Introduction

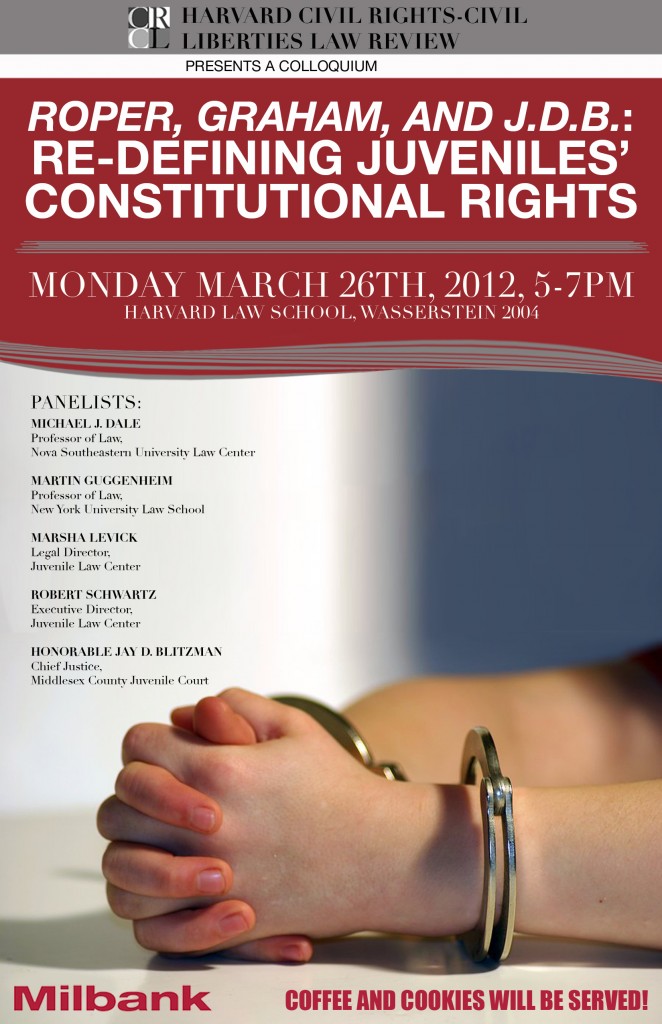

On Monday, March 26, 2012, the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, in conjunction with the Juvenile Law Center and the Milbank Foundation, presented a colloquium: Roper, Graham, and J.D.B.: Redefining Juveniles’ Constitutional Rights. Guests at the event included Martin Guggenheim of NYU Law School, Marsha Levick and Robert Schwartz of the Juvenile Law Center, Michael Dale, of the Nova Southeastern Law Center, and the Hon. Jay Blitzman, chief judge of the Middlesex County Juvenile Court.

The colloquium discussed three upcoming articles that will be published in Volume 47, Issue 2 of the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. Those articles are “Graham v. Florida and a Juvenile’s Right to Age Appropriate Sentencing” by Martin Guggenheim, “The United States Supreme Court Adopts a Reasonable Juvenile Standard in J.D.B. v. North Carolina for Purposes of the Miranda Custody Analysis: Can a More Reasoned Justice System for Juveniles Be Far Behind?” by Marsha Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney, and “The Legal Significance of Adolescent Development on the Right to Counsel: Establishing the Constitutional Right to Counsel for Teens in Child Welfare Matters and Assuring a Meaningful Right to Counsel in Delinquency Matters” by Jennifer Pokempner, Riya Saha Shah, Mark Houldin, Michael Dale and Robert Schwartz.

Pre-publication drafts of each of the articles can be accessed by clicking on the articles’ titles above. Video from the event is available here. Responses to the articles will be posted below as they are received.

Responses

Josh Tepfer

Josh Tepfer joined the Bluhm Legal Clinic as a Visiting Clinical Professor in 2008. He co-teaches a clinical course with the Center on Wrongful Convictions. He is also the Principal Investigator for a pilot project — The Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth. Prior to joining Northwestern, Josh worked as a public defender with the Illinois State Appellate Defender’s office in Chicago for four years.

