Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Laura Villarraga Albino*

The Artist’s Resale Right (ARR), also known as droit de suite, is an intellectual property right recognized for authors of visual artworks or, after their death, the persons or institutions authorized by national legislation to obtain a monetary interest in any sale of their work in the secondary market. The right, enshrined in Article 14ter of the Berne Convention, mandates specific national legislation to regulate the amount and procedures for collection and is subject to the principle of reciprocity.

Despite volatile art market conditions, a recent report by the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC) indicates that worldwide ARR income grew by 4.9% in 2023, representing nearly one-quarter of visual arts collections. In Europe, France, Italy, and Germany saw increases in ARR income of 4.2%, 8.5%, and 25.9%, respectively, while the UK remained the largest collector, amassing EUR 16 million in 2023. Additionally, in the Asia-Pacific region, New Zealand, Australia, and South Korea have expanded their legislation, emphasizing the importance of ARR for the livelihoods and legacies of visual artists.

However, in Latin America, the adoption and enforcement of ARR remain inconsistent. Despite the art market’s substantial growth, reaching a historic high of USD 4.2 billion in 2022—a significant 30% increase from 2021—ARR implementation in the region lags behind its global counterparts.

By considering the growth and visibility of the region’s art market, this article provides a comprehensive overview of ARR in Latin America, discusses two main challenges in its regulation, and outlines some recommendations for its implementation. It is likely that Latin American countries will initiate discussions to align national legislation with international standards for visual artists, ensuring that artists are fairly compensated in the secondary market.

I. The Latin American Art Market

The art market in Latin America has demonstrated significant visibility and growth. Between 2020 and 2023, sales of works by Latin American artists increased by more than 50% compared to pre-pandemic years, exceeding USD 250 million. Specifically, in 2024, sales achieved remarkable milestones, totaling over USD 112 million. In addition, auction data from Artnet, spanning 2013 to 2023, reveals that artists from the region amassed over USD 2.74 billion in total sales from more than 57,000 lots.

This trend includes record-breaking sales, such as Frida Kahlo’s portrait Diego y yo, which sold for USD 34.9 million at Sotheby’s New York in 2021. Additionally, international recognition has increased, with significant representation at major art fairs and exhibitions. For instance, at ARCO Madrid approximately 30% of the participating galleries were from the region, while at the 2024 Venice Biennale one-third of the artists were from Latin America. This reflects the growing presence of Latin American art on the global stage.

Despite this growth, the absence of effective ARR legislation leaves artists at a disadvantage compared to their peers in other regions, thereby eliminating potential benefits from secondary sales and limiting the expansion of their rights.

II. The Resale Right in Latin America

Although Latin American countries have ratified the Berne Convention, the actual implementation of ARR remains largely insufficient. Current legislation across the region shows that two jurisdictions—Argentina (Law 11,723 of 1933) and Cuba (Law 154 of 2022)—do not recognize the right at all. Furthermore, sixteen countries have adopted ARR but have not yet established a functional legal or administrative framework for its collection and enforcement. To date, only Uruguay (Law 9,739 of 1937) effectively collects and distributes ARR royalties.

That leaves 95% of countries with inadequate implementation of the right despite its adoption in national legislation in most cases. The outcome? Under the reciprocity principle, artists cannot benefit from either local or international sales, creating “growing inequalities and imbalances between different regions and income streams [.]”

Considering the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) guidelines, at least two significant challenges arise in configuring the right in Latin America: the rate charged and the administration of ARR—two crucial aspects that the Berne Convention leaves to national regulation.

A. The Rate Charged: Fixed, Sliding, or with Minimums and Caps?

In establishing the rate structure, the region presents a diverse landscape of regulatory approaches. Some Latin American countries have established fixed rates from 2% to 10% of the resale price, with Guatemala at the higher end. Other countries stipulate ‘at least’ 2%, 3%, or 5% of the price, suggesting that negotiating a higher percentage is possible. This, in practice, creates uncertainty and administrative complexity and can even be used as an excuse for non-compliance. Only Mexico has introduced a sliding scale, from 1.5% to 4% depending on the resale price.

Yet more problematic is that some Latin American countries—Brazil, Chile, and Ecuador—tie royalties to the increase in the artwork’s value between the first and subsequent sales. This method, however, conflicts with the fundamental idea of ARR. Rather than recognizing resale royalties as other exclusive economic rights granted to authors, this approach awards payment only if the resale generates a profit, treating the artist as a partner in the buyer’s investment.

Furthermore, this practice has hampered enforcement. Regional experiences indicate that this approach is not advisable, as it poses significant enforcement challenges stemming from the need for full disclosure of resale details to accurately determine actual profits. Additionally, it fails to account for factors such as currency fluctuations, inflation, and the inherent difficulty of verifying previous valuations.

As noted by Fabiana Nascimento, Director of Visual Arts at AUTVIS (Associação Brasileira dos Direitos de Autores Visuais), “[t]he Artist’s Resale Right in Brazil was recognized in 1981 […] [but] it has been very difficult to apply […], as it defines the charge through the difference in values (prices) between the sales of the work, which in a country that has had six currency changes in the last 50 years is practically impossible”. Similarly, the Chilean ARR legislation is currently being amended due to its practical inconveniences.

Moreover, when determining the rate, it is also important to consider the establishment of caps or thresholds as a condition to recognize the right, as in the European Union. However, in Latin America, discussions about caps have been limited for two primary reasons. Firstly, many local art markets are still maturing and have yet to see the astronomical sales common in Europe or the United States. Indeed, while one of the most expensive sales in Latin America was Paisaje de calicanto azules (1932) by Olga de Amaral, which sold for USD 225,633.47 in 2021 at BogotaAuctions, Klimt’s Lady with a Fan (1917–18) fetched USD 108.4 million at Sotheby’s London in 2023.

Secondly, laws in Latin American countries, following a continental approach of droit d’auteur, tend to be strongly pro-artist, at least in principle. As a result, establishing a minimum economic threshold for recognizing this right may be perceived as unfair, as it could undermine the acknowledgment of an author’s rights regardless of the associated administrative costs for art market professionals (AMPs). Essentially, the right should be upheld for artists irrespective of the burden on these professionals, ensuring that even modest or minimal royalties are duly paid.

Although caps and thresholds might help protect the market, interviews with European CMOs indicate that the current rate structure, unchanged since 2001, requires revision. For instance, ADAGP (Société des Auteurs dans les Arts Graphiques et Plastiques) notes that the existing cap may not align with today’s record art prices, potentially limiting artists’ earnings from high-value sales. Likewise, DACS (Design and Artists Copyright Society) emphasizes that while the initial minimum threshold might have been justified when the regulation was introduced, administrative costs have since decreased, resulting in the exclusion of many artists and diminishing the overall impact of the right.

B. Administration of ARR: Individual, Collective, or Mandatory?

Similarly to the rate of ARR, Article 14ter provides no specific guidelines on the administration of the right, leaving national legislators a range of options. Thus, administration may be conducted by the author and/or a CMO on either a voluntary or mandatory basis.

Notably, collective management is often regarded as the more efficient mechanism for administering the right, and in countries that successfully implement ARR, CMOs play a pivotal role. However, in Latin America, only 35% of countries have established CMOs, leaving the remaining 65% to individual management—with all the associated difficulties this implies for artists in collecting the royalty.

In countries where CMOs exist, ARR collection can still be challenging due to unregulated rates and unclear collection and distribution processes. For instance, in Brazil (AUTVIS), Chile (CREAIMAGEN) and Argentina (SAVA—Sociedad de Artistas Visuales Argentinos), ARR collection remains largely underdeveloped despite many efforts by these organizations to regulate or amend existing ARR regulations. Regarding other CMOs, there is insufficient information about their functioning and awareness of ARR, such is the case of Ecuador (ARTEGESTIÓN) and Peru (APSAV—Asociación Peruana de Artistas Visuales).

