Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Chad Patrick Osorio*

I. Introduction

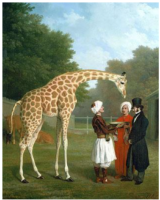

The intersection of art and wildlife conservation raises critical questions about the role of cultural expression in addressing environmental challenges. Art has historically depicted nature and human-wildlife interaction, illustrating the connection between humans and the natural world. It has also, however, inadvertently contributed to the illegal wildlife trade (IWT), particularly when art has increased the social acceptability and desirability of owning and hunting wildlife. Examples include Leonardo da Vinci’s The Lady with an Ermine (c. 1489–1490), Peter Paul Ruben’s The Tiger Hunt (c. 1615–1616), and Jacques-Laurent Agasse’s The Nubian Giraffe (c. 1767–1849). Additionally, wildlife products have been used in the creation of art, including plant and animal dyes for paintings and textiles, as well as wood, bone, and horns for ornamentation, trinkets, and sculptures. Both examples are evident in the artistic traditions of Southeast Asia.

(Images are provided by the author)

Southeast Asian art, both past and present, richly incorporates depictions of and references to wildlife. Examples of this include illustrations from Thai horoscope manuals in the 1800s, an early deity carving from ivory, and an antique Balinese rosewood sculpture of a mythical beast, among many others. These artworks resonate with the region, which is home to some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems and harbors iconic species like tigers, elephants, and hornbills. These species are not only ecologically significant but also hold deep cultural value. However, this rich biodiversity is under severe threat from the illegal wildlife trade. Despite stringent international conventions such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), IWT remains a multi-billion-dollar industry and one of the most lucrative illegal activities in the world. IWT presents numerous challenges, with wide-ranging impacts that affect both the natural environment and human society. Its consequences are significant and multifaceted, spanning environmental, economic, political, and social dimensions.

Southeast Asian countries serve as crucial source, transit, and destination points for wildlife trafficking. Due to their highly porous borders, rapidly growing middle class, and deeply entrenched cultural practices, these countries face unique challenges in addressing this issue. One contributing factor to the underground wildlife market is that derivative products of flora and fauna are trafficked for use in traditional and contemporary works of art. In this article, we seek to shift this perspective and instead explore how international legal frameworks protecting art can be leveraged to protect wildlife within the regional jurisdiction of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The article is organized as follows: in Part II, we discuss specific cases of some of the most trafficked wildlife in relation to art, including elephant ivory, hornbill casques, hawksbill tortoiseshells, and rosewood and agarwood timber. We outline the current legal conservation framework in the region, giving examples under both treaty and domestic law in Part III. In Part IV, we propose how existing legal protection for art and heritage within the ASEAN can contribute to wildlife protection, capitalizing on market regulation for sustainability. We conclude, in Part V, with an ASEAN-led sustainable art certification program seeking to increase the joint value of nature in ASEAN art.

II. Art and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

The art market—both legal and illicit—has a long history of using wildlife products. Items such as ivory sculptures, mother-of-pearl inlays, and exotic leather crafts are prized for their aesthetic and cultural value. In Southeast Asia, traditional and religious art often incorporates these materials, creating tension between cultural preservation and wildlife conservation.

One of the most glaring examples of art driving wildlife exploitation is the ivory trade. Ivory, derived from the tusks of elephants, has been used for centuries in carving intricate sculptures, religious artifacts, and decorative items. Ivory carvings are highly sought after for their cultural and aesthetic value, particularly in the historical production of religious figurines. Despite the ban on the international trade of ivory, demand persists, exhibited by high ivory prices in Asia. Poachers and traffickers exploit legal loopholes, smuggling ivory to and from Southeast Asia, where artisans transform them into works of art. This demand contributes significantly to the decline of elephant populations, particularly the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus spp.), which is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Another example is the use of helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) casques in jewelry and ornamental art. Known as “red ivory,” the solid keratin casques are carved into intricate designs that are highly valued in East and Southeast Asia. The helmeted hornbill, native to Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand, faces critical endangerment due to poaching driven by demand for its casques. The species plays a vital ecological role as a seed disperser, and its loss has cascading effects on forest ecosystems. Despite international protections, the helmeted hornbill continues to be targeted, with traffickers smuggling casques through clandestine networks.