Marsha L. Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney’s article in the upcoming edition of CRCL persuasively argues that the Supreme Court’s decision in J.D.B. v. North Carolina holding that a child’s age must inform the custody analysis is a seminal moment for the juvenile justice reform movement. This is a position shared by New York University Law Professors Martin Guggenheim and Randy Hertz in their recent piece in the Washington University Journal of Law & Policy, which calls J.D.B. “a watershed moment in the jurisprudence of juvenile rights.” From this perspective, there is nothing but vertical nods of agreement. J.D.B. takes the “kids are different” jurisprudence in the recent Eighth Amendment cases like Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida and applies it to a wholly different constitutional provision. With this, the Supreme Court has understood that kids are kids no matter the criminal stage or the constitutional moment.

Levick and Tierney’s article explores the possible implications of J.D.B.’s “reasonable juvenile standard” in other arenas of criminal law, focusing on criminal responsibility for the act committed. Of course, J.D.B. is a Fifth Amendment self-incrimination case, so, as the authors acknowledge in footnote 118, the implications on this area of the law are more direct. In their piece, Guggenheim and Hertz explore this issue, ultimately concluding that a nonwaivable right to confer with counsel prior to a police interrogation is the only adequate safeguard to protect children’s rights during custodial interrogation.

Once again, there is nothing but vertical nods from this writer. But as Guggenheim and Hertz acknowledge, such a rule “imagines a world quite different from ours.” Until we reach this world, with J.D.B. as our guide, there are some more modest criminal procedure reforms that can happen for juveniles in the interrogation room. Consider one possible example.

Forty-three years ago, in Frazier v. Cupp, the Supreme Court held a police interrogator’s misrepresentation to a “mature” suspect “of normal intelligence” that another individual had confessed and implicated the suspect “was insufficient . . . to make this otherwise voluntary confession inadmissible.” This and other cases have led some courts and the leading interrogation training firm of Reid & Associates to bless the practice of lying about evidence to the suspect or using trickery and deceipt. But even Reid stops short when it comes to juveniles: in Chapter 15, page 352 of the most recent Fifth Edition of Criminal Interrogation and Confessions, the authors state explicitly that the technique of “introducing fictitious evidence during an interrogation . . . should be avoided when interrogating a youthful suspect with low social maturity.”

The Seventh Circuit recently considered the practice of lying about evidence to a suspect during an interrogation. In Aleman v. Village of Hanover Park, a civil case, the court considered whether the police’s deception rendered the suspects later false admission involuntary. The suspect therein was being investigated when a baby died in his care; during the investigation, the interrogator told the suspect that the doctors had excluded any other possibility other than the baby dying of shaken baby syndrome while in his care. Judge Posner’s unanimous opinion held that this lie took away Aleman’s “rational choice” of whether to confess: “Aleman had no rational basis, given his ignorance of medical science, to deny that he had to have been the cause.”

Aleman could be read as only denouncing lies to suspects about medical evidence or evidence requiring specialized training. J.D.B.’s stated specific concern about juveniles in the interrogation room, however, highlights why there are reasons to think that a juvenile suspect’s “rational choice” as to whether to confess could be taken away with seemingly lesser lies. As I have written about previously, in J.D.B., all nine current Supreme Court justices accepted the premise that juveniles are uniquely vulnerable to the pressures of custodial interrogation.

So what lies during an interrogation might be impermissibly coercive with juvenile suspects while acceptable with adults? A lie about the results of a polygraph exam might be one example. Several courts, like People v. Mays (citing cases), admitted inculpatory statements made following a police ruse that falsely indicates to a suspect that he failed a polygraph exam. The Mays court determined that only false evidence ploys that are likely to elicit a false confession are inadmissible, and a lie about a polygraph does not qualify.

