Responsible Resource Development: A Strategic Plan to Consider Social and Cultural Impacts of Tribal Extractive Industry Development

Carla F. Fredericks, Kate Finn, Erica Gajda, and Jesse Heibel*

Click here for a PDF of the entire paper.

Abstract

This paper presents a strategic, solution-based plan as a companion to our recent article published in the Harvard Journal of Law and Gender, “Responsible Resource Development.”[1] As a second phase of our work to combat the issues of human trafficking and attendant drug abuse on the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation (MHA Nation), we developed a strategic plan to better understand the time, scale, and capacity necessary to address the rising social problems accompanying the boom of oil and gas development there. During our process, we discovered, through multiple engagements with tribes, that similar negative impacts of rapid economic development are occurring throughout the United States. In particular, many tribes are deeply concerned about the rapid increase in human trafficking on and near their reservations coincident with the entrance or re-entrance of the extractive industries.

The paper is a generalized strategic plan for tribes and other stakeholders to consider in combating the social impacts of extractive industry development. Although the plan is designed to be universal in scope and aspires to assist tribes throughout the country, it does not purport to take into account the unique complexities of individual Indian communities. The history, values, and research are examined to develop a process that will best suit a Native approach to each of the solutions presented, informed foremost by our relationship with the tribal community on Fort Berthold, as well as other tribes nationally. A cornerstone of the plan is that services that center on cultural identity and draw upon family connections are a preferred approach for Native peoples. Further, any approach to trafficking of Native women and children must take account of the colonial genesis of trafficking, generational trauma, and other risk factors.

Introduction

This paper presents a strategic, solution-based plan as a companion to the recent article published in the Harvard Journal of Law and Gender, “Responsible Resource Development.”[2] As a second phase of our work to combat the issues of human trafficking and attendant drug abuse on the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation (MHA Nation), we developed a strategic plan to better understand the time, scale, and capacity necessary to address the rising social problems accompanying the boom of oil and gas development there. During our process, we discovered, through multiple engagements with tribes, that similar negative impacts of rapid economic development are occurring throughout the United States. In particular, many tribes are deeply concerned about the rapid increase in human trafficking on and near their reservations coincident with the entrance or re-entrance of the extractive industries.

What follows is a generalized strategic plan for tribes and other stakeholders to consider in combating the social impacts of extractive industry development. Although the plan is designed to be universal in scope and aspires to assist tribes throughout the country, it does not purport to take into account the unique complexities of individual Indian communities. The history, values, and research are examined to develop a process that will best suit a Native approach to each of the solutions presented, informed foremost by our relationship with the tribal community on Fort Berthold, as well as other tribes nationally. A cornerstone of the plan is that services that center on cultural identity and draw upon family connections are a preferred approach for Native peoples. Further, any approach to trafficking of Native women and children must take account of the colonial genesis of trafficking, generational trauma, and other risk factors.

This plan has many mutually reinforcing sections and recommendations; however, it serves purely as a foundation for further discussion and planning on the part of tribes. Differing tribes come to the table with different resources and capacities, as well as different relationships with local, state, and federal partners. This strategic plan aims to provide a roadmap for tribes facing extractive industry development to consider the social and cultural impacts of development in an individual and self-determined fashion that will maximize benefits of development for their own community.

Development Impacts

This strategic plan grew out of deep concern that the negative impacts of oil and gas development were tearing the social fabric of reservation Native communities.[3] In particular, tribal communities in the Bakken were increasingly concerned about the increase in human trafficking coincident with the rapid oil development occurring there. While economic development has brought incredible economic opportunity for many, it has also meant an increase in violent crime, drug abuse, and sex trafficking of Native women and children. Unfortunately, the rapid pace of oil and gas development taxes and ultimately overwhelms the existing law enforcement and social services infrastructure on many reservations.

Our research confirmed that the influx of temporary oil workers in “man camps” near the Fort Berthold reservation, alongside a lack of law enforcement capability to provide safety under the new conditions, created an environment rife for trafficking abuse. One report noted a 75% increase in reports of sexual assaults of Native Women on the Fort Berthold reservation.[4]

The intersectional nature of trafficking and drug abuse requires a multi-faceted approach that is driven by legal and structural solutions. Sex trafficking and drug abuse are interconnected. Traffickers often seek out those victims that are perceived to be the most vulnerable due to one or more of these risk factors: age (minors), poverty, homelessness, chemical dependency, prior history of abuse, and lack of support systems.[5] Traffickers then control victims with tactics such as sexual, emotional, or mental abuse; controlling victims through drug use and addiction; withholding money for travel or access to help; or by threats of violence.[6] Drug addiction and sexual assault often occur simultaneously and have devastating long-term effects for the individual, their family, and the community. Because the effects of drug addiction and sexual violence will impact the communities at MHA for generations to come, this paper is meant to provide insight and research to name the issues and to develop a long-term and holistic response. Because trafficking occurs in the shadows, and the path to healing is long and uneven to victims fallen to drug addiction, this plan takes a comprehensive view of the resources necessary to ensure healthy Native communities.

The paper addresses several distinct issues: (1) promoting victim centered and trauma informed approaches to victim services; (2) increasing vital access to culturally appropriate drug treatment services and facilities; and (3) building up the existing criminal justice system to provide safety for all individuals in reservation communities. Finally, we recommend strategies for engaging with corporations to create awareness about the impacts of development on and near Native communities and to advocate for corporate social responsibility initiatives inclusive of Native rights.

This strategic plan is a beginning. The recommendations in this paper suggest some of the ways to catalyze action, and they all invite creativity in implementation. Because oil and gas development is predicted to continue for many years, now is the time to address these issues to ensure the stability and growth of healthy and vital Native communities.

Methodology

In order to fully explore this issue, we have endeavored to engage with as many stakeholders as possible. Our goal has always been to better understand the needs of victims, families, and service providers on reservations and create a relevant plan of action to begin facing these difficult social issues.

It is important to note that there is still relatively little data related to human trafficking of Native women and children. Reports, such as Garden of Truth[7] and Maze of Injustice,[8] provide good information on the distinct nature of violence against Native women and children. The May 2016 National Institute of Justice Report on Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native Women and Men begins to fill in statistics about anecdotal reports of violence in Indian Country.[9] Much of our academic research is encompassed in our white paper published in February 2015, Responsible Resource Development and Prevention of Sex Trafficking: Safeguarding Native Women and Children on the Fort Berthold Reservation.[10] But the detail necessary to create this plan is based largely on in-person and telephonic interviews with stakeholders.

Throughout the plan, we build on nationally recognized promising practices by tailoring them to the particular economic, cultural and social context of reservation communities. We have included information from federal sources, as well as grassroots organizations dedicated to meeting the needs of Native individuals. We have given particular weight to organizations that integrate a tribal perspective in their service delivery.

This strategic plan will take time to organize and implement. However, at each step, our hope is that Native reservation communities will feel increasingly more supported by the infrastructure being built around them.

