By Mondaire Jones, Marcela Mulholland, and Julian Brave NoiseCat*

Climate change is coming for all of us. But its destruction will disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color, and coronavirus has offered us a preview of how that might look.

People who live in low-income communities and communities of color have been far more likely to contract coronavirus. Residents of Peekskill, New York, which at $54,839 has the second-lowest median household income of any municipality in Westchester County and a majority black and Hispanic population, are four times more likely to contract coronavirus than those in New Castle, New York. At $211,105, New Castle has the second-highest median household income of any municipality in Westchester and a mere five percent of its population is black or Hispanic.

One reason for that disparity is environmental injustice. Low-income communities and communities of color have long borne the brunt of environmental injustice. They are significantly more likely to breathe hazardous air, live in homes that endanger their health, and lack access to adequate public transit.

Congress must reimagine what environmental justice looks like in low-income communities and communities of color across this country, including in cities like Peekskill.

Peekskill’s poor air quality endangers its residents. The city houses several major sources of air pollution, including a Wheelabrator plant that incinerates Westchester County’s garbage and several major thoroughfares that bring carbon-spewing cars and trucks directly through Peekskill’s population centers. This air pollution has been deadly for Peekskill residents, who suffer from asthma at alarmingly high rates—their rate of asthma-related emergency department visits is more than four times as high as nearby Somers—and the highest infant mortality rate in Westchester County. The recently built Algonquin Incremental Market (“AIM”) Pipeline, which ferries natural gas right next to Peekskill, threatens to make matters significantly worse. Were it to rupture, it could cause serious illness and force residents to evacuate.

Peekskill’s housing stock also presents significant health hazards to community members. The city is home to some of the oldest housing in the county: just 51 of its 10,000 housing units have been built since 2010. Seventy-seven percent of housing units were built when lead-based paint was widely used; as a result, the town has the highest rate of lead poisoning in Westchester County. Meanwhile, Peekskill is in the throes of a housing crisis that leaves hundreds of people either homeless or living in overcrowded homes. Over a third of renters in Peekskill spend more than 50 percent of their income on rent. In fact, someone in Peekskill earning the average renter wage of $14.60 per hour must work over 80 hours every week to afford fair market rent. Meanwhile, the average waiting list time for Section 8 vouchers is 42 months—nearly four years.

Some of Peekskill’s automobile traffic, and the concomitant air pollution, should in theory be mitigated by Westchester’s relatively dense public transit coverage. But Westchester’s public transit is woefully inadequate to meet the needs of its commuters. The Metro North offers a great way to get into New York City, but limited options if you live and work in Westchester County, like 78 percent of Peekskill commuters. Decades of neglecting Peekskill’s public transit have made it impossible to get nearly anywhere without a car—a 25-mile trip from Peekskill to Westchester’s job center of White Plains takes 30 minutes by car, but at least 1 hour on the Bee Line Bus at peak times. It should be no surprise, then, that people opt to drive. That might be why 57 percent of Peekskill commuters drive alone to work, and just 18 percent take public transit.

Meanwhile, Peekskill’s municipal spending has done little to combat these systemic inequities. Just 14 percent of the city’s 2019 general fund budget was devoted to housing and home services, health care, and transportation, while 22 percent of the budget was spent on police.

In order to tackle climate change and environmental justice, we need national solutions. Congress must pursue policies that directly address the needs of communities living on the front lines of environmental harm. That includes directly investing in air quality, housing, and public transit in cities such as Peekskill—and thousands of other communities throughout our country—that have suffered from generations of disinvestment.

Here’s what that should look like.

We must guarantee communities like Peekskill their right to clean air. Investments in public transit will reduce the number of cars spewing pollution through the thoroughfares of downtown Peekskill. Funding for zero-waste initiatives would reduce the amount of trash sent to incinerators like the Wheelabrator plant, and tougher clean air standards would force operators to limit the harmful emissions that come from industrial facilities. Rapidly transitioning our grid to renewable energy would render fossil fuels obsolete, removing the significant public health hazards that the AIM Pipeline presents.

Taking action to ameliorate Peekskill’s severe housing shortage could also dramatically lower its carbon emissions. The solution to Peekskill’s housing crisis is simple: build new, high-quality, affordable units and upgrade the existing substandard units to make them sustainable, comfortable, and safe. Doing so would also help address climate change, as residential and commercial buildings are responsible for nearly 40 percent of all U.S. energy consumption.

Congress should pass the Green New Deal for Public Housing Act (H.R. 5185), which would rehabilitate our country’s more than one million public housing units while making them carbon-neutral. That would create over 240,000 jobs nationwide each year, many in high-paying construction sectors, and reduce public water and energy bills by 30 and 70 percent, respectively. While we are at it, we can retrofit non-public housing to reduce its carbon footprint, remove hazards like lead paint, and weatherize homes to withstand unavoidable aspects of climate change. We must also build millions of new units of mixed-income housing near public transit that meet the highest environmental standards. Doing so would provide people of all income levels an opportunity to live in health-affirming, carbon-neutral units—and by increasing housing supply, it would bring outrageous housing costs down for everyone.

