Apr 18, 2025 | Online Scholarship, Perspectives

*Zej Moczydłowski

1. Introduction

Regardless of one’s perspective, the case of Dominic Ongwen is one of the saddest in the history of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Even to those seeing him as a perpetrator of terrible war crimes, specifically of a sexual nature, it is undeniable that his abduction at a young age and subjection to the indoctrination of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) is cause for sorrow. Meanwhile, those who focus on his dual status as not only a perpetrator—but also a victim himself—cannot deny the heinous, horrific, and sometimes unspeakable sexual and gender-based violence for which he was responsible.

Neither of these disparate views of Ongwen is wrong. Yet, those contemplating them have largely failed to consider their overlap and how the intersection should inform and influence the opposing view. This paper seeks to flesh out this issue, examine Ongwen from both sides and argue that the need to punish sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV)[1] caused the trial to largely ignore Ongwen’s status as a victim-perpetrator. It concludes by proposing how, in similar prosecutions, these views can be considered contemporaneously by creating a bifurcation of charges. In such cases, comparable defendants could face one prosecution for charges relating to SGBV—where defenses pertaining to their history as child soldiers would not be considered—and another prosecution for charges relating to all other aspects of warfare where defenses relating to their being a victim-perpetrator would be considered heavily.

Part 2 provides a general introduction to the LRA and Ongwen. Part 3 examines the case at large, focusing on two issues: the SGBV for which Ongwen is arguably best known and Article 31(a) problems arising from his having been a child soldier. Part 4.1 looks at the history of how SGBV has been previously addressed in international courts, while Part 4.2 considers the history of child soldiering and how claims of mental defects have previously been approached relative to their culpability in a person’s actions. The case is and, in part, ensuing academic discussions are critiqued in Part 5, primarily touching upon the significance of the novel prosecution of forced pregnancy and the dismissal of Ongwen’s Article 31(a) defense. Lastly, Part 6 proposes that in future such cases, the actions of victim-perpetrators such as Ongwen should be considered through an approach that considers SGBV separately from traditional conflict-related crimes.

2. General History

2.1 The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA)

Formed in Uganda in 1986 as a political rebellion, over the subsequent decades, the LRA grew into a particularly vicious organization known for its use of enslaved child soldiers, as well as “its massacres, sexual-based violence, mutilations, pillage, and abductions.”[2] Led by Joseph Kony, the group operated in Uganda and was directly in conflict with the Ugandan People’s Defense Forces (UPDF), utilizing weapons varying from machetes and knives to machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades.[3]

In its earlier years, the LRA received support from Sudan through weapons, training, and base locations.[4] While fighting its own conflict in Uganda, it also fought on behalf of Sudan against the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA).[5] However, after the terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, the Sudanese government was persuaded to let Ugandan troops enter Sudan and rout the LRA from bases there, leading to several LRA units crossing back into Uganda and the events addressed in Ongwen.[6]

By 2006, the LRA was responsible for the displacement of over one million Ugandans, over 100,000 murders, and the abduction of tens of thousands of children. Many of these children were put on the front lines and forced to “kill, mutilate, and rape family members, schoolmates, neighbors and teachers.”[7]

2.2 Dominic Ongwen

While Dominic Ongwen’s exact age is unknown, it is believed that he was born in Northern Uganda around 1978 in Coorom and was abducted by the LRA around 1988, when he was somewhere around the age of ten or eleven.[8] During his abduction, “he was forced to watch the killing of a young relative by child soldiers; forced to participate in a reprisal attack on a village [ and] [] forced to skin alive a young abductee who had tried to escape.”[9]

The LRA abducted children because they were easier to indoctrinate and coerce through a system of physical and psychological abuse in which they “were forced to beat and/or kill other abductees… witness severe violence being inflicted on others… and constantly [face] physical violence or death if they broke LRA rules.”[10]

After his abduction, Ongwen rose through the LRA ranks. By 2002—the timeframe relevant to the charges—he had risen to the rank of Major and was a battalion commander.[11] By the end of 2004, he was promoted to Colonel and then Brigadier General.[12] In this command capacity, and sometimes as a direct perpetrator, he engaged in the conduct for which he was charged.

3. The Case

In December 2003, Uganda referred crimes allegedly committed by the LRA to the ICC, and in July 2004, the Prosecutor announced that an investigation was underway. On July 8, 2005, Pre-Trial Chamber II issued arrest warrants under Article 58 against Joseph Kony and members of the LRA leadership; Ongwen was one of five individuals named.[13]

A decade later, in January 2015, Ongwen voluntarily surrendered to U.S. Special Operations Forces and the UPDF, was transferred to authorities in the Central African Republic (CAR), and then—after confirming to CAR authorities that he intended to surrender to the Court willingly—custody was transferred to the ICC.[14] Ongwen appeared before Pre-Trial Chamber II on January 25, 2015; his case was severed from Kony et al. on February 6, 2015.[15] Despite the severance of Ongwen’s case from that of Kony and other LRA leaders, the Defense would go on record that they believed Ongwen became a stand-in for Kony in a case that examined all of the LRA’s atrocities. Ongwen attempted to distance himself from the LRA’s leader, but, in the eyes of his attorneys, the Chamber ignored him and ultimately “…treated [Ongwen] as a scapegoat.”[16]

The Chamber issued a decision confirming charges against Ongwen on March 23, 2016,[17] charging him with war crimes and crimes against humanity against Ugandan civilians between July 1, 2002, and December 31, 2005.[18] “The numbers in the Ongwen case [were] staggering. Mr Ongwen was charged with 70 counts and 7 modes of liability—the most of any single defendant at the ICC.”[19] The Chamber broke charges into three categories: crimes committed during four attacks against internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, SGBV perpetrated by Ongwen himself against women in his household, and “other sexual and gender-based violence and conscription and use in hostilities of children under the age of fifteen.”[20]

Relating to the attacks against IDP camps, Ongwen was charged in Counts 1–49 under various modes of liability for crimes against humanity and war crimes such as attacking civilians, murder, torture, cruel treatment, other inhumane acts, and political persecution.[21] These crimes, however, are not the focus of this essay and will not be expanded upon.

SGBV charges, as previously noted, were split into two categories. Counts 50–60 were related to acts committed by Ongwen himself (forced marriage, torture, rape, sexual slavery, enslavement, forced pregnancy, and outrages against personal dignity).[22] Counts 61–68 were related to SGBV committed by others under his command (forced marriage, torture, rape, sexual slavery, and enslavement).[23] [24] This case was the first time in ICC history that forced marriage and forced pregnancy were charged as separate crimes.[25]

However, another novel issue brought up in Ongwen was the fact that he is believed to be the only former child soldier to face ICC charges.[26] This led to his Defense arguing: “[f]rom being a child, up to when he reached the time of 2002 up to now, given the history, a given his life-long experiences, he was forced into his situation against his will. He is a victim.”[27] Ongwen’s childhood abduction resulted in this being the first ICC case to argue for excluding criminal responsibility under Article 31(1)(a) and (d).[28]

Article 31(d) deals with duress, whose discussion is distinct from the theory of mental defect resulting from trauma endured as a child soldier. However, it should be noted that the Defense attempted to introduce a novel approach to mental duress, which overlapped with the mental defect defense. They argued that, rather than being faced with the traditional “gun-to-the-head” presentation of duress, Ongwen faced duress due to Kony’s abuse of spiritualism to control those under his command and “to cement his power over vulnerable child abductees.”[29] In fact, the Charging Documents against Kony flatly stated that “members of the LRA believed he had spiritual powers and was omniscient, beliefs which Kony perpetuated to exert control over the LRA.”[30] However, the Chamber rejected these arguments, arguing that at the point of the alleged crimes, Ongwen was so senior a member of the LRA that it would be difficult to suggest that he kept committing war crimes out of fear for Joseph Kony.[31]

Moving to Article 31(a), a person would not be criminally responsible if, at the time of their conduct, they suffered “from a mental disease or defect that destroys that person’s capacity to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his or her conduct, or capacity to control his or her conduct to conform to the requirements of law.”[32]

Regarding this defense, Ongwen’s team introduced expert testimony. It concluded that Ongwen suffered from mental defect and disease due to “his forced abduction by the LRA around 1987, continued through his years in the LRA…”[33] They claimed these diseases destroyed “Ongwen’s capacity to appreciate the unlawfulness or nature of his conduct and capacity to control his conduct to conform to the requirements of law.”[34] The Defense argued that Ongwen’s mental development ceased at the “time he was abducted, and this ensured that throughout the LRA, and even today, he has a ‘child-like’ mind which is incapable of forming the required mens rea for crimes or determining right from wrong.”[35] Their argument was not that Ongwen should have been tried as a juvenile but that his stunted mental development prevented him from developing the requisite capacity to commit these crimes with intent.