To ensure a common understanding and approach to combating human trafficking, this strategic plan relies on several definitions adopted in the Federal Strategic Action Plan on Services for Victims of Human Trafficking in the United States.[11]

First, we use the terms “victim” and “survivor” interchangeably in this report. As stated in the Federal Human Trafficking Strategic Report:

The term “victim” has legal implications within the criminal justice process and generally means an individual who suffered harm as a result of criminal conduct. Federal law enforcement agencies often use the term “victim” as part of their official duties. “Survivor” is a term used by many in the services field to recognize the strength it takes to continue on a journey toward healing in the aftermath of a traumatic experience.[12]

Second, our research also focused on trauma informed and victim centered practices, as defined below:

The victim centered approach seeks to minimize retraumatization associated with the criminal justice process by providing the support of victim advocates and service providers, empowering survivors as engaged participants in the process, and providing survivors an opportunity to play a role in seeing their traffickers brought to justice. In this manner, the victim centered approach plays a critical role in supporting a victim’s rights, dignity, autonomy, and self-determination, while simultaneously advancing the government’s and society’s interest in prosecuting traffickers to condemn and deter this reprehensible crime. . . .

A trauma informed approach includes an understanding of the physical, social, and emotional impact of trauma on the individual, as well as on the professionals who help them. A trauma informed approach includes victim centered practices, as it is implemented with trauma impacted populations. A program, organization, or system that is trauma informed realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for healing; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in staff, clients, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, practices, and settings. Like a victim centered approach, the priority is on the victim’s safety and security and on safeguarding against policies and practices that may inadvertently retraumatize victims.[13]

Multi-Stakeholder Engagement

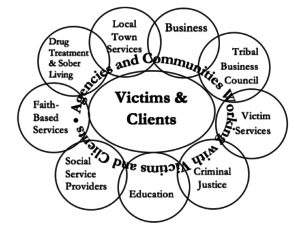

First and foremost, the report recommends forming a taskforce with stakeholders representing all parts of the government – social services, law enforcement, administration, and energy development. Together, stakeholders can provide the multi-disciplinary perspective necessary to combat these issues. When service providers and the government are well connected through the taskforce, they will be able to create a seamless delivery system of culturally appropriate services for victims of human trafficking and families affected by drug abuse. Ultimately the taskforce will be responsible for prioritizing the implementation of this strategic plan.

Goal 1: Create a multi-disciplinary taskforce to promote a comprehensive, coordinated and seamless service delivery system for victims of trafficking and families affected by drug abuse.

The causes and consequences of human trafficking and drug addiction are sometimes intertwined and always complex. There is rarely just one cause of addiction or victimization, or just one service that will provide ultimate health for an individual. Successful service providers often find themselves interfacing with multiple different resources in order to ensure that a client has housing, food, medical care, psychological care, and safety. Thus, a multi-disciplinary approach is necessary to ensure that individuals can be quickly and efficiently connected to the array of resources they need for a healthy recovery.

Forming a multi-disciplinary taskforce creates a web of services for victims and families by better connecting service professionals. The taskforce is not reinventing the wheel, nor creating a special project; rather it provides a systematic point of connection for existing entities to discuss the goals and barriers of their services in real time.

Several interviewees noted that communities already host cross-sectional meetings that occur regularly between various entities to address drug treatment and victim services. At least one interviewee noted that it is difficult to draw people to the existing meetings and that creating time for another such meeting might be challenging. Based on all of the interviews conducted, we found that gaps in communication between service providers continue to hinder access for those seeking vital services. These gaps can be addressed by breaking down existing silos and creating an infrastructure for communication with the goal of creating healthy reservation communities in the short- and long-term.

- Objective 1: Create a collaborative taskforce and hire a full-time staff person for administration.

By definition, a multi-disciplinary taskforce requires participation from the various service providers that assist survivors and those addicted to drugs. In all, this can include social services, medical services, law enforcement,  victim services, psychological services, employment and education assistance, and faith-based services.

victim services, psychological services, employment and education assistance, and faith-based services.

While implementing a taskforce is the best way to ensure systematic connection of service providers, there are several barriers to overcome. First, many organizations already operate with limited staff and financial resources and may not be able to consistently send staff to a regular meeting. Second, providers in many communities are already committed to attend several meetings, such as a Child Protection team meeting and a Sexual Response Team meeting. The proposed taskforce should not duplicate the objectives of other meetings but rather add value for providers already engaged in existing collaborations. To that end, this taskforce can be scheduled to coincide with an existing regular meeting, or an existing meeting can be expanded to encompass these goals.

One model of collaboration, as implemented by VS2000, creates room within the larger structure for participation at varying levels.[14] For example, as implemented in Denver, Colorado through the Denver Victim Services Network, every member of the collaboration meets once per quarter. But several different groups within the larger structure meet as frequently as once per month. The model thus both sustains subject specific collaborations, such as an existing drug treatment task force, but also offers the opportunity to elevate and advertise that group’s work through the system. Doing so may potentially lead to fruitful partnerships and give every network participant a sense of what services exist in the network as a whole.

To ease administration, the Denver Victim Services Network has a dedicated staff person to coordinate all meetings, create targeted agendas for each meeting, and establish a main point of contact for projects within the task force. This model allows for service providers to speak to their expertise at meetings without having to shoulder the administration of the task force. Hiring a dedicated staff person for this reason is integral to the success of this proposed taskforce.

The Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) and the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) offer funding to support coordination of services via a taskforce. The taskforce can then prioritize the different issues to be addressed and seek funding from the same sources to implement the changes. Forming the taskforce will not only allow for discussion around priorities, but it will also provide a foundation upon which to apply for further funding to support the initiatives of the group. Funding this initiative can be granted such that it does not cut against funding for existing programs, as through the Coordinated Tribal Assistance Solicitation (CTAS) that streamlines the U.S. Department of Justice grant-making process. In the future, a permanent funding source for this collaboration could be developed as a part of court fees paid by offenders, or through permanent budget allocations.

- Objective 2: Integrate cross-training during regular meetings to benefit tribal and local service providers.

The driving force behind a collaborative taskforce is a working knowledge of the different resources within the network, as well as a working relationship with the service providers therein. Collaboration by definition is the exchange of information, the altering of activities, the sharing of resources, and the enhancement of the capacity of another for the mutual benefit of all and to achieve a common purpose.[15] Enacting a truly collaborative environment takes time to share information, gain trust, and develop priorities for the group.

One valuable tool to enhance capacity of all stakeholders is to implement a cross-training program. Cross-training is when a partner organization gives a presentation to other partners about their work, their concerns, and their observations. This is one way not only to keep abreast of the types of work being done, and to clarify understanding among partners of the abilities and limitations of the presenting organization. Cross-training can be a useful tool to bridge traditionally difficult relationships and open channels of communication as each entity has the ability to voice its priorities and thus effectuate a clear understanding among all partners.

While many organizations working on reservations have existed for a number of years, and many individuals have multiple contacts at different organizations, what is lacking is a stable structure to exchange ideas and data about the needs of the community. This network structure allows service providers to better understand the role and priorities of their partner organizations and, therefore, to have more realistic expectations of the types of work that each organization can perform in a given situation. A better understanding of each partner organization’s role will help to better address gaps and linkages.

Finally, cross-training can occur organically at monthly or quarterly meetings. It does not have to be a formal presentation, but rather any presentation that allows leaders to elevate their work, reach out for ideas, or update partners on the current status of their resources.

- Objective 3: Implement education and training on related issues for service providers.