In most cases, collective management is voluntary regardless of the establishment of CMOs, as is the case in Uruguay. In other countries, legislation states that collective management is not compulsory, allowing authors the autonomy to manage their rights directly or through CMOs. Such is the case of Colombia, where the Constitutional Court has expressly ruled out mandatory collective management. Despite this, CMOs remain the only mechanism to grant the collection of ARR in international sales due to sister societies.

Lastly, Venezuela is the sole country with legislation that mandates collective management, yet its CMO, AUTOARTE, has ceased operations. Thus, without an active CMO, such regulation loses any practical application in favor of the artists.

C. A Successful Case: Uruguay and Prospects for Mexico

There is, however, a beacon of hope. Uruguay stands out for its effective enforcement of ARR. Although the country first adopted the right in early 1937, the regulation was amended in 2003 to introduce a 3% fixed rate on resale prices—an approach that has since yielded meaningful results.

Today, Uruguayan artists may collect individually or through AGADU (Asociación General de Autores del Uruguay), which manages ARR on behalf of APEU (Asociación de Pintores y Escultores del Uruguay) members. In addition, AGADU’s efforts have resulted in robust enforcement and public awareness of the right. Furthermore, two court rulings have consistently reinforced the relevance of ARR by reaffirming the auctioneer’s obligation to pay the resale royalties.

To ensure compliance, Uruguayan legislation established a duty for AMPs to notify resales. While AGADU actively requests resale information and even attends auctions to verify sales, compliance among dealers and galleries still largely depends on truthful declarations, making enforcement more challenging compared to auctioneers. Despite these practical challenges, effective regulation is in place, and last year, over EUR 50,000 were collected in ARR royalties, becoming a significant source of income for artists.

Meanwhile, in January 2023, Mexico formally set the tariffs for ARR collection without objections after a public consultation. While it is still too early to assess its impact, Mexico, as one of the major art markets in Latin America, could potentially initiate discussions about balancing administrative costs for AMPs.

III. Looking Ahead

The growth of Latin America’s art market presents a unique opportunity to discuss the implementation—and perhaps even the harmonization—of the resale right. While most countries in the region have adopted the right, effective implementation remains rare.

Countries exploring its regulation, however, can learn from Uruguay’s model. A straightforward regulatory framework with a fixed rate, robust collective management, and institutional support can help provide adequate protection for visual artists. By creating effective mechanisms to collect royalties and report resale information, it is possible to enhance the capacity to monitor transactions and enforce compliance in a market often characterized by informality and secrecy.

In the meantime, supporting the establishment of CMOs in the region, although not mandatory, will be crucial to facilitate the collection in international sales. Additionally, further research into local art markets could provide valuable data for legislators, CMOs, and other stakeholders to refine regulatory measures. Lastly, raising awareness among AMPs about the importance of the resale right for artists will be crucial for fostering compliance and strengthening transparency within the art ecosystem.

It is time for Latin America to address the effective regulation of ARR. By closing these gaps, Latin American countries can ensure visual artists benefit from the enduring success of their works in the international market, promote transparency in art-market practices, and align regional intellectual property rights with global standards.

Laura Villarraga Albino is a Lawyer and Art Historian with a Master’s in Intellectual Property Law from the University of the Andes (Colombia) and an LLM in Art, Business, and Law from Queen Mary University of London. She currently provides legal counsel to creators, designers and art market participants. Her research focuses on the Artist’s Resale Right and actively promotes its regulation in Latin America.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

*Anna Pedrajas

As UN Secretary-General António Guterres addressed the UN General Assembly in September 2021: “We are on the edge of an abyss.” This powerful metaphor expresses the entire depth of the climate crisis: It is now undeniable that the society we have always known will change completely because of climate change. Amid the numerous consequences stands out the certain loss of cultural heritage. Unfortunately, as climate change intensifies, the international community’s capacity to safeguard its cultural assets appears negligible.

There is no doubt that protecting heritage is a daunting task, as the notion covers a large array of elements. An independent expert in the field of cultural rights, Farida Shaheed defined cultural heritage as “the resources enabling the cultural identification and development processes of individuals and groups, which they, implicitly or explicitly, wish to transmit to future generations.” Moreover, it is intricately linked to its environment and, therefore, indirectly threatened by the dangers looming over it. Climate change is thus dangerously testing its ability to withstand the passage of time.

Protecting cultural heritage in this context may sound like a lost cause. Everyone is a contributor to the phenomenon, and no place in the world will be spared. In that sense, it is an absolute planetary issue and has been defined as a “wicked problem,” and we are now fully conscious of its consequences for cultural heritage. From Venice to the artistic living practices of Pacific islanders, the examples are countless. Its survival thus directly depends on global action.

The current situation is far from encouraging, revealing both an ambition and an implementation gap. This calls for an analysis of international law’s capacity to grasp this issue.

The Inadequacy of Cultural Heritage and Environmental Law in the Climate Crisis

The study of international norms applicable to tackling the issue, such as international environmental law agreements, treaties on cultural heritage protection, or customary rules on prevention of environmental harm, leaves us with a nuanced picture.

First, international cultural heritage law is an incomplete framework. To this day, there is no overarching obligation upholding a general duty to protect all cultural assets without distinction and at all times; the approach could rather be defined as a piecemeal one, with several instruments tackling specific aspects of heritage. Not only do they rely on a selective listing approach, but also their processes are dominated by states parties and do not offer specific, binding obligations regarding climate change.

Since human cultural heritage is embedded in its natural environment, it benefits from its legal protection in international environmental law. Not only are states bound by a customary duty not to cause transboundary harm, but sectoral environmental agreements – such as the Paris Agreement, the UNCLOS, the UNCCD, and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands also imply obligations. However, international environmental law also has its share of shortcomings: It leaves discretion to states, is not complemented by strong enforcement mechanisms, and has no overarching instrument upholding a general duty of protection. It is criticized for its poor record in effectively safeguarding the environment.

International Human Rights Law’s Contribution to the Safeguarding of Cultural Heritage amid Global Change

Thankfully, international law also presents frameworks that could be more successful in addressing cultural heritage issues in the face of climate change. Such is the potential contribution of human rights law. Indeed, it offers a wide range of tools and mechanisms that lay a strong base of duties for states and can be used directly by individuals to denounce abuses and claim reparations. The essence of international human rights law lies in an obligation for states to protect human rights, notably cultural ones, on their national territory. Thus, it establishes itself as a much-needed complement to agreements limiting themselves to horizontal obligations between states and could reinforce cultural heritage protection in the face of climate change.

Even if there is not, to this day, a clear standalone right to cultural heritage in international law, several others can tackle cultural assets and safeguard cultural diversity. These conventions require states to adopt measures to ensure respect, protection, and realization of human rights in their domestic order, lay clear duties, and offer mechanisms to seek redress in case of violation.

The most fundamental provision for our study would be Article 15 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which affirms the universal right to take part in cultural life. Since it does not differentiate between cultural assets and calls for global protection, it is a crucial legal tool to effectively advance the safeguarding of culture in the face of climate change. It is reinforced by regional instruments that also lay obligations in the matter and establish strong enforcement mechanisms, such as the Inter-American and African human rights systems.

Besides, some cultural assets benefit from specific, additional protections. For instance, Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights focuses on the culture of minorities, while Article 31 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples affirms the protection of their cultural heritage and expressions.

Other human rights can contribute to the safeguarding of culture. We can consider, for instance, religious rights, the right to self-determination, or the right to a healthy environment. Even if it is only binding at the regional level to this day, the latter gives a basis for global protection of the environment, its components, and, therefore, the human society that depends on them.