The Chamber, however, was not convinced that an Article 31(a) defense existed. It “identified six issues relating to the methodology used by [the Defense experts] in carrying out their assessments.”[36] It stated that a “number of issues, in particular as concerns the methodology employed, [affected] the reliability of the evidence provided by [the Defense experts], to the extent that the Chamber [could not] rely on it.”[37]

Specific issues relating to the Defense experts included their having blurred the line between their roles as forensic experts and treating physicians,[38] having failed “to apply scientifically validated methods and tools for use as a basis for a forensic report,”[39] having used “diagnostic labels from an outdated international classification system,”[40] and “[failing] to take into account other sources of information… readily available to them.”[41]

On February 4, 2021, the Trial Chamber found Ongwen guilty of 62 of the 70 Counts with which he was charged.[42] The eight counts of which he was not guilty were all related to the attacks on IDP camps; he was found guilty of every SGBV crime with which he was charged.[43]

During sentencing, the Chamber said that under normal circumstances, the gravity of the crimes committed by Ongwen would have resulted in life imprisonment.[44] However, it also noted that it was confronted “with a unique situation of a perpetrator who willfully and lucidly brought tremendous suffering upon his victims, but who himself had previously endured grave suffering at the hands of the group of which he later became a prominent member and leader.”[45] Consequently, Ongwen was not sentenced to life imprisonment but twenty-five years.[46]

Judge Raul C. Pangalangan filed a Partially Dissenting Opinion in the sentencing, believing a thirty-year sentence—the maximum permissible under Article 78(3)—was more appropriate.[47] He argued that not imposing a life sentence already took into account Ongwen’s personal situation.[48]

The Defense appealed both the conviction and sentencing. While appealing the conviction, in grounds for appeal 27, 29, 31–32, and 37–41, they “alleged errors in the Trial Chamber’s rejection of the Defence Experts’ evidence.”[49] The Appeals Chamber decided that the Trial Chamber was correct in finding that it could not rely on the Defence Experts’ evidence.[50] It also rejected all other grounds for appeal of the conviction and confirmed both the conviction[51] and sentencing decisions.[52]

In February 2024, the Trial Court issued a Reparations Order, stating the “amount required to provide the reparations awarded in this case to the direct and indirect victims of the crimes… would be approximately €52,429,000 EUR.”[53]

4. Historical Context

4.1 SGBV

The history of warfare is sadly rife with sexual and gender-based violence. Evidence, both historical and anthropological, “suggests that rape in the context of war is an ancient human practice, and that this practice has stubbornly prevailed across a stunningly diverse concatenation of societies and historical epochs.”[54]

In modern contexts, SGBV is no less common. Examples include the rape and murder of Chinese women during the 1937 invasion of Nanjing, mass rapes of German women at the end of WWII, and mass rapes of women in “modern-day armed conflicts such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, Uganda, the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, Peru, the Democratic Republic of Congo, [Darfur], Libya, Iraq, and Syria.”[55] In short, “all forms of sexual violence, including forced pregnancies, have been used as tools of oppression and control over women and girls from time immemorial. Historically, however, the rules and practices of international criminal law have often overlooked violations of reproductive rights.”[56] This truth is visible when one examines the evolution of international criminal courts, which only recently started addressing SGBV as a form of crime distinct from other war crimes and crimes against humanity.

For example, the earliest manifestation of a modern international court, the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg (IMT), did not expressly prosecute SGBV despite having the ability to “punish the overwhelming number of sexual assault crimes that took place during World War II.”[57] The IMT just included SGBV “as evidence of the atrocities prosecuted during the trial.”[58] Meanwhile, in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), “rape crimes were expressly prosecuted… albeit to a limited extent and in conjunction with other crimes.”[59] It is worth noting that “the inclusion of rape in the Tokyo indictments resulted in the first prosecution of the rampant sexual violence of World War II.”[60]

The approaches to SGBV in the IMT and IMTFE have historically been seen as too tangential. Critics point out that while steps may have been taken in the right direction, they were relatively unproductive because those tribunals largely ignored SGBV.[61] For example, at the IMT, “French and Soviet prosecutors introduced, ‘evidence of vile and tortuous rape, forced prostitution, forced sterilization, forced abortion, pornography, sexual mutilation, and sexual sadism.’ Despite this evidence, no defendants were explicitly prosecuted or convicted for sexual crimes before the Nuremberg Tribunal.”[62]

Decades later, subsequent criminal tribunal iterations began to tackle SGBV in the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Dianne Luping, a Trial Lawyer in the Prosecution Division of the Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC, points out that the ICTY statute referred explicitly to rape; in contrast, the ICTR statute referred expressly to rape and enforced prostitution.[63] She adds that the way both statutes classified rape as a crime against humanity was “ground-breaking.”[64] Another author argued that in the ICTY and ICTR, “crimes committed exclusively or disproportionately against women and girls… secured reluctant but nonetheless ground-breaking redress.”[65]

Rape was first charged as a war crime and crime against humanity in the ICTY during Prosecutor v. Gagovic.[66] There, “the prosecutor focused exclusively on sexual assault and qualified rape as a violation of the ICTY’s grave breaches provision, a violation of the laws and customs of war, as well as a crime against humanity.”[67] All three defendants were found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity of sexual violence.[68] Likewise, at the ICTR, Prosecutor v. Akayesu,[69] ruled for the first time “that rape and other forms of sexual violence were used as instruments of genocide… and crimes against humanity.”[70]

Progress continued with the creation of the ICC. The Rome Statute enumerated multiple sexual crimes and demonstrated “an unprecedented degree of gender sensitivity in international criminal law.”[71] This explicit criminalization was noteworthy because prosecuting crimes requires that they be defined. Previously, it had been possible to prosecute SGBV under more general provisions, but that ability had rarely been exercised.[72] Specifying the nature and elements of crimes made it easier for prosecutors to determine when they were applicable and push their inclusion on a list of charges.

Yet, despite these promising steps, in its first twenty years, the only convictions for sexual crimes in the ICC[73] have arguably been Prosecutor v. Ntaganda[74] and now Prosecutor v. Ongwen.[75] One author argues that “although an international court’s success cannot, and should not, be measured simply by its number of convictions, it is evident that the ICC has not fulfilled the objective of ending impunity for gender crimes under international criminal law.”[76]

In addition to the explicit criminalization in the Rome Statute, progress continues, and other successes have been seen despite a lack of convictions. For example, during Fatou Bensouda’s term, the Office of the Prosecutor published a policy for investigating and prosecuting SGBV and made progress in charging them.[77] That publication was then expanded upon in December 2023 by Bensouda’s successor, Karim Khan, whose Office published a new “Policy on Gender-Based Crimes.”[78]

Additionally, juxtaposing the Office of the Prosecutor’s approach to the Lubanga and Ongwen cases demonstrates a changing attitude towards SGBV. In Lubanga,[79] it was “alleged that female child soldiers in Lubanga’s group were routinely raped and used as domestic servants by their commanders;” it was then “argued that this sexual abuse fell within one of the charges that Lubanga was facing, namely, ‘using children to participate in hostilities.’“[80] However, the Prosecutor did not separately charge SGBV crimes, and a majority of the Trial Chamber “refused to determine whether the rape of child soldiers by their commanders would satisfy that test.” [81] As will be noted in Part 5.1, Ongwen marks a departure from that approach.

