While most people are familiar with criminal forfeiture––a practice that allows the government to confiscate your property if it proves the property was used in the commission of a crime for which you were indicted––its more formidable and much more often used counterpart, civil asset forfeiture, is frequently forgotten in public discourse. Unlike criminal forfeiture, civil asset forfeiture allows state and local enforcement officials to seize your property because they merely suspect your property was used in connection with a crime. This practice implicates grave concerns regarding civil liberties, but a staggering 72% of Americans have no idea it even exists.

In criminal forfeiture, the owner of the property the government is taking is afforded all of their rights under the Constitution. This means that the defendant must be appointed an attorney if they cannot afford one and the government must prove their guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. But in civil asset forfeiture, the person whose property is taken has no rights under the Constitution. This is because the charges are brought against the property and not the person, which results in peculiar case names like United States v. One Book Called Ulysses by James Joyce[1] and United States v. 2,507 Live Canary Winged Parakeets.[2] In these cases, law enforcement officials need only show by a preponderance of the evidence (more likely than not) that your property has or could be used in a crime. And if you challenge the seizure, the burden is reversed: your property is guilty until you prove it innocent.

In essence, civil forfeiture laws turn government officials into bullies, shaking you down for your lunch money. Except the bullies are backed by the power of the state; they come with warrants, uniforms, and loaded weapons, and they often pocket much more than lunch money.

The use of civil asset forfeiture surged at the start of the drug war, after President Reagan ratified the Comprehensive Crime Control Act in 1984. The Act allowed law enforcement, for the first time, to keep the proceeds seized from anyone suspected of a drug crime as a way to subvert drug trafficking. Subsequently, states passed laws that were ostensibly intended to take money and property from drug kingpins in an effort to disrupt their distribution structures. But in practice, the overwhelming majority of seized assets are coming from the poor. The average amount seized is $800, and in some places like Chicago, cops have taken as little as 34 cents. Because it often costs much more to litigate than the stolen property is worth, victims are left with no recourse. The Washington Post found that “only a sixth of [the 60,000 cash seizures examined]” had been legally challenged; but in over 40% of the cases that were, “the government agreed to return money” after an appeals process that averaged over a year.

Justice Thomas highlighted the disparate impact civil asset forfeiture has on minorities in a recent dissenting opinion, stating that “this system—where police can seize property with limited judicial oversight and retain it for their own use—has led to egregious and well-chronicled abuses,” and it “target[s] the poor and other groups least able to defend their interests in forfeiture proceedings.”[3]

Civil forfeiture operations usually begin with the stop of a motorist on the pretense of a minor traffic violation, allowing police officers to shroud their true intention to search the car for large sums of cash. Imagine this scenario: an officer pulls you over for failure to signal and then asks if you have any large amounts of cash in your car. Because you are afraid the officer might think something is up and you know the money is legally yours, you say no. He then asks if he can search your car. Out of what is likely an amalgam of fear, intimidation and an unawareness that you can say no, you oblige. He then proceeds to find the $200,000 you were traveling with to buy a house,[4] or the $90,000 you recently won playing poker[5], or the $8,500 you planned on using to buy a car. Then––based on nothing more than a hunch that your cash is linked to criminal activity––he takes it.

Unfortunately, motorists are not the only ones at risk of encountering this scenario. Officials may seize your entire life savings in an airport,[6] or steal $100,000 from your bank account because they suspect you deposited money in a way that avoided bank reporting requirements.[7]

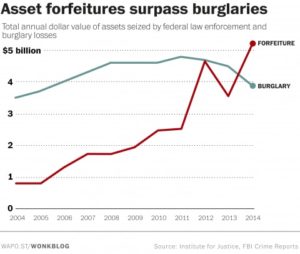

For decades, police have requisitioned money and property unrelated to criminality without serious judicial oversight and used it to fund their departments. According to the Institute for Justice––a cadre of people dedicated to eradicating civil asset forfeiture––the lucrative revenue stream created by the practice grew to $4.5 billion in 2014, resulting in more money taken from American citizens by law enforcement officers than all burglaries combined. And since department funding comes from the seizures, state and local police departments have a highly perverse incentive to continue the activity.

Police can often recover most or all of the money they seize, and they can spend the cash with nearly unbridled discretion. For example, one department used seizure funds to buy a $600 coffee maker, another used $250 for tickets to see CeeLo Green, and many departments use the funding on seminars and training programs––through companies like Desert Snow––that teach officers how to make traffic stops even more profitable.