The quarterly or monthly meetings can be utilized to provide relevant trainings from partners or outside organizations, depending on the changing needs of the community. For example, a training could be organized that focus on identification of trafficking victims; the efficacy of a needle exchange program in a rural county; the importance of spiritual and cultural wellness initiatives; or even a presentation by high school students about their concerns regarding access to education.

Many of the departments that we spoke with have existing relationships with outside organizations, be they related federal organizations (e.g. the Blue campaign) or subject-specific partnerships (Native American Connections). While these working relationships are a matter of course for the department, partner organizations throughout the network may not be fully aware of these resources and could benefit from knowing that they exist. Different departments could assist the full-time staff person to connect with outside organizations to arrange for these contacts.

Goal 2: Promote a victim centered and trauma informed approach to victim services by creating a connected web of services for victims of violent crime.

Many reservation communities host at least one victim services organization, whether it be dedicated to serving victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, or any and all victimizations that present. Of course, where there is no dedicated service organization, building one is the top priority. The effects of victimization present along many dimensions, be they physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and/or financial. And dedicated victim service organizations can provide access and vital support to victims and survivors along those dimensions, assisting them to regain a foothold when they have experienced debilitating trauma. Additionally, these organizations are able to voice the concerns of victims as an anonymized collective to tribal government, other organizations, the community. Finally, they provide abuse prevention education and awareness to all other community institutions.

It is important for reservation based victim services organizations to maintain a large network of connections to best serve victims. For example, in the case of safe houses, our interview revealed that while on-reservation safe houses may need more beds, many clients feel safer when placed off-reservation in a location that is unknown to the offender. Therefore, relationships with local county and state services are vital to creating a safe environment for healing. Similarly, access to funding through federal sources, such as granting via OVC and OVW is important to build tribal capacity. These sources also provide important access to meetings with state and federal partners to coordinate approaches. Our interviews show that given the complex legal regime applied to Indian reservations (discussed below on page 18), advocates rely heavily on their connections to state and federal resources, in part to focus their attention on ensuring that a victim’s case is brought through the federal system.

Another critical issue to address is access to a trained and qualified Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) on the reservation. Although victims are generally transported to local city centers that could be hours away, interviewees noted that some centers are disfavored due to discrimination. Discussions about hosting a SANE in reservation communities must address capacity as well as training. One particular concern is that heightened privacy and confidentiality requirements when working with sexual assault victims must be adhered to in order to create an environment conducive to reporting. There is fear that office staff not trained in the importance of confidentiality and who live in a close-knit, rural setting may not respect those mandates. Training is thus important not only to establish a baseline of confidentiality requirements, but to assure community members that reporting is a safe and effective option.

- Objective 1: Build personnel capacity for on-reservation victim services organizations.

Staffing at reservation based victim services organizations is of utmost concern. This is not only to ensure that victims receive effective round-the-clock services, but to stabilize organizations that generally suffer from high turnover rates. Additional staffing would give personnel more flexibility and more time for self-care. Staffing at an adequate level would also allow for a dedicated position to be located at the tribal police office to serve victims more quickly and to answer questions and provide support to tribal law enforcement.

The second recommendation is to provide training to an existing staffer, or a new person as resources allow, as a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE). The SANE could be located at the tribal victim services office, or at the local clinic, provided that all staff at the host organization understand and comply with the necessary confidentiality requirements. Training one SANE is a large step forward but should be viewed as one step toward training at least one more person in the next 5 years. Locating a SANE at an easily accessed location on the reservation will ensure (1) that sexual assault and rape victims have access to readily available medical treatment and (2) that treatment is delivered by someone qualified to ensure that evidence is collected to support a future prosecution should the victim choose to pursue a legal case.

Strengthening the relationship between tribal partners is vitally important, even where victim service organizations are well connected to state and federal resources. In part this can be accomplished by increasing capacity to have an advocate at the tribal police station during regular business hours. This goal is also forwarded by ensuring that at least one person participates in the recommended task force to ensure regular communication and provide a victim services perspective to service provision on the reservation.

In short, this recommendation to build staffing will allow victim services organizations to serve more clients, provide more flexibility to existing employees, and develop stronger relationships with tribal partners, thus creating a connected and seamless network of services for victims of crime in Native communities.

Drug Treatment

Goal 3: Increase access to culturally appropriate drug treatment services and facilities.

An individual’s drug abuse increases the likelihood of experiencing sexual assault, domestic violence, and human trafficking.[16] Social conditions like poverty and isolation also play a role in human trafficking, enabling traffickers to “groom” their victims, using incentives like emotional intimacy and promises of financial independence to gain trust, and then using that relationship to engage victims in commercial sex work.[17] Still more concerning is the way that these risk factors can build on one another, with poverty and abuse leading to drug use, or drug use leading to isolation, poverty, and victimization. The prevalence of drug use and addiction on reservations facing rapid economic development has created vulnerable communities leading to the crisis many tribal communities are facing today. The increase in drug use and influx of temporary workers on the reservation has put a strain on the people, the community, and the services offered. In fact, in the case at MHA, 90% of the drug and alcohol related cases are beyond the scope of the local drug treatment center’s services and must be referred to other facilities.[18]

The most promising course of action to protect a tribe’s most vulnerable population is to strengthen its programs to combat drug addiction and dependency. An improved and expanded system allows greater access to treatment for those in need, increased availability of culturally centered treatment, and accessibility of services for drug addicted parents and infants born addicted to drugs.

The following encompasses four major objectives to reach this goal. These objectives are further broken down into immediate and long-term recommendations to better encompass the steps necessary for a tribe to take in the short-term when facing a rapid increase in development and in consideration of the continuing recovery process required to build healthy Native communities.

- Objective 1: Provide sustainable drug treatment services that are culturally tailored and maintain the family connection.

This history of colonization, assimilation, and disease wrought on Native communities has left many Native Americans vulnerable to drug use as a result of the detrimental impacts of historical trauma. Thus, treatment and rehabilitation centers are more successful when they reaffirm tenants of Native identity such as the importance of acting as stewards of the environment and imparting sacred knowledge.[19] The infusion of culture and tradition helps address historical trauma and provides a critical connection to culture and identity for the patient. Also, providing a clean and sober living environment for a mother and child to live in together not only increases the chance of her recovery, but allows the child to bond to the mother and thus reduce the child’s risk of vulnerability in the future, as well as the number of children in foster care. Because the drug epidemic and an attendant increase in the number of children in foster care occur simultaneously, both of these issues must be addressed when creating a comprehensive approach to drug treatment.

While there are important reasons to create access to off-reservation drug treatment facilities, culturally appropriate drug treatment that maintains the family connection located on-reservation is still critical.[20] Drug addiction is a pressing issue to those living on the reservation, as well as to a large number of criminal drug offenders who will return to the reservation and need to successfully re-integrate into the community.[21] One way to accomplish this is to have treatment facilities on the reservation that function as satellite facilities to others in larger cities. In addition to drug treatment facilities, a re-entry, support, and aftercare program to integrate people back into society on the reservation is necessary to sustain healthy lifestyles in the long-term.