Thus, thanks to systemic integration, which has led to the climatization of human rights law, victims of climate change can defend their interests and demand more ambitious climate action. This strategic use of human rights provisions on culture to advance climate action and obtain climate justice for cultural assets keeps proving itself to be a promising legal avenue. Recent developments, such as two distinct decisions from the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee on the Rights of the Child, in the same context of harmful mining activities denounced by Sami populations in Finland, corroborate that judicial and quasi-judicial powers may help serve the protection of cultural rights. This argument has been accepted in the context of climate change, as the Torres Islands petition in front of the Human Rights Committee confirmed. As it has been suggested, cultural rights might be a more adequate tool than other international norms and other human rights to advance climate action and could be used to carry out strategic litigation. Other cases could draw inspiration from these precedents and arise in the future. Recent developments at the domestic level, such as the Bonaire case in Dutch courts, confirm this potential. But additional elements indicate that culture will not be safeguarded through the courts alone.

Human Rights Litigation’s Unfortunate Shortcomings in Protecting Cultural Heritage

Even if it has the potential to realize climate justice, human rights litigation is not immune to hurdles and will not be a panacea.

First, there are shortcomings directly imputable to the international legal order. Whereas human rights litigation depends on the ratification of instruments and the acceptance of human rights bodies’ jurisdiction, decades of practice reveal that its contribution should be relativized due to reluctance to implement judicial decisions.

Domestic litigation also faces its hurdles. Seeking climate obligations and reparations requires grasping complex questions of causation that courts will not be the most legitimate authorities to solve, and adequately repairing this noneconomic damage will be a thorny issue. Judges have also been cautious not to overstep their functions and instead leave freedom for states to implement decisions and remedy harm. The recent European Court of Human Rights’s decision, KlimaSeniorinnen v. Switzerland, is a powerful example of such restraint.

More generally, human rights law presents its share of conceptual difficulties. There exists a divergence of views between human rights bodies on the idea of extraterritorial application of conventions. Even if the Inter-American Court, in its 2017 advisory opinion, affirmed a duty to prevent environmental harm to avoid causing human rights harms to populations abroad, and found support in the Committee on the Rights of the Child, this revolutionary position in favor of a broader conception of transboundary dynamics was not shared by the European Court in its recent decision. Thus, due to these nuanced positions on “diagonal” complaints directed toward a state by foreign individuals, the possibility of getting redress for harm might appear uneven.

Finally, there are practical issues as well, such as the costs of human rights litigation and the magnitude of the compensation that is owed.

It appears that litigation will not suffice to protect cultural assets in the face of climate change, and that actions are needed beyond the courtroom. For these reasons, it is essential to view litigation as a tool to bolster climate negotiations.

Completing Climate Justice: Potential Legal Developments in Favor of Cultural Rights

Since everything is interconnected, the most specific action can contribute to a bigger purpose. Through a trickle-down effect, we can guarantee the conservation of culture by spurring environmental and climate action more generally, or by integrating it into other regimes.

Invoking human rights obligations linked to culture would be an effective way to advocate for normative improvements. Relying on human rights obligations, such as the obligation to cooperate, could be an impetus for states to negotiate new instruments in order to advance the protection of cultural assets. For instance, one could consider acknowledging that human expressions are inextricable from their environment, possibly through reference to biocultural rights.

Besides, it is essential to take the “humanization” of climate change law one step further, and require states to integrate human rights into their nationally determined contributions and report on the subject.

Developments may also be called for to overcome the verticality paradigm in the field of human rights law. Some have called, for instance, for a responsibility of repairing harm caused to foreign populations. Such a progressive interpretation of human rights instruments could turn out to be an essential aspect of addressing climate change harm, especially with regard to cultural losses.

Finally, the protection of culture will depend on the international community’s ability to rethink its governance of global issues. Proclaiming a general environmental duty through a universal human right to a healthy environment would ensure holistic protection, and answering the call for solidarity in international law by spurring cosmopolitan and intergenerational justice would contribute to safeguarding not only cultural heritage, but the climate as well.

Conclusion

Cultural heritage protection might sound like a drop in the ocean of climate justice, but it may actually go a long way in protecting the climate. Normative development in favor of cultural assets would contribute to global environmental protection. Thus, the quest for cultural rights justice can be a powerful tool to tackle climate change and strengthen global governance.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Gunna Freivalde*

I. Introduction

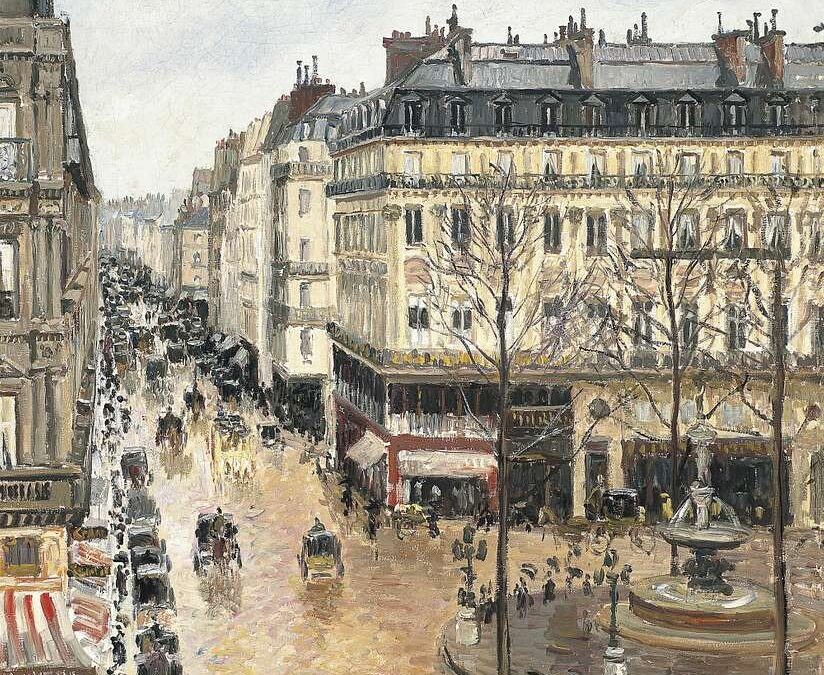

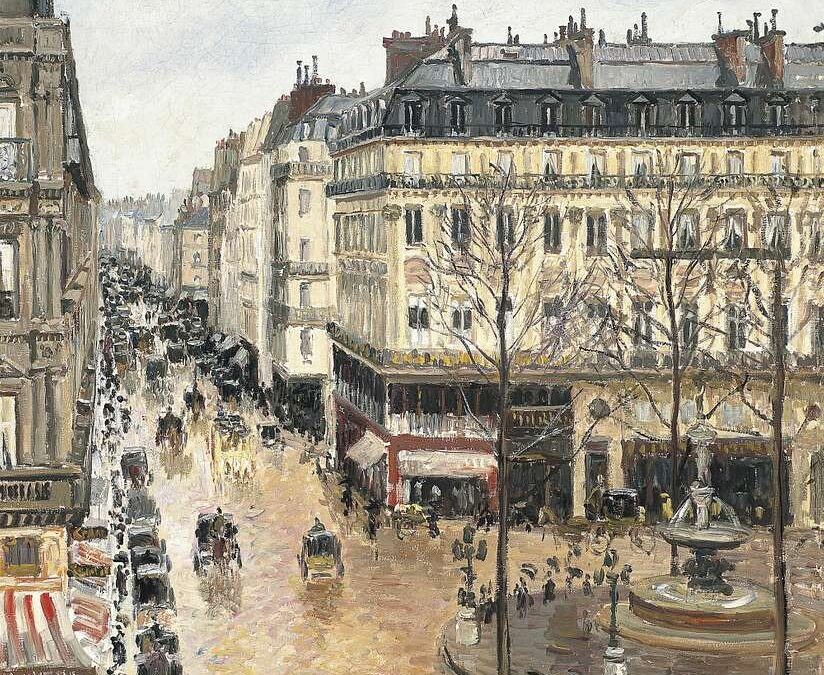

The legal struggle regarding Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré apres-midi, effet de pluie (1897) illustrates the striking relationship between legal structures and moral obligations in art restitution. Originally owned by Lilly Cassirer Neubauer, a Jewish collector, who sold the painting under duress to evade Nazi persecution in 1939, this artwork has become a central topic for debates concerning ownership, justice, and, moreover, ethical implications of owning art with such a troubled history. These implications extend to the responsibilities of current possessors, who must not only acknowledge the artwork’s past but also maintain a moral duty to respect the full picture of its provenance, particularly when that provenance involves historical injustices.