We can debate the Mays holding and the other cases as it applies to all suspects, but the debate is picked up a notch when it comes to juveniles. I occasionally speak to children and teenagers about wrongful convictions and false confessions. One suggestion to prevent wrongful convictions I’ve gotten often from these young men and women is to give the suspect a lie detector test, and then we will know if they really did it. When I got this suggestion most recently, I asked the class of thirty eighth graders how many of them thought that this was a good suggestion; every hand went up. I followed up by asking if any of them knew that police were allowed to lie to them when they were questioned about an offense, and not a single one of them knew that. Of course, none of the students knew that the results of a polygraph exam were generally not allowed to be considered at a trial.

While my little survey is far from scientific, it does suggest that falsely telling a young suspect that he failed a polygraph exam may take away his “rational choice” to confess or make it likely to elicit a false confession. Indeed, it must be extremely counterintuitive to a child to even hear that police are legally permitted to lie to them when questioned, as children generally are told to trust police and go to them when they are in trouble. While an adult or seasoned criminal might understand this, children will not. These factors show cause to revisit the seemingly settled interrogation law allowing lies to suspects through a juvenile lens. As Roper, Graham, and now J.D.B. teach us, what might be okay for adults, may not be right for kids.

Erik Pitchal

Erik has had a varied career in and around the law, as a trial attorney, scholar, and teacher, with most of his work focused on advocacy for children and their families and helping agencies develop policies to better protect and serve them. He has represented children in juvenile court cases; litigated federal class action civil rights cases; managed a university-based policy institute; and created a law school clinical education program. He writes, lectures, and appears on television as an expert commentator on current legal issues.He currently serves as an independent consultant to schools, universities, camps, and other child-serving organizations, offering risk management, policy development, program evaluation, training, and related services. Erik is a graduate of Yale Law School and Brown University and was named Child Advocate of the Year by the American Bar Association.

When I was a new attorney at the Legal Aid Society’s Juvenile Rights Practice, charged with representing children in the dependency system, one of the strongest messages we received in training was to always have a position on the ultimate question in our cases and to advocate on subsidiary questions accordingly. For example, in New York (as in most states), dependency proceedings are bifurcated, with an initial adjudication on the merits of the petition, and a subsequent dispositional hearing (assuming that the court makes a finding of abuse or neglect) to determine what should happen to the kids. Legal Aid lawyers were taught then (and still are now) that their position on disposition should drive their advocacy on fact finding. Thus, for example, if you are trying to get your clients returned home as quickly as possible, you should seek dismissal of the petition at the adjudication phase (assuming there is no way to settle the issue with the agency). The law provides two bites at the apple – why not take both?

I take this approach for granted. It seems so obvious – it is what every lawyer does in every type of case. A defendant in a tort case wants to minimize the amount of damages he has to pay; his lawyer thus tries to get the case dismissed on the law, dismissed on summary judgment, dismissed after the plaintiff’s evidence for failure to establish a prima facie case, and so on. Why should it be different in dependency law? So I was really taken aback when, teaching this approach in some advocacy trainings I conducted for dependency attorneys in the Midwest last summer, I encountered a tremendous amount of resistance. “How could you, as the child’s lawyer, argue against a finding of neglect if the mother really did neglect her?” was the typical objection.

Comments like this one reveal an essential truth about dependency law: in a system designed to protect children, well-intentioned people are frequently prepared to sacrifice other important values, including legal rights, on the altar of child protection. To the lawyers I met last summer, the idea that an attorney might facilitate a court’s making the “wrong” decision on a fact question was repulsive, especially if it would put a child at risk. Just because your client wants to go home does not make getting a case dismissed a “success,” they would say. Quite the opposite: in their view, a child’s lawyer should only argue for family reunification at the proper time – that is to say, after a finding is made, so that any return home is under the watchful eye of continued CPS monitoring.