Importantly, reservation treatment centers can work to integrate culture and traditional events, activities that hone daily living skills and therapy into drug treatment to encourage “wellbriety.” Wellbriety means to be sober and well and to be aware of the influence of addiction on individuals, families and the community at large. The “well” part of Wellbriety is “the inspiration to go on beyond sobriety and recovery, committing to a life of wellness and healing every day.”[22] However it takes significant resources to offer cultural activities, drug and alcohol evaluations, community based support group meetings, case management and emergency funds.

The strain on infrastructure due to the spike in drug abuse is clear on Fort Berthold and other reservation communities, as existing outpatient, counseling and drug treatment services are unable to meet the needs of an increasing number of people who seek services.[23] Existing services at Fort Berthold struggle to bill for services and to gather enough funding to hire staff because many of the tribal members who require the services are uninsured.[24] Currently the primary health care facility on Fort Berthold uses 90% of the contract health budget for drug-related health care issues.[25] Unfortunately, without further planning, this type of strain may be replicated again in this and other Native communities across the country.

Because the capacity of treatment centers is currently full, this section includes recommendations for the immediate time period, as well as recommendations for building a comprehensive infrastructure of services in the future. Each of the existing programs’ mission can be strategically considered to add up to a larger infrastructure of services that supports community wellness.

Immediate Recommendations

There are several short-term solutions to consider while building the necessary infrastructure for drug treatment centers. First, tribal governments can write tribal laws to “require removing users from their residency when they are causing hardship on others and placing them in rehab centers replete with medial, social and psychological services to begin the healing process.”[26] Although the treatment centers on the reservation may not have the capacity to house those in need, the tribal service centers could continue its current practice of sending those in need to treatment centers off the reservation. This would offer families immediate reprieve and clients immediate assistance. When appropriate on-reservation facilities are built, those in need may be transferred to those treatment facilities.

The first recommendation requires entering into a Memorandum of Understanding with treatment facilities that are successful models of culturally appropriate in-patient drug treatment centers such as Gila River,[27] White Earth,[28] or Native American Connections.[29] Native American Connections and similar centers ensure that healing from drug addiction for Native clients is connected with spiritual and cultural values that will stay with them as they move toward sobriety.[30]

Another recommendation is to temporarily adopt White Bison’s treatment program while gathering information from tribal elders to integrate traditions and culture tailored to the specific tribal community, determining a treatment program that fits that community, and building treatment facilities on the reservation.[31] The White Bison program integrates Medicine Wheel teachings, generally described as a Native method for teaching important concepts about truth and life, that can then be built upon once elders identify more tribal- or clan-based culturally appropriate training and treatment.[32]

A final short- term recommendation is to build capacity at existing locations on the reservation by increasing funding for those programs. Many communities have already laid the groundwork for these vital programs which are beneficial in the short and long-term, and require an infusion of funding to enact programming.

Long-Term Recommendations:

Research supports the need to build a drug treatment facility on the reservation that is culturally appropriate, focuses on maintaining the family connection, and transitions directly into a clean and sober living community. Implementing these types of initiatives will increase access for those in need and improve outcomes for clients and families.

The first long-term recommendation is to develop, plan, fund, and build a high intensity treatment center or provide available space for such treatment of tribal members convicted of meth/drug related offenses, with dedicated space for family interventions. Due to the fierceness and acute addiction of crystal meth and the related effects of addiction, it is important to make a lengthy treatment program available. Research indicates that the initial treatment stay should be at least six months to several years for methamphetamine addiction.[33] Although there are treatment facilities in large cities, the second recommendation is to develop, plan, fund and build facilities to function as satellite facilities in reservation communities.

Next, a dedicated full-time coordinator position should be created to develop a drug program that is culturally appropriate, maintains the family bond, and is tailored to the community’s needs. The Coordinator would gather information about other successful drug treatment programs with similar goals to develop a program that offers a tailored program for all clients, including pregnant women and mothers with infant and/or minor children. The coordinator would not be reinventing the wheel but rather accessing successful models that integrate Native values and culture into drug treatment such as Peaceful Spirit Southern Ute Treatment Program,[34] Gila River, Friendship House Association of American Indians, Inc.,[35] and Native American Connections. The coordinator may also look to successful programs that maintain family connections during treatment such as Haven House,[36] and the New Directions for Families program at Arapahoe House.[37]

An additional recommendation is for the Coordinator to create a council of elders, cultural and traditional leaders to ensure cultural accuracy in integrating culture into drug treatment programs.

The Coordinator could also create a council of elders, cultural and traditional leaders, to ensure cultural accuracy in integrating culture into drug treatment programs.

Although the development of a drug treatment center is critical, it is also necessary to ensure awareness of the disease, the symptoms, and where people can find the necessary resources. Tribes could enlist assistance from drug treatment facilities’ staff to create and distribute culturally appropriate materials on drug use in the community and appropriate steps to take when someone they know is affected.

Finally, tribes should create a clean and sober living community. The existence of a clean community can greatly increase the chance of long-term success of drug treatment.

Any clean community program must include opportunities for families to live together. Consider the Village Families in Transition (FIT) approach.[38] The Village South, Inc., provides “comprehensive substance abuse treatment and prevention services to adults, adolescents, and children.”[39] FIT is federally funded through SAMHSA, and “over a span of 6 months or more…families progress from a period of intense treatment and family reunification to a period of increased independence in which the parents undertake vocational training or employment, accept increased parenting responsibility, and prepare for supported reintegration into the community.”[40] These types of communities are foundational to ensuring healthy Native families in present and future generations.

- Objective 2: Provide training and technical assistance to expand the quality and expertise of drug treatment providers and the effectiveness of drug treatment programs.

The success of drug treatment centers depends on effective management. Tribes should strive to coordinate resources effectively, within the drug treatment center as well as with programs working to combat human trafficking.[41] This requires funding for professional medical services, trained personnel, and infrastructure rendered as a holistic and culturally appropriate intervention.[42] Staff training and education is key to ensuring each component of treatment includes a focus on culture, improves family dynamics, and integrates case management cohesively.

In order to begin developing a culturally appropriate and well-coordinated program, it is first necessary to develop robust management positions. The position of Training Coordinator would provide trainings to gain compliance with standards set for successful drug treatment centers, as well as ensure qualified personnel are employed. This position would create a schedule of trainings for employees; curate workshops and trainings for staff and providers on the reservation specific to drug treatment, trauma, cultural competency, and maintaining the family connection; develop a curriculum to integrate cultural values and instill cultural competency across the entire center; and guarantee training techniques are effective for the specific population by considering whether the trainings are meeting cultural and traditional needs.

The Training Coordinator should be familiar with approaches to training and staff development and include diverse types of trainings such as accessing online modules, bringing in expertise from other Native communities to share success stories, and brainstorming creative approaches to issues that arise. To assist in developing a culturally competent and effective drug treatment program, tribes should consider coordinating and engaging with innovative models of tribal treatment, such as White Bison, Native American Connections, and Gila River, to analyze their training materials and to help build a treatment center model that will be successful for those living in their communities.

Furthermore, an incentive program could attract qualified personnel to the drug treatment centers on the reservation. This could include providing housing benefits and other incentives to create a system of self-care for employees.

- Objective 3: Expand funding opportunities to increase the capacity, infrastructure, and training of drug treatment on the reservation.