4.2 Child Soldiers and Related Mental Defect Claims

Many factors make children ideal targets for development into soldiers. They are “physically and psychologically [more] vulnerable than adults, making them easier” to coerce and manipulate, and they are “less demanding than adults,” requiring less logistical support and pay.[82] Consequently, “children are combatants in nearly three-quarters of the world’s conflicts,” posing an ethical and moral dilemma for the professional militaries they confront.[83]

While their use has become more widely known due to increased international coverage of conflicts where they are utilized, the issue of child soldiers was already being addressed in the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions I and II, which both noted that children how had not attained the age of fifteen would not be recruited nor allowed to partake in hostilities.[84] However, the term “child soldier” crystalized in the 1997 Cape Town Principles, which shifted the minimum age of culpability to eighteen and provided a more precise definition of a child soldier:

A person under 18 years of age who is part of any kind of regular or irregular armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to cooks, porters, messengers and anyone accompanying such groups, other than family members. The definition includes girls recruited for sexual purposes and for forced marriage. It does not, therefore, only refer to a child who is carrying or has carried arms.[85]

This definition and age limit was reaffirmed in the United Nations (UN) Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict, which further stated that States Party to the protocol would “take all feasible measures to ensure that members of their armed forces who have not attained the age of 18 years do not take a direct part in hostilities” and “shall ensure that persons who have not attained the age of 18 years are not compulsorily recruited into their armed forces.”[86]

Since establishing this cutoff, few individuals taken into armed groups before turning eighteen have been prosecuted as adults for actions committed during their tenure as child soldiers. The issue first truly came to light at the international level after the creation of the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Due to the pervasive use of child soldiers in that conflict, the question of criminal culpability amongst juveniles was hotly contested.[87] However, in a report prepared for the UN Security Council, Secretary-General Kofi Annan set the tone for future discussions by noting that “although the children of Sierra Leone may be among those who have committed the worst crimes, they are to be regarded first and foremost as victims.”[88]

Local governments in Africa, while having considered the prosecution of child soldiers, have largely not done so. After the Rwandan genocide, over one thousand children were imprisoned for their actions, but few were ever tried.[89] In 2000, the Democratic Republic of Congo executed a fourteen-year-old child soldier, but when it sentenced four others the following year, NGOs intervened and stopped the executions.[90] In 2002, Uganda charged two former LRA child soldiers, but again, NGOs successfully stopped the proceedings.[91]

These examples focus primarily on regional and localized violence by armed groups in Africa. However, the UN has also noted that “owing to the expanding reach and propaganda of terrorist and violent extremist groups, child recruitment and exploitation is in no way limited to conflict-ridden areas.”[92] The imprisonment of Omar Khadr—a fifteen-year-old Al Qaida member charged as an enemy combatant by the U.S.[93]—demonstrates that conversations regarding the prosecution of child soldiers extend across the world and into other types of conflicts as well. The U.S. admission that it held twelve juveniles at Guantanamo Bay[94] shows that combatants under the age of eighteen have been prosecuted for participation in terrorist organizations.[95]

Despite increased attention and efforts to limit the use of those under the age of eighteen in warfare, child soldiering remains prominent and has posed a challenge for militaries tasked with engaging them.[96] With the development of international courts, child soldiers have also begun to pose an issue to those seeking to provide justice for victims of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The question that has arisen is whether child soldiers should “be prosecuted for their crimes.”[97] Standards have not crystallized. “Ongwen is believed to be the only former child abductee to face charges before the ICC,”[98] but—as will be discussed in Part 5—in Ongwen, they arguably largely ignored the problem.

However, considering Ongwen, academics have more deeply considered the issue and have proposed a variety of approaches that could be taken in future cases where a victim—a former child soldier—turned into a perpetrator. A prominent theory, and one which was introduced by the Defense, is that a child abducted at a young age and forced to endure unspeakable horrors has had their moral compass so wholly shattered that they are incapable of understanding the wrongness of their actions.

This theory resembles the “Rotten Social Background” defense raised in United States v. Alexander.[99] There, in an opinion concurring and dissenting in part, Judge Bazelon argued that a “trial judge erred in instructing the jury to disregard the testimony about defendant’s social and economic background. That testimony might well have persuaded the jury that the defendant’s behavioral controls were so impaired as to require acquittal, even though that impairment might not render him clinically insane.”[100]

Regarding international law, one argument presented by the Defense was that his abduction at a young age triggered the protections reserved for trafficked persons and that, as recommended by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, “children who are victims of trafficking should not be subject to criminal procedures or sanctions for offences which are related to their situation as trafficked.”[101] The Defense proposed that under this rationale, his enslavement and trafficking by the LRA provided a “basis for his non-liability and non-punishment.”[102] The Chambers dismissed this argument.

Further examining international law—and while acknowledging that there is no system of binding precedent in the ICC[103]—the primary case that has touched upon the issue of child soldiers is that of Prosecutor v. Lubanga.[104] The Chambers’ treatment of child soldiers under Lubanga’s command merits consideration. “It was essential to the Lubanga decision that the child soldier was contemplated in continuity—once someone was a child soldier, they would always be considered a child soldier through and through.”[105] In Lubanga, the Chamber considered the link between one’s “past as a child soldier and the present as a former child soldier as linear… the child soldiering experience was constructed as ongoing and assured: it rendered the children as victims damaged for life, with their reality today as derivative of their previous suffering.”[106]

Yet, because Lubanga himself was not a child soldier, the case does not precisely fit the facts of Ongwen and, therefore, does not answer an important question that arose there. Namely, at what point—if ever—does a former child soldier finally take the mantle of responsibility for their actions upon their shoulders? In short, does the “hunted… ipso facto become the hunter upon his eighteenth birthday?”[107]

5. Critique

5.1 Changes in Attitudes Regarding SGBV

In Ongwen, the Trial Chamber appears to have taken the ICTY and ICTR’s “ground-breaking”[108] approach towards SGBV and gone further. It approached SGBV more holistically than in any prior case, demonstrating a compassionate approach to the horrors endured by SGBV victims and, for the first time, charging a Defendant with forced marriage and forced pregnancy. Of course, such progress is not itself an end-state. It is just another step in the right direction.

Regarding the Ongwen court’s progressive handling of victims, this was most vividly seen in the treatment of witness “P-227,” a female allegedly abducted and forced into becoming one of Ongwen’s “wives.” “The defence challenged her testimony, noting that P-227 denied having been raped when she spoke with NGO workers directly after her escape, but then claimed she had been raped when interviewed by ICC investigators.”[109] P-227 would explain the discrepancy as being due to the recent nature of the trauma and the NGO workers being male.

The Pre-Trial Chamber, taking “into account her account of trauma and her stated preference for speaking with female investigators,” ultimately found her testimony reliable.[110] “In reaching that conclusion, the judges demonstrated an awareness of the gendered social context that makes it difficult for some women to disclose their experiences of sexual violence, especially when speaking to men.”[111] The Trial Chamber made a similar sensitive choice and agreed to accept the testimony of SGBV recorded at the pre-trial stage. “In making that decision, the Chamber recognized that calling the witnesses to give their evidence a second time would put them under unnecessary strain.”[112] These attitudes, if replicated in future cases, will help ensure that victims, understandably intimidated by the proposition of speaking about their experiences, will not lose their chance at justice simply because they are traumatized and afraid.

The other part of the Ongwen decision that must be noted in this critique is the decision to hold Ongwen responsible for the crime of forced pregnancy. As Julia Tétrault-Provencher notes, the “Ongwen Trial Judgment represents a landmark holding for the prosecution of crimes concerning reproductive rights. This judgment, read in conjunction with independent human rights experts’ scholarship, can shed light on the legal contours of this crime.”[113]

Article 7(1)(g) of the Rome Statute lists forced pregnancy as a crime against humanity when it is “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”[114] Article 7(2)(f) then defines forced pregnancy as “the unlawful confinement of a woman forcibly made pregnant, with the intent of affecting the ethnic composition of any population or carrying out other grave violations of international law. This definition shall not in any way be interpreted as affecting national laws relating to pregnancy.”[115]

However, despite many circumstances since the creation of the Rome Statute where forced pregnancy occurred, Ongwen was the first time the ICC’s charging decisions accused a defendant of this crime. As a case of first impression, it served as a chance for the Court to elaborate on its interpretation of the relevant sections of the Rome Statute. The decision in the trial resulted in mixed feelings at the international level.

On the one hand, in Counts 58 and 59, the Chamber found Ongwen guilty of forced pregnancy[116] and, as such, for the first time, established this crime as one that a prosecutor could successfully charge. However, as pointed out by Tétrault-Provencher, the Chamber did not find Ongwen guilty simply for not giving these women “the free choice to decide whether to continue their pregnancy.”[117] Instead, it found Ongwen guilty because he had committed other crimes in connection with the forced pregnancy. Tétrault-Provencher argues correctly that “the requirement to prove that the perpetrator had the intent of committing another grave violation encourages victims to bring cases of forced pregnancies as the aggravating consequences of another grave violation…”[118] This, in turn, “fosters the idea that reproductive violence cannot be prosecuted on its own.”[119]

Two strategies could be utilized to enforce better the concept that reproductive violence is in and of itself severe enough for condemnation and prosecution. First, Article 7(2)(f) could simply be amended, and the “the unlawful confinement of a woman forcibly made pregnant” clause struck and replaced with a phrase akin to “the forcible impregnation of a woman.” Alternatively, courts could use a broader definition of the “unlawful confinement” clause found in Article 7(2)(f). To confine means “to limit an activity, person, or problem in some way,”[120] therefore, in the context of forced pregnancy, confinement need not focus on physical confinement but rather any unlawful limitation placed upon a woman’s freedom to choose the outcome of her pregnancy. The adoption of either approach would allow for the prosecution of not only those who forced women to bear children by limiting their ability to escape captivity but also those whose actions deprived women of access to reproductive care through other measures.