The painting ultimately found its current home in Spain’s Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection in Madrid. The Cassirer family had sought its return through California courts under the U.S. Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), claiming that their ancestor’s sale was coerced and, therefore, invalid under international law. However, lower courts applied Spanish law, which emphasizes long-term possession over claims of stolen property. This legal dichotomy has not only raised fundamental questions about the sufficiency of existing restitution laws globally but also whether they effectively address historical wrongs. As nations grapple with their colonial pasts and wartime looting, this case highlights the question of how effectively legal systems can reconcile the moral obligation to restore rightful ownership to the owners or their descendants. Ultimately, the resolution of this dispute not only affected the fate of a single masterpiece but also set precedents that will potentially influence future cases involving looted art worldwide.

Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré is not merely a work of art; it embodies a complex historical narrative that reflects the broader socio-political upheaval of its time. Painted in 1897, this piece captures the essence of Parisian life during a period marked by rapid urbanization and cultural transformation. However, its significance extends far beyond its aesthetic qualities. The painting became emblematic of the tragic consequences faced by Jewish collectors during World War II when many artworks were forcibly sold or stolen under duress from their rightful owners. Neubauer’s forced sale of the painting in 1939 reflects the systemic targeting of Jewish collectors during the Nazi era when widespread looting deprived countless individuals of their cultural heritage. The coerced nature of these transactions often left victims and their descendants without legal recourse, a legacy that persists in restitution claims today. As such, this particular artwork serves as a poignant reminder of these injustices and raises critical questions about ownership rights in cases where artworks were acquired through coercion or theft. The subsequent journey of this painting—from Cassirer’s possession to its current home in Spain’s Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection—underscores how legal frameworks often struggle to address moral imperatives associated with historical wrongs and how artworks looted or sold under duress frequently end up in private or institutional collections, often without rigorous provenance checks. These provenance checks are essentially the history of ownership and transfer of an artwork. They are intended to trace an artwork’s story back through time, verifying its rightful ownership at each stage; however, many artworks looted or sold under coercive circumstances have slipped into private or institutional collections without any scrutiny applied before their purchase. This situation is further complicated by the fact that the laws that govern such matters do not always align with ethical considerations. Although many advocate for restitution, the path forward remains fraught with challenges.

As descendants, such as those from the Cassirer family, pursue justice through contemporary legal channels, they confront not only national laws but also international norms concerning property rights and restitution. This case, in particular, exemplifies how historical context shapes contemporary discussions on art ownership; it shows ongoing tensions between legal entitlements based on possession versus ethical considerations rooted in justice for victims of past atrocities. Although understanding this historical backdrop is crucial for evaluating the legitimacy of claims made regarding Pissarro’s masterpiece today, some may overlook its significance because of present-day complexities.

II. Legal Frameworks in Art Restitution

The legal frameworks that govern art restitution are often multifaceted and conflict with moral imperatives surrounding the return of looted artworks.

Historical cases like Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), resolved by Austria returning the painting to Maria Altmann following a U.S. Supreme Court ruling (Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677, 2004), illustrate how international claims can prevail when moral imperatives align with legal frameworks. Similarly, the Gurlitt Trove revealed systemic gaps in provenance checks, prompting Germany to establish the Advisory Commission for Nazi-looted art. These cases highlight that restitution efforts often rely on the willingness of courts and nations to confront historical injustices. However, this confrontation can be deeply uncomfortable, requiring a country to acknowledge past wrongs and possibly destabilize already established stories. It may explain the lack of responses in similar cases, as the political and social costs of acknowledging and rectifying past injustices are considered too high.

In the case of Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré, this tension is exemplified because the Cassirer family was seeking to reclaim a painting sold under duress during Nazi persecution. The central legal question in this case revolved around which jurisdiction’s laws should apply: California law, which would favor claims of stolen property, or Spanish law, which would emphasize long-term possession.

Under Spanish law, Article 1955 of the Civil Code grants ownership through uninterrupted possession in good faith for over six years. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection relied on this principle, asserting that the foundation had acquired the painting without any knowledge of its tainted provenance. Spanish courts have historically favored stability in property rights, prioritizing long-term possession over historical claims.

In contrast, U.S. law, as applied under the FSIA, follows a discovery-based statute of limitations. This approach allows claimants to pursue stolen property within six years of discovery and assert rightful ownership. The Cassirer family’s argument rested on the notion that the 1939 sale was a coerced transaction, invalid under international norms recognizing the duress imposed during the Nazi era.

Ultimately, U.S. courts ruled in favor of Spanish laws, citing the primacy of Spanish law over the restitution principles underlying the Cassirer family’s claim. The decision reflects a broader issue within the realm of conflicting national laws and inadequacies of existing legal frameworks in addressing cases that are morally compelling yet legally complex. By applying the lex situs principle, U.S. courts effectively sidelined ethical considerations related to Nazi-looted art. Although some may see the ruling as justified, it invites a deeper analysis of the intersection between morality and legality, challenging established norms in the process.

The application of Spanish law’s “good faith acquisition” principle seemingly legitimizes transactions conducted under dubious circumstances during a period marked by widespread looting. Although there exists a moral imperative to restore stolen artworks to their rightful owners or heirs, such principles often clash with established legal doctrines that prioritize local laws over historical injustices. The Pissarro case exemplifies this tension—while there is a clear moral argument for restitution based on the painting’s Nazi provenance, legal frameworks fail to provide adequate mechanisms for redress when confronted with competing national interests. This ruling shows not only a failure of individual claims but also highlights systemic deficiencies within international art restitution practices.

Furthermore, international treaties and agreements related to cultural heritage and restitution have been established; however, they often lack enforceability or widespread adherence.

Adopted in 1998, the Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art emphasizes the need for “just and fair solutions” in restitution claims. However, these principles lack binding legal force, leaving their implementation to the discretion of individual states. The Pissarro case highlights the inadequacy of voluntary guidelines in resolving complex disputes. The 1970 UNESCO Convention aims to combat illicit trafficking in cultural property but does not specifically address instances such as this case, where ownership was transferred under coercive circumstances. This means that existing legal frameworks frequently fall short of offering just resolutions for victims or their descendants because this issue remains complex and multifaceted.

The disparity between national laws and international norms creates significant barriers for claimants seeking justice, particularly in instances involving cultural heritage and restitution. This inconsistency manifests in conflicting legal frameworks that govern ownership and repatriation of artworks, and the Pissarro case exemplifies this dilemma, wherein differing national laws obstruct equitable resolution. Such inconsistencies not only complicate the adjudication process but also undermine the ethical imperatives that drive claims for stolen or looted art. A unified approach—potentially through binding international arbitration mechanisms—could provide a more effective means of addressing disputes like the Pissarro case. Binding arbitration can offer a neutral forum where diverse parties can present claims within an internationally recognized legal context.