As stated earlier, satellite drug treatment centers on reservations would help address several of the vulnerability factors contributing to human trafficking. A drug treatment center on the reservation would allow the patient to have a support group from within the community that they are familiar with and may, as is possible in some residential programs, have access to their children to maintain a strong family bond. Funding a drug treatment center through a 638 contract or compact may help make this option viable and may allow tribes increased flexibility and control of the healthcare programs from IHS.[43] Tribes can either contract with IHS to “deliver health services using pre-existing IHS resources (formula-based shares tables determine funding for various IHS sites), third party reimbursements, [or] grants and other sources.”[44] Several Native-centered facilities, such as Native American Connections, have expertise in building a billing structure that leverages different funding sources to create care options for the short- and long-term. Allowing those that are in drug treatment to have access to their family or to live in the community and have easy access to the satellite center provides opportunity for continuity and connection that addresses the feelings of isolation and shame that many survivors and those struggling with addiction face.

- Objective 4: Increase and support the capacity of tribal family services to provide for the needs of children in foster care.

Not only does drug addiction put those using drugs at risk for trafficking, but it also creates serious risks for their children. Statistics from the Fort Berthold reservation provide a startling example. From January 2013 to August 2015, 132 newborns were born addicted to meth and other drugs.[45] In 2014 alone, 85 babies (three years and younger) were exposed to drugs.[46] This cyclical problem is also visible in the childcare and foster care system on the reservation. By some estimates, 90% of the children in Fort Berthold’s foster care system are placed there, at least in part, because their parents had a drug or alcohol addiction.[47] Those children are removed from their homes to protect them from the clear dangers of drugs and alcohol. But they are removed only to be placed in an overburdened system. The Fort Berthold reservation has close to ninety children in its foster care system, but only twelve licensed foster care homes.[48] Many children can be placed with relatives, but as a result of the shortage of licensed homes others may be placed with families off the reservation.[49]

This system creates serious risks through separation, isolation, and insufficient supervision feeding risk factors that can lead to victimization. Where the rapid pace of extractive industry development occurs, this pattern is bound to be repeated. Because the risks to Native children in foster care have been well documented, they must be taken into account as an additional infrastructure is built to support those children and families in the wake of a drug trafficking and abuse crisis.

In order to help support the foster care system, tribes can develop a school that operates as a full-time replacement of or complement to foster care homes.[50] The Pine Ridge School on the Pine Ridge reservation models this type of complementary approach to more traditional foster programs. The school provides a safe and stable environment for children to live, eat, and attend school, while allowing flexibility for parents who may check children in and out as circumstances determine.

Furthermore, tribes may want to consider the Village FIT approach which strives to foster parental guidance and a sense of belonging. The agency actually shares joint custody of resident children with the state and, in so doing, creates a strong incentive for the mother to retain custody.[51] This approach allows for the drug addicted family member, the child, and others to access necessary resources from one location, thereby increasing the true availability of resources to those most in need.

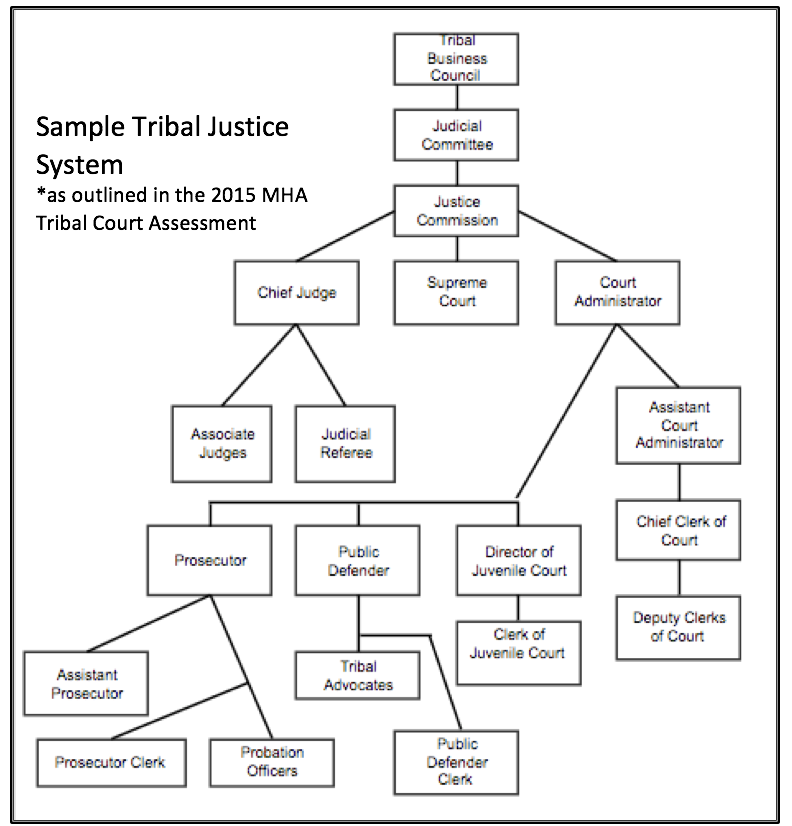

Goal 4: Reform the existing criminal justice system to provide law enforcement and judicial systems that operate independently, efficiently, and professionally to meet the continuing needs of the Tribal Members.

One of the most essential functions of government is to provide for the security and protection of its people. For American Indian tribes, more than a century of United States federal policy has diminished the sovereignty and jurisdiction of tribal governments, limiting their ability to effectively provide justice for wrongs committed within their territory and against their people. This is especially true in the context of criminal law where federal statutes and Supreme Court decisions have collectively worked to curtail the power of tribal justice systems. Nonetheless, tribal court and law reform has gained momentum over the past decades under federal self-determination policies aimed at encouraging tribes to retake control of their governmental structures.[52] Sophisticated tribal justice and court systems are appearing and legal expertise is being developed and applied in many Indian communities. As it stands today, a strong tribal justice system is a critical component of tribal government and a true exercise of sovereignty.

With a growing number of examples, the negative relationship between extractive industries and increased criminality is becoming a common theme in empirical and academic literature. For example, as a result of the rapid exploration and development of the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota, the MHA Nation experienced a dramatic increase in crime on the Fort Berthold Reservation. From 2013 to 2015, the tribe’s court system saw its caseload grow by over 2,000%, with total case numbers in 2015 similar to that of Bismarck North Dakota, which has a population nearly ten times higher than on the reservation.[53] While the specific criminal offenses can vary, a significant number can be attributed to the interrelated social issues of trafficking on the Reservation.

For tribes facing extractive development, it is critical to acknowledge the connection between extractive industry and increased crime, as well as the burden an influx in crime places on the tribes’ existing justice systems. Many tribes are well into the process of making their justice systems more responsive to the broad range of issues arising in Indian country. While these efforts have undoubtedly helped tribal justice systems deal with the challenges they face, the complexity and scale of the issues presented by the operation of extractive industries requires that more be done. Specifically, there are a number of steps that, if taken, will further help tribal justice systems in becoming a more effective tool in combatting the crime, including drug and human trafficking, that resource development brings to reservation communities. The following four objectives were developed through interviews with various tribal leaders and stakeholders and researching federal statutes, tribal court assessments, and various other resources. They aim to identify and address the most pressing issues faced by the tribal justice systems in their efforts to combat the social issues faced by communities near extractive development.

