By Christopher Mirasola

October was not a good month for China in the South China Sea. The United States Navy sent a guided missile destroyer on a freedom of navigation exercise to assert that artificial islands are not entitled to a 12 nautical mile territorial sea. Despite strong protests from Beijing, the exercise was unsurprising. Washington had been hinting for weeks at a stronger response to China’s maritime claims. Far more surprising was a decision only three days later from the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in which the Court unanimously decided to hear all fifteen claims against China’s policy in the South China Sea.

Background

In January 2013 the Philippines invoked Article 287 of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to challenge China’s claims to a majority of the South China Sea.

As stipulated by Article 287, an ad-hoc tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration was convened and invited both parties to submit briefs based on the Philippines’ statement of claim. China, however, refused to recognize the PCA’s authority and opted out of the Court’s formal proceedings. After hearings that closed this past July, the PCA had to decide whether UNCLOS gave it the authority to adjudicate the Philippines’ claims against China.

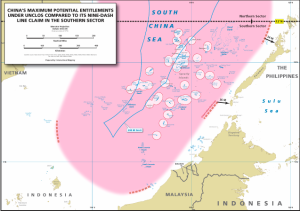

Broadly speaking, the Philippines has three claims. First, it argues that the nine-dash-line is contrary to UNCLOS provisions, which should be the only basis for maritime sovereignty and jurisdiction. Second, it asserts that a number of contested maritime formations (i.e., reefs) are not entitled to a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone or the adjoining continental shelf. Third, it contends that China’s law enforcement and fisheries behavior in the South China Sea is contrary to UNCLOS obligations and interferes with Philippine sovereignty. Of course even if the Philippines won on all these claims, the PCA cannot settle which country is sovereign over islands in the South China Sea. But even if we assume that China has uncontested sovereignty to all properly defined islands, a decision favorable to the Philippines would leave China with far less jurisdiction than it currently claims under the nine-dash line.

The Court’s Decision

We can decompose the PCA’s analysis into three parts.

The arbitration was convened correctly

The Philippines was justified in calling an ad-hoc tribunal since neither country opted for a specific type of dispute resolution when they adopted UNCLOS. The Court also found that China’s non-participation did not impact the PCA’s jurisdiction because Annex VII Art. 9 states that, “Absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings.” They also cited ways in which the PCA protected China’s rights, including repeated invitations to comment on procedural steps, advance notice for hearings, transcripts, and an invitation to join formally at any stage. The Court similarly argued that Vietnam’s non-participation didn’t impact the PCA’s jurisdiction despite the fact that it has rival claims to the same region.

The Court’s most stinging rebuke of China’s non-participation, however, was to adopt a weaker standard for whether the Philippines abused process in requesting this arbitration. The PCA defined ‘abuse of process’ as “blatant cases of abuse or harassment” because China did not request a more rigorous test under Article 294. By adopting such a weak standard it was much more likely that the Philippines would win on this particular jurisdictional argument. While we cannot be sure that a more stringent standard would have changed the Court’s decision, China certainly lost an opportunity to more substantially protect its interests.

Past agreements between China and the Philippines do not affect whether the PCA can adjudicate this dispute

The PCA focuses on three agreements signed by both countries: (1) the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (an agreement between all ASEAN countries and China to lessen regional tensions by working towards a joint code of conduct), (2) Joint China/Philippines statements to find a peaceable solution, and (3) the 1976 Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (an agreement to settle differences by peaceful and cooperative means). China argued that these documents precluded the Philippines from starting arbitration under Art. 281 and 282. The PCA, however, found that each of these documents (1) didn’t represent a settlement between both parties, (2) didn’t exclude other dispute resolution mechanisms, and (3) don’t require that the parties indefinitely pursue unsuccessful negotiations.

The PCA does not necessarily have definite jurisdiction over all fifteen Philippine claims

And this is where the story gets interesting. The PCA found that it has definite jurisdiction on seven claims, reserved judgment on another seven claims, and asked for clarification on a final claim. In short, it found that seven of the claims presented issues where the jurisdictional and substantive questions were too closely connected to make a preliminary decision.

Implications

The PCA dealt China a substantial blow in its bid to solidify control within the nine-dash-line, but it is far too early for the Philippines to pop the bubbly. The Court will now hold additional hearings, decide if it has jurisdiction for the seven reserved claims and render a decision. This puts China in a bind if it continues to boycott the proceedings since it will again run the risk of loosing input on pivotal legal questions. More problematic is that China has never articulated a robust legal defense for its historic claims in the South China Sea. There will be less material the judges can use to independently construct a likely Chinese response to Philippine arguments. Without a robust defense, it seems more likely that China’s historic claims may fail to convince the Tribunal.

We must, however, recognize the limits of even this most pro-Philippines scenario. The Court will not resolve territorial disputes to contested islands like Itu Aba (currently garrisoned by Taiwanese forces). It will not resolve boundary conflicts between overlapping Exclusive Economic Zones and territorial seas. Given China’s official pronouncements, it also will not change the ongoing increase in Chinese construction and presence in the short-term.

But we can begin to ask how this decision may start to change the playing field for Southeast Asian countries that dispute China’s claims. Whether it might catalyze more coordination between countries that have been deeply divided about how to balance regional strategic concerns with the reality of economic dependence on Beijing. Though only halfway through this arbitration, we may already be witnessing the start of a much different chapter in the South China Sea.

Christopher Mirasola is a 2018 J.D./M.P.P. candidate at Harvard Law School and Harvard Kennedy School. He is an Executive Symposium Editor of the Harvard International Law Journal.