Photo credit: Getty Images.

Months before his death, Thurgood Marshall warned about apathy in the interminable American pursuit of forming a more perfect union. The Supreme Court justice was born into Jim Crow and built his career upon making racial segregation, discrimination, and injustice accountable to the Constitution. As he accepted the Liberty Medal in 1992, Marshall cautioned against the instinct to “play ostrich”—to complacently keep our heads in the sand. Marshall urged Americans to recall what was in the ambition of what can be, not to dwell on the past but to gain inspiration for the future. His advice remains particularly relevant today, as Americans find ourselves at another crossroads. Although this national reckoning about race is painful to many, it represents a pivotal moment—an opportunity to modernize our comprehension of what was and what can be to meet the civil rights challenges of this generation.

While today’s reckoning was catalyzed by the high-profile deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery, the sadness and anger reflected in recent events was in the making for a long time. Frustration over systemic unfairness, delayed justice, and frequent disregard for Black life is not new. Moreover, these conditions pervade not only the justice system but many areas of life, including health care, employment, housing, voting rights, representation, and education. Nevertheless, the justice system presents a stark illustration. In 2018, Black people comprised only 12% of the population but accounted for 33% of the sentenced prison population. Still today, some people reduce this extreme discrepancy to a story of personal irresponsibility and poor choices amid colorblind enforcement and prosecution in a post-racial America. But the tides are changing. Recent protests and shifts in public opinion indicate that the durability of this lazy narrative is waning, as recognition builds of the many ways that racial inequality manifests both explicitly and implicitly.

One way that racial inequality manifests is through drug arrests. Notwithstanding the fact that drug usage rates are similar across races, and drug users generally buy drugs from people of the same race, Black people constitute more than one in four drug arrests. A 2020 report found that Black people are arrested at higher rates than White people for marijuana possession in every state. Despite comparable usage rates, African-Americans are 3.64 times more likely to be arrested for possession. Drug arrests go hand-in-hand with stop-and frisk. In the case of New York City, 80% of these stops resulted with young Black and Latino men not being arrested or summoned. The most commonly reported reasons for a stop were “fits a relevant description” at 43.1% and “furtive movement” at 18%, both of which are subject to unconscious bias. These stops have consequences. Of the over 1,000 unarmed people who died from “police harm” between 2013 and 2019, about one-third were Black, and 17% of the Black deceased were unarmed, a larger share than other racial groups and 1.3 times greater than the average of 13%.

Data derived from New York City stop-and-frisks show that four of every five reported stops between 2014 and 2017 were of Latino and Black people. Dramatic discrepancies like these also exist in other major cities, which were figurative battlegrounds in the War on Drugs. The government-led War on Drugs campaign, notable for its racialized drug criminalization, exacerbated the development of mass incarceration. A former architect of destructive War on Drugs-era policies later admitted that they were intentionally structured upon pernicious racial motivations.

In addition to arrests, racial inequality manifests through sentencing. When convicted, Black men receive, on average, 19.1% longer sentences than White men for the same crime. The U.S. Sentencing Commission noted that violence in an offender’s criminal history does not appear to account for sentencing differences, as Black men received sentences 20.4% longer than White men with similarly violent pasts. This discrepancy is paralleled in disciplinary infractions for children—Black students are nearly four times as likely to be suspended than White students and face harsher punishment for the same offense.

Moreover, Black people are more often victims of wrongful arrests and convictions. According to analysis from the University of Michigan Law School, African-Americans constituted 47% of exonerations listed in the National Registry of Exonerations as of October 2016. The analysis found that Black convicts are more likely to be innocent than their White counterparts convicted of major crimes like murder and sexual assault.