This issue aside, from a historical perspective, the Ongwen case arguably serves as the current high point in the international criminal treatment of SGBV. Due to its compassionate treatment of witnesses and willingness to pursue novel crimes previously disregarded by other prosecutions, it should be seen as progress in prosecuting particularly vicious crimes, typically against the most innocent victims. That said, the provisions in the Rome Statute that required forced pregnancy to be tied to other grave crimes remain a limiting factor.

5.2 Significance of Dismissal of Article 31 Claims

While Ongwen is believed to be the only former child soldier to face charges before the ICC, the Trial Chamber largely ignored this issue, with little consideration being paid to the arguments that his background as a child soldier left him incapable of differentiating between right and wrong. The Prosecutor was even more silent; her 285-page Pre-Trial Brief, “which details all the charges and Ongwen’s position of authority… makes no mention whatsoever of Ongwen’s background… it is totally (and ironically) silent with regards to the brutalities and coercion that Ongwen himself had endured.”[121]

Ongwen’s lawyers point out that—in their verbiage—the Chambers carved out an “Ongwen Exception” in which “the toxic, traumatic, and often lethal environment of the LRA affected all other abductees, except for Mr Ongwen.”[122] This argument is not without merit, especially when examining that the Chambers largely refused to consider the long-term consequences of the potential long-term psychological damage inflicted upon Ongwen during his childhood. This refusal is most clear in the Chambers’ conclusion regarding the mental defect defense, where it stated that expert witnesses “did not identify any mental disease or disorder in Dominic Ongwen during the period of the charges…”[123] The Chambers’ decision to only look at whether Ongwen demonstrated signs or symptoms of mental illness during the period of the charges underscores that it was largely dismissing Ongwen’s childhood as a mitigating factor.

The point at which the Chamber appears to have begun considering Ongwen’s background and tragic history was at sentencing. Given the ability to sentence Ongwen to life imprisonment, the Chamber declined to exercise that option, stating:

The Chamber is confronted in the present case with a unique situation of a perpetrator who willfully and lucidly brought tremendous suffering upon his victims, but who himself had previously endured grave suffering at the hands of the group of which he later became a prominent member and leader. The Chamber was greatly impressed by the account given by Dominic Ongwen at the hearing on sentence about the events to which he was subjected upon his abduction when he was only 9 years old…

The circumstances of Dominic Ongwen’s childhood are indeed compelling, and the Chamber cannot disregard them in the determination of whether life imprisonment represents the just sentence in the present case… By no means does Dominic Ongwen’s personal background overshadow his culpable conduct and the suffering of the victims – the Chamber wishes to emphasise this point again in the strongest terms. Nevertheless, the specificity of his situation cannot be put aside in deciding whether he must be sentenced to life imprisonment for his crimes.[124]

The Chamber sentenced Ongwen to twenty-five years imprisonment, and, as previously noted, Judge Raul C. Pangalangan filed a Partially Dissenting Opinion stating that he believed a thirty-year sentence was deserved.[125]

The choice to consider Ongwen’s history as a child soldier at sentencing, when viewed alongside the Chamber’s dismissal of claims regarding a 31(a) defense, creates a muddled view of the decision. During his trial, Ongwen’s abduction and childhood were ignored mainly due to the egregious nature of his conduct. Meanwhile, during sentencing, this history apparently played a significant role in the Chamber’s choice not to pursue the maximum allowed. It seems counterintuitive not to consider it more holistically during all trial phases.

From a practical perspective, the Court’s dismissal of the Article 31(a) defense regarding mental disease or defect formed due to Ongwen’s forced abduction[126] appears to have occurred primarily because of failures committed by the Defense’s expert witnesses. Yet, despite errors by the two physicians in question, the Chamber evidently saw past those errors during sentencing.

A question that arises is whether, if during its contemplation of an appropriate sentence, the Chamber was moved to consider the way that Ongwen’s abduction influenced his actions, why did it not also consider his childhood when considering his legal culpability and his ability to form the necessary mens rea for the crimes committed? If the expert testimony dismissed by the Chamber was insufficient to affect the decision on the charges, arguably, it had no place playing a role in the sentencing.

6. Conclusion

Reflecting upon the issues raised in Ongwen, this paper proposes that—when dealing with former child soldiers who are both victims and perpetrators—courts should consider crimes directly involved with warfare more holistically than crimes relating to SGBV. In effect, courts should bifurcate such cases and assess liability and defenses through a different lens based on the charges.

The Ongwen court started down this path when it decided that “the charges [could] be sub-divided into three main categories.”[127] The Chamber arguably recognized that the types of crimes committed in military attacks against the four IDP camps were different than the charges concerning SGBV directly perpetrated by Ongwen and other SGBV for which he did not directly perpetuate but for which he was still responsible.[128]

Drawing lines between military-related crimes and SGBV would also allow prosecutors to better navigate the troubled waters of cases like Ongwen’s, where a zero-sum[129] game of “child soldier” or “not child soldier” leads both prosecution and defense to ignore many subtleties that should be considered in the general pursuit of justice.[130] Such binaries are disruptive. If the Court is to cede that victim turned perpetrator is forever a victim, then those demanding justice against the new perpetrator shall never have their day. Meanwhile, if no consideration can be made of a childhood filled with violence and manipulation, then there is no justice for the child kidnapped against their will and coerced into becoming a killing machine.[131] Neither result should be acceptable.

Ongwen’s case includes details that support a proposition regarding the differentiation between military criminal acts and sexual/gender-based criminal acts. While it is incontrovertible that Ongwen learned extreme violence in warfare through his childhood indoctrination, his attitudes towards sexual relations appear less influenced.

Ongwen’s understanding of this realm is most clearly demonstrated through the juxtaposition of his treatment of different groups of women. For example, he “‘permitted’ several of his concubines to escape with his many children,” and one of his former “wives” was among those calling for him to be granted amnesty.[132] That wife, Florence Ayot, stated that Ongwen loved her son like his own children by other wives, was never “quarrelsome,” and had lived happily together.[133] However, this depiction of an apparently kind husband and father is in stark contrast to the testimony of those like P-227, one of Ongwen’s eight direct victims, who explained in graphic detail Ongwen’s vaginal and anal rape of her at gunpoint.[134]

Such disparate behavior suggests that when considering SGBV, Ongwen may have understood right from wrong as well as the desires and wants of those sexually victimized at his hands. This argument was supported by the testimony of the Prosecution’s expert witness, Dr. Gillian Clare Mezey, who noted that the evidence she examined demonstrated Ongwen generally had a sense of “moral awareness or an awareness of the difference between right and wrong.”[135]

This disputes the idea that his childhood abduction must be taken into consideration when deciding on culpability for actions related to SGBV. The psychological processes that turned the child Ongwen into a ruthless and violent military commander—one who may have truly believed that his forms of warfare were legitimate—may not have completely shattered his understanding of normal sexual and romantic relations. Thus, at some level, he may have known that at least those actions were wrong and should be culpable.

However, the idea that a victim-perpetrator’s responsibility for SGBV cannot be mitigated by their childhood abduction does not mean that their responsibility for other types of crimes cannot be mitigated. This fact is particularly applicable when it comes to situations like Ongwen’s, where war-related crimes are closely linked to the circumstances of his abduction and the types of acts he was forced to commit as a child.

Treating SGBV charges in cases like Ongwen’s differently from those related to military attacks would serve three purposes. First, by creating a differentiation, those whose backgrounds may necessitate that courts consider their history as victim-perpetrators could still be held strictly responsible for SGBV while having military-related crimes viewed through a lens that takes into consideration the military indoctrination they began at young ages. Second, by placing SGBV in a category where even mental defect and childhood brainwashing provide no defense, it would reinforce the fact that SGBV needs to be considered among the most heinous taboos in armed conflict, ensuring that future cases are presented with clear precedent condemning SGBV and demonstrating the ICC’s dedication to taking SGBV seriously. Lastly, with two distinct paths, prosecutors could demonstrate an unwavering commitment to getting justice for victims of SGBV while also showing compassion for defendants who were, at one point, victims.

