Dec 28, 2013 | Op-Ed

Over the past two decades, and in several regions of the world, there has been an expansion of judicial power. In this same time period, there has also been a growing interest in, and rather heated debate concerning, the relationship between democracy and nationalism. Scholars in all regions of the world, not least of all Europe, are searching for institutional arrangements that might effectively, and democratically, help polities best accommodate difference.

This article brings together separate bodies of literature on these two global developments: the expansion of judicial power, and the challenges of accommodating difference in democracies. The article proceeds in four steps. The first section presents claims from an important body of literature concerning the U.S. Supreme Court and American democracy and suggests why this literature is useful for understanding current trends in Europe. The second section shifts focus and discusses several “toleration regimes”—or ways of organizing difference—in the world, and their role in diverse societies. The third section then argues that there is a direct relationship between these specific toleration types, and the strength of judicial activism. Drawing these arguments together, the final section concludes that in Europe, for better or for worse, several activist constitutional courts are shaping democracy with adjudication, by moving countries toward specific toleration regimes and away from others.

Read full article (PDF)

Dec 27, 2013 | Op-Ed

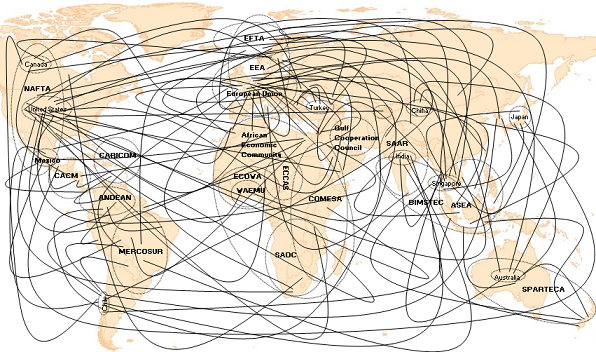

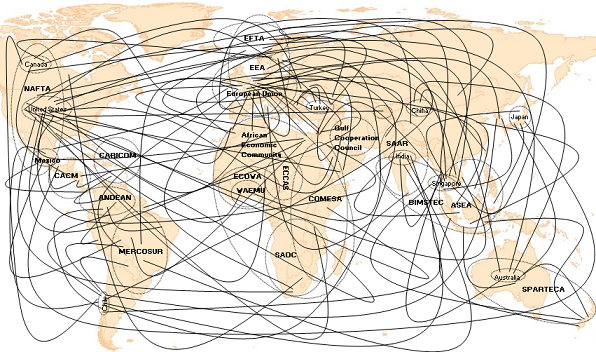

A recent book honoring Detlev Vagts takes stock of established fields of “transnational law,” such as the protection of property and investment. The book also explores new areas of law that are in the process of detaching themselves from the nation-state, such as global administrative law and the regulation of cross-border lawyering, including in the arbitration context. Vagts’ seminal coursebook, “Transnational Legal Problems,” originally co-written with Henry Steiner in the 1960s, seeks to develop a conceptual framework for understanding transnational problems, i.e., those problems that involve more than one legal and political system. By reaching beyond traditional legal boundaries, that book has been instrumental in promoting non-compartmentalized legal thinking, and the same can be said about the transnational-law approach in general.

In his foreword to the Vagts Festschrift, Harold Hongju Koh, a former dean of Yale Law School and a prominent transnationalist, defines what he calls “transnational legal process” as “the theory and practice of how public and private actors interact in a variety of public and private, domestic and international fora to make, interpret, internalize, and enforce rules of transnational law.” According to Koh, transnational legal process:

focuses on the transnational, normative, and constitutive character of global legal process: transnational, in the sense of cutting across historical private-public, domestic-international dichotomies: normative, in the sense of illustrating how legal rules generated by interactions among transnational actors shape and guide future transnational interactions; and constitutive, in the sense of dynamically mutating from public to private, domestic to international and back again in a way that reconstitutes national interests.

A particularly instructive example, or manifestation, of transnational legal process, as defined above, is the application and interpretation of norms of international economic law embedded in investment treaties in the course of resolving disputes between foreign investors and states hosting their investments through the instrument of arbitration as an alternative to litigation.

As such, investment treaty arbitration lies squarely at the interface between national and international developments. The disputing parties and their adjudicators, called “arbitrators,” typically represent different legal and political systems. In investment arbitrations, the private sector, represented by individual or corporate investors, confronts the public sector, represented by host country governments. Moreover, public law, not only public international law but also host country regulations and administrative decision-making by state actors, meets private law, especially in cases involving an alleged breach of contract based on an “umbrella clause” in an investment treaty and in cases governed by public international law as well as host state law. Rather than being governed by one set of laws, investment disputes routinely involve multiple sets of legal norms, i.e., various national laws and bilateral and multilateral treaties, all in the context of fact-intensive cases stemming from complicated long-term relationships between foreign investors and host countries.