III. Moral Implications of Art Ownership

The moral implications of art ownership, particularly in cases involving looted or coerced sales, challenge our understanding of property rights and ethical responsibilities. In the case of Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré, the painting’s journey from Neubauer to its current location in Madrid in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection raises profound questions about the legitimacy of ownership acquired under duress. Museums bear a moral obligation to conduct thorough provenance research, particularly for artworks that may be linked to looting or coercion. The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection’s retention of the artwork in question has drawn criticism, highlighting the ethical challenges faced by institutions that prioritize possession over restitution.

The ethical precedent set by Austria’s restitution of Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I demonstrates how returning looted art not only rectifies historical wrongs but also restores trust in cultural institutions. Similarly, the Gurlitt Trove underscored the importance of transparency and provenance research in fostering public accountability.

Art is not merely a commodity—it embodies cultural heritage and personal history. When artworks are acquired through coercion or theft, as was the case for many Jewish collectors during World War II, ownership becomes ethically contentious. The Cassirer family’s pursuit reflects broader societal values advocating for restitution, aligning with the Washington Principles’ emphasis on “just and fair solutions.” Their claim rests on the assertion that the sale was not a legitimate transaction but rather an act forced upon Neubauer by an oppressive regime—an argument that challenges conventional notions of property rights. The argument not only calls into question the legitimacy of transactions conducted under oppressive conditions—acknowledging that some property rights may be invalidated because their origins are rooted in duress—but also compels a reassessment of the understanding of justice and equity within legal frameworks. Furthermore, this dispute underscores broader societal values regarding justice and accountability as there is a growing recognition that returning looted art is not merely a matter of legal compliance but also one of rectifying historical wrongs. The debate surrounding Rue Saint-Honoré shows how unresolved issues from the past continue to influence contemporary discussions on ownership and restitution.

Once again, we can ask ourselves: should possession alone determine rightful ownership? Many argue that artworks obtained through coercive means should be returned to their original owners or their descendants as a matter of moral duty—an essential step toward acknowledging past atrocities. This perspective aligns with international norms advocating for justice over mere legality; however, it often clashes with national laws, such as the Spanish laws prioritizing long-term possession. Ultimately, resolving disputes like the one over Pissarro’s painting requires not only navigating complex legal landscapes but also engaging deeply with ethical considerations rooted in historical injustices.

IV. International Disparities in Restitution Laws

Disparate national laws complicate restitution efforts. The Gurlitt Trove and Altmann’s legal battle illustrates just how proactive measures, such as provenance research and transparent judicial processes, can bridge gaps in restitution laws. These cases should serve as blueprints for addressing complex claims, such as the Cassirer dispute.

In different European nations, laws regarding art restitution frequently prioritize the rights of current possessors over those asserting historical injustices. In this case, Spain’s legal framework permits the retention of artworks acquired through prolonged possession, even when such acquisitions occurred under morally questionable circumstances. This contrasts sharply with some jurisdictions that have enacted specific legislation aimed at facilitating the return of looted art to its rightful owners or their descendants. Such disparities create an uneven playing field.

Furthermore, international treaties addressing cultural heritage often lack enforceability or fail to adequately cover cases similar to that of Pissarro’s painting. Consequently, in such cases, the claimants encounter significant obstacles when they pursue justice across borders. This, in turn, underscores the need for a more unified international approach to address historical wrongs effectively, even if it requires a commitment from nations worldwide to prioritize ethical considerations alongside legal entitlements in matters pertaining to looted art.

The case regarding Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré showcases the profound tensions that exist between legal frameworks and moral imperatives in art restitution. The painting’s journey from its original owner to its current place underscores a broader dialogue about ownership rights rooted in coercion versus those grounded in prolonged possession. This dispute reveals significant disparities in international restitution laws and highlights how different jurisdictions prioritize stability over rectifying past wrongs. Although the legal path appears convoluted, this pursuit remains essential because it challenges the status quo.

The moral implications of such ownership claims extend beyond individual artworks; they challenge societies to reckon with their histories and acknowledge the consequences of past wrongdoings, and this case serves as a crucial reminder that legal entitlements cannot exist in a vacuum devoid of ethical considerations. As nations navigate these complex landscapes, it becomes increasingly clear that a unified approach is necessary—one that prioritizes justice and accountability alongside adherence to statutory frameworks. Ultimately, this case is setting important precedents for future disputes involving the restitution of art worldwide. Achieving a balance between legal norms and moral obligations is essential for fostering an environment where such matters can be addressed meaningfully; however, paving the way for restorative justice within the realm of cultural heritage remains a challenging endeavor because it requires navigating deeply entrenched interests.

V. Conclusion

The implications of this case extend beyond mere legal technicalities—they engage with broader societal values regarding justice and accountability in light of historical wrongdoings. In this particular case, the act of restitution transcends mere financial compensation or the transfer of the artwork—it embodies an acknowledgment of loss suffered during one of history’s darkest times. Although many may agree on the necessity of restitution, the complexities involved cannot be overlooked and require careful consideration and understanding. Camille Pissarro’s Rue Saint-Honoré serves not only as an invaluable artistic treasure but also as a symbol of contemporary struggles over justice within art restitution discourse.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Chad Patrick Osorio*

I. Introduction

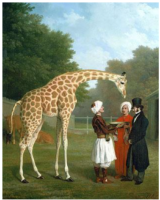

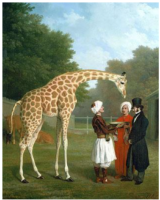

The intersection of art and wildlife conservation raises critical questions about the role of cultural expression in addressing environmental challenges. Art has historically depicted nature and human-wildlife interaction, illustrating the connection between humans and the natural world. It has also, however, inadvertently contributed to the illegal wildlife trade (IWT), particularly when art has increased the social acceptability and desirability of owning and hunting wildlife. Examples include Leonardo da Vinci’s The Lady with an Ermine (c. 1489–1490), Peter Paul Ruben’s The Tiger Hunt (c. 1615–1616), and Jacques-Laurent Agasse’s The Nubian Giraffe (c. 1767–1849). Additionally, wildlife products have been used in the creation of art, including plant and animal dyes for paintings and textiles, as well as wood, bone, and horns for ornamentation, trinkets, and sculptures. Both examples are evident in the artistic traditions of Southeast Asia.

(Images are provided by the author)

Southeast Asian art, both past and present, richly incorporates depictions of and references to wildlife. Examples of this include illustrations from Thai horoscope manuals in the 1800s, an early deity carving from ivory, and an antique Balinese rosewood sculpture of a mythical beast, among many others. These artworks resonate with the region, which is home to some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems and harbors iconic species like tigers, elephants, and hornbills. These species are not only ecologically significant but also hold deep cultural value. However, this rich biodiversity is under severe threat from the illegal wildlife trade. Despite stringent international conventions such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), IWT remains a multi-billion-dollar industry and one of the most lucrative illegal activities in the world. IWT presents numerous challenges, with wide-ranging impacts that affect both the natural environment and human society. Its consequences are significant and multifaceted, spanning environmental, economic, political, and social dimensions.

Southeast Asian countries serve as crucial source, transit, and destination points for wildlife trafficking. Due to their highly porous borders, rapidly growing middle class, and deeply entrenched cultural practices, these countries face unique challenges in addressing this issue. One contributing factor to the underground wildlife market is that derivative products of flora and fauna are trafficked for use in traditional and contemporary works of art. In this article, we seek to shift this perspective and instead explore how international legal frameworks protecting art can be leveraged to protect wildlife within the regional jurisdiction of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The article is organized as follows: in Part II, we discuss specific cases of some of the most trafficked wildlife in relation to art, including elephant ivory, hornbill casques, hawksbill tortoiseshells, and rosewood and agarwood timber. We outline the current legal conservation framework in the region, giving examples under both treaty and domestic law in Part III. In Part IV, we propose how existing legal protection for art and heritage within the ASEAN can contribute to wildlife protection, capitalizing on market regulation for sustainability. We conclude, in Part V, with an ASEAN-led sustainable art certification program seeking to increase the joint value of nature in ASEAN art.