Admittedly, this framework—where Ongwen would effectively face two trials—could have resulted in a total Article 31(a) defense on warfare-related crimes while still resulting in life imprisonment for SGBV crimes. On its face, the fact that a harsher sentence could occur may appear as a miscarriage of justice. However, it would more holistically evaluate a defendant for culpability. Such a result would help future courts avoid the pitfalls of having to choose absolutely whether to take into consideration a victim-perpetrator’s history as a child soldier. It would promote justice, not just for the obvious victims, but also for the child who was manipulated, threatened, and coerced into committing horrible crimes at the behest of others. Effectively, in a situation too complex for a simplistic approach, it would use two sets of properly calibrated scales instead of a single one through which a zero-sum calculation of guilt is necessary.

*Zej Moczydłowski

J.D. Candidate, Washington University School of Law (WashU Law); Sergeant First Class and Special Operations Combat Medic, U.S. Army Reserves. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Army, U.S. Special Operations Command, U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

[1] The phrases “sexual and gender-based violence” (SGBV), “sexual and gender-based crimes” (SGBC), and “gender-based violence” (GBV) are all used, somewhat interchangeably, to reference the types of acts committed by Dominic Ongwen, the LRA, and similar individuals and groups. First, this paper uses SGBV rather than SGBC because, in a conversation regarding charges, calling something a crime at the outset may inadvertently cast an assumption of guilt upon the accused. Second, while the ICC Office of the Prosecutor is correct when it calls for a “gender perspective,” the exclusion of sexuality in “GBV” dismisses the way that such violence is often rooted in carnal desires pursued through violent, illegal, and non-consensual acts. When illegal conduct is rooted in the pursuit of sexual dominance and/or gratification, minimizing that particular aspect of the acts is to arguably—and incorrectly—ignore part of the motivation for their commission. See Office of the Prosecutor, Policy on Gender-Based Crimes, ICC-OTP (Dec. 2023), https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/2023-12/2023-policy-gender-en-web.pdf (“Gender perspective refers to the understanding of differences in status, power, roles, and needs between men and women, including/and LGBTQI+ persons, and how gender inequality and discrimination on the basis of sex, gender identity or sexual orientation may impact people’s opportunities, interactions, and experiences in a given context. This understanding includes an awareness of how gender-related norms can vary within and across contexts”).

[2] Fact Sheet Counter Lord’s Resistance Army (C-LRA), ReliefWeb (Sept. 16, 2016), https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/fact-sheet-counter-lord-s-resistance-army-c-lra.

[3] Prosecutor v. Kony, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/05, Document Containing the Charges, ¶¶ 3–4 (Jan. 19, 2024).

[4] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15A, Appeals Judgment, ¶ 51 (Dec. 15, 2022).

[5] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶ 12 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[6] Id. at ¶¶ 13–14.

[7] Julia Brown, When Children are Trained to Kill: A Look at the Victim-Perpetrator Debate in the United States and Uganda, 38 Ariz. J. Int’l & Comp. Law 375, 376 (2022).

[8] Id. at ¶¶ 26–29.

[9] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Public Redacted Version of Corrected Version of Defence Closing Brief, ¶ 569 (Mar. 13, 2020).

[10] See Prosecutor v. Kony, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/05, Document Containing the Charges, ¶¶ 88–91 (Jan. 19, 2024).

[11] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶¶ 1014–16 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[12] Id. at ¶ 38.

[13] Id. at ¶ 15.

[14] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Report of the Registry on the Voluntary Surrender of Dominic Ongwen and His Transfer to the Court, ¶¶ 1–3 (Jan. 22, 2015).

[15] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶ 15 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[16] Charles A. Taku & Beth S. Lyons, The Ongwen Judgments: A Stain on International Justice, J. Int’l Crim. L. 1, 1–2 (2024) [hereinafter Taku & Lyons].

[17] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, supra note 15, at ¶ 16.

[18] Id. at ¶ 32.

[19] Taku & Lyons, supra note 16, at 2.

[20]See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, supra note 15 at ¶ 10.

[21] Id. at ¶ 34.

[22] Id. at ¶ 35.

[23] Id. at ¶ 36.

[24] Counts 69–70 related to the conscription and use of children under the age of fifteen years and their use in armed hostilities but are also not relevant to this paper.

[25] Marina Kumskova, Invisible Crimes Against Humanity of Gender Persecution: Taking a Feminist Lens to the ICC’s Ntaganda and Ongwen Cases, 57 Tex. Int’l L.J. 239, 241 (2002).

[26] Q&A: The LRA Commander Dominic Ongwen and the ICC, Hum. Rts. Watch (Jan. 27, 2021), https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/01/27/qa-lra-commander-dominic-ongwen-and-icc [hereinafter Human Rights Watch].

[27] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Public Redacted Version of Corrected Version of Defence Closing Brief, ¶ B(i) (Mar. 13, 2020).

[28] Id.

[29] Taku & Lyons, supra note 16, at 4.

[30] Prosecutor v. Kony, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/05, Document Containing the Charges, ¶ 11 (Jan. 19, 2024).

[31] In session, the 16th Annual International Humanitarian Law Roundtable considered this issue at length. Ultimately, all parties in the debate appeared to agree that any attempt at an affirmative defense due to mental duress would have failed because, by the time of his surrender, Ongwen no longer faced the proverbial “gun to the head” required to demonstrate a fear of imminent retaliation against an individual who disobeyed their commander.

[32] Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court art. 31(a), July 17, 1998, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.183/9 [hereinafter Rome Statute].

[33] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Public Redacted Version of Corrected Version of Defence Closing Brief, ¶ 546 (Mar. 13, 2020).

[34] Id. at ¶ 537.

[35] Id. at ¶ 522.

[36] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15A, Appeals Judgment, ¶ 1119 (Dec. 15, 2022).

[37] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶ 2527 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[38] Id. at ¶ 2531.

[39] Id. at ¶ 2527.

[40] Id. at ¶ 2533.

[41] Id. at ¶ 2545.

[42] Id. at ¶ 3116.

[43] Id.

[44] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Sentence, ¶ 386 (May 6, 2021).

[45] Id. at ¶ 388.

[46] Id. at ¶ b.

[47] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15A, Partly Dissenting Opinion of Judge Raul C. Pangalangan, ¶¶ 16–19 (May 6, 2021).

[48] Id. at ¶ 15.

[49] See Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15A, Appeals Judgment, ¶ 1277 (Dec. 15, 2022).

[50] Id.

[51] Id. at ¶¶ 1685–87.

[52] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15A2, Judgment on the Appeal of Mr. Dominic Ongwen Against the Decision of Trial Chamber IX of 6 May 2021 Entitled “Sentence”, ¶ 373 (Dec. 15, 2022), (Judge Ibáñez Carranza partly dissented on one ground of appeal—the allegation of double-counting the factor of a multiplicity of victims—and would have reversed the twenty-five-year sentence and remanded to the Trial Chamber for it to determine a new sentence).

[53] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Reparations Order, ¶ 795 (Feb. 24, 2024).

[54] Jonathan Gottschall, Explaining Wartime Rape, 41 J. Sex Rsch. 129, 130 (2004).

[55] Nicola Henry, Theorizing Wartime Rape: Deconstructing Gender, Sexuality, and Violence, 30 Gender and Soc’y 45, 45 (2016).

[56] Julia Tétrault-Provencher, Replicating the Definition of ‘Forced Pregnancy’ from the Rome Statute in a Future Convention on Crimes Against Humanity: A Tough Pill to Swallow, 33 Hastings Women’s L.J. 105, 107 (2022) [hereinafter Tétrault-Provencher].

[57] Jocelyn Campanaro, Women, War, and International Law: The Historical Treatment of Gender-Based War Crimes, 89 Geo. L.J. 2557, 2562 (2001) [hereinafter Campanaro].

[58] Janet Halley, Rape at Rome: Feminist Interventions in the Criminalization of Sex-Related Violence in Positive International Criminal Law, 30 Mich. J. Int’l L. 1, 43–44 (2008).

[59] Id. at 44.

[60] See Campanaro, supra note 57, at 2564.

[61] Kelly D. Askin, Prosecuting Wartime Rape and Other Gender-Related Crimes under International Law: Extraordinary Advances, Enduring Obstacles, 21 Berkeley J. Int’l L. 288, 288 (2003) [hereinafter Askin].

[62] Dianne Luping, Prosecuting Sexual and Gender-Based Crimes Before Internationalized Criminal Courts: Investigation and Prosecution of Sexual and Gender-Based Crimes Before the International Criminal Court, 17 Am. U.J. Gender Soc. Pol’y & L. 431, 440 (2009) [hereinafter Luping].

