By Tommy Tobin*

It’s an unfortunate reality that food can sometimes make people sick. In just one year, nearly 20,000 Americans were hospitalized due to Salmonella bacteria alone, and over 375 individuals died.

In concert with other agencies, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plays a leading role in preventing foodborne illness. For scientists, pinpointing the exact cause of a foodborne illness is difficult. They race against time to find the source, down to the farm, plant, or processing method. For every moment answers evade investigators, more Americans are potentially exposed to pathogens lurking in everyday products, from peanuts to pico de gallo.

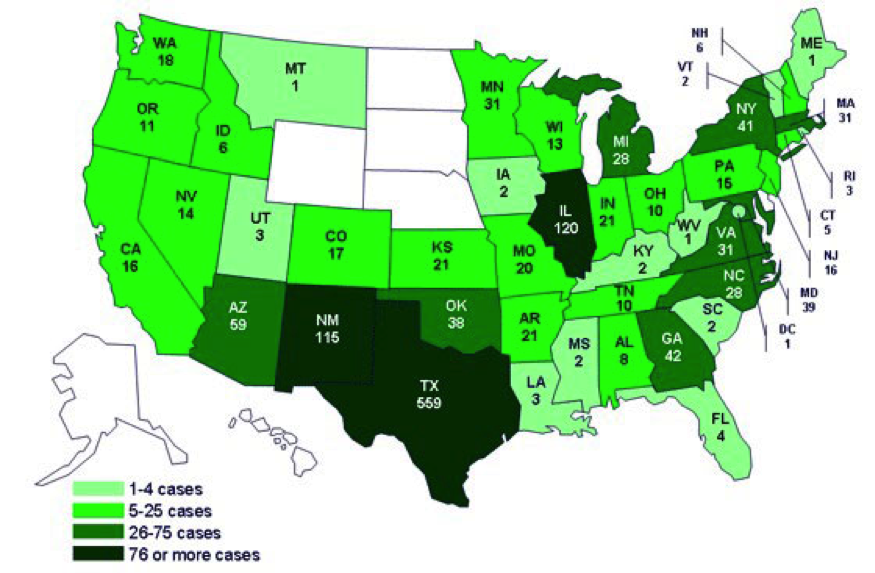

In 2008, the nation faced one of the largest Salmonella outbreaks ever identified. Reports started in May from New Mexico, then Texas. All told, approximately 1,500 Americans across 43 states and the District of Columbia fell ill. According to the New England Journal of Medicine, it is likely that far more cases occurred than were actually identified.

Figure 1: CDC Outbreak Summary of Salmonella Saintpaul outbreak in 2008.

Initially, food safety investigators identified tomatoes as the cause of the Salmonella outbreak. Statistical analysis of early cases showed a strong correlation between eating raw tomatoes getting sick. By June 7, 2008, public advisories went out nationwide to warn the American public against eating certain types of tomatoes.

Unfortunately, the race to protect the food supply may lead to initial conclusions being proved wrong. Such was the case here. After multiple investigations, tomatoes were cleared. Instead, jalapeño and serrano peppers were identified as the culprits. According to researchers, one reason for the delay may have been that the peppers were usually used in small quantities across dishes and may not be remembered or recognized by those who had consumed them.

The implication of hot peppers as the cause of the outbreak was cold comfort for tomato producers. Consumers’ taste for tomatoes suddenly disappeared after tomatoes they had been implicated—even if mistakenly so—in a nationwide food safety outbreak. More than just sour grapes, farmers found that much of the value of their crops had been wiped out.

A group of tomato producers filed suit against the federal government alleging that the public health warning amounted to a regulatory taking of their perishable tomato crops. In Dimare Fresh, Inc. v. United States, the Federal Circuit was “not unsympathetic to the Tomato Producers’ predicament” but denied the extension of its takings jurisprudence to such public health warnings, even if such warnings were incorrect or premature. The Dimare Fresh Court recognized a long-standing maxim that government officials are provided the “greatest leeway” to act to protect public health and safety. It noted that the FDA simply provided information, and the agency did not prohibit any tomatoes from sale. Therefore, the court concluded that the FDA did not infringe on any of the tomato producer’s property rights.

A South Carolina tomato farmer tried a different strategy. Instead of suing under a property rights theory, Seaside Farms sued under the Federal Torts Claims Act. This tomato farm had harvested its tomato crop when the warning was in effect. The firm alleged that FDA had negligently issued the contamination warning, impairing the value of Seaside’s crop by over $15 million.

On December 2, 2016, the Fourth Circuit rebuked Seaside Farms’ tort theory. The Seaside Farms court refused “to place FDA between a rock and a hard place,” as it would face tort liability from firms that were affected by incorrect warning as well as massive tort liability from consumers whose illnesses could have been prevented if a warning was issued sooner.

Writing for the unanimous panel, Judge Wilkinson noted that FDA properly exercised its discretion when it issued its contamination warnings and was protected by governmental immunity. Judge Wilkinson went on to note that:

Every public health emergency is different. There is no boilerplate warning that can account for the unknown variables of a pathogenic outbreak. There is little room for leisured hindsight when the decision is one that must be made under the pressure of events and, in many cases, on the basis of imperfect information.

The Government Accountability Office has identified food safety, and its federal oversight, as a “High Risk Issue” currently facing the country. These recent federal court rulings may provide food safety officials with greater ability to act quickly as they fight to secure our nation’s food supply. Hopefully, these battles are fought in the field and in the lab rather than in the courtroom.

*Tommy Tobin recently served as Instructor of Law at UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, where he taught a module on food law and policy. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School and the Kennedy School of Government.