v. Wolf, 502 F. Supp. 3d 492, 518 (D.D.C. 2020).

[79] Id. at 548.

[80] Id. at 551.

[81] Rates of migrant kidnappings are rapidly increasing in Mexico, as organized crime groups take advantage of their vulnerability to force them into sex and drug trafficking. See Molly O’Toole, ‘Sitting Ducks for Organized Crime’: How Biden Border Policy Fuels Migrant Kidnapping, Extortion, L.A. Times (Apr. 28, 2021, 6:00 AM), https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2021-04-28/biden-title-42-policy-fueling-kidnappings-of-migrant-families-at-border-and-extortion-of-u-s-relatives [https://perma.cc/7LNK-4RAD]; see also Ryan Devereaux, New Report Documents Nearly 500 Cases of Violence Against Asylum-Seekers Expelled by Biden, Intercept (Apr. 21, 2021, 2:36 PM), https://theintercept.com/2021/04/21/asylum-seekers-violence-biden-title-42/ [https://perma.cc/JQ8V-X4RA].

[82] U.S. Government Confirms Migrant Children Experienced Severe Mental Health Issues Following Family Separation, Physicians for Hum. Rts. (Sept. 4, 2019), https://phr.org/news/u-s-government-confirms-migrant-children-experienced-severe-mental-health-issues-following-family-separation/ [https://perma.cc/3KQT-HSB6].

[83] Id.

[84] CPB Announces March 2021 Operational Update, CPB (Apr. 8, 2021), https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/cbp-announces-march-2021-operational-update [https://perma.cc/H7B4-ERQJ].

[85] Nick Miroff, Border Crossings Leveling Off But Remain Near 20-Year High, Preliminary April Data Shows, Washington Post (Apr. 23, 2021, 4:44 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/mexico-border-crossings-april/2021/04/23/31206e82-a459-11eb-8a6d-f1b55f463112_story.html [https://perma.cc/HE82-KL66].

[86] Camilo Montoya-Galvez, supra note 9.

[87] Sabrina Rodriguez, Biden Blocked from Expelling Migrant Families Using Title 42, Politico (Sept. 16, 2021, 3:30 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/16/biden-title-42-blocked-asylum-512271 [https://perma.cc/AD5B-GPXN].

[88] Jack Herrera, Biden Brings Back Family Separation—This Time in Mexico, Politico (Mar. 30, 2021, 1:33 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2021/03/20/border-family-separation-mexico-biden-477309 [https://perma.cc/6SCN-LWFZ].

[89] ICE Guidance on COVID-19, U.S. Customs and Border Prot. (Mar. 1, 2022), https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus [https://perma.cc/BZL6-WYLJ].

[90] For current rates of infection across the United States, please view: Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest Map and Case Count, N.Y. Times (Mar. 13, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html [https://perma.cc/3VMK-ET5M].

[91] Jack Herrera, supra note 89.

[92] Divya Manoharan & Hope Frye, Biden Must End Mandatory Expulsion on the Border, Foreign Policy (May 14, 2021, 1:30 PM), https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/05/14/biden-title-42-immigration-border-covid/ [https://perma.cc/TF3P-WMQG].

[93] John Marcus, ICE Wasted Millions on Unused Detention Space, Independent (Feb. 15, 2021, 10:32 AM), https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/ice-detention-private-prisons-contracts-b1802246.html [https://perma.cc/LE7G-S7F4].

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.