For tribes facing extractive development, it is critical to acknowledge the connection between extractive industry and increased crime, as well as the burden an influx in crime places on the tribes’ existing justice systems. Many tribes are well into the process of making their justice systems more responsive to the broad range of issues arising in Indian country. While these efforts have undoubtedly helped tribal justice systems deal with the challenges they face, the complexity and scale of the issues presented by the operation of extractive industries requires that more be done. Specifically, there are a number of steps that, if taken, will further help tribal justice systems in becoming a more effective tool in combatting the crime, including drug and human trafficking, that resource development brings to reservation communities. The following four objectives were developed through interviews with various tribal leaders and stakeholders and researching federal statutes, tribal court assessments, and various other resources. They aim to identify and address the most pressing issues faced by the tribal justice systems in their efforts to combat the social issues faced by communities near extractive development.

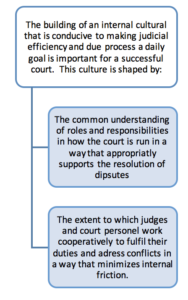

- Objective 1: Build capacity at tribal court systems to ensure the effective resolution of court decisions and sentences.

Judicial Independence and Autonomy

An unfortunate reality of the actualization of tribal sovereignty is the corollary increase in concerns over the accountability and controversy surrounding tribal government. To address these issues, many tribes have made the decision to restructure their governmental institutions to satisfy the needs of the tribe and protect their long-term economic, social, and cultural interests. For some tribes this means amending and updating tribal constitutions, including federally imposed IRA constitutions. For others, it means passing resolutions and developing tribal laws that address the current issues facing their communities. In perhaps all cases, however, it means improving their tribal courts to address civil and criminal matters to the full extent possible under federal law while being seen as providing a fair and impartial judiciary.

Acknowledging the judiciary as a separate and independent branch of government, vesting their tribal courts with the power to review the constitutionality of tribal laws and actions of tribal officials, lengthening judges’ and justices’ terms of office, and prohibiting any decrease in pay during their term are all steps that tribes can take to ensure they are providing a fair and impartial judiciary. While the specific steps adopted by tribal government must be determined by each tribe on an individualized basis, measures like these can help build trust and credibility among tribal members, outside entities looking to do business with the tribe, and state courts who in some circumstances may review tribal court judgments.

Formal Rules of Court Procedure

In addition to a focus on the tribal court’s internal policies and procedures, several interviewees and stakeholders expressed concerns over gaps or inconsistencies in tribal court procedures for use by attorneys and clients. According to stakeholders, these inconsistencies have led to dropped charges and overturned convictions, and must be addressed in order to improve the effectiveness of the tribal court as it deals with the increased pressures brought by the recent spike in criminal cases.

For some tribes, these procedures have been memorialized in separate rules of civil and criminal procedure that govern the appropriate processes for the various actions over which the tribal court has jurisdiction. Rules of appellate procedure can also be helpful in organizing and structuring the appeals process. These rules provide the operating procedures for tribal courts and serve as the backbone for the broader tribal justice system.

The rules of criminal procedure cover a variety of important topics, often including the issuance of a complaint and warrant for arrest, the rights of parties at initial appearances, arraignments, the issuance of search warrants, subpoenas, jury trials, sentencing and judgment, probation, parole, and appeals.[54] One tribe’s rules of criminal procedure had not been updated since it was adopted in the 1970s.[55] For many tribes who have not updated their codes in decades, various developments and changes in other parts of the tribal code have left the rules of criminal procedures inconsistent and outdated. For example, the incorporation of the Federal Rules of Evidence in the Tribal Code conflicted with the Criminal Rules, which provided that the admissibility of evidence and witnesses shall be governed by the trial judge.”

The first step to more fully developing tribal courts’ rules of procedures is to identify gaps and inconsistencies and revise the rules accordingly to ensure that they are current and usable for all parties that appear before the court. This may require the assistance of an outside expert or legal counsel given the already stressed resources of many tribal courts. While current systems may seem operable and sufficient, given the significant consequences that can result from inconsistent or conflicting rules of criminal procedures, this remains an important step in increasing a tribal court’s capacity to properly and fairly deal with the social issues facing the community as a result of increased presence of extractive industries.

Collaboration between Stakeholders

A key component of developing these policies is increased collaboration and information sharing between stakeholders, including the tribal government, judges, court staff, the prosecutor’s office, probation offices, and law enforcement. Developing a comprehensive system for internal information sharing will provide the court with a baseline to ensure that cases before it are efficiently and properly handled from beginning to end. This collaboration is necessary to develop comprehensive solutions and will ensure all issues are addressed, without gaps and inconsistencies.

- Objective 2: Build the capacity necessary to exercise sovereignty in criminal sentencing.

One of the most significant and lasting effects on the administration of justice on reservations of extractive development is the increased pressure on already strained resources, including the tribal court’s physical infrastructure, employee work loads, financial resources, and personnel. This presents numerous hurdles to meeting the increased legal needs of the community. Ensuring that the tribal justice system has the resources and capacity necessary to effectively operate requires steps that will increase the efficiency, reliability, and quality of services to the community.

Facilities

The facilities where tribal justice systems operate play a large part in its overall success and efficiency. Facilities should be centralized and include all aspects of the criminal justice system in order to allow for easier collaboration between parties. Furthermore, facilities should provide the tribal court the physical space and infrastructure necessary to expand the types of services it provides. Most notably, the ability to regularly conduct jury trials will provide the tribe with a necessary step in looking toward increased sentencing authority under VAWA and TLOA. The security of court facilities is also a key component of access to justice because individuals will be reluctant to access court facilities if they do not feel safe. Basic security features such as a bailiff and metal detectors can help make the court, and thus the justice system, more accessible.

Detention facilities can also pose unique problems. How tribal jails are structured can have a significant impact on the success of the system as a whole. Tribes should assess their current resources and determine what steps, if any, should be taken to increase the outcomes of those housed in detention facilities. The services that can increase positive outcomes include counseling, mental health treatment, therapy, health education, and post-release follow-up, among other services. A reconfiguration which more fully connects existing resources is necessary to both addresses increases in violent crime and to prepare for compliance under TLOA and VAWA.

Personnel

An influx of cases means an influx of work, which may necessitate the addition of multiple professional staff positions within the existing court structure. Specifically, a Clerk of Court, prosecution and defense, judges, bailiffs, guardian ad litem, process server, and a Judicial Referee may be required when tribes are addressing these issues.

While positions such as these may be necessary additions, stakeholders have reported that positions like these are hard to fill, either due to lack of resources, retention, or qualified applicants.

Internal Procedures and Policies

As discussed above, a restructuring model to address the influx of criminal cases should look towards increasing its capacity and independence by adding much needed human capital.

Personnel growth does not come without challenges, and the introduction of new positions into an existing and overburdened operating structure is bound to cause issues at any organization. With the influx of new court personnel, many stakeholders have expressed an urgent need for new employees to receive position-specific training. Several noted that the specific issues caused by recent growth include disjointed allocation of tasks and information and the inability to properly train employees due to the immediate need for contribution.[56] Specifically, stakeholders emphasized that new employees would greatly benefit from training on everything from the court’s case-management system to best practices and duties related to their roles within the Court.