Reading the terrific Pokempner et al. article made me think of these objections in part because the authors are (like me) so grounded in the norm of rights. However, I am afraid that the Mathews argument the authors make (and that I have made too) cuts the other way and unwittingly supports the views of the lawyers I described above. The article asserts that “counsel in child welfare matters is integral to arriving at accurate fact-finding.” In the context of the adjudication phase of a dependency case, your everyday children’s lawyer would agree with this statement – and proceed to help the agency make its case, regardless of the client’s position on custody. On this view, what I am calling the Legal Aid approach is in tension with the Pokempner assertion: a Legal Aid lawyer’s primary duty is to the client, not to helping the court get to the “right” result. For example, poking holes in the agency’s case at trial just because your client wants to go home does not actually help the court reach a more accurate decision about whether neglect occurred – in fact, such advocacy contributes to the risk that the court will make an erroneous decision, the very opposite of the Mathews argument for the right to counsel. And so the “right” to a lawyer in the traditional sense – in the Legal Aid model – has the potential of undermining child safety. Many child advocates do not like this, as I experienced dodging rotten tomatoes last summer.

This observation reveals an enduring schizophrenia in juvenile law as a field and among children’s lawyers as a profession. When it comes to children in the delinquency and criminal justice systems, most advocates can get on board the rights revolution and endorse an approach along the lines of what the Juvenile Law Center (and others) have been brilliantly and successfully arguing in the last several years: “Children are different, and thus deserving of more rights to protect them against the state’s punitive purposes.” When the state is seeking to punish, rather than protect, a child, safe harbor is found in a strong rights orientation. But when it comes to children in the dependency system – where the state is seen as a protective and benign (if somewhat bungling and imperfect) force – rights are seen by many as an impediment to safety. Or, at the very least, safety is the paramount right, trumping all others.

The value of reaching an “accurate outcome” in a judicial proceeding is a good touchstone for analyzing this phenomenon. In a delinquency case, we are willing to give up accuracy if it conflicts with fundamental rights. (Or, put another way, the concept of “accuracy” is elastic and goes beyond correct discernment of “what happened” to also include protection of the defendant’s rights.) Thus, even if a child “did it,” he is still entitled to a Mapp hearing, hearings to suppress statements and identifications (if the requisite facts are proffered or established), and effective assistance of counsel (including during plea bargaining), just like an adult.

But in a child protection case, if the parent “did it,” does the child actually have any cognizable legal interest in the adjudication of that ultimate fact? To be sure, the child has fundamental liberty interests at stake. A useful question to consider is whether counsel can protect those rights just as well after the adjudication as before. Unlike the delinquency proceeding, where the child’s established rights are designed to protect against the offense of an adjudication – regardless of whether the allegations in the petition are true or not – the rights of the child in a dependency case do not rise or fall with the adjudication of the allegations made against the parent. Those of us who spend time thinking and theorizing about children’s rights probably would do well to spend more time examining the adjudicatory phase of dependency cases to see if rights and protection can be better harmonized in that context.

Of course, for a long time rights and aid were seen as mutually exclusive norms in the delinquency system, with pendulum swings between the two in our national policy. The early American system beget the turn-of-the-20th-century Juvenile Court movement, which beget Gault, which led (some say) to treating children like adults all over again. Some, like retired Judge Michael Corriero of New York, tried to re-insert benevolence into the system for handling serious juvenile offenders – perhaps at the risk of rights. “Children are different” can be used by the state to protect them in a way that undermines their status as rights holders just as much as “children are different” can be used to grant them rights in the first place. What the Juvenile Law Center has been able to do, I think, is successfully argue that children’s differences entitle them to both rights and protection.

As the authors correctly point out, Gault was never meant to replace the rehabilitative model with the pure adult model. Children can be treated differently – better, in fact – than adults, and still be afforded due process, which is not an exclusively adult benefit in our system. (The Court could have grounded Gault in the enumerated provisions of the Constitution, but instead relied on the Due Process Clause.) When a child is confronted by the power of the state which seeks to detain him, rights are the protection.

