[pullquote]“Those whom we would banish from society or from the human community itself often speak in too faint a voice to be heard above society’s demand for punishment. It is the particular role of courts to hear these voices, for the Constitution declares that the majoritarian chorus may not alone dictate the conditions of social life. The Court thus fulfills, rather than disrupts, the scheme of separation of powers by closely scrutinizing the imposition of the death penalty, for no decision of a society is more deserving of ‘sober second thought.’”

McCleskey v. Kemp, 481 U.S. 279, 343 (1987) (Brennan, J., dissenting)

[/pullquote]

In 1987, petitioner Warren McCleskey, a black man sentenced to death in Georgia, presented to the Supreme Court powerful evidence of systematic racial discrimination in the application of capital punishment.[1] McCleskey’s key ammunition? The “Baldus study,”[2] an empirically impeccable examination of the death penalty as applied in Georgia. The study determined that defendants in Georgia who killed white victims were over four times as likely to receive the death penalty than defendants who killed black victims; moreover, black defendants eligible for the death penalty were significantly more likely to be sentenced to death when compared with white defendants. McCleskey, a black man who killed a white police officer, stood no chance.

In the face of this empirical evidence, however, the majority in McCleskey turned a blind eye to the clearly systematic racism affecting the criminal justice system. According to the majority, these glaring statistics were not a problem under either the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (based on a lack of purposeful discrimination in his specific case) or the Eighth Amendment (because Georgia’s sentencing standards fell within the precedent-determined “permissible range of discretion”). Powerful dissents[3] in McCleskey by Justice Brennan and Justice Blackmun truly deserve their own post.

Close to three decades have passed since McCleskey. How have claims of racial discrimination in the criminal justice system fared?

During the October 2015 term, the Court will hear the case of Foster v. Chatman.[4] Foster is not a direct comparison to McCleskey, but rather broadcasts that in 2015, racial biases not only still exist in our criminal justice system but rather permeate every crevice of discretion. Where McCleskey dealt with jury sentencing, Foster deals with racial prejudice by prosecutors at the jury selection stage.

Foster presents an extraordinary set of facts.[5] The prosecutor in eighteen year-old Timothy Tyrone Foster’s capital trial used peremptory strikes to keep all four prospective black jurors out of the jury box. Foster was black, and his victim was an elderly white woman. The defense, anticipating this move by the prosecution, filed a Batson objection, available to a party when it believes the opposing party used a peremptory strike to exclude a juror on the basis of race, ethnicity, or sex.[6] But for each of the four black jurors, the prosecutor presented between eight and twelve non-racial reasons (most of which were patently inaccurate or pretextual) for striking each of these jurors.

Normally, this would be the end of the Batson objection for a defendant like Foster.

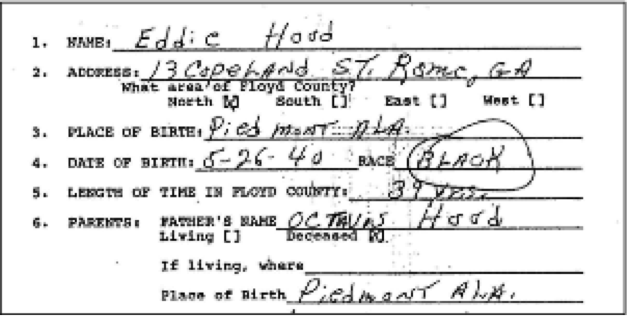

But in 2006, Foster’s habeas counsel procured[7] the “smoking gun”: the prosecution’s jury selection notes from the capital trial. The notes are rife with references to the black prospective jurors’ race. For example:

- Each black juror’s name highlighted in green, with a corresponding key in the upper right hand corner.[8]

- The word “black” circled on each juror questionnaire.

- Three of the prospective black jurors labeled as B#1, B#2, and B#3.

It is impossible to deny the racism at work in this case. Yet the case arrives at the Supreme Court because the Georgia Supreme Court determined that Foster failed to demonstrate purposeful discrimination.[9]

Foster counts among his supporters a group of prosecutors who filed an amicus brief in the case, arguing that the prosecution in Foster’s trial clearly violated the Batson rule. But the behavior doesn’t seem to surprise the authors of the brief; they submit that “[s]ome prosecutors have even provided trainings that encourage racial discrimination and explain how to conceal improper motivation from the courts.”[10] Too often prosecutors are able to discriminate under the guise of facially neutral reasons.

Where McCleskey proffered an indictment of the entire capital punishment sentencing regime, Foster comes forward with just the facts of his case—once in a lifetime damning facts. Facts that might persuade even the most willfully “colorblind” justices that the prosecutor in this case violated the Constitution, even if they are not (yet) willing to indict the entire system.

[1] McCleskey v. Kemp: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/481/279/case.html

[2] http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6378&context=jclc

[3] https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/481/279/case.html

[4] http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/foster-v-humphrey/

[5] Available in full in petitioner’s brief: http://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2015/08/14-8349-ts.pdf

[6] https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/476/79

[7] Procured by way of the Georgia Open Records Act

[8] Pictures are courtesy of petitioner’s brief (public documents under the Georgia Open Records Act)

[9] http://sblog.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2015/05/2015.01.30-Foster-Appendix-to-Cert-Petition1.pdf

[10] http://www.scotusblog.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2015/08/14-8349_20tsac_20Joseph_20diGenova.pdf