Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Chad Patrick Osorio*

I. Introduction

The intersection of art and wildlife conservation raises critical questions about the role of cultural expression in addressing environmental challenges. Art has historically depicted nature and human-wildlife interaction, illustrating the connection between humans and the natural world. It has also, however, inadvertently contributed to the illegal wildlife trade (IWT), particularly when art has increased the social acceptability and desirability of owning and hunting wildlife. Examples include Leonardo da Vinci’s The Lady with an Ermine (c. 1489–1490), Peter Paul Ruben’s The Tiger Hunt (c. 1615–1616), and Jacques-Laurent Agasse’s The Nubian Giraffe (c. 1767–1849). Additionally, wildlife products have been used in the creation of art, including plant and animal dyes for paintings and textiles, as well as wood, bone, and horns for ornamentation, trinkets, and sculptures. Both examples are evident in the artistic traditions of Southeast Asia.

(Images are provided by the author)

Southeast Asian art, both past and present, richly incorporates depictions of and references to wildlife. Examples of this include illustrations from Thai horoscope manuals in the 1800s, an early deity carving from ivory, and an antique Balinese rosewood sculpture of a mythical beast, among many others. These artworks resonate with the region, which is home to some of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems and harbors iconic species like tigers, elephants, and hornbills. These species are not only ecologically significant but also hold deep cultural value. However, this rich biodiversity is under severe threat from the illegal wildlife trade. Despite stringent international conventions such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), IWT remains a multi-billion-dollar industry and one of the most lucrative illegal activities in the world. IWT presents numerous challenges, with wide-ranging impacts that affect both the natural environment and human society. Its consequences are significant and multifaceted, spanning environmental, economic, political, and social dimensions.

Southeast Asian countries serve as crucial source, transit, and destination points for wildlife trafficking. Due to their highly porous borders, rapidly growing middle class, and deeply entrenched cultural practices, these countries face unique challenges in addressing this issue. One contributing factor to the underground wildlife market is that derivative products of flora and fauna are trafficked for use in traditional and contemporary works of art. In this article, we seek to shift this perspective and instead explore how international legal frameworks protecting art can be leveraged to protect wildlife within the regional jurisdiction of the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The article is organized as follows: in Part II, we discuss specific cases of some of the most trafficked wildlife in relation to art, including elephant ivory, hornbill casques, hawksbill tortoiseshells, and rosewood and agarwood timber. We outline the current legal conservation framework in the region, giving examples under both treaty and domestic law in Part III. In Part IV, we propose how existing legal protection for art and heritage within the ASEAN can contribute to wildlife protection, capitalizing on market regulation for sustainability. We conclude, in Part V, with an ASEAN-led sustainable art certification program seeking to increase the joint value of nature in ASEAN art.

II. Art and the Illegal Wildlife Trade

The art market—both legal and illicit—has a long history of using wildlife products. Items such as ivory sculptures, mother-of-pearl inlays, and exotic leather crafts are prized for their aesthetic and cultural value. In Southeast Asia, traditional and religious art often incorporates these materials, creating tension between cultural preservation and wildlife conservation.

One of the most glaring examples of art driving wildlife exploitation is the ivory trade. Ivory, derived from the tusks of elephants, has been used for centuries in carving intricate sculptures, religious artifacts, and decorative items. Ivory carvings are highly sought after for their cultural and aesthetic value, particularly in the historical production of religious figurines. Despite the ban on the international trade of ivory, demand persists, exhibited by high ivory prices in Asia. Poachers and traffickers exploit legal loopholes, smuggling ivory to and from Southeast Asia, where artisans transform them into works of art. This demand contributes significantly to the decline of elephant populations, particularly the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus spp.), which is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Another example is the use of helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) casques in jewelry and ornamental art. Known as “red ivory,” the solid keratin casques are carved into intricate designs that are highly valued in East and Southeast Asia. The helmeted hornbill, native to Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand, faces critical endangerment due to poaching driven by demand for its casques. The species plays a vital ecological role as a seed disperser, and its loss has cascading effects on forest ecosystems. Despite international protections, the helmeted hornbill continues to be targeted, with traffickers smuggling casques through clandestine networks.