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), classified as critically endangered, is another species victimized by the art market. Its tortoiseshell is used to craft jewelry, combs, and decorative items. In the Philippines, tortoiseshell crafts have a long tradition, particularly in coastal communities. The exploitation of hawksbill turtles for art not only threatens their survival but also disrupts marine ecosystems, where they play a role in maintaining coral reef health. The continued demand for tortoiseshells highlights the need for stronger enforcement.

Plants also play a significant role in the illegal trade linked to art. Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.), prized for its deep red hue and durability, is commonly used in furniture and carvings. Rosewood smuggling is a pervasive issue in countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, where forests are stripped of this valuable resource to meet international demand. The exploitation of rosewood for luxury goods has led to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and illegal logging operations that endanger local communities. Similarly, agarwood (Aquilaria spp.), used in perfumes, incense, and intricate carvings, is overharvested due to its high market value. Native to several ASEAN countries, agarwood trees are now critically endangered in many areas, further threatening forest ecosystems.

These are just some examples of wild flora and fauna, from land, sea, and air, trafficked within Southeast Asia to serve the global demand for art.

III. Legal Frameworks Protecting Wildlife in ASEAN

There are existing legal protections for wildlife in Southeast Asia, led foremost by ASEAN—a regional intergovernmental organization that promotes political and economic cooperation among ten Southeast Asian countries. Founded on August 8, 1967, through the signing of the ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, ASEAN has since grown to include Brunei Darussalam (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos (1997), Myanmar (1997), and Cambodia (1999). ASEAN’s core objectives are to foster regional peace and stability, stimulate economic growth and prosperity, and enhance cooperation among its Member States.

ASEAN places much emphasis on principles such as mutual respect, non-interference, consensus-building, and collaboration. The regional body seeks to ensure that Member States acknowledge each other’s sovereignty and refrain from actions that could undermine national interests or be perceived as external intervention in domestic affairs. Consensus-building is equally central to ASEAN’s decision-making process, requiring unanimous agreement among its members, which ASEAN implements through regular meetings and consultations. Through this cooperative political-legal framework, the regional organization has developed various policies and programs to promote interstate cooperation in trade and investment, regional security, social and cultural matters, and sustainable development. Among its notable accomplishments is the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which seeks to create a unified market and production base, enabling the free movement of goods, services, investments, and skilled labor within the region. As a result of these efforts, as of 2022, ASEAN has emerged as the fifth-largest economy globally.

ASEAN countries are signatories to various international conventions aimed at curbing illegal wildlife trade. The most significant is CITES, which regulates the international trade of endangered species. This is supported by regional initiatives like the ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN), which facilitates cooperation among Member States to combat wildlife trafficking, providing a platform for sharing intelligence and best practices among enforcement agencies. Similarly, the ASEAN Working Group on CITES and Wildlife Enforcement aligns Member States with CITES requirements and enhances enforcement capabilities.

Each ASEAN country has its own set of laws addressing wildlife conservation and illegal trade. For instance, Thailand’s Wildlife Conservation and Protection Act (2019) criminalizes the possession and trade of protected species and their derivatives. Indonesia’s Law on Conservation of Biological Natural Resources and their Ecosystems (1990), recently updated, includes provisions for wildlife trafficking, imposing penalties for trading endangered species. In the Philippines, the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act (2001) prohibits the exploitation of endangered species for commercial purposes. Despite these frameworks, enforcement challenges persist, including corruption, lack of resources, and inadequate cross-border collaboration. Below is the table of domestic legislation in support of wildlife protection in the ASEAN region.

Table 1. CITES-related Laws in ASEAN Countries

IV. Exploring Legal Synergy between Art and Conservation Law

The question remains: how can art law support these wildlife conservation initiatives? After all, art law is a specialized legal field addressing the creation, ownership, sale, and protection of art, encompassing intellectual property rights, cultural heritage preservation, provenance verification, and market regulation. Nature conservation law, on the other hand, focuses on safeguarding natural resources, biodiversity, and ecosystems, regulating activities like hunting, fishing, logging, and trade to prevent environmental degradation. In this section, we explore how integrating these two domains can offer a promising tool to address the use of wildlife products in art, particularly in the ASEAN region.