[63] Id. at 445.

[64] Id.

[65] See Askin, supra note 61, at 317.

[66] Prosecutor v. Gagovic, Case No. IT-96-23-1, Indictment (Jun. 26, 1998).

[67] See Luping, supra note 62, at 446.

[68] Id.

[69] Prosecutor v. Akayesu, Case No. ICTR-96-4-T, Judgement (Sep. 2, 1998).

[70] See Askin, supra note 61, at 318.

[71] Tanja Altunjan, Sexual Violence in International Criminal Law: The International Criminal Court and Sexual Violence: Between Aspirations and Reality, 22 German L.J. 878, 878 (2021) [hereinafter Altunjan].

[72] Id. at 881.

[73] Id. at 878.

[74] Prosecutor v. Ntaganda, Case No. ICC-01/04-02/06, Judgment (Jul. 8, 2019).

[75] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment (Feb. 4, 2021).

[76] See Altunjan, supra note 71, at 884.

[77] Rosemary Grey, Gender and Judging at the International Criminal Court: Lessons from “Feminist Judgment Projects”, 34 Leiden J. of INT’L L. 247, 252 (2021) [hereinafter Grey].

[78] See Office of the Prosecutor, Policy on Gender-Based Crimes, ICC-OTP (Dec. 2023), https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/2023-12/2023-policy-gender-en-web.pdf.

[79] Prosecutor v. Lubanga, Case No. ICC-01/04-01/06, Judgment (Mar. 14, 2012).

[80] See Grey, supra note 77, at 258.

[81] Id.

[82] Ally McQueen, Falling Through the Gap: The Culpability of Child Soldiers Under International Criminal Law, 94 Notre Dame L. Rev. Reflection 100, 103 (2019) [hereinafter McQueen].

[83] Eben Kaplan, Child Soldiers Around the World, Council on Foreign Rels. (Dec. 2, 2005), https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/child-soldiers-around-world [hereinafter Kaplan].

[84] See Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) art. 77(2), June 8, 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 3. See also Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II) art. 4(2)(c), June 8, 1977, 1125 U.N.T.S. 609.

[85] Cape Town Principles, U.N. Int’l Child.’s Emergency Fund (Apr. 30, 1997).

[86] G.A. Res. 54/263 (Mar. 16, 2001).

[87] See McQueen, supra note 82, at 115.

[88] U.N. Secretary General, Report of the Secretary General on the Establishment of a Special Court for Sierra Leone, U.N. Doc. 2/2000/915 (Oct. 4, 2000). See also, McQueen, supra note 83 (noting Secretary General Annan would go on to state that the court “would not necessarily exclude persons of young age from [its] jurisdiction.” However, the Prosecutor for the Court, David Crane, “quickly made it very clear that he would never prosecute anyone under the age of eighteen”).

[89] See McQueen, supra note 82, at 124.

[90] Id.

[91] Id.

[92] Handbook on Children Recruited and Exploited by Terrorist and Violent Extremist Groups: The Role of the Justice System, U.N. Off. on Drugs & Crime (2017).

[93] Omar Khadr Charge Sheet, United States v. Khadr, 717 F. Supp. 2d 1215 (U.S.C.M.C.R. 2007), https://www.mc.mil/Portals/0/pdfs/Khadr/Khadr%20(AE001).pdf.

[94] Jennifer Turner, Pentagon Admits Number of Guantánamo’s Children is Higher than Originally Disclosed, ACLU (Nov. 17, 2008), https://www.aclu.org/news/national-security/pentagon-admits-number-guantanamos-children-higher-originally.

[95] Khadr’s case shows how the U.S. approach to child combatants or soldiers differs from international consensus because the U.S. appears to use the age of sixteen as the line of demarcation between a child and an adult for these purposes. Other juvenile combatants under the age of sixteen captured during U.S. operations in the same time frame were sent to Camp Iguana, accommodated separately from adults, and received not only schooling but also group therapy sessions. “The only reason for the difference between their and Khadr’s treatment . . . is that Khadr was only transferred to Guantanamo after his sixteenth birthday, despite the fact that he was originally detained when he was fifteen years of age.” See also Matthew Happold, Child Soldiers: Victims or Perpetrators?, 29 U. La Verne L. Rev. 56, 86 (2008).

[96] See Kaplan, supra note 83.

[97] See McQueen, supra note 82, at 101.

[98] Human Rights Watch, supra note 27.

[99] U.S. v. Alexander, 471 F.2d 923 (D.C Cir. 1973) (Bazelon, C.J., dissenting).

[100] Richard Delgado, Rotten Social Background: Should the Criminal Law Recognize a Defense of Severe Environmental Deprivation, 3 Minn. J.L. & Inequality 9, 20–21 (1985). See also U.S. v. Alexander, 471 F.2d 923, 961 (D.C Cir. 1973) (Bazelon, C.J., dissenting).

[101] Taku & Lyons, supra note 16, at 9.

[102] Id. at 10.

[103] Rome Statute, supra note 32, art. 21(2) (stating that the Court may—not must—”principles and rules of law as interpreted in its previous decisions”).

[104] Prosecutor v. Lubanga, Case No. ICC-01/04-01/06, Judgment (Mar. 14, 2012).

[105] Layal Issa, Avoiding the Third Tragedy: Evaluating Criminal Responsibility of Child Soldiers Under International Law, 34 Temp. Int’l & Comp. L.J. 61, 73–74 (2020).

[106] Mark A. Drumbl, Victims Who Victimise, 4 London Rev. Int’l L. 217, 242 (2016) [hereinafter Drumbl].

[107] Raphael L. A. Pangalangan, Dominic Ongwen and the Rotten Social Background Defense: The Criminal Culpability of Child Soldiers Turned War Criminals, 33 Am. U. Int’l L. Rev. 605, 619–20 (2018).

[108] Luping, supra note 62, at 445.

[109] See Grey, supra note 77, at 260.

[110] Id. at 261.

[111] Id.

[112] Id. at 263.

[113] See Tétrault-Provencher, supra note 57, at 114.

[114] Rome Statute, supra note 32, art. 7(1)(g).

[115] Id. at art. 7(2)(f).

[116] See generally Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶ 12 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[117] See Tétrault-Provencher, supra note 57, at 132.

[118] Id. at 133.

[119] Id.

[120] Meaning of ‘Confine’ in English, Cambridge Dictionary, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/confine.

[121] Mark A. Drumbl, A Former Child Soldier Prosecuted at the International Criminal Court, OUP Blog (Sep. 26, 2016), https://blog.oup.com/2016/09/child-soldier-prosecuted-icc-law/.

[122] Taku & Lyons, supra note 16, at 3.

[123] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶ 2580 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[124] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Sentence, ¶¶ 388–89 (May 6, 2021).

[125] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15A, Partly Dissenting Opinion of Judge Raul C. Pangalangan, ¶¶ 16–19 (May 6, 2021).

[126] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Public Redacted Version of Corrected Version of Defence Closing Brief, ¶ 536 (Mar. 13, 2020).

[127] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Judgment, ¶ 33 (Feb. 4, 2021).

[128] Id.

[129] Drumbl, supra note 106.

[130] Id. at 242 (“If the defence presents Ongwen only as an innocent child, and the prosecution responds by redlining the fact that Ongwen had entered the LRA as a child and came of age in such a dismal setting, then the result will be to embed the binaries even further”).

[131] See Drumbl, supra note 106, at 217.

[132] Id. at 238.

[133] Dominic Ongwen: From Child Abductee to LRA Rebel Commander, BBC (May 6, 2021), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30709581.

[134] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Confirmation of Charges (Transcript), 41–42 (Jan. 1, 2016), https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/Transcripts/CR2016_02436.PDF.

[135] Prosecutor v. Ongwen, Case No. ICC-02/04-01/15, Trial Hearing (Transcript), 47 (Mar. 19, 2018), https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/Transcripts/CR2018_04200.PDF.

Cover image credit

Apr 11, 2025 | Online Scholarship, Perspectives

*Piotr Filip Parkita

I. Potential for colonizing Mars

In May 2024, Małgorzata Polkowska published an interesting article about projects for colonizing Mars and other celestial bodies. Special attention should be given to the legal considerations she offers within the framework of contemporary space law doctrine. The international community currently lacks adequately constructed legal regulations that would comprehensively address this subject. Denis Safronov, a Russian researcher, highlighted how the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST) fails to account for the legal challenges arising from the exploration of space. There is indeed a legal gap in this area. The laws enacted in the last century are not adequate to address the challenges of modern industry and the ambitions for space development. The international community should take steps to regulate this issue.

