By Tom Watts

Today, the Senate rejected a constitutional amendment that would have reversed many of the Supreme Court’s campaign finance decisions, most notably Citizens United. Combine this with the defeat of the lone Republican candidate for Senate who supported campaign finance reform and was backed by the Mayday SuperPAC, and the past couple days have not been good for campaign finance reform. This should come as no surprise: as I have recently argued, campaign finance reform is a dead end. There are plenty of other good areas of election law to examine, but this one is going nowhere fast.

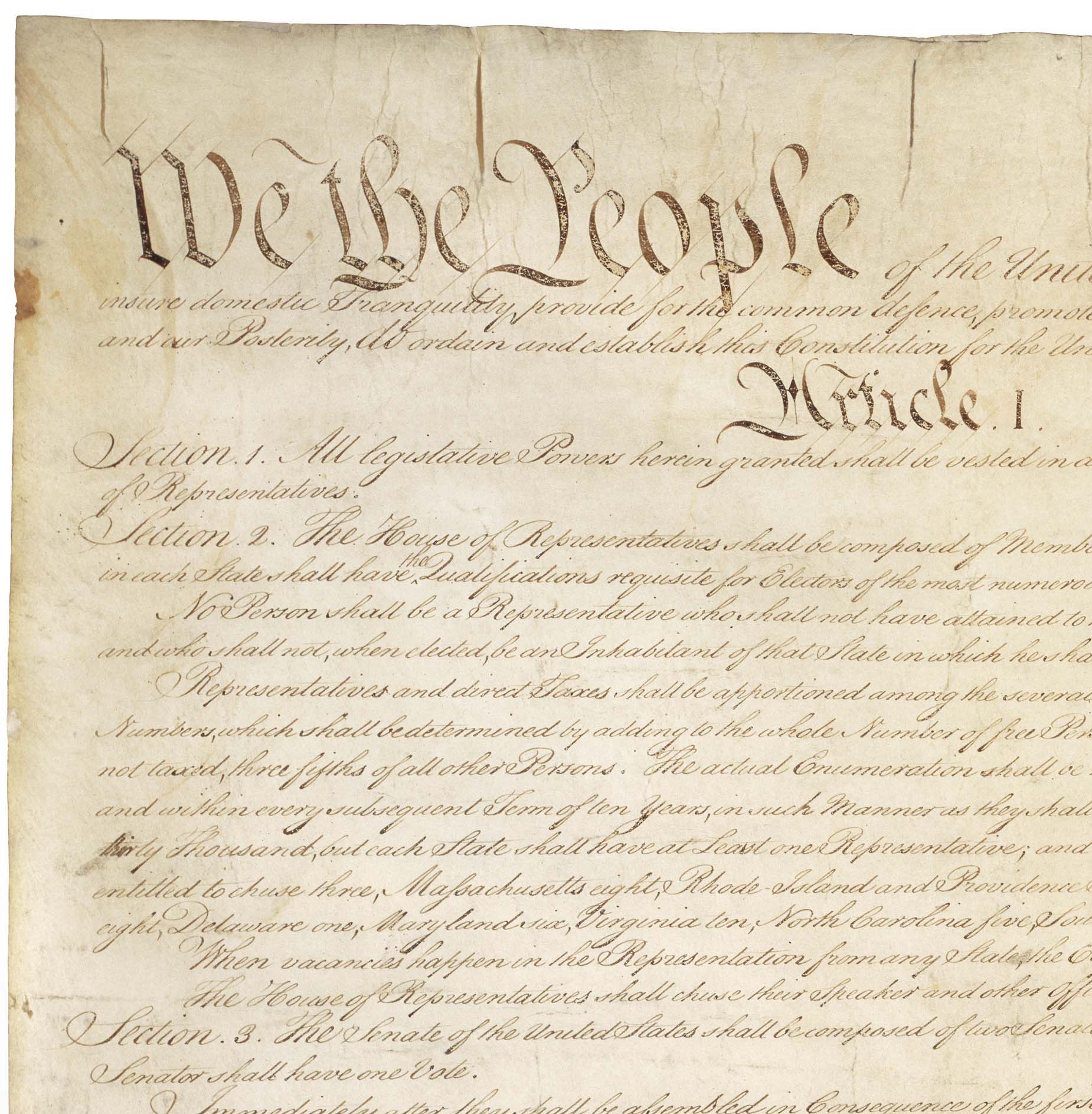

Senate Joint Resolution 19, the failed constitutional amendment, reads as follows:

Section 1. To advance democratic self-government and political equality, and to protect the integrity of government and the electoral process, Congress and the States may regulate and set reasonable limits on the raising and spending of money by candidates and others to influence elections.

Section 2. Congress and the States shall have power to implement and enforce this article by appropriate legislation, and may distinguish between natural persons and corporations or other artificial entities created by law, including by prohibiting such entities from spending money to influence elections.

Section 3. Nothing in this article shall be construed to grant Congress or the States the power to abridge the freedom of the press.

This would reverse not only recent Supreme Court decision that struck down campaign finance laws, such as Citizens United and McCutcheon, but also the part of 1976’s Buckley v. Valeo that struck down the expenditure limits in FECA. Congress could limit as it sees fit.

In my Student Note (linked above), I argued that the constitutional problems with enacting campaign finance statutes are insurmountable given the current Supreme Court, but the failure of SJR 19 illustrates a point to which I gave short shrift: the political problems with enacting a campaign finance constitutional amendment. First, and most crucially, the issue divides along party lines: every Republican voted against SJR 19, while every Democrat voted for it. Even John McCain, coauthor of McCain-Feingold, did not defect. For as long as this pattern persists, unless Democrats gain 67 seats in the Senate, no constitutional amendment will succeed in the Senate. The last time either party held that many seats in the Senate was a half-century ago, and Democrats are unlikely to regain that many Senate seats soon. The House is even worse.

The second problem is that there are some legitimate concerns about such a constitutional amendment. True, many of the arguments against SJR 19 were spurious. Congress has never amended the Bill of Rights before, but doesn’t that just mean that it’s time for an update? How relevant is the Third Amendment to today’s world?

More importantly, however, there are some difficult issues to be weighed with regard to campaign finance and the polarized, partisan news. Section 3 of SJR 19 says that the amendment has no impact on freedom of the press, but where do we draw the line between putting out news and putting out political advertisements? The people who want to reverse a line of Supreme Court decisions presumably do not trust the Supreme Court to draw that particular line, but that’s what SJR 19 would require.

Let’s redirect the energy around campaign finance. Instead of letting conservatives defend the First Amendment, progressives should put conservatives in the uncomfortable position of defending gerrymandering, or arguing against more efficient administration of elections, or in some other indefensible position. Election law is important, and we can win — but not on campaign finance. The past couple days were proof of that.