Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Laura Villarraga Albino*

The Artist’s Resale Right (ARR), also known as droit de suite, is an intellectual property right recognized for authors of visual artworks or, after their death, the persons or institutions authorized by national legislation to obtain a monetary interest in any sale of their work in the secondary market. The right, enshrined in Article 14ter of the Berne Convention, mandates specific national legislation to regulate the amount and procedures for collection and is subject to the principle of reciprocity.

Despite volatile art market conditions, a recent report by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC) indicates that worldwide ARR income grew by 4.9% in 2023, representing nearly one-quarter of visual arts collections. In Europe, France, Italy, and Germany saw increases in ARR income of 4.2%, 8.5%, and 25.9%, respectively, while the UK remained the largest collector, amassing EUR 16 million in 2023. Additionally, in the Asia-Pacific region, New Zealand, Australia, and South Korea have expanded their legislation, emphasizing the importance of ARR for the livelihoods and legacies of visual artists.

However, in Latin America, the adoption and enforcement of ARR remain inconsistent. Despite the art market’s substantial growth, reaching a historic high of USD 4.2 billion in 2022—a significant 30% increase from 2021—ARR implementation in the region lags behind its global counterparts.

By considering the growth and visibility of the region’s art market, this article provides a comprehensive overview of ARR in Latin America, discusses two main challenges in its regulation, and outlines some recommendations for its implementation. It is likely that Latin American countries will initiate discussions to align national legislation with international standards for visual artists, ensuring that artists are fairly compensated in the secondary market.

I. The Latin American Art Market

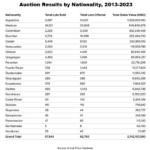

The art market in Latin America has demonstrated significant visibility and growth. Between 2020 and 2023, sales of works by Latin American artists increased by more than 50% compared to pre-pandemic years, exceeding USD 250 million. Specifically, in 2024, sales achieved remarkable milestones, totaling over USD 112 million. In addition, auction data from Artnet, spanning 2013 to 2023, reveals that artists from the region amassed over USD 2.74 billion in total sales from more than 57,000 lots.

This trend includes record-breaking sales, such as Frida Kahlo’s portrait Diego y yo, which sold for USD 34.9 million at Sotheby’s New York in 2021. Additionally, international recognition has increased, with significant representation at major art fairs and exhibitions. For instance, at ARCO Madrid approximately 30% of the participating galleries were from the region, while at the 2024 Venice Biennale one-third of the artists were from Latin America. This reflects the growing presence of Latin American art on the global stage.

Despite this growth, the absence of effective ARR legislation leaves artists at a disadvantage compared to their peers in other regions, thereby eliminating potential benefits from secondary sales and limiting the expansion of their rights.

II. The Resale Right in Latin America

Although Latin American countries have ratified the Berne Convention, the actual implementation of ARR remains largely insufficient. Current legislation across the region shows that two jurisdictions—Argentina (Law 11,723 of 1933) and Cuba (Law 154 of 2022)—do not recognize the right at all. Furthermore, sixteen countries have adopted ARR but have not yet established a functional legal or administrative framework for its collection and enforcement. To date, only Uruguay (Law 9,739 of 1937) effectively collects and distributes ARR royalties.

That leaves 95% of countries with inadequate implementation of the right despite its adoption in national legislation in most cases. The outcome? Under the reciprocity principle, artists cannot benefit from either local or international sales, creating “growing inequalities and imbalances between different regions and income streams [.]”

Considering the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) guidelines, at least two significant challenges arise in configuring the right in Latin America: the rate charged and the administration of ARR—two crucial aspects that the Berne Convention leaves to national regulation.

