By Ezra Rosser

Having become the officially backed U.S. city to bid on the 2024 Olympic Games, Boston now faces the problem that the national gains of hosting the Olympics are under-recognized and the local losses associated with creating Olympic venues are under-compensated. The failure to recognize and account for the winners and losers when it comes to hosting the games is somewhat ironic given that the Olympic Games are all about recognizing minute differences, down to hundredths of a second, between athletic performances. Professor Ilya Somin recently published a powerful op-ed opposing the use of eminent domain to build Olympic stadiums in Boston. The op-ed makes a compelling case that, at the local level, the benefits do not outweigh the significant costs of using eminent domain for this purpose. Somin explains, stadium subsidies exceed the the benefits that derive from such stadiums, economic growth that proponents assert will result often fails to materialize, and generally speaking hosting the games “tends to be a massive boondoggle for cities.” Yet, one can agree with Somin and still think that not only should the games go forward, but also that eminent domain is an appropriate tool. Put differently, the problem is not necessarily the use of eminent domain but the failure to fully account for the gains and losses of the Olympics. A purely local accounting of costs and benefits does a good—though not a perfect—job highlighting the dangers that come with hosting the games but fails to give adequate credit to the benefits and to the possibility that society can do a better job sharing the costs of these important events.

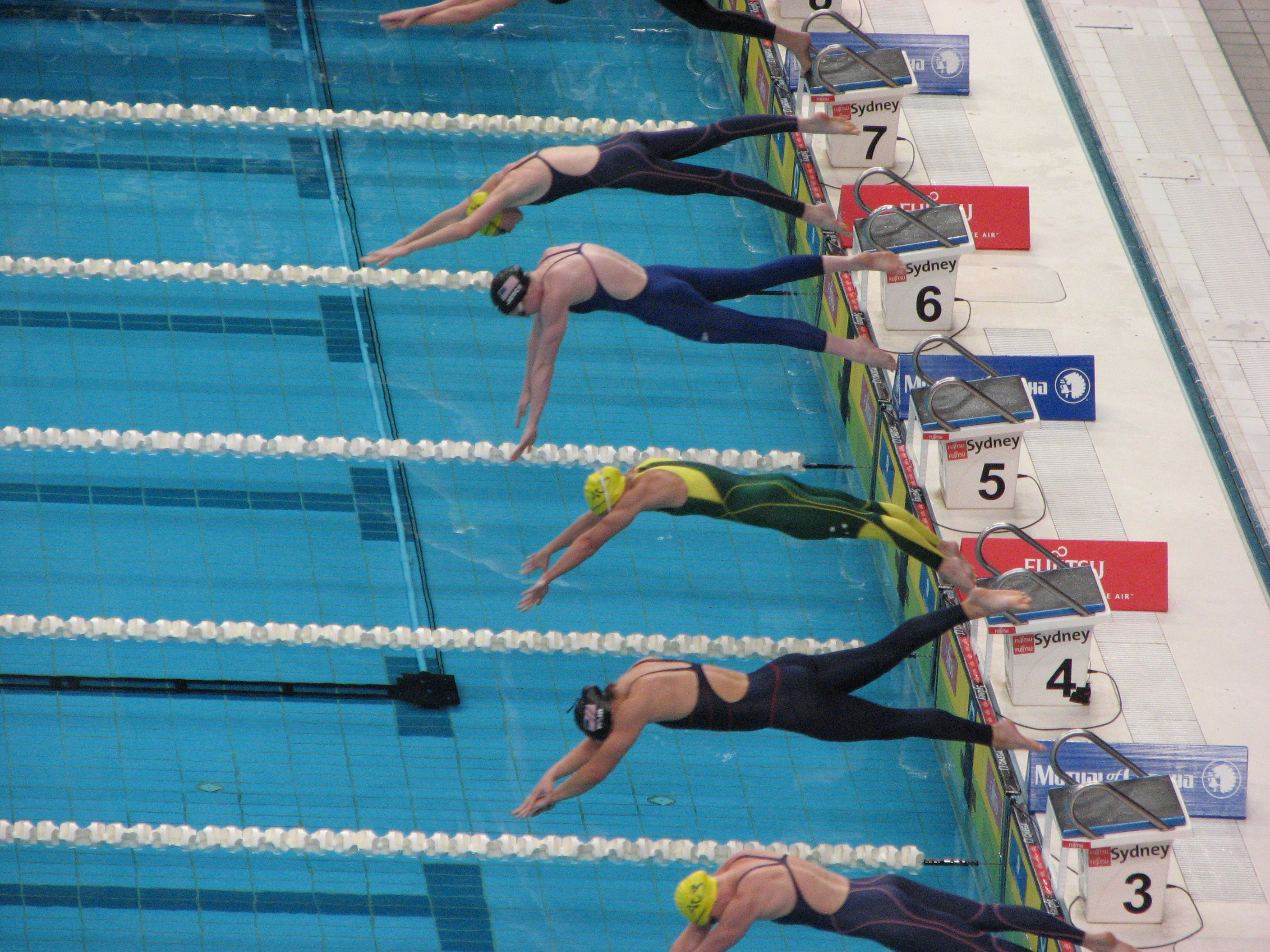

Missing from Somin’s account of the costs of hosting the games are the non-monetized, or at least only partially monetized, benefits of the Olympics. There is real value in promoting sport and recognizing athletic greatness on a global scale. When Usain Bolt crushed the 100 meter sprint, when Gabby Douglas triumphed in gymnastics, and when Michael Phelps showed his swimming dominance, for example, the human spirit was lifted and we learned more about the human condition through the games. Although hard to quantify, there is a real gain in kids dreaming about and working towards their next sporting event or even the Olympics. And though we might want quantify these gains, the value of the Olympics extends further than that. Bolt, Douglas, and Phelps are better role models than the Kardashians, and our society is better for celebrating the work ethic, dedication, and, yes, achievements of Olympic athletes.