II. Art and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

The art market—both legal and illicit—has a long history of using wildlife products. Items such as ivory sculptures, mother-of-pearl inlays, and exotic leather crafts are prized for their aesthetic and cultural value. In Southeast Asia, traditional and religious art often incorporates these materials, creating tension between cultural preservation and wildlife conservation.

One of the most glaring examples of art driving wildlife exploitation is the ivory trade. Ivory, derived from the tusks of elephants, has been used for centuries in carving intricate sculptures, religious artifacts, and decorative items. Ivory carvings are highly sought after for their cultural and aesthetic value, particularly in the historical production of religious figurines. Despite the ban on the international trade of ivory, demand persists, exhibited by high ivory prices in Asia. Poachers and traffickers exploit legal loopholes, smuggling ivory to and from Southeast Asia, where artisans transform them into works of art. This demand contributes significantly to the decline of elephant populations, particularly the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus spp.), which is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Another example is the use of helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) casques in jewelry and ornamental art. Known as “red ivory,” the solid keratin casques are carved into intricate designs that are highly valued in East and Southeast Asia. The helmeted hornbill, native to Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand, faces critical endangerment due to poaching driven by demand for its casques. The species plays a vital ecological role as a seed disperser, and its loss has cascading effects on forest ecosystems. Despite international protections, the helmeted hornbill continues to be targeted, with traffickers smuggling casques through clandestine networks.

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), classified as critically endangered, is another species victimized by the art market. Its tortoiseshell is used to craft jewelry, combs, and decorative items. In the Philippines, tortoiseshell crafts have a long tradition, particularly in coastal communities. The exploitation of hawksbill turtles for art not only threatens their survival but also disrupts marine ecosystems, where they play a role in maintaining coral reef health. The continued demand for tortoiseshells highlights the need for stronger enforcement.

Plants also play a significant role in the illegal trade linked to art. Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.), prized for its deep red hue and durability, is commonly used in furniture and carvings. Rosewood smuggling is a pervasive issue in countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, where forests are stripped of this valuable resource to meet international demand. The exploitation of rosewood for luxury goods has led to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and illegal logging operations that endanger local communities. Similarly, agarwood (Aquilaria spp.), used in perfumes, incense, and intricate carvings, is overharvested due to its high market value. Native to several ASEAN countries, agarwood trees are now critically endangered in many areas, further threatening forest ecosystems.

These are just some examples of wild flora and fauna, from land, sea, and air, trafficked within Southeast Asia to serve the global demand for art.

III. Legal Frameworks Protecting Wildlife in ASEAN

There are existing legal protections for wildlife in Southeast Asia, led foremost by ASEAN—a regional intergovernmental organization that promotes political and economic cooperation among ten Southeast Asian countries. Founded on August 8, 1967, through the signing of the ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, ASEAN has since grown to include Brunei Darussalam (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos (1997), Myanmar (1997), and Cambodia (1999). ASEAN’s core objectives are to foster regional peace and stability, stimulate economic growth and prosperity, and enhance cooperation among its Member States.

ASEAN places much emphasis on principles such as mutual respect, non-interference, consensus-building, and collaboration. The regional body seeks to ensure that Member States acknowledge each other’s sovereignty and refrain from actions that could undermine national interests or be perceived as external intervention in domestic affairs. Consensus-building is equally central to ASEAN’s decision-making process, requiring unanimous agreement among its members, which ASEAN implements through regular meetings and consultations. Through this cooperative political-legal framework, the regional organization has developed various policies and programs to promote interstate cooperation in trade and investment, regional security, social and cultural matters, and sustainable development. Among its notable accomplishments is the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which seeks to create a unified market and production base, enabling the free movement of goods, services, investments, and skilled labor within the region. As a result of these efforts, as of 2022, ASEAN has emerged as the fifth-largest economy globally.

ASEAN countries are signatories to various international conventions aimed at curbing illegal wildlife trade. The most significant is CITES, which regulates the international trade of endangered species. This is supported by regional initiatives like the ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN), which facilitates cooperation among Member States to combat wildlife trafficking, providing a platform for sharing intelligence and best practices among enforcement agencies. Similarly, the ASEAN Working Group on CITES and Wildlife Enforcement aligns Member States with CITES requirements and enhances enforcement capabilities.

Each ASEAN country has its own set of laws addressing wildlife conservation and illegal trade. For instance, Thailand’s Wildlife Conservation and Protection Act (2019) criminalizes the possession and trade of protected species and their derivatives. Indonesia’s Law on Conservation of Biological Natural Resources and their Ecosystems (1990), recently updated, includes provisions for wildlife trafficking, imposing penalties for trading endangered species. In the Philippines, the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act (2001) prohibits the exploitation of endangered species for commercial purposes. Despite these frameworks, enforcement challenges persist, including corruption, lack of resources, and inadequate cross-border collaboration. Below is the table of domestic legislation in support of wildlife protection in the ASEAN region.

Table 1. CITES-related Laws in ASEAN Countries

IV. Exploring Legal Synergy between Art and Conservation Law

The question remains: how can art law support these wildlife conservation initiatives? After all, art law is a specialized legal field addressing the creation, ownership, sale, and protection of art, encompassing intellectual property rights, cultural heritage preservation, provenance verification, and market regulation. Nature conservation law, on the other hand, focuses on safeguarding natural resources, biodiversity, and ecosystems, regulating activities like hunting, fishing, logging, and trade to prevent environmental degradation. In this section, we explore how integrating these two domains can offer a promising tool to address the use of wildlife products in art, particularly in the ASEAN region.

One potential initiative involves merging intellectual property protection with eco-labeling certifications. Geographical indications (GIs), which identify products with qualities tied to their origin, could be expanded to certify products as sustainably sourced and wildlife-friendly. This approach, in line with the One Village, One Product campaign led by ASEAN, could protect sustainable wildlife use while fostering community-based practices. This strategy unites conservation, intellectual property, and cultural heritage for a common cause.

As envisioned, the enhanced GI certification would include sustainability and wildlife-friendly practices as core criteria. Commercially available art and heritage products such as textiles, wood carvings, and agricultural goods would need to meet these standards to earn the ASEAN-approved label. This certification scheme would offer significant benefits for wildlife protection. Encouraging alternative sustainable materials and ethical production practices decreases reliance on resources derived from endangered species. The overexploitation of high-value wood carvings could be curtailed through the certification of sustainably sourced wood. Additionally, discouraging the use of endangered wildlife derivatives such as ivory or hornbill casques at the grassroots level supports supply-induced demand reduction of these illegal products.

Moreover, the scheme uplifts community-based approaches by linking sustainability to products deeply rooted in local traditions and indigenous knowledge. Many GI art products reflect cultural identity and heritage. By adopting eco-focused practices and providing government support for alternative wildlife-friendly materials, artisans can act as stewards of both cultural and natural resources, preserving their traditions while supporting conservation. Artisans and woodworkers across the region can integrate sustainable sourcing without compromising their craft’s authenticity. Capacity-building initiatives, such as training artisans on sustainable methods, would strengthen community resilience, protect socio-economic rights, and ensure long-term benefits.