Personnel growth does not come without challenges, and the introduction of new positions into an existing and overburdened operating structure is bound to cause issues at any organization. With the influx of new court personnel, many stakeholders have expressed an urgent need for new employees to receive position-specific training. Several noted that the specific issues caused by recent growth include disjointed allocation of tasks and information and the inability to properly train employees due to the immediate need for contribution.[56] Specifically, stakeholders emphasized that new employees would greatly benefit from training on everything from the court’s case-management system to best practices and duties related to their roles within the Court.

Tribal courts should provide position-specific roles and responsibilities training for all court personnel and adopt a policies and procedures manual. This will help increase staff efficiency as well as ensure institutional memory retention. These simple steps would provide a unified approach toward developing a more efficient work place structure with clearly defined roles and duties for court personnel.

Website

In addition to the increased resources for facilities and human capital, tribal courts would greatly benefit from a website that allows litigants and attorneys to access court resources such as the tribal code, the court’s rules of civil and criminal procedure, and other pertinent information such as filing fees or fine schedules. The development of this resource is also a necessary step toward compliance with enhanced sentencing authority under TLOA and VAWA which require publication of the rules and procedures of the court, as well as various other governing documents.[57]

- Objective 3: Revise criminal code to enhance cohesion, incorporate traditions and customs, and begin looking at compliance under TLOA and VAWA.

Perhaps the most impactful step a tribe can take is updating and revising the Tribal Code. Stakeholders and past assessments alike have noted that tribal codes must be updated and unified so that there is a workable base on which the justice system can build upon in its efforts to grow with the increasing needs of the community.

A necessary first step in this process is identifying gaps and inconsistencies in the tribal codes to clarify language and provide consistency in structural references. In addition, updating the codes would provide the opportunity to introduce new offenses that the code does not currently address. It would also present a chance to create a uniform code of ethics to govern the conduct of lawyers, lay advocates, and court personnel. Perhaps most importantly, it provides the tribe with an opportunity to rewrite its laws in a self-determined manner, including the incorporation of traditional teachings and beliefs into the governing structure of the community.

Pursing an updated code would also provide a prime opportunity to develop a code that complies with the requirements for implementation of expanded jurisdiction and

sentencing authority under VAWA and TLOA. There are a number of capacity issues, however, that may arise due to the stringent requirements of both statutes. These include the adoption of speedy trial standards, the adoption of particular evidentiary rules to provide for the right of defendants to confront witnesses, and other revisions. It has been estimated that a revision to get a tribe’s justice system to the point where it would meet the statutes’ requirements for increased sentencing powers could cost up to $500,000.[58] While some tribes may have sufficient resources to do this on their own, other tribes will need substantial assistance to get their court systems to the point where they can exercise the jurisdiction under these statutes. Because this would be such a large undertaking, it would be prudent to seek outside assistance with extensive code development that could implicate VAWA and TLOA sentencing authority.[59]

- Objective 4: Development and Training of Law Enforcement Resources

Developing effective court systems that are able to successfully punish offenders within the increased sentencing authority does little for alleviating social problems if there are inadequate law enforcement resources to bring offenders into the criminal justice system. Law enforcement in Indian Country generally faces six “issue areas” which can affect the success of law enforcement. These six areas are jurisdictional issues, resources for agencies, training and education, coordination and cooperation, response to victims, and prevention and reduction strategies.[60]

Today, criminal jurisdiction in Indian Country is shared between tribal, state, and federal agencies. The sharing of jurisdiction, with no sovereign having full jurisdiction, means that, for each crime, there must be an individualized determination of which agency has the legal authority to investigate the crime. Determining the agency with proper jurisdiction depends on a number of discrete facts about the crime, including the identities of the offender and victim, the type of crime, the legal status of the land where the crime took place, and whether there are any applicable federal laws or agreements that have been entered into by the law enforcement agencies or governments. These complexities have caused well-documented challenges for law enforcement agencies throughout Indian country, with many of these fact intensive inquiries being difficult if not impossible to determine at the time of law enforcement’s first response.[61]

To the extent possible, tribes should strive to develop working relationships with surrounding law enforcement agencies, such as County Sherriff’s Offices. Many tribal law enforcement agencies have entered into cooperative agreements with law enforcement from surrounding jurisdictions. These agreements can be entered into in a number of different ways and include a variety of different subjects, including duties and obligations, jurisdiction, identification of geographic areas, incarceration and prosecution, exchange of information and communication, personnel and equipment, indemnification, liability, dispute resolution, sovereign immunity, binding/non-binding, severability, and termination.[62]

One of the main barriers to this type of agreement is cultural difference and the history of mistrust between the state and tribal agencies and citizens. A general lack of cultural awareness and historical understanding of many tribal members’ inherited distrust of government can lead to misunderstandings and law enforcement tactics which may disrupt community law enforcement relations and further damage agencies’ ability to address and respond to crime in the community.[63] Another concern among law enforcement agencies is training parity between tribal officers and state officers. As will be discussed below, tribal law enforcement agencies often suffer from lack of resources, including training resources. The discrepancy in training between tribal and state law enforcement can be a critical factor that inhibits tribal officers from acting outside of Indian Country under state law. Generally a tribal officer will need to be certified at the state level in order to operate in a law enforcement capacity outside of the reservation. In order to obtain the necessary certifications, tribal officers may be required to receive training at specifically authorized training facilities. This may be difficult due to financial constraints, geographic limitations, or personal characteristics of the trainee.[64]

Despite these challenges, cross-jurisdictional agreements can provide a solution to the problems caused by the complex web of criminal jurisdiction on tribal lands. While local sheriff’s departments are certainly the starting point for tribes that wish to pursue this path, tribes should also advocate for state-wide solutions that set up a framework for these agreements to be applied across the state and across local law enforcement agencies.

Another major challenge for tribal law enforcement agencies is the lack of necessary resources to effectively prevent and respond to crimes committed on the reservation. According to a Department of Justice study in 2002, approximately 1,894 law enforcement officers were working on tribal land, a far cry from the 6,200 officers, estimated by the BIA, needed to provide basic law enforcement services and response on reservations.[65] Additionally, commentators have pointed out that tribal law enforcement agencies have between 55 and 75 percent of the resources and funding available to non-Indian communities.[66] This discrepancy in overall funding is even more stark considering that violent and serious crime in Indian Country occurs at a rate of two times the national average.[67]

This general lack of resources is compounded by interrelated factors that make it difficult for tribal governments to recruit and retain qualified officers, including low pay, high attrition, remoteness of Indian communities, and the dangerous nature of tribal policing.[68] It is common for tribal officers, once they receive training and gain experience, to transfer to police departments in surrounding agencies where the pay and working conditions are better. This results in a turnover rate of approximately 50 percent every two years, costing tribal governments millions of dollars to recruit and train replacements and leading to dangerous gaps in coverage.[69] Another challenge for tribal law enforcement agencies is the vast land mass that is usually covered by a severely limited number of officers. In terms of the land area patrolled, many tribal law enforcement agencies may more closely resemble county or regional police departments, with some tribal departments having to cover over 20,000 square miles of territory.[70] This large geographic area combined with limited officers and vehicle support often results in inadequate coverage and response time to crimes.