Civil asset forfeiture can also distort law enforcement objectives. In a recent judiciary committee hearing, Darpana Sheth––senior attorney with the Institute for Justice––described a Tennessee report from just last year that found police officers ignored the eastbound lanes on a local highway where drugs usually flow in, and instead surveilled the westbound lanes where drug money often flows out. “Police are really focusing, not on trying to get the drugs, not on trying to enforce the drug laws and stop that flow throughout the country. They’re focused on getting the money.”

States have responded to bipartisan opposition of the practice by leading the charge for reform. More than 20 states have passed some form of civil asset forfeiture reform and New Mexico, North Carolina, and Nebraska have completely abolished the practice. However, even in abolitionist states, police departments still regularly illegally seize civil assets. Law enforcement can also always bypass the limits of their own jurisdictions under “adoptive forfeiture,” also known as “equitable sharing,” an ironic euphemism given the parity implied by the name. Under adoptive forfeiture, state or local law enforcement can keep 80% of the proceeds from forfeited property if they chose to file the case under federal law rather than state law, thus allowing the federal government to “adopt” the property first. Even in states where civil forfeiture is legal under state law, opting to file the case under federal law first––rather than state law––can often be more lucrative because some state laws include profit-reducing restrictions on seizures.

During the Obama administration, former Attorney General Eric Holder limited adoptive forfeiture by prohibiting state and local authorities from submitting seized assets to federal agencies for adoption unless the property was directly related to public safety concerns––such as firearms and explosives––or the property was seized by state or local authorities in connection to a federal investigation.

But recently, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reinstated adoption so that states can once again use this federal government loophole without limitation. As Leon Neyfakh, staff writer at Slate, explained: either Sessions “can’t fathom that police departments would ever target innocent people for financial gain, or he just doesn’t care.” President Trump also exhibited a callow understanding of civil forfeiture when, in an advisory meeting, he casually proclaimed “we’re gonna go back on [civil forfeiture],” reasoning “How simple can anything be?”

In an attempt to assuage the inevitable abuses of adoption, Jeff Sessions’ policy increases oversight and training, and implements automatic review by a federal prosecutor of any forfeiture under $10,000. But, as ACLU lawyer Kanya Bennett put it, because “[w]e can’t trust the very law enforcement agencies that stand to profit from a forfeiture to police themselves,” such safeguards are likely futile.

Luckily, Congress is fighting back. In September, the House adopted amendments that would defund the newly restored equitable sharing program, compelling state and local police enforcement officers to play by the rules set by their own legislature. And two pieces of reform legislation are currently pending in committee.

After disappearing in committee last year, the DUE PROCESS (Deterring Undue Enforcement by Protecting Rights Of Citizens from Excessive Searches and Seizures) Act of 2017 may finally make it to the floor, and Senator Rand Paul reintroduced the FAIR (Fifth Amendment Integrity Restoration) Act earlier this year. Both pieces of legislation shift the burden of proof from the property owner to the government, raise the standard of proof in civil forfeiture proceedings from “preponderance of the evidence” to “clear and convincing,” and demand states provide legal representation for indigent owners in civil forfeiture proceedings. The FAIR Act may be somewhat more transformative because it would also abolish the equitable sharing program and require any portion of proceeds given to the federal government in connection with civil forfeiture to go to the Treasury Department rather than the Department of Justice.

Of course, reform legislation is promising. But it remains to be seen whether the amendments or the Acts will be enacted, and none address the most inimical abuses of civil forfeiture: those permitted under state law.

The Constitution is clear: property shall not be seized without due process. But rather than swiftly eradicating civil asset forfeiture altogether, this administration continues to give law enforcement officials more flexibility in the plundering of American property.

[1] 72 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1934).

[2] 689 F. Supp. 1106 (S.D. Fla. 1988).

[3] Leonard v. Texas, 137 S. Ct. 847, 848 (2017).

[4] Id.

[5] Davis v. Simmons, 100 F. Supp. 3d 723, 727 (S.D. Iowa 2015).

[6] United States v. $11,000 U.S. Currency, 2013 WL 5890635, at *1 (M.D. Tenn. Nov. 1, 2013).

[7] United States v. $107,702.66 in United States Currency Seized from Lumbee Guar. Bank Account No. 82002495, 2016 WL 413093 (E.D.N.C. Feb. 2, 2016).