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), classified as critically endangered, is another species victimized by the art market. Its tortoiseshell is used to craft jewelry, combs, and decorative items. In the Philippines, tortoiseshell crafts have a long tradition, particularly in coastal communities. The exploitation of hawksbill turtles for art not only threatens their survival but also disrupts marine ecosystems, where they play a role in maintaining coral reef health. The continued demand for tortoiseshells highlights the need for stronger enforcement.

Plants also play a significant role in the illegal trade linked to art. Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.), prized for its deep red hue and durability, is commonly used in furniture and carvings. Rosewood smuggling is a pervasive issue in countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, where forests are stripped of this valuable resource to meet international demand. The exploitation of rosewood for luxury goods has led to deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and illegal logging operations that endanger local communities. Similarly, agarwood (Aquilaria spp.), used in perfumes, incense, and intricate carvings, is overharvested due to its high market value. Native to several ASEAN countries, agarwood trees are now critically endangered in many areas, further threatening forest ecosystems.

These are just some examples of wild flora and fauna, from land, sea, and air, trafficked within Southeast Asia to serve the global demand for art.

III. Legal Frameworks Protecting Wildlife in ASEAN

There are existing legal protections for wildlife in Southeast Asia, led foremost by ASEAN—a regional intergovernmental organization that promotes political and economic cooperation among ten Southeast Asian countries. Founded on August 8, 1967, through the signing of the ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, ASEAN has since grown to include Brunei Darussalam (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos (1997), Myanmar (1997), and Cambodia (1999). ASEAN’s core objectives are to foster regional peace and stability, stimulate economic growth and prosperity, and enhance cooperation among its Member States.

ASEAN places much emphasis on principles such as mutual respect, non-interference, consensus-building, and collaboration. The regional body seeks to ensure that Member States acknowledge each other’s sovereignty and refrain from actions that could undermine national interests or be perceived as external intervention in domestic affairs. Consensus-building is equally central to ASEAN’s decision-making process, requiring unanimous agreement among its members, which ASEAN implements through regular meetings and consultations. Through this cooperative political-legal framework, the regional organization has developed various policies and programs to promote interstate cooperation in trade and investment, regional security, social and cultural matters, and sustainable development. Among its notable accomplishments is the establishment of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which seeks to create a unified market and production base, enabling the free movement of goods, services, investments, and skilled labor within the region. As a result of these efforts, as of 2022, ASEAN has emerged as the fifth-largest economy globally.

ASEAN countries are signatories to various international conventions aimed at curbing illegal wildlife trade. The most significant is CITES, which regulates the international trade of endangered species. This is supported by regional initiatives like the ASEAN Wildlife Enforcement Network (ASEAN-WEN), which facilitates cooperation among Member States to combat wildlife trafficking, providing a platform for sharing intelligence and best practices among enforcement agencies. Similarly, the ASEAN Working Group on CITES and Wildlife Enforcement aligns Member States with CITES requirements and enhances enforcement capabilities.

Each ASEAN country has its own set of laws addressing wildlife conservation and illegal trade. For instance, Thailand’s Wildlife Conservation and Protection Act (2019) criminalizes the possession and trade of protected species and their derivatives. Indonesia’s Law on Conservation of Biological Natural Resources and their Ecosystems (1990), recently updated, includes provisions for wildlife trafficking, imposing penalties for trading endangered species. In the Philippines, the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act (2001) prohibits the exploitation of endangered species for commercial purposes. Despite these frameworks, enforcement challenges persist, including corruption, lack of resources, and inadequate cross-border collaboration. Below is the table of domestic legislation in support of wildlife protection in the ASEAN region.

Table 1. CITES-related Laws in ASEAN Countries

IV. Exploring Legal Synergy between Art and Conservation Law

The question remains: how can art law support these wildlife conservation initiatives? After all, art law is a specialized legal field addressing the creation, ownership, sale, and protection of art, encompassing intellectual property rights, cultural heritage preservation, provenance verification, and market regulation. Nature conservation law, on the other hand, focuses on safeguarding natural resources, biodiversity, and ecosystems, regulating activities like hunting, fishing, logging, and trade to prevent environmental degradation. In this section, we explore how integrating these two domains can offer a promising tool to address the use of wildlife products in art, particularly in the ASEAN region.