Economic incentives further bolster this approach. Certified products command higher market value, attracting ethical consumers who prioritize sustainability and conservation (a global market enjoying steady market growth). This can create a cycle where increased demand for certified products motivates communities to adopt wildlife-friendly practices, amplifying conservation impacts. At the same time, campaigns can be launched to attach stigmas to art products that are not sustainably sourced. By associating non-sustainably sourced wildlife products with negative social and ethical connotations, campaigns can discourage consumer demand and shift market preferences toward certified alternatives. Public awareness initiatives, celebrity endorsements, and policy interventions can reinforce these stigmas. This helps make unsustainable products less desirable and even socially unacceptable. Over time, such stigmatization can pressure artisans and commercial art producers to transition toward sustainable sourcing practices to maintain market credibility and consumer trust. These campaigns go hand-in-hand with labeling requirements and trade restrictions and make it easier for consumers to distinguish between ethical and unethical products.

Implementing this scheme in Southeast Asia requires careful planning and collaboration among Member States. ASEAN policymakers must set clear standards and enforcement mechanisms. Partnerships with other international bodies as well as academia can provide funding and technical expertise, while community leaders, Indigenous Peoples, and civil society can work together to adapt traditional practices to meet sustainability criteria without losing cultural authenticity.

V. Conclusion

One of the most significant challenges in the use of wildlife in art is balancing cultural preservation with conservation. Traditional art forms that rely on wildlife products must adapt to modern conservation ethics without losing their cultural significance. In line with ASEAN’s goal of a common regional market, facilitating both supply and demand for wildlife-friendly art can incentivize artisans to adopt sustainable practices and influence social norms for wildlife protection. To spearhead this, an ASEAN-led art certification program can help consumers identify and support ethical and environmentally responsible art.

Based on this premise, art law holds immense potential to support the protection of wildlife in the ASEAN region. However, this potential can only be realized through regional cooperation, an integrated legal framework, and community engagement. By aligning the art world with conservation goals, ASEAN can transform a significant challenge into an opportunity for preserving its rich biodiversity and cultural heritage.

*Chad Patrick Osorio is a current PhD Researcher at Wageningen University and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines Los Banos. He thanks Dasha Gretchikine (Wageningen University) for the editorial support and Carl Kristoffer Hugo (University of the Philippines Los Banos) for the research assistance.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

*Anne-Marie Carstens

In early 2025, the Octagon Earthworks, a 2,000-year-old indigenous ceremonial and burial site comprised of earthen geometric structures, opened to the public. The opening came after two parties—the government agency taking possession through eminent domain and the leaseholder that occupied the site—settled the last issue in their drawn-out legal dispute by agreeing on the just compensation owed for the taking. The site forms a crucial part of a collection comprising the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, which was nominated by the United States in 2022 and selected by the World Heritage Committee for inscription on the international World Heritage List. The list is the core feature of one of the world’s most popular treaties (by participation), the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (World Heritage Convention). The treaty celebrates and provides a protective framework for listed sites of “outstanding universal value,” and the World Heritage List today includes 1223 heritage sites in 168 countries. The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks became only the fourteenth cultural or mixed cultural-natural heritage site in the United States to make the list.

The litigation’s friction points nonetheless highlight lingering questions at the intersection of the Takings doctrine and international cultural heritage law. First, the case brought into question when holders of private property rights ostensibly must be ousted to satisfy the treaty’s requirements of “authenticity” and “integrity.” Second, the litigation embodied a resurgent, palpable resistance to recognizing public parks and other aesthetic objectives as a valid “public use” under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause and its state corollaries. In doing so, it offered another data point on “public use” in the post-Kelo environment.

The Octagon Earthworks Site & the Takings Controversy

According to the nomination file submitted by the United States, the Octagon Earthworks and the larger Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks complex consist of massive, geometrically shaped mounds constructed by the Hopewell culture that flourished in the Ohio River Valley as a religious movement (rather than a distinct indigenous group) from approximately 1CE to 400CE. The United States observed that the Octagon Earthworks showcase the vanished culture’s profound mathematical skill and astronomical understanding because corners of the octagonal shape “encod[e] all eight lunar standstills over an 18.6-year [lunar] cycle.” When the moon peaks at its northernmost point at the end of each lunar cycle, it “hovers within one-half of a degree of the octagon’s exact center,” making the site “a testament to indigenous sophistication.” The mounds were long known to form part of an ancient ceremonial site, but modern scholars only came to recognize them as a mathematical and cosmological marvel in the 1970s.

Ohio’s state historical organization initiated a condemnation proceeding in 2018 to take full possessory rights through eminent domain. In a twist from the usual takings action, the organization already owned the property in fee simple since 1933. But it did not possess the full idiomatic “bundle of sticks” because it had continuously leased it to the challenging party, the Moundbuilders Country Club. The litigation established that the club had operated a golf course on the mounds since 1910, initially pursuant to a lease with the city, the organization’s predecessor-in-interest. In fact, the nomination file acknowledges that the private country club was established for the express purpose of operating a golf course on the site as a cultural preservation measure. The city at the time lacked funds to create a public park to curb encroaching development and considered a golf course a viable alternative. In 1997, the historical organization renewed the club’s lease until 2078.

The club first challenged the basis for condemnation of its leasehold. Like most states in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. City of New London (2005), Ohio firmed up takings requirements under its state constitution, both through legislation and case law that judicially ratcheted down the deference owed to legislative determinations prescribing the government’s eminent domain powers. The challenge reached the state’s highest court, which ruled in State ex rel. Ohio History Connection v. Moundbuilders Country Club Co. (2022) that the historical organization could acquire full possessory rights to the “extraordinary piece of land.” The court observed that “[t]he historical, archaeological, and astronomical significance of the Octagon Earthworks is arguably equivalent to Stonehenge or Machu Picchu.” The ruling left the parties to tussle only over the measure of just compensation, which they resolved in the recent confidential settlement.

While the litigation was pending, the larger complex comprising the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks was added to the World Heritage List. Under the treaty, immovable cultural property qualifies if it possesses “outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science” or “outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view.” In addition to the primary criterion of “outstanding universal value,” cultural sites must also meet one of ten additional criteria. The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks qualified with two: representing “a masterpiece of human creative genius” and bearing “a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared.”

Private Custodians and Public Assurances of “Authenticity” and “Integrity”

According to the Ohio Supreme Court, the club asserted that it could maintain its leasehold at the Octagon Earthworks site, notwithstanding the site’s (prospective and then eventual) World Heritage status. It stressed that its leases obligated it “to preserve and maintain” the site and that it provided reasonable public access. The historical organization answered that it “could not convert the private golf course into a public park” without extinguishing the leasehold.

By all accounts, the club mostly acted as a good steward during its century-plus use, and its status as a private party was not automatically disqualifying. The World Heritage Convention does not require government control over nominated or listed properties. For example, the privately owned Guggenheim Museum comprises part of the World Heritage site celebrating the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, and several private properties are proposed for the nomination of Civil Rights Movement sites.

But the club also operated an active golf course on the site, installed paths for golf carts, and disturbed the mounds when renovating. Tensions over public access increased over time. Several mounds were off-limits to public use for much of the year, and the country club also imposed onerous restrictions that curbed use of the central part of the site. For example, the club assessed an access fee of almost $25,000 for a planned “moonrise celebration” at the site, to cover the costs of additional insurance, security, and a temporary platform to keep the public off the green. In arguing that it could coexist with the public on the site—and even making that argument the keystone of its motion for reconsideration—the club confused the ability of private property owners to maintain World Heritage sites with feasibility.