To combat these issues, tribes should develop strategic plans to effectively utilize the existing resources to provide support to criminal justice in Indian Country. They should develop comprehensive data collection systems to provide needed statistics for grant and other sources of funding. Tribal governments should also make concerted efforts to centralize and increase the access to technical assistance and grant funding. In addition, tribes should focus on continued lobbying at the federal level to pressure the government to increase funding it provides to tribal justice systems and law enforcement. This can include the sustained funding of programs, but should also include more funding directly to tribal governments in fulfillment of the government-to-government relationship between the sovereigns.

Corporate Engagement

Goal 5: Engage with corporations to create awareness around the intersection of trafficking and the extractive industries, and advocate for inclusion of corporate social responsibility initiatives inclusive of Native rights.

While the causes of trafficking have roots in many factors, the influx of workers during extractive energy development can fuel the rise of human trafficking in a particular location, as occurred in the Bakken. This relatively short-term rise in workers has detrimental impacts on the long-term social and cultural well-being of affected Native communities. All companies are subject to regulations that monitor the environmental impacts of development on the lands and territories surrounding their worksites, but only a few have broadened their perspective to include a meaningful analysis of the social and cultural impacts of development on Native communities.[71]

Corporate engagement is an effective strategy to create meaningful dialogue and make corporations fully aware of the range of development impacts their work may have, especially with respect to the unique set of considerations due to the complexity of federal Indian law and the historical, social, and cultural aspects of Native communities.[72] Ultimately, the goal of engagement is for corporations to take responsibility for the impacts of development through concrete actions.[73] And while companies cannot be held directly responsible for the illegal actions of their employees who commit crimes on their own time, there are several steps that companies can take to ensure the safety and uphold the integrity of the entire community.[74]

For example, in 2016 the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe deployed a corporate engagement strategy with companies and banks funding the Dakota Access pipeline. The strategy quickly gained traction with socially responsible investors and operated parallel to the legal case brought in the federal courts. After a period of research and due diligence regarding the relevant companies, the Tribe, with assistance from First Peoples Worldwide and other allied industry groups, pivoted to engage with the banks that were the major funders of the pipeline. Many banks were put on notice by protests and coordinated letter campaigns of their complicity in funding the project that was executed without the free, prior, and informed consent of the affected indigenous peoples. Ultimately, the largest bank in Norway, DNB, withdrew their $3 million investment from DAPL in direct response to lobbying efforts of the Norwegian Sámi Association, a group of indigenous advocates working toward divestment of banks from DAPL.[75] This brief look at a well-researched and executed strategy demonstrates the efficacy of corporate engagement at influencing the actions of companies and banks to consider and account for the impacts of their investments on the Native communities where they work.

The objectives below lay out the steps necessary for a tribe to deploy a corporate engagement strategy with companies acting on and near their lands.

- Objective 1: Educate relevant tribal stakeholders regarding corporate engagement strategies, shareholder advocacy and corporate social responsibility initiatives.

A first step is to educate tribal stakeholders about the goals and strategies of corporate engagement. Stakeholders may include members of the tribe’s Business Council, the TERO office, in-house counsel, and the tribe’s energy administration departments. Because corporate engagement entails a number of strategies, from setting high-level meetings with corporations to enlisting shareholders of companies to move for change, it is important to understand the purpose and goals of deploying these tactics.[76]

Trainings in corporate engagement specific to indigenous peoples’ advocacy have already been developed by First Peoples Worldwide. The Shareholder Advocacy Leadership Trainings (SALT) are comprehensive trainings designed to build tribal capacity to connect with shareholders and create financial pressure to respect indigenous peoples’ rights.[77] In short, the SALT trainings outline the processes of corporate engagement, provide examples of successful shareholder letter campaigns, and discuss the strategies associated with different tactics from engagement to divestment. Since First Peoples Worldwide is an indigenous-lead NGO with many years of experience advocating for Native rights through corporate engagement, the SALT trainings are maximally aligned with tribal goals and are based on practical experience with these strategies.

- Objective 2: Create a corporate engagement strategy to reach companies in the Bakken and connect with shareholders.

Developing meaningful relationships with oil and gas companies in the region is the first step to effective engagement. Tribes need to research the corporations known to be operating in the area, and then to find those companies that already have human rights policies or, more specifically, policies regarding engagement with indigenous peoples. Identification of corporations in the area can be difficult as many corporations subcontract with multiple operators or use subsidiary corporations during the extractive process.

Next, tribes need to identify those companies that might be willing to be leaders in recognizing the need for social and cultural impact policies in addition to existing environmental policies.[78] Identifying a few companies who are willing to serve as leaders on this issue may provide necessary buy-in for companies to take on this difficult and complex issue. Larger companies like ConocoPhillips and Hess may provide a good starting point. ConocoPhillips, for example, has a human rights policy that explicitly states their commitment to engagement with indigenous peoples consistent with principles in the International Labour Organization Convention 169 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[79]

Corporate engagement strategies require a long-term investment of time and energy to be maximally effective and press corporations to follow, or to develop, and implement principles consistent with accountability to the Native communities where they work. For that reason, tribes contemplating this strategy should appoint at least one person as the coordinator for corporate engagement within the tribal government.

- Objective 3: Advance the principles of corporate accountability within tribal mechanisms

Tribes have authority to exercise regulatory authority over oil and gas companies operating on their reservations, per the civil and regulatory authority in the landmark case Montana v. United States.[80] The relationships created between the corporations and tribes through tribal energy offices or a Tribal Employment Rights Office (TERO) are exactly the type of consensual relationships required by Montana to hold non-Indian entities accountable for their actions on reservations.[81]

Thus, one recommendation is to make adherence to provisions that bolster anti-trafficking measures part of the permitting criteria for outside entities seeking permission ,either through the tribal permitting agency or the TERO office, to operate on tribal land.[82] If companies or their workers were later found to be participating in, or allowing, sex trafficking or drug trafficking, those companies would be subject to penalties through tribal regulatory authority.[83] At a minimum, these newly created provisions recognize the intersection of the extractive industries and human trafficking and create an active dialogue between the tribe and outside entities to ensure the safety of all those living and working on the reservation.

Another way to take a strong stand again human trafficking is to encourage casinos and hotels located on reservations to adopt anti-trafficking policies. In recent years, the hotel and trucking industries have taken notice of the ways that perpetrators have used their services to exploit victims. Several large hotel chains, such as Hilton Worldwide, have adopted policies affirmatively decrying trafficking and instituting training and reporting requirements for employees.[84] Nationally recognized organizations such as the Polaris Project and Code.org have models for writing and implementing this type of policy.[85] By adopting this kind of policy, tailored to Indian country, hotels and casinos operated on Indian lands have an opportunity to be leaders in combatting human trafficking and in ending exploitation of Native women and children in their communities.

The increased presence of extractive industries in and around tribal reservations coincides with a significant increase in criminality, specifically contributing to increased drug use and violent crime that has the potential to affect nearly every tribal member and institution. As a result, tribal infrastructure is almost immediately overwhelmed, and most tribes do not receive an influx of additional resources to address these burgeoning issues. One institution that particularly strains under this situation is the tribal justice system. The caseload of tribal courts can multiply by a factor of ten, while law enforcement resources are faced with an increasing number of criminals and types of crime. Despite these challenging circumstances, tribal justice systems have proven to be resilient, resourceful, and responsive to the needs of their tribal members.