The colonization of Mars is not a distant concept; it should be considered realistically. Mars possesses numerous resources that might facilitate human colonization. The existence of water ice is essential for supplying drinking water as well as agricultural purposes. Additionally, water can be separated into hydrogen and oxygen. These elements are vital for rocket fuel and breathing. Polkowska, for example, cited the ongoing Artemis program, which is an exciting step in human’s journey to Mars (this program is being implemented by NASA, ESA, and JAXA, among others). Artemis consists of several key elements that are expected to play a crucial role in the success of the mission, including the expansion of the Gateway station and the establishment of the Artemis Base Camp on the lunar surface.

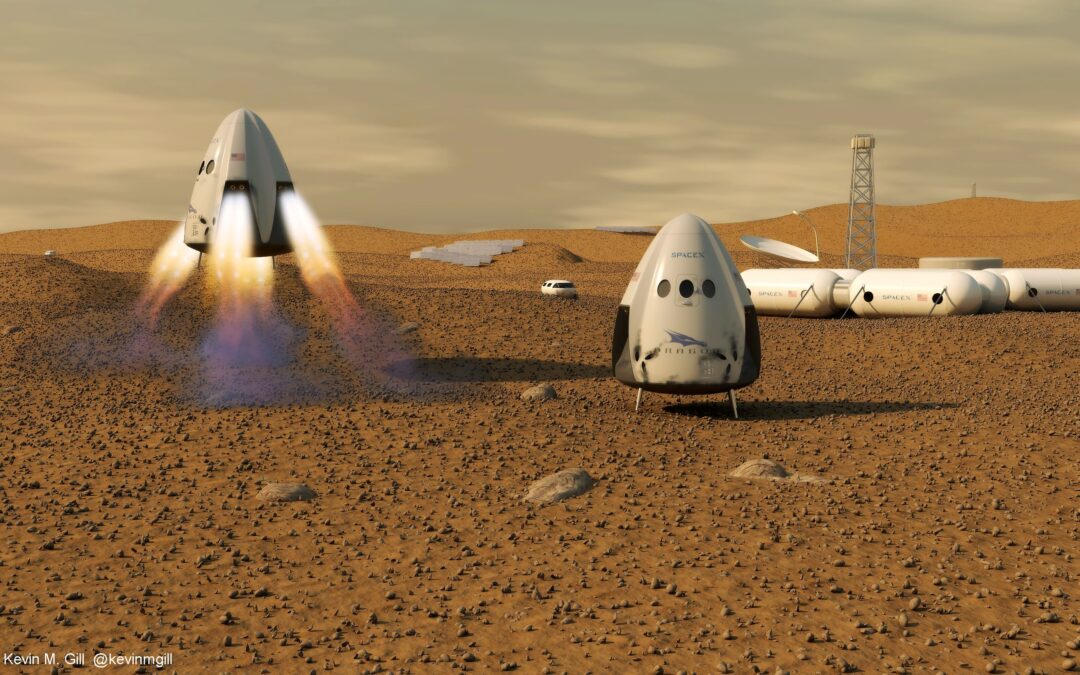

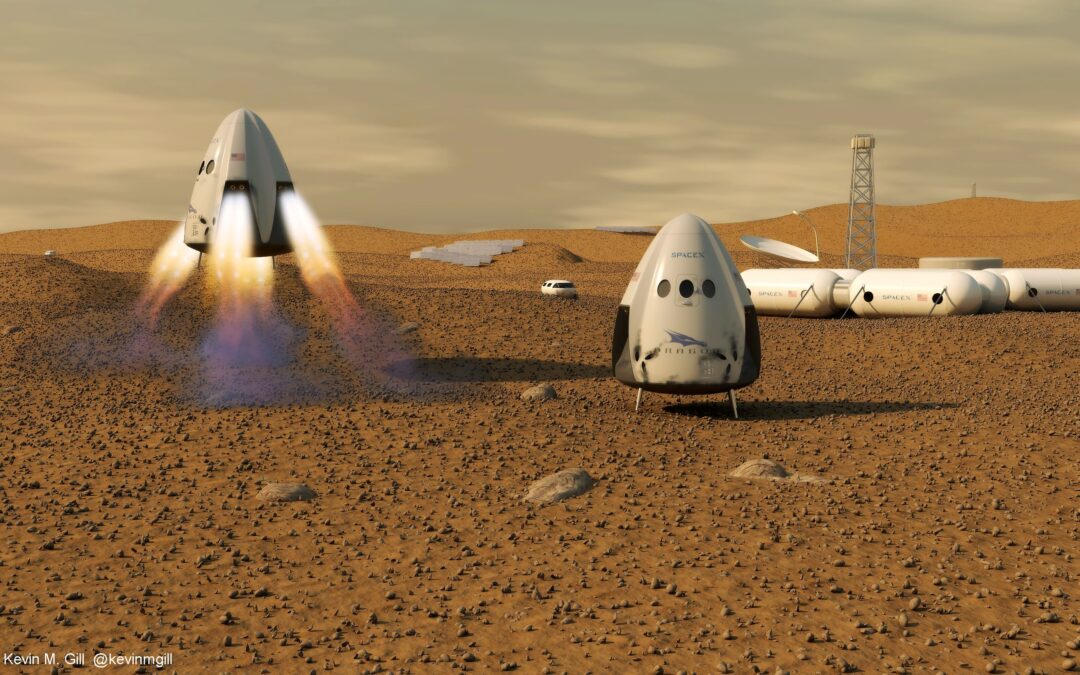

Private enterprises are intimately involved in this domain: Elon Musk, the CEO of SpaceX, projected in 2022 that his company’s inaugural manned mission to Mars might commence as soon as 2029. These plans presently seem rather ambitious. However, it is evident that the concept of colonization continues to captivate the imagination, presenting an escalating array of challenges to humanity. One of these challenges is the accurate legal classification of such activities, which necessitates a robust regulatory framework specifically addressing these ventures. Abu Rayhan noted that while “significant technological, health, ethical, and legal hurdles remain, ongoing advancements and international collaboration could make human settlement of other planets a reality in the coming decades.”

II. Problems arising from the Outer Space Treaty

Given the accelerating advancement of entities within the space industry, including those collaborating with governmental agencies, it is essential to formulate appropriate legal frameworks to facilitate the objective categorization of these activities. These entities are subject to the jurisdiction of multiple nations, which complicates the process of achieving legal harmonization. The legal regime governing the potential colonization of Mars is regulated by the OST. Other legal acts related to outer space include the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space, also referred to as the Rescue Agreement. These instruments are intended to ensure the peaceful exploration and use of outer space.

The OST is a legal instrument adopted in 1967, with 115 states as its parties. It failed to consider the issues that would arise from rapid technological advancement and the increasing presence of activities such as space tourism. Despite the fact that Mars colonization is a plausible concept that could become a reality in the near future (within the next decades or so), I refer to it as the “tomorrow for which we are not prepared.” The OST, in its current form, is not equipped to regulate actions supporting the concept of Mars colonization, which is increasingly emerging within the international community. A thorough analysis of the articles of this document (I, II, VI, VIII, IX) is necessary.

As John Clayton rightly notes, nations can withdraw from the OST with a one-year notice period, after which they are no longer constrained by the provisions of this legal instrument. This would allow states to make claims over certain areas of outer space and use them according to their national interests without restriction. Such an option appears particularly advantageous for countries with superior technological and budgetary resources, especially P5 countries on the UN Security Council. Opposition to their actions would likely be ineffective, given that the strategic advantages of space exploitation would surpass any temporary negative effects on these countries’ international relations. The P5 countries vested with veto power on the UN Security Council are China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America — leading players in the space race with equipment and technology far more advanced than those of other treaty members.

Thus, it is necessary to develop appropriate solutions that can secure the interests of smaller nations with less advanced technology in the future, allowing them to participate on more even footing in space colonization.

III. The premises undergirding colonization in the context of the Outer Space Treaty

Article I of the OST establishes a fundamental principle for the exploration and use of outer space: all such activities “shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.” This principle implies that any benefits derived from activities in outer space, including those associated with colonization or the establishment of human settlements on celestial bodies like Mars, must be shared equitably. The concept of “the province of all mankind” emphasizes that outer space is a domain where no state or entity can claim exclusive rights to the fruits of exploration, thus framing space as a collective heritage and resource.