One potential initiative involves merging intellectual property protection with eco-labeling certifications. Geographical indications (GIs), which identify products with qualities tied to their origin, could be expanded to certify products as sustainably sourced and wildlife-friendly. This approach, in line with the One Village, One Product campaign led by ASEAN, could protect sustainable wildlife use while fostering community-based practices. This strategy unites conservation, intellectual property, and cultural heritage for a common cause.

As envisioned, the enhanced GI certification would include sustainability and wildlife-friendly practices as core criteria. Commercially available art and heritage products such as textiles, wood carvings, and agricultural goods would need to meet these standards to earn the ASEAN-approved label. This certification scheme would offer significant benefits for wildlife protection. Encouraging alternative sustainable materials and ethical production practices decreases reliance on resources derived from endangered species. The overexploitation of high-value wood carvings could be curtailed through the certification of sustainably sourced wood. Additionally, discouraging the use of endangered wildlife derivatives such as ivory or hornbill casques at the grassroots level supports supply-induced demand reduction of these illegal products.

Moreover, the scheme uplifts community-based approaches by linking sustainability to products deeply rooted in local traditions and indigenous knowledge. Many GI art products reflect cultural identity and heritage. By adopting eco-focused practices and providing government support for alternative wildlife-friendly materials, artisans can act as stewards of both cultural and natural resources, preserving their traditions while supporting conservation. Artisans and woodworkers across the region can integrate sustainable sourcing without compromising their craft’s authenticity. Capacity-building initiatives, such as training artisans on sustainable methods, would strengthen community resilience, protect socio-economic rights, and ensure long-term benefits.

Economic incentives further bolster this approach. Certified products command higher market value, attracting ethical consumers who prioritize sustainability and conservation (a global market enjoying steady market growth). This can create a cycle where increased demand for certified products motivates communities to adopt wildlife-friendly practices, amplifying conservation impacts. At the same time, campaigns can be launched to attach stigmas to art products that are not sustainably sourced. By associating non-sustainably sourced wildlife products with negative social and ethical connotations, campaigns can discourage consumer demand and shift market preferences toward certified alternatives. Public awareness initiatives, celebrity endorsements, and policy interventions can reinforce these stigmas. This helps make unsustainable products less desirable and even socially unacceptable. Over time, such stigmatization can pressure artisans and commercial art producers to transition toward sustainable sourcing practices to maintain market credibility and consumer trust. These campaigns go hand-in-hand with labeling requirements and trade restrictions and make it easier for consumers to distinguish between ethical and unethical products.

Implementing this scheme in Southeast Asia requires careful planning and collaboration among Member States. ASEAN policymakers must set clear standards and enforcement mechanisms. Partnerships with other international bodies as well as academia can provide funding and technical expertise, while community leaders, Indigenous Peoples, and civil society can work together to adapt traditional practices to meet sustainability criteria without losing cultural authenticity.

V. Conclusion

One of the most significant challenges in the use of wildlife in art is balancing cultural preservation with conservation. Traditional art forms that rely on wildlife products must adapt to modern conservation ethics without losing their cultural significance. In line with ASEAN’s goal of a common regional market, facilitating both supply and demand for wildlife-friendly art can incentivize artisans to adopt sustainable practices and influence social norms for wildlife protection. To spearhead this, an ASEAN-led art certification program can help consumers identify and support ethical and environmentally responsible art.

Based on this premise, art law holds immense potential to support the protection of wildlife in the ASEAN region. However, this potential can only be realized through regional cooperation, an integrated legal framework, and community engagement. By aligning the art world with conservation goals, ASEAN can transform a significant challenge into an opportunity for preserving its rich biodiversity and cultural heritage.

[hr gap=”1″]

*Chad Patrick Osorio is a current PhD Researcher at Wageningen University and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines Los Banos. He thanks Dasha Gretchikine (Wageningen University) for the editorial support and Carl Kristoffer Hugo (University of the Philippines Los Banos) for the research assistance.