Similarly, in the dependency context, rights and protection can co-exist. Children can have the especial benefit of a regime dedicated to protecting their safety, but this need not come at the expense of their putative status as rights-bearers. However, under the current, dominant approach to child protection in the United States, rights and protection are seen as either-or-propositions. Many can agree that when children’s lack of capacity exposes them to overreaching by the state – as in J.D.B. – then children should have the benefit of due process protections. But when the proceeding is designed to protect the child – when the state is seen as a protective force, not a threatening force – a rift is exposed in the child advocacy community.

The best illustration of this may be Camreta v. Greene, a Ninth Circuit decision that was later vacated by the Supreme Court. I’ve written about Camreta elsewhere, but in brief, it involved a § 1983 claim for damages by a nine-year-old girl against a CPS investigator and a deputy sheriff. CPS had a tip that the girl was being sexually abused by her father, and rather than asking her mother for permission to interview her (or seeking a court order), the defendants went to her school, pulled her out of class, and questioned her for over two hours. The legal question was whether her Fourth Amendment rights had been violated. Many child advocates asserted that the child did not need or deserve Fourth Amendment rights; they claimed that she was being protected by the state, from her father. They said that giving her constitutional rights in that circumstance would have done the opposite of protecting her. More than 25 amicus briefs were filed, with many child advocates favoring the plaintiff and many others siding with the defendants. The National Association of Counsel for Children’s listserv became a forum for discussing the case, since authors of briefs on both sides were NACC members. Listserv chatter was quite harsh and, at times, personal. Those who favored reversal seemed particularly incredulous that anyone who calls himself a child advocate could favor a legal rule elevating children’s rights above protection, accusing plaintiff’s counsel of essentially exposing children to serious risk of abuse with his arguments.

The Supreme Court vacated the Ninth Circuit opinion on Munsingwear grounds – there was a complex intersection between the Pearson problem in qualified immunity jurisprudence and mootness as to the plaintiff that is well beyond the scope of this comment. (I have blogged about it elsewhere.) So the uncertainty in the law around the aspect of CPS investigations present in Camreta will continue, and with it, the debate about which is more important in dependency law, children’s rights or child protection.

The major tensions in juvenile law today concern the relative power, rights, threats, and duties of the state as versus parents. Where the effect of Gault is still felt, and where the Juvenile Law Center’s excellent advocacy using new brain science to establish that children are different has been most effective, is in the Court’s rejection of any self-appointed benevolent role by the state in the arrest and prosecution of children. In that context, at least, the Court is quick to see that children deserve special rights as protection against the state. Thus, in J.D.B., the threat was the state and the constitutional right was protection against that threat. But in Camreta, many argued that the father was the threat, the state was protection, and the asserted constitutional right would have undermined that protection. When does the state turn from threat into protector? When does a parent change from protector into threat? The only salient difference between the facts of Camreta and J.D.B. that I can discern is that in Camreta, the state claimed that it was playing a protective role, and in J.D.B. it acknowledged that it was not.

Interestingly, in another children’s rights case from last term, Entertainment Merchants, the Court rejected the state’s role as an aide to parents seeking to protect their children from danger (in the form of violent video games). The Court was not willing to apply the “children are different” trope to protect children when the First Amendment was at issue. Instead, it seemed prepared to let parents manage the aftermath when their kids imbibe too much in the Mortal Kombat-riddled marketplace of ideas. The protection argument failed in the face of rights.

Going forward, the trick will be getting the Court to continue to use “children are different” only in circumstances in which it will enhance their rights, as occurred in J.D.B., Roper, and Graham, and not in situations that undermine their rights (usually in the name of protection), as could have occurred in Camreta. In Entertainment Merchants parents were not seen as the force from which children need protecting. When it comes to dependency, where the worry is that parents are dangerous and the state is offered as a protective force, advocates should expect that the Court will still prepared to credit the state’s benevolent purposes, possibly to the detriment of children’s rights.