To truly unlock economic opportunity for Peekskill’s residents, while reducing our collective carbon footprint, we must offer residents a more sustainable way to get to work than driving. Building high-quality transit infrastructure like commuter and light rail would promote access to schools, health services, and grocery stores—all pathways to economic mobility. Additionally, the transition to modernized public transit would create hundreds of thousands of good-paying jobs nationally through construction projects and economic growth, and because jobs that were previously geographically out of reach would no longer be inaccessible. At the same time, upgraded public transit would significantly reduce air pollution and carbon emissions: a fully occupied train car is 15 times as fuel efficient as someone driving alone in an automobile and can be powered more easily through renewable energy.

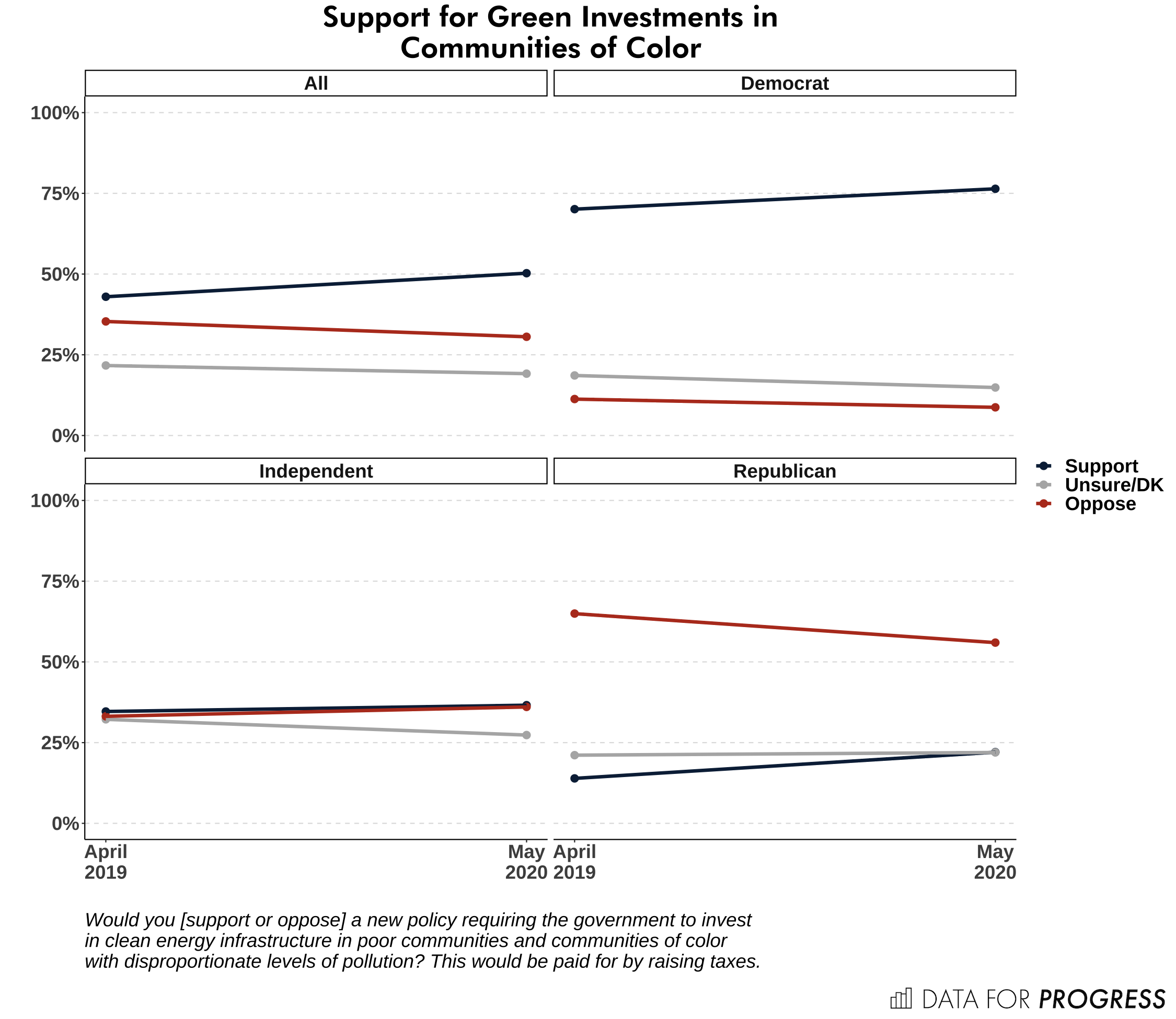

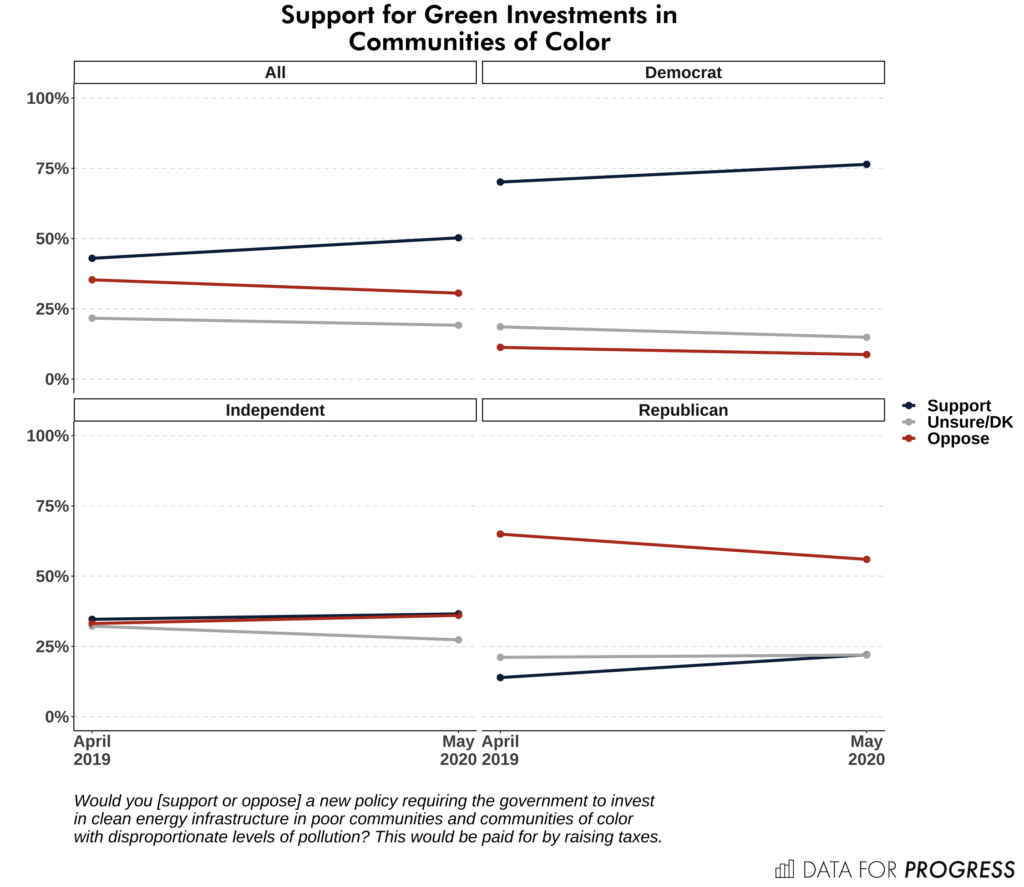

Policies like this already have broad support among the American public. Voters decisively support green investments that would improve air quality, transportation, and housing in low-income communities and communities of color—while reducing electric bills. In a recent poll conducted by Data for Progress and YouGov Blue, an outright majority (50.3 percent) of voters support green investments in poor communities and communities of color, with just 31 percent opposed. That includes support from 76 percent of Democrats, 37 percent of independents (with just 36 percent opposed), and 22 percent of Republicans (compared to 56 percent who oppose, down from 65 percent opposition in the previous poll).

Through green investments, we can dramatically improve the quality of life for people in low-income communities and communities of color like Peekskill. The impact would be felt far beyond Peekskill—it would be felt in towns across New York’s 17th Congressional District, like Haverstraw, Ossining, and Spring Valley, and across the country, like in Flint and Newark. Targeted green investments in low-income communities and communities of color is the right thing to do for the people who need it most, the popular thing to do with the American people, and the smart thing to do for the future of our planet.

* Mondaire Jones is a resident of South Nyack, N.Y. A graduate of East Ramapo public schools, Stanford University, and Harvard Law School, Mondaire is a former Justice Department staffer under President Obama and lawyer in the Westchester County Law Department. He is a Democratic candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives in New York’s 17th District, which includes all of Rockland County and parts of central and northern Westchester County.

Marcela Mulholland is Deputy Director for Climate at Data for Progress.

Julian Brave NoiseCat is Director of Green New Deal Strategy at Data for Progress, a think-tank, and narrative change director for the Natural History Museum, an artist and activist collective. He is also a correspondent for Real America with Jorge Ramos and contributing editor for Canadian Geographic.