Not only was coexistence between golfers and the public infeasible, but swinging clubs, roving golf carts, and paved pathways were foreclosed by the treaty’s authenticity and integrity requirements. A nominating country must pledge to ensure the site’s authenticity and integrity, and failure to do so can lead to delisting, a draconian measure that the multinational World Heritage Committee has implemented for Liverpool and Dresden and threatened for Vienna. The treaty’s Operational Guidelines make clear that authenticity means that a site’s cultural values are expressed in attributes that include form and design, use and function, and location and setting. Integrity, on the other hand, “is a measure of the wholeness and intactness” of the site, which considers whether it suffers from development or neglect.

To this end, federal regulations provide that privately owned or controlled properties must have documented protective measures, such as real covenants that prohibit, “in perpetuity, any use that is not consistent with, or which threatens or damages the property’s universally significant values[.]” The regulations also provide that “no non-Federal property may be nominated to the World Heritage List unless its owner concurs in writing to such nomination.” New federal regulations on World Heritage nominations were proposed in December 2024 to help close gaps, including by shoring up the definition of an “owner” whose concurrence is required. The proposed regulations would limit the definition to holders in fee simple—unlike the definition of “owner” under Ohio’s eminent domain statutes, which extends to any individual or entity “having any estate, title, or interest in any real property sought to be appropriated.”

Aesthetic Takings

The club’s strenuous assertion that the taking was not “necessary” for a valid “public use” is more perplexing, even though the site’s World Heritage status was aspirational at the time of the taking and only materialized during the litigation. A government’s ability to take property through eminent domain for public parks is well-trod law, and Ohio law expressly specifies that public parks “are presumed to be public uses.” But the state’s post-Kelo legislative changes added the necessity requirement as a preamble to more specific requirements about taking blighted areas for redevelopment. The elevation of state takings standards above the federal minimum standard decoupled a long history of shared interpretation. The result may ultimately give less force to longstanding precedent for aesthetic takings for cultural heritage sites.

As far back as the late 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court made clear that takings could be used for public parks. The Court in United States v. Gettysburg Electric Railway Co. (1896), for example, extolled the virtues of eminent domain to acquire private property rights to form a historically and culturally significant site: the Gettysburg National Military Park.

In 1929, on similar facts to those here, the Court even awarded penalties for a “frivolous” appeal because the appellant had “no basis for doubting the power of the State to condemn places of unusual historical interest for the use and benefit of the public.” The case concerned the Shawnee Mission, a site of “unusual historical interest” for which the state historical society acted as custodian. The City Beautiful movement of this same era often relied on takings to replace tenements and other downtrodden urban areas with public parks and scenic areas. Such initiatives sometimes had a sinister side when they disproportionately impacted minority communities, as when an African-American neighborhood in Charlottesville was replaced with a public park containing a monument to Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. (The Jackson monument and the infamous statue to General Robert E. Lee nearby were both donated by a city benefactor in the 1920s and removed in 2021.)

Here, the club suggested that it established a higher “public use” than a less-profitable heritage site. As the Ohio Supreme Court observed, the club argued “that its positive economic impact in the community and its efforts to preserve the earthworks provided a far greater tangible benefit to the public than the hypothetical and unlikely benefit to the public that allegedly would be realized by the appropriation [if listed on the World Heritage List].” Curiously, this argument is the antithesis of the anti-Kelo resistance, which objects to Kelo’s deferential gloss on “public use” based on increased tax revenue and economic development. Indeed, counsel for the Kelo homeowners raised the opposite hypothetical in their oral argument, arguing that it would subject a church to a valid taking when it “would produce more tax revenue and jobs if it were a Costco, a shopping mall or a private office building.”

To be clear, courts so far seem poised to reject such arguments, as the state courts did here. A similar takings dispute was also settled in 2023 for a visitor center and museum near The Alamo in San Antonio, part of another World Heritage site. Congress, too, has annotated the Takings Clause by acknowledging that use of eminent domain “to establish public parks, to preserve places of historic interest, and to promote beautification has substantial precedent.” Last year, the Second Circuit upheld a city’s exercise of eminent domain even for a “passive use park,” an unimproved tract acquired to prevent the construction of a so-called “big-box” store. The lawsuit, in which the challengers were represented by the same legal counsel as the challenging litigants in Kelo, may be destined for the U.S. Supreme Court.

Even if heightened state standards for takings start to chip away at parks more generally, a World Heritage site’s recognized “outstanding universal value” should affirm a government’s right to flex its eminent domain power. As the court said about the Octagon Earthworks, “This is not just any green space. It is a prehistoric monument that has no parallel in the world in its ‘combination of scale, geometric accuracy, and precision.’” Now the public can visit a cultural heritage site that joins the impressive company of the best-known World Heritage cultural sites worldwide, including the Great Wall, Machu Picchu, the Taj Mahal, Vatican City, Rapa Nui, and Stonehenge.

*Anne-Marie Carstens, JD, DPhil, is Associate Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore School of Law and Senior Fellow at the Center for International and Comparative Law (CICL). She has written extensively in the fields of public international law, property law, and cultural heritage law, including as co-editor of a book and author of several book chapters and articles.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Daniel Ricardo Quiroga-Villamarín*

In the collective imagination of international lawyers and scholars of international affairs alike, perhaps the most vivid image we have of Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” might be of its absence. While a tapestry reproduction of this famous artwork has adorned the entrance to the Chamber of the United Nations Security Council since September 13 1985, it was briefly “covered up” in February 2003. The reason was that Colin L. Powell, then Secretary of State of the U.S., delivered an infamous speech before the United Nations Security Council on Iraq’s failure to disarm —leading, eventually, to the so-called Second Gulf War later the same year. Instead, a blue curtain with the emblem of the United Nations was conspicuously hung. And, from a specific angle, TV cameras were able to capture a dismembered “horse’s hindquarters […] just above the face of the speaker.” While there is no public record of the decision-making behind this aesthetical choice, journalists have long speculated that it “would be too harrowing, too politically pointed if Colin Powell were to be shown defending war in front of this great denunciation of war” (see also here). Be that as it may, this minor incident bears witness to the entanglements of art, war, and law in our unending quest to create a just international order.

This quest, of course, began long before the establishment of the United Nations in 1945 —and even perhaps of its immediate predecessor institution, the League of Nations (thereafter, the League), in the wake of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20. With this in mind, in this short intervention, I trace the connections between the Spanish Civil War of 1936 (the conflict which originally inspired Picasso’s work) and the League, all the way to the current challenges our liberal rules-based international order (with the United Nations as its cornerstone) is facing, using the many lives of the “Guernica” as a running thread. For the horrors that once inspired Picasso’s century continue to haunt our times —in fact, they seem to be returning with a vengeance on the world stage.

The entrance to the Chamber of the League’s Council (which, in many ways, worked as the inspiration of our contemporary Security Council) also has a connection with the Spanish polity. As I’ve explained with more detail elsewhere, all its interior décor had been donated by the Second Spanish Republic in the mid-1930s. This included the Latin-inscribed heavy bronze doors that guarded the entrance to the League. But the centerpiece of the Spanish donation had been the mural “The Lesson of Salamanca,” painted by the Spanish —or Catalan, depending on who you ask!— artist José María Sert y Badia between 1934 and 1936. This image was affixed to the Chamber’s abode, and it towered over the delegates who sat in its semicircular table. To accompany it, Sert also created a series of smaller murals for the walls entitled “Hope and Justice,” “Social Progress and the Law,” “The Vanquished and the Victors,” and “Peace Revived and Peace Dead.” The result was what in German is known as a Gesamtkunstwerk: a “total work of art”: an overarching aesthetical structure that gave the Council’s Chamber a coherent identity. It was Sert’s, and Spain’s, homage to world peace. And yet, by the time it was actually installed in the League’s Palais des Nations (“Palace of Nations”) building in Geneva, Switzerland, it had become a symbol of war —and, eventually, of the League’s own demise.