Barbara Fedders

Barbara Fedders is a clinical assistant professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law, where she co-directs the Juvenile Justice Clinic. She was formerly a clinical instructor at the Harvard Law School Criminal Justice Institute and a public defender in Roxbury, Massachusetts. She has published several articles on juvenile justice and child welfare issues.

In “The United States Supreme Court Adopts a Reasonable Juvenile Standard in J.D.B. v. North Carolina for Purposes of the Miranda Custody Analysis: Can A More Reasoned Justice System for Juveniles be Far Behind?” Marsha L. Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney present a compelling case that J.D.B. v. North Carolina might well alter key criminal law doctrines as they apply to young people. After briefly commenting on their compelling analysis, I offer some thoughts on how the case can spur advocacy that is aimed at keeping young people out of the juvenile and criminal systems in the first instance.

J.D.B. builds from Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida, in which the Supreme Court banned, respectively, the juvenile death penalty and life without parole sentences for juvenile non-homicide crimes. J.D.B. extends the logic of those cases – that kids are different in constitutionally significant ways – beyond the Eight Amendment framework and into the police interrogation context. The case holds that a young person’s age must be considered in analyzing whether she was in custody. Levick and Tierney argue that it could and should prompt courts and legislatures to re-calibrate the doctrines of felony murder, negligent homicide, provocation, justified force, and duress to account for the age of a juvenile.

Their analysis seems particularly prescient in light of Miller v. Alabama, this term’s Supreme Court decision banning mandatory sentences of life without parole in juvenile homicide cases. Writing for the majority, Justice Kagan explains that these sentences unconstitutionally pretermit consideration of a juvenile’s “immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences.” Adopting some of the themes contained within Levick and Tierneys’ piece, Justice Breyer, joined by Justice Sotomayor in concurrence, opines that a sentence of life without parole ought never to be imposed upon a juvenile convicted of murder via the felony-murder doctrine. “[T]the theory of transferring a defendant’s intent is premised on the idea that one engaged in a dangerous felony should understand the risk that the victim of the felony could be killed, even by a confederate… Yet the ability to consider the full consequences of a course of action and to adjust one’s conduct accordingly is precisely what we know juveniles lack capacity to do effectively,” he writes. Might Miller open the door to further legal challenges to harsh punishments of juveniles, including statutes requiring mandatory transfer of juveniles to adult criminal court? Justice Roberts, in dissent, seems to think so: “There is no clear reason that principle would not bar all mandatory sentences for juveniles, or any juvenile sentence as harsh as what a similarly situated adult would receive.”

Welcome though they are for youth and their advocates, Roper, Graham, J.D.B. and Miller address owhat happens to youth already ensnared within the juvenile and criminal systems. J.D.B. might also prompt us to work at a grass-roots level to prevent so many youth from being arrested and prosecuted in the first place. Consider the case’s facts. Local police officers came to J.D.B.’s middle school to investigate an off-campus, non-violent crime. School officials made no attempt to contact J.D.B.’s grandmother, his legal guardian, before permitting him to be questioned by police. Instead, a school resource officer hauled him – a thirteen-year-old, seventh grader receiving special education services – out of class and into a conference room for questioning. After at least thirty minutes of interrogation, in which officers made a series of threats and promises – without first giving the warnings required by Miranda or the North Carolina statute mandating that youth under age fourteen must be informed that they may have a parent or guardian present during questioning – J.D.B. confessed.

Additional legislative and policy changes needed, beyond those worked by J.D.B., are needed in at least three areas. First, much of the research underlying the holdings in Roper, Graham, J.D.B. and Miller regarding the fundamental differences between youth and adults supports a modification in the warnings that are administered to young people. As psychologists have noted, youth are particularly inclined to make choices indicating a propensity to comply with authority figures during police interrogations. Younger adolescents are especially unlikely to grasp the meaning of the Miranda warnings. Doubly so when the youth has learning disabilities, as in J.D.B. Thus, I agree with those who have urged legislatures or police departments to require officers to use language that is understandable to a child, and to mandate that officers ensure juveniles’ understanding of each of the rights contained in the Miranda warnings.

