The Question is Not Whether Humans Make Decisional Errors, But How to Compensate for Them

The Question is Not Whether Humans Make Decisional Errors, But How to Compensate for Them

By Donald R. Philbin, Jr.

ESPN recently dubbed baseball umpire Tim McClelland’s missed calls in Game 4 of the American League playoffs as “the worst umpiring performance at an Angels games since Leslie Nielsen in ‘The Naked Gun.’”1 While his mistakes were not outcome determinative, they rekindled calls for the use of instant replay.

Those of us who have spent time with disputants were not surprised. As New York Yankee Derek Jeter put it: “Umpires are human. They make mistakes sometimes.”2 We routinely anticipate errors and design systemic checks to identify and address them. Appellate courts and appellate arbitration panels, like instant replay, owe their existence to the need for second (or third) looks.

In fact, the ultimate second-looker famously analogized the roll of judges to umpires in his confirmation hearings. Chief Justice John G. Roberts of the United States Supreme Court said, “Judges are like umpires . . . Umpires don’t make the rules; they apply them.”3

In a takeoff from Malcolm Gladwell’s best-selling book Blink, Professor Chris Guthrie drilled into judicial error rates in Blinking on the Bench: How Judges Decide Cases, 93 Cornell L. Rev. 1 (2007). There, law professors asked a large group of trial judges to respond to a three question survey at a judicial conference. Each question has an intuitive, snap answer (a “blink”) and another analytical answer that might be the result of a reasoned opinion. Perhaps unfairly, the questions were not application of law to fact questions that judges might face at work, but analytical quizzes reminiscent of the SAT:

1. A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? 5 (not 10) cents

2. If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets? 5 (not 100) minutes

3. In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half the lake? 47 (not 24) days

The authors reported a 1.23 mean, but parties unable to settle out of court may be more interested in the fact that 31% of the responding judges did not get any of the questions right. There may be inherent problems with this and any survey. The judges may not have put much effort into the break-time quiz at their information packed conference and the questions do not approximate what they are asked to do on the bench. But that is little consolation to those on the “wrong end” of a judgment they forced by not making their own deal in mediation.

Another major study concluded that even parties advised by experienced litigators are not above error.4 Comparing actual trial results with rejected pre-trial settlement offers in more than 4,500 cases and 9,000 settlement decisions made during a 44-year period, the study found that 61% of plaintiffs and 21% – 24% of defendants obtained an award at trial that was the same or worse than the result that could have been achieved by accepting their opponent’s pre-trial settlement proposal. Yet while plaintiffs tend to make more errors in their estimates more frequently, defendants do so with greater severity. When a plaintiff misses the mark, she is only off by an average $43,100. The defendant misses less frequently, but the verdict is 26 times the last offer when he does: $1,140,000.

Psychologists have long taught us that people with exactly the same information reach different conclusions. Buyers rarely want to pay as much as sellers demand, whether negotiating the sale of a house, car, or lawsuit. It’s largely a matter of assigned position. But the magnitude of the decisional error is telling. Subjects asked to price a generic coffee cup for sale assigned it a value of $7.12. Buyers initially offered $2.88 for the same cup – 2.5 times less.4

These studies confirm and quantify what we know intuitively: people (including umpires, judges, litigants, and others) make mistakes and when litigants are wrong, sometimes they are very wrong. The barrier preventing resolution may not be that litigants can’t see the same solution; it may be that they cannot see the same problem.

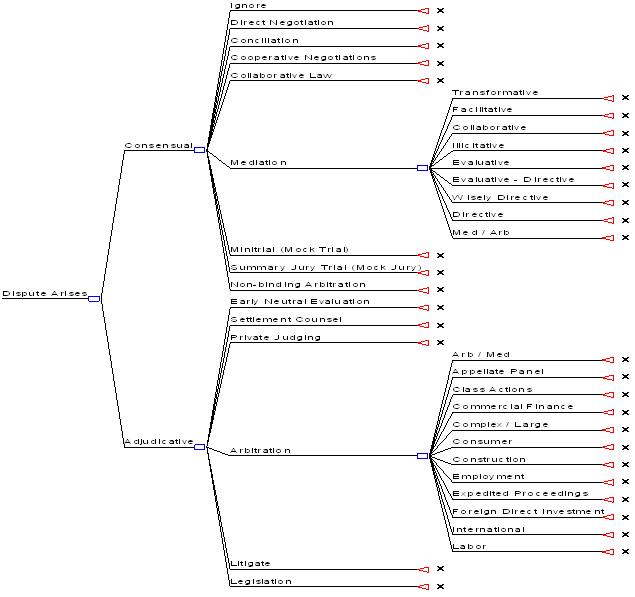

Mediation is a commonly used to debias positional assumptions that lead to impasse. The reality is that we reactively devalue everything our enemy says, even if it would be helpful to us – “that can’t be good for us, or they would not have offered it.” In fact, a Cold War experiment quantified the magnitude of this reactive devaluation bias. Soviet leader Gorbachev made a proposal to reduce nuclear warheads by one-half, followed by further reductions over time. Researchers attributed the proposal to President Reagan, a group of unknown strategists, and to Gorbachev himself. The surprise was not that the group reacted differently to the same proposal depending on its source, but the wide range of difference. When attributed to the U.S. President, 90% reacted favorably. That dropped marginally when attributed to the third-party (80%), but in half (44%) when attributed to the Soviet leader.5

So the surprise is not that an umpire missed a call, it’s how to deal with it systemically. Like litigants, baseball stakeholders have options, and a quick appellate ruling from the pressbox may be the most expedient here since the full record is easily available.

Donald R. Philbin, Jr. is an attorney-mediator, negotiation consultant, arbitrator, and Adjunct Professor at Pepperdine University School of Law — Straus Institute for Dispute Resolution. For more info, see http://www.adrtoolbox.com/.

1 Caple, Jim, Umpire errors a real embarrassment, ESPN.com, Oct. 20, 2009, available at http://sports.espn.go.com/mlb/playoffs/2009/columns/story?columnist=caple_jim&id=4581598

2 Id.

3 Bruce Weber, The Deciders: Umpires v. Judges, N.Y. Times, July 11, 2009, at WK1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/12/weekinreview/12weber.html?_r=1.

4 Randall L. Kiser, et. al, Let’s Not Make A Deal: An Empirical Study Of Decision-Making In Unsuccessful Settlement Negotiations, 5 J. Empirical Legal Studies 551-91 (Sept. 2008), available at http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/121400491/HTMLSTART.

5 Donald R. Philbin, Jr., The One Minute Manager Prepares for Mediation: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Negotiation Preparation, 13 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 249 (2008), available at http://adrtoolbox.com/docs/HNLR_Philbin.pdf

Originally published to HNLR Online on Nov. 1, 2009.