The games should go on, but with greater recognition of the national value of the games and of the need to compensate for local losses. Although there are examples of burden sharing across localities and even countries (for example, Korea and Japan co-hosted the 2002 World Cup), typically a single area is asked to bear much of the cost of the games even though the games benefit the entire nation and indeed the world. Some of these costs are readily apparent (the expense of building new stadiums, the increased traffic associated with major sporting events, etc.) and some of the costs are only discovered long after the event itself (the problem of how to find a use for old stadiums given land’s memory, the loss of community following “voluntary” or forced sales to clear space for Olympic facilities, etc.). Distributing these losses fairly could involve a combination of national, tax-funded support for cities selected to host the games and providing supplemental, bonus awards of above-market compensation to property owners should the use of eminent domain be necessary.

As with any large development project, there is a very real concern—and it is a concern that echoes those that animate much of my work—that projects will disproportionately be located in poor areas. Therefore, it is crucial that advocates work to assure that the interests of residents in those areas are fully presented and protected. By bringing to light the full costs of proposed projects and ensuring residents receive supplemental payments when the state forces sales, advocates can play an important role protecting the interests of the poor and spreading the costs of the games beyond politically vulnerable communities.

The decision of whether or not to host the Olympics, and the related decision on whether or not a host city should ever use eminent domain, should not be made on the basis of local cost-benefit analysis alone. Once Americans recognize that the benefits of the games flow to the whole nation, to other nations, and even to humanity itself, it is easier to insist that cities not be disproportionately responsible for bearing the bulk of the short- and long-term costs of hosting the Olympics. Moreover, as a wealthy and powerful country, the United States arguably has a responsibility and role to play in putting on the games. If a great American city such as Boston—which already boasts much of the infrastructure needed to support the games—is not able to host the Olympics, perhaps the games should just be cancelled. Clearly, my view is that they should not be. Let me end by noting that though my son is only five years old now, we hope you will join us in 2030 to cheer him on as he leads El Salvador’s first Olympic Curling Team to victory. Okay, so that is only a dream, but dreams are what the Olympics are both built upon and inspire.