Second, even if youth are given warnings in language they can intellectually process, they may be developmentally ill equipped to be able to assert their rights. Rarely if ever having experienced themselves as rights-bearing subjects, most young people cannot be expected to assert the right to remain silent. The power imbalance between an armed police officer and a child is simply too great. Thus, I join those advocates and scholars (including Randy Hertz and Marty Guggenheim as well as Joshua Tepfer on this blog) who believe in the necessity of a bright-line rule mandating that no child under the age of eighteen may be questioned without first having conferred with counsel.

Third, school boards and legislatures must create policies and laws that both limit the authority and discretion of police officers in schools – if they won’t do away with school police officers entirely – and ensure students’ constitutional rights are protected. As in J.D.B., schools around the country funnel vulnerable young people – particularly youth from low-wealth communities, youth of color, and youth with disabilities – into the juvenile and criminal systems, abdicating their educational responsibility. Multiple civil rights organizations have decried the school-to-prison pipeline that dominates so many low-wealth communities around the country.

The facts of J.D.B. were somewhat unusual in that J.D.B. was interrogated by off-campus police regarding an off-campus crime; more typical are the frequent searches, seizures and interrogations that occur on campus by on-campus school resource officers. SROs receive minimal training and oversight, and in nearly all jurisdictions can conduct searches and seizures based only on reasonable suspicion rather than probable cause. Even when courts find school searches unconstitutional, the fruits of the search will likely be used as evidence against a student in a suspension hearing, as schools do not typically apply the exclusionary rule to suspension proceedings. What’s more, as Jason Langberg, Drew Kukorowski, and I noted in an earlier report, studies suggest that a heavy SRO presence in schools intimidates students, creates an adversarial environment, and results in excessive and unwarranted referrals to the juvenile and criminal systems.

What, specifically, should change regarding criminalization of students? Just as a start: state courts should follow the lead of a recent case decided by the Washington Supreme Court holding that a school police officer needed probable cause to conduct a warrantless search of a high school student’s backpack. Breaking from the trend of state courts that have lumped school police officers in with teachers and administrators in evaluating the propriety of school searches, the Washington court properly recognized that school police officers have constitutionally significant, different functions from school officials. Principals maintain order and discipline in school; police discover and prevent crime. As a result, the Court correctly reasoned, police officers in schools are subject to the probable-cause requirement when conducting searches.

Legislatures and school administrators should amend punitive policies for truancy and school misbehavior. For example, earlier this year, the Los Angeles City Council voted unanimously to amend a portion of the municipal code that provided for punitive ticketing of youth for tardiness and truancy from school. The amendment to the code provides for students to be directed to counseling and remediation resources, and/or to complete community service rather than being ticketed, fined or handcuffed. In Clayton County, Georgia, and Jefferson County, Alabama, juvenile court judges Steven Teske and Brian Huff have developed proposals for graduated consequences for school-based offenses designed to decrease the numbers of juvenile court referrals from school systems. Once adopted, these proposals have resulted in dramatic reductions in minor school offenses in juvenile courts. Rather than referrals to juvenile court, school-based misbehavior (at least for the first and sometimes second offenses) warrants alternative sanctions such as formal warnings and workshops. In Wake County, North Carolina, a school system beset by one of the nation’s largest long-term suspension rates, advocates successfully lobbied for changes to the student code of conduct that provide for suspensions of shorter duration.

There is much left to be done to achieve Levick and Tierney’s hoped-for, more reasonable system for young people. Yet J.D.B. – and the grass-roots advocacy it might inspire – should give us hope that we might accomplish it.