One potential initiative involves merging intellectual property protection with eco-labeling certifications. Geographical indications (GIs), which identify products with qualities tied to their origin, could be expanded to certify products as sustainably sourced and wildlife-friendly. This approach, in line with the One Village, One Product campaign led by ASEAN, could protect sustainable wildlife use while fostering community-based practices. This strategy unites conservation, intellectual property, and cultural heritage for a common cause.

As envisioned, the enhanced GI certification would include sustainability and wildlife-friendly practices as core criteria. Commercially available art and heritage products such as textiles, wood carvings, and agricultural goods would need to meet these standards to earn the ASEAN-approved label. This certification scheme would offer significant benefits for wildlife protection. Encouraging alternative sustainable materials and ethical production practices decreases reliance on resources derived from endangered species. The overexploitation of high-value wood carvings could be curtailed through the certification of sustainably sourced wood. Additionally, discouraging the use of endangered wildlife derivatives such as ivory or hornbill casques at the grassroots level supports supply-induced demand reduction of these illegal products.

Moreover, the scheme uplifts community-based approaches by linking sustainability to products deeply rooted in local traditions and indigenous knowledge. Many GI art products reflect cultural identity and heritage. By adopting eco-focused practices and providing government support for alternative wildlife-friendly materials, artisans can act as stewards of both cultural and natural resources, preserving their traditions while supporting conservation. Artisans and woodworkers across the region can integrate sustainable sourcing without compromising their craft’s authenticity. Capacity-building initiatives, such as training artisans on sustainable methods, would strengthen community resilience, protect socio-economic rights, and ensure long-term benefits.

Economic incentives further bolster this approach. Certified products command higher market value, attracting ethical consumers who prioritize sustainability and conservation (a global market enjoying steady market growth). This can create a cycle where increased demand for certified products motivates communities to adopt wildlife-friendly practices, amplifying conservation impacts. At the same time, campaigns can be launched to attach stigmas to art products that are not sustainably sourced. By associating non-sustainably sourced wildlife products with negative social and ethical connotations, campaigns can discourage consumer demand and shift market preferences toward certified alternatives. Public awareness initiatives, celebrity endorsements, and policy interventions can reinforce these stigmas. This helps make unsustainable products less desirable and even socially unacceptable. Over time, such stigmatization can pressure artisans and commercial art producers to transition toward sustainable sourcing practices to maintain market credibility and consumer trust. These campaigns go hand-in-hand with labeling requirements and trade restrictions and make it easier for consumers to distinguish between ethical and unethical products.

Implementing this scheme in Southeast Asia requires careful planning and collaboration among Member States. ASEAN policymakers must set clear standards and enforcement mechanisms. Partnerships with other international bodies as well as academia can provide funding and technical expertise, while community leaders, Indigenous Peoples, and civil society can work together to adapt traditional practices to meet sustainability criteria without losing cultural authenticity.

V. Conclusion

One of the most significant challenges in the use of wildlife in art is balancing cultural preservation with conservation. Traditional art forms that rely on wildlife products must adapt to modern conservation ethics without losing their cultural significance. In line with ASEAN’s goal of a common regional market, facilitating both supply and demand for wildlife-friendly art can incentivize artisans to adopt sustainable practices and influence social norms for wildlife protection. To spearhead this, an ASEAN-led art certification program can help consumers identify and support ethical and environmentally responsible art.

Based on this premise, art law holds immense potential to support the protection of wildlife in the ASEAN region. However, this potential can only be realized through regional cooperation, an integrated legal framework, and community engagement. By aligning the art world with conservation goals, ASEAN can transform a significant challenge into an opportunity for preserving its rich biodiversity and cultural heritage.

*Chad Patrick Osorio is a current PhD Researcher at Wageningen University and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines Los Banos. He thanks Dasha Gretchikine (Wageningen University) for the editorial support and Carl Kristoffer Hugo (University of the Philippines Los Banos) for the research assistance.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

*Anne-Marie Carstens

In early 2025, the Octagon Earthworks, a 2,000-year-old indigenous ceremonial and burial site comprised of earthen geometric structures, opened to the public. The opening came after two parties—the government agency taking possession through eminent domain and the leaseholder that occupied the site—settled the last issue in their drawn-out legal dispute by agreeing on the just compensation owed for the taking. The site forms a crucial part of a collection comprising the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks, which was nominated by the United States in 2022 and selected by the World Heritage Committee for inscription on the international World Heritage List. The list is the core feature of one of the world’s most popular treaties (by participation), the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (World Heritage Convention). The treaty celebrates and provides a protective framework for listed sites of “outstanding universal value,” and the World Heritage List today includes 1223 heritage sites in 168 countries. The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks became only the fourteenth cultural or mixed cultural-natural heritage site in the United States to make the list.