A transnational-law based approach analyzes the complexities of investor-state arbitration from the perspective of an interactive process involving the various participants and stakeholders in investment arbitrations, i.e., both state and nonstate formal participants as well as nonstate actors as informal interlocutors. In this context, the following stakeholders or actors who may influence the ultimate outcome of investor-state cases can be identified:

- Individual or corporate investors as claimants

- Sovereign states or state entities as respondents

- Arbitrators as gatekeepers (jurisdiction) and decision-makers

- Party counsel and expert witnesses as decision-shapers

- Arbitral institutions as administrators

- NGOs as public interest representatives or amici curiae

These various stakeholders have not been fully examined in the literature, but their roles and contributions need to be understood to appreciate the regime in which they operate and, especially, the challenges that regime faces. This article will argue that the challenge of recalibrating the investment treaty arbitration system to the satisfaction of the system’s various stakeholders is best met through a transnational-law approach, given the advantages offered by the inherent non-compartmentalized nature of such an approach.

A transnational-law approach to analyzing and understanding contemporary issues of investment treaty arbitration with a view to accomplishing a widely acceptable recalibration of the investment treaty arbitration system best reflects the hybrid, sui generis nature of the developing phenomenon of investor-state arbitration and the fact that “[t]he investment system exists at the intersection of multiple fields.” Investment treaty arbitration, which is the preferred method for resolving today’s investment disputes, is best understood as a process blending the rules and customs or traditions pertaining to arbitration between commercial parties—itself a blending of Common Law and Civil Law concepts and developed domestically before being adapted to international settings—with the rules and customs or traditions of public international law, including institutions such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Clarifying and appreciating this blending of systems—not only the rules but also the customs and traditions associated with each—will guide arbitrators in defining the content of rules of international law they are charged with applying in individual cases, and will help those affected by their decisions in understanding and accepting the process underlying these decisions and the rulings themselves.

Read full article (PDF)

Source: UNCTAD.

Mar 7, 2012 | Op-Ed

The iron rule of the Asad dynasty over Syria’s people is forty-two years old. It began in 1970 when then Defense Minister Hafez al-Asad carried out a bloody coup against his own party colleagues and appointed himself president. Hafez, the family patriarch and dictator for life, killed or jailed companions he perceived as his rivals, supported violent extremism whenever he found it useful, and plundered Syria’s riches while arresting and torturing any dissenter. Over two generations of Asads, a brutal government in Damascus has been the main Mideast ally of an increasingly belligerent Iran. Bashar al-Asad, the son, has acted as the chief facilitator for Sunni extremist killers in Iraq over the past ten years. In Lebanon, Asad’s father and son have wrought havoc since 1975, killing in turn Palestinians, Muslim Lebanese, Christian Lebanese, and whoever dared help the return of stability to a country torn asunder. They assassinated the most prominent Lebanese leaders who stood in their way, including Kamal Jumblat in 1977, Bashir Gemayel in 1982, and in all likelihood Rafik Hariri in 2005. Operatives of self-proclaimed “Loyal to Asad’s Syria” Hizbullah are now under indictment before the Special Tribunal of Lebanon for Hariri’s murder, and scores of journalists and politicians along with hundreds of other innocent people have been assassinated, “disappeared,” or randomly killed.

Most tragically, the Asads never hesitated to commit mass murder against the Syrians. Hama’s historic center was leveled to the ground in 1982, and the relentless siege, bombardment, and mass killing continues to this day a pattern of ruthless governance across the country, with Homs the latest victim.

Both the future of the Middle East and the success of the formidable nonviolent mass movement in Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, and Yemen depend on what happens next in Damascus. If the dictatorship survives, if its main pillars are not brought to justice on the way to a democratic transition, Asad’s continued rule will doom domestic and international peace in the region and beyond. Why? Because the nonviolent movement will find it hard to recover from this blow. Asad’s regime itself will have its own noxious effect on peace. Yet more deeply, more world-historically, it will be harder—much harder—to argue to any brave young man or woman cleaving to nonviolence that this path, although potentially bloody in sacrifice, is the right form of resistance to tyranny.

Our joint reflection seeks to bring recognition to the unparalleled bravery and sustained nonviolent resistance of Syria’s revolution and to provide concrete political means to help end the forty-two year long reign of death and fear. Drawing on the appropriate tools of international law and the strength of Syrian revolution, the ends and the means of the strategy proposed must remain worthy of the sacrifice of Syria’s thousands of nonviolent demonstrators.

Read full article (PDF)