As gripping as these examples are, they signify only part of the enduring racial injustices that have brought Americans to this consequential precipice. The filming of fatal events, such as the Floyd and Arbery cases, has offered one agent for change. Videos that capture fatal encounters have enabled the public to view incidents with their own eyes rather than chiefly relying on accounts of individuals who are directly involved and have a stake in the interpretation of events. Beyond videos, amplified exposure of disturbing cases through news reports and academic scholarship have made these problems not just hard to ignore, but difficult to dismiss as isolated incidents that lack a linking nexus. While every instance has unique characteristics, they frequently involve commonalities—the escalation from a minor incident to a deadly one, excessive force or brutality when the person is apprehended, treating a person with preconceived notions of guilt rather than presumption of innocence, the state of being unarmed, a lack of transparency or urgency when investigating cases, inconsistencies between official reports and filmed footage, and, perhaps most disturbingly, loss of life when the deceased was engaged in an everyday activity.

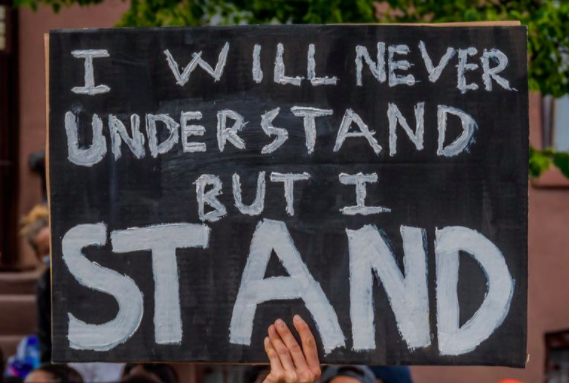

The accumulation of these situations has brought public opinion to rapid shifts, notably in the perceptions White individuals have about racism and discrimination. 52% of White voters now believe that they have a better chance of getting ahead than Black people. The percentage is the highest reported since the poll asked in 1997. When asked about policing, 52% of White voters now say that Black people face racial discrimination in the use of force. These upswings are reflected in the broadening consciousness that the infamous cases involving Floyd, Taylor, and others like Philando Castille, Jordan Davis, Botham Jean, Laquan McDonald, Walter Scott, and Tamir Rice are not unrelated occurrences. These deaths are at last being seen for what they are—installments within a saga of deferred or denied accountability for errors and misjudgments that unnecessarily cost civilians their lives.

Months after Eric Garner died in 2014 after being put in an illegal chokehold, only 43% said they saw underlying problems in the handling of his death. Weeks after Floyd’s death, 74% of Americans think the killing signals an underlying problem with racial injustice. The recognition of the pain that so many Black people experience is bittersweet. While a hard-fought culture war victory, it reflects the tragic reality that acknowledgment of this anguish was culture war fodder at all. We live in a world where a 12-year-old playing in a park with a toy gun was shot within two seconds, but mass murderers who target children, synagogues, and churchgoers are apprehended alive to have their day in court. These double standards are finally being viewed with heightened public scrutiny. More Americans have come to question the system that allowed 16-year old Kalief Browder to rot in Rikers for three years over a minor theft case that never went to trial while 19-year-old Brock Turner was sentenced to six months in jail for felony sexual assault, which carries a maximum sentence of 14 years. Turner eventually served three months of his light sentence. Browder, who was never found guilty of a crime, committed suicide after his release from Rikers, where the teen endured nearly two years of solitary confinement during his three-year imprisonment.

One finding represents a critical opportunity for policy change to address racial inequity—85% of voters say that race relations will be extremely, very, or moderately important in deciding which presidential candidate to support. This fresh sense of urgency for action has compelled Congress and presidential candidates to pursue tangible policy action. It comes as local, state, and federal government officials have rapidly pursued reforms in the past month. From Kentucky to Iowa, Minnesota to Kansas, New York to Washington, D.C., legislatures have introduced, amended, or passed over 159 bills and resolutions pertaining to policing. These pieces of legislation include a variety of solutions, many comprehensive rather than piecemeal, in addressing racial injustice and policing reform. Among these ideas are the reexamination of qualified immunity, reassessment of union practices, and a shift from punitive enforcement to an emphasis on rehabilitation and community-oriented action. While these efforts are only the beginning, they are an encouraging start if momentum can be maintained. America’s 2020 national reckoning is a victory against the destructive urge to “play ostrich” and an opportunity for a patriotic revitalization of what can be to ensure that every American can share in a more perfect, just, and domestically tranquil union.

Christina Coleburn is an incoming J.D. candidate at Harvard Law School.