The litigation’s friction points nonetheless highlight lingering questions at the intersection of the Takings doctrine and international cultural heritage law. First, the case brought into question when holders of private property rights ostensibly must be ousted to satisfy the treaty’s requirements of “authenticity” and “integrity.” Second, the litigation embodied a resurgent, palpable resistance to recognizing public parks and other aesthetic objectives as a valid “public use” under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause and its state corollaries. In doing so, it offered another data point on “public use” in the post-Kelo environment.

The Octagon Earthworks Site & the Takings Controversy

According to the nomination file submitted by the United States, the Octagon Earthworks and the larger Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks complex consist of massive, geometrically shaped mounds constructed by the Hopewell culture that flourished in the Ohio River Valley as a religious movement (rather than a distinct indigenous group) from approximately 1CE to 400CE. The United States observed that the Octagon Earthworks showcase the vanished culture’s profound mathematical skill and astronomical understanding because corners of the octagonal shape “encod[e] all eight lunar standstills over an 18.6-year [lunar] cycle.” When the moon peaks at its northernmost point at the end of each lunar cycle, it “hovers within one-half of a degree of the octagon’s exact center,” making the site “a testament to indigenous sophistication.” The mounds were long known to form part of an ancient ceremonial site, but modern scholars only came to recognize them as a mathematical and cosmological marvel in the 1970s.

Ohio’s state historical organization initiated a condemnation proceeding in 2018 to take full possessory rights through eminent domain. In a twist from the usual takings action, the organization already owned the property in fee simple since 1933. But it did not possess the full idiomatic “bundle of sticks” because it had continuously leased it to the challenging party, the Moundbuilders Country Club. The litigation established that the club had operated a golf course on the mounds since 1910, initially pursuant to a lease with the city, the organization’s predecessor-in-interest. In fact, the nomination file acknowledges that the private country club was established for the express purpose of operating a golf course on the site as a cultural preservation measure. The city at the time lacked funds to create a public park to curb encroaching development and considered a golf course a viable alternative. In 1997, the historical organization renewed the club’s lease until 2078.

The club first challenged the basis for condemnation of its leasehold. Like most states in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. City of New London (2005), Ohio firmed up takings requirements under its state constitution, both through legislation and case law that judicially ratcheted down the deference owed to legislative determinations prescribing the government’s eminent domain powers. The challenge reached the state’s highest court, which ruled in State ex rel. Ohio History Connection v. Moundbuilders Country Club Co. (2022) that the historical organization could acquire full possessory rights to the “extraordinary piece of land.” The court observed that “[t]he historical, archaeological, and astronomical significance of the Octagon Earthworks is arguably equivalent to Stonehenge or Machu Picchu.” The ruling left the parties to tussle only over the measure of just compensation, which they resolved in the recent confidential settlement.

While the litigation was pending, the larger complex comprising the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks was added to the World Heritage List. Under the treaty, immovable cultural property qualifies if it possesses “outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science” or “outstanding universal value from the historical, aesthetic, ethnological or anthropological point of view.” In addition to the primary criterion of “outstanding universal value,” cultural sites must also meet one of ten additional criteria. The Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks qualified with two: representing “a masterpiece of human creative genius” and bearing “a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared.”

Private Custodians and Public Assurances of “Authenticity” and “Integrity”

According to the Ohio Supreme Court, the club asserted that it could maintain its leasehold at the Octagon Earthworks site, notwithstanding the site’s (prospective and then eventual) World Heritage status. It stressed that its leases obligated it “to preserve and maintain” the site and that it provided reasonable public access. The historical organization answered that it “could not convert the private golf course into a public park” without extinguishing the leasehold.

By all accounts, the club mostly acted as a good steward during its century-plus use, and its status as a private party was not automatically disqualifying. The World Heritage Convention does not require government control over nominated or listed properties. For example, the privately owned Guggenheim Museum comprises