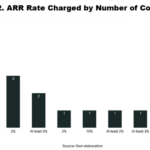

A. The Rate Charged: Fixed, Sliding, or with Minimums and Caps?

In establishing the rate structure, the region presents a diverse landscape of regulatory approaches. Some Latin American countries have established fixed rates from 2% to 10% of the resale price, with Guatemala at the higher end. Other countries stipulate ‘at least’ 2%, 3%, or 5% of the price, suggesting that negotiating a higher percentage is possible. This, in practice, creates uncertainty and administrative complexity and can even be used as an excuse for non-compliance. Only Mexico has introduced a sliding scale, from 1.5% to 4% depending on the resale price.

Yet more problematic is that some Latin American countries—Brazil, Chile, and Ecuador—tie royalties to the increase in the artwork’s value between the first and subsequent sales. This method, however, conflicts with the fundamental idea of ARR. Rather than recognizing resale royalties as other exclusive economic rights granted to authors, this approach awards payment only if the resale generates a profit, treating the artist as a partner in the buyer’s investment.

Furthermore, this practice has hampered enforcement. Regional experiences indicate that this approach is not advisable, as it poses significant enforcement challenges stemming from the need for full disclosure of resale details to accurately determine actual profits. Additionally, it fails to account for factors such as currency fluctuations, inflation, and the inherent difficulty of verifying previous valuations.

As noted by Fabiana Nascimento, Director of Visual Arts at AUTVIS (Associação Brasileira dos Direitos de Autores Visuais), “[t]he Artist’s Resale Right in Brazil was recognized in 1981 […] [but] it has been very difficult to apply […], as it defines the charge through the difference in values (prices) between the sales of the work, which in a country that has had six currency changes in the last 50 years is practically impossible”. Similarly, the Chilean ARR legislation is currently being amended due to its practical inconveniences.

Moreover, when determining the rate, it is also important to consider the establishment of caps or thresholds as a condition to recognize the right, as in the European Union. However, in Latin America, discussions about caps have been limited for two primary reasons. Firstly, many local art markets are still maturing and have yet to see the astronomical sales common in Europe or the United States. Indeed, while one of the most expensive sales in Latin America was Paisaje de calicanto azules (1932) by Olga de Amaral, which sold for USD 225,633.47 in 2021 at BogotaAuctions, Klimt’s Lady with a Fan (1917–18) fetched USD 108.4 million at Sotheby’s London in 2023.

Secondly, laws in Latin American countries, following a continental approach of droit d’auteur, tend to be strongly pro-artist, at least in principle. As a result, establishing a minimum economic threshold for recognizing this right may be perceived as unfair, as it could undermine the acknowledgment of an author’s rights regardless of the associated administrative costs for art market professionals (AMPs). Essentially, the right should be upheld for artists irrespective of the burden on these professionals, ensuring that even modest or minimal royalties are duly paid.

Although caps and thresholds might help protect the market, interviews with European CMOs indicate that the current rate structure, unchanged since 2001, requires revision. For instance, ADAGP (Société des Auteurs dans les Arts Graphiques et Plastiques) notes that the existing cap may not align with today’s record art prices, potentially limiting artists’ earnings from high-value sales. Likewise, DACS (Design and Artists Copyright Society) emphasizes that while the initial minimum threshold might have been justified when the regulation was introduced, administrative costs have since decreased, resulting in the exclusion of many artists and diminishing the overall impact of the right.

B. Administration of ARR: Individual, Collective, or Mandatory?

Similarly to the rate of ARR, Article 14ter provides no specific guidelines on the administration of the right, leaving national legislators a range of options. Thus, administration may be conducted by the author and/or a CMO on either a voluntary or mandatory basis.

Notably, collective management is often regarded as the more efficient mechanism for administering the right, and in countries that successfully implement ARR, CMOs play a pivotal role. However, in Latin America, only 35% of countries have established CMOs, leaving the remaining 65% to individual management—with all the associated difficulties this implies for artists in collecting the royalty.