This principle introduces a critical constraint: colonization must be universally advantageous, accessible to all countries, and cannot be exploited solely for the individual benefit of the state or private entity that initiates such efforts. This stipulation directly opposes the historical model of Earth-based colonization, where the colonizing power often derived unilateral benefits, primarily through the extraction of natural resources and the establishment of exclusive economic zones. Any space colonization must adhere to a model that prioritizes shared benefits, consistent with the spirit of global cooperation embedded in the OST.

From this perspective, the logical approach to space colonization would be through collaborative missions involving multiple countries, all of which are parties to the OST. Such joint endeavors would help ensure that the outcomes of space exploration and resource use align with the principle of the common good. Collaborative missions would facilitate the sharing of technology, scientific knowledge, and resources, thereby minimizing the risk of any single state monopolizing the advantages of space colonization.

However, the practical realization of these principles presents challenges, especially when considering the concept of terra nullius. While Mars qualifies as terra nullius (nobody’s land) under international law, the limited and non-renewable nature of its resources could eventually lead to competition and exclusive claims by states or private entities that undertake colonization efforts.

Furthermore, the historical context of Earth-based colonization demonstrates a pattern of competitive exploitation of natural resources and territory. Although space colonization differs fundamentally — given the absence of indigenous human populations and the unique legal status of outer space — the risk remains that individual states may seek to secure preferential, or worse yet, exclusive access to Martian resources in the long term. This could manifest through the construction of infrastructure, the establishment of research stations, or through long-term resource extraction activities. Such actions, if not carefully regulated, would be at odds with the cooperative framework required by Article I of the OST.

Therefore, any approach to space colonization must not only focus on technical feasibility and scientific advancement but also address these legal and ethical considerations. It must balance the interests of pioneering states with those of the broader international community, maintaining compliance with the OST’s overarching goal of ensuring that space remains a domain where benefits are equitably shared and where activities are conducted for the collective good of humanity.

A possible solution would be the introduction of a separate legal act defining the scope and possibility of claims, similar to the approach taken in the case of Antarctica, where such arrangements were adopted for a specific period. Initially, potential Martian colonies can be similar in concept to polar stations, such as the President Eduardo Frei Montalva Base, along with the inhabited outpost Villa Las Estrellas, which the Chilean government considers as part of the commune Antártica (“commune” being the smallest administrative subdivision in Chile), and thus, de facto, a part of Chilean territory. It should be noted, however, that in the case of the Antarctic Treaty, no prohibition of claims was included. In fact, this treaty somewhat “suspended in time” the claims that had already been made, for the duration of the agreement.

Particularly important is Article II of the OST: “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” This article is arguably the most problematic in this regard. A colony is a territory controlled by an independent country, but considered part of that country for relations with other countries. A colony is a territory under the jurisdiction of an independent state that maintains a relationship with that state. Puerto Rico offers a contemporary example, as it holds the status of an unincorporated territory and serves as a dependent territory of the United States.

Colonization of Mars, by its inherent definition, would inherently contradict the stipulations of Article II of the OST. Even if the colony were to lack sovereignty, or if a country were to establish a Martian colony without asserting sovereignty or national jurisdiction, it would be difficult to argue that this would not meet the threshold of “use” or “occupation” per the treaty. The establishment of a permanent or semi-permanent human settlement on Martian soil would inevitably involve the utilization of land, resources, and potentially infrastructure development, thus creating a conflict with the Article’s text.

Theoretically, establishing and maintaining a colony does not necessarily imply the appropriation of a given territory by a single state — one can look at the issue of oil platforms on the high seas, which are not subject to appropriation according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. It is only the activities of a state concerning such a colony that may raise objections, for instance, if a state were to declare a Martian colony as its extraterrestrial territory.

While a colony may not constitute a direct claim of sovereignty by a nation-state, its presence might still be seen as an indirect exercise of control or jurisdiction, thus conflicting with the non-appropriation principle enshrined in the OST. The ambiguity in the phrase “by any other means” further complicates this interpretation, as colonization could encompass a wide range of activities beyond traditional state claims, potentially including private or corporate initiatives that result in sustained presence or control over specific areas on Mars. This raises significant legal questions regarding the compatibility of a Martian colony with the OST’s intent to preserve outer space as a domain free from national appropriation and exploitation.

According to Article VI of the OST, “States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty.” States are further responsible for the activities of private entities under their jurisdiction, meaning that private colonization cannot serve as a viable solution.

This legal framework implies that even if a private company or entity attempts to establish a colony on Mars, the state under whose jurisdiction that entity operates would still be liable for ensuring that their activities adhere to international space law. Thus, a state’s obligations under the OST cannot be circumvented through privatization or the delegation of space activities to non-state actors. The responsibility extends to supervising and authorizing the activities of private actors to ensure that their actions do not amount to prohibited appropriation or occupation of outer space, thereby maintaining compliance with the non-appropriation principle of Article II.

It is additionally essential to refer to Article VIII: “A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body. Ownership of objects launched into outer space, including objects landed or constructed on a celestial body, and of their component parts, is not affected by their presence in outer space or on a celestial body or by their return to the Earth…” This Article outlines the principle of exercising jurisdiction over an object placed (constructed) on a celestial body, such as Mars. A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, while it is in outer space or on a celestial body, as well as ownership of objects that have been constructed on a celestial body. This may refer to constructions (objects, buildings) built on a celestial body that are significant for the colony.

Moreover, a State Party to the Treaty retains jurisdiction and control over the personnel aboard an object launched into outer space when it is in outer space or on a celestial body. This raises the issue of colonists and their legal status. The problem arises when colonists come from different countries with varying legal systems. It is undeniable that people living together, tasked with building the foundations of a Martian society, may, for instance, commit certain types of crimes or find themselves in civil law conflicts. Transporting such individuals back to the Earth solely for conducting a trial would be impossible. Given the differences in legal systems, it would be worth considering the establishment of a common Martian legal system and laying the groundwork for a jurisdictional apparatus that allows for the swift and efficient resolution of legal disputes among colonists. The considerations regarding the status of a colonist can be narrowed to three main points.

First, the regulation of the status of colonists based on Article V of the OST involves adopting the definition of a colonist as an “envoy of mankind” (similar to astronauts), thereby obligating colonists from different State Parties to provide all possible assistance to colonists from other State Parties.

Second, developing a separate regulation of the status of colonists, by creating an individual legal definition would allow for the introduction of a universally accepted law intended to apply on Mars, effectively making the colonists “citizens of Mars,” subject to those planetary laws. However, this would require the creation of a quasi-state apparatus, entirely under the authority of the United Nations. This apparatus would be responsible for overseeing the administration of laws. Additionally, it would need to foster cooperation among various State Parties to ensure that the legal system is equitable and respects the rights of all colonists, regardless of their country of origin.

Third, the complete lack of regulation on this matter creates a significant legal gap, leaving important questions unresolved. This approach may be seen as appropriate, as it allows for flexibility in adapting legal frameworks to the evolving nature of Mars colonization. Defining the status of colonists too rigidly could be problematic, given the diversity of legal systems involved and the complex, shifting circumstances of space exploration. By leaving a legal gap, the international community can avoid prematurely imposing restrictive laws that might not align with future developments. Additionally, it helps preserve the sovereignty of individual states and protects against overly centralized definitions that could lead to conflicts. This open-ended approach allows for a gradual and more inclusive development of a legal system as the colonization process progresses.

The OST’s limitations also arise from Article IX, which underscores the obligations of states in the exploration and use of outer space. According to Article IX, states must adhere to the principles of cooperation and mutual assistance, ensuring that their activities are carried out with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties to the Treaty.” This provision implies a duty to consider the interests and rights of other states during space activities, including on celestial bodies like Mars.

Moreover, Article IX emphasizes the necessity of avoiding “harmful contamination” of outer space and preventing “adverse changes in the environment of the Earth” that could result from the introduction of extraterrestrial matter. States are thus required to take measures to avoid activities that might harm the space environment or impact the Earth’s ecosystem. This provision suggests that any activity, including colonization or extensive use of Martian resources, must be conducted in a manner that does not jeopardize the integrity of the Martian environment or lead to negative consequences for the Earth.

Additionally, this provision mandates that states engage in “appropriate international consultations” if they believe that their activities, or those of their nationals, could cause “potentially harmful interference” with the activities of other states. This requirement further complicates the prospect of private or unilateral colonization efforts, as it requires transparency and collaboration with the international community to avoid conflicts or interference with the peaceful exploration and use of outer space by other states. If a state believes that another state’s planned activities may be harmful, that state has the right to request consultations, ensuring that potentially disruptive actions are subject to international scrutiny before proceeding.