In countries where CMOs exist, ARR collection can still be challenging due to unregulated rates and unclear collection and distribution processes. For instance, in Brazil (AUTVIS), Chile (CREAIMAGEN) and Argentina (SAVA—Sociedad de Artistas Visuales Argentinos), ARR collection remains largely underdeveloped despite many efforts by these organizations to regulate or amend existing ARR regulations. Regarding other CMOs, there is insufficient information about their functioning and awareness of ARR, such is the case of Ecuador (ARTEGESTIÓN) and Peru (APSAV—Asociación Peruana de Artistas Visuales).

In most cases, collective management is voluntary regardless of the establishment of CMOs, as is the case in Uruguay. In other countries, legislation states that collective management is not compulsory, allowing authors the autonomy to manage their rights directly or through CMOs. Such is the case of Colombia, where the Constitutional Court has expressly ruled out mandatory collective management. Despite this, CMOs remain the only mechanism to grant the collection of ARR in international sales due to sister societies.

Lastly, Venezuela is the sole country with legislation that mandates collective management, yet its CMO, AUTOARTE, has ceased operations. Thus, without an active CMO, such regulation loses any practical application in favor of the artists.

C. A Successful Case: Uruguay and Prospects for Mexico

There is, however, a beacon of hope. Uruguay stands out for its effective enforcement of ARR. Although the country first adopted the right in early 1937, the regulation was amended in 2003 to introduce a 3% fixed rate on resale prices—an approach that has since yielded meaningful results.

Today, Uruguayan artists may collect individually or through AGADU (Asociación General de Autores del Uruguay), which manages ARR on behalf of APEU (Asociación de Pintores y Escultores del Uruguay) members. In addition, AGADU’s efforts have resulted in robust enforcement and public awareness of the right. Furthermore, two court rulings have consistently reinforced the relevance of ARR by reaffirming the auctioneer’s obligation to pay the resale royalties.

To ensure compliance, Uruguayan legislation established a duty for AMPs to notify resales. While AGADU actively requests resale information and even attends auctions to verify sales, compliance among dealers and galleries still largely depends on truthful declarations, making enforcement more challenging compared to auctioneers. Despite these practical challenges, effective regulation is in place, and last year, over EUR 50,000 were collected in ARR royalties, becoming a significant source of income for artists.

Meanwhile, in January 2023, Mexico formally set the tariffs for ARR collection without objections after a public consultation. While it is still too early to assess its impact, Mexico, as one of the major art markets in Latin America, could potentially initiate discussions about balancing administrative costs for AMPs.

III. Looking Ahead

The growth of Latin America’s art market presents a unique opportunity to discuss the implementation—and perhaps even the harmonization—of the resale right. While most countries in the region have adopted the right, effective implementation remains rare.

Countries exploring its regulation, however, can learn from Uruguay’s model. A straightforward regulatory framework with a fixed rate, robust collective management, and institutional support can help provide adequate protection for visual artists. By creating effective mechanisms to collect royalties and report resale information, it is possible to enhance the capacity to monitor transactions and enforce compliance in a market often characterized by informality and secrecy.

In the meantime, supporting the establishment of CMOs in the region, although not mandatory, will be crucial to facilitate the collection in international sales. Additionally, further research into local art markets could provide valuable data for legislators, CMOs, and other stakeholders to refine regulatory measures. Lastly, raising awareness among AMPs about the importance of the resale right for artists will be crucial for fostering compliance and strengthening transparency within the art ecosystem.

It is time for Latin America to address the effective regulation of ARR. By closing these gaps, Latin American countries can ensure visual artists benefit from the enduring success of their works in the international market, promote transparency in art-market practices, and align regional intellectual property rights with global standards.

[hr gap=”1″]

Laura Villarraga Albino is a Lawyer and Art Historian with a Master’s in Intellectual Property Law from the University of the Andes (Colombia) and an LLM in Art, Business, and Law from Queen Mary University of London. She currently provides legal counsel to creators, designers and art market participants. Her research focuses on the Artist’s Resale Right and actively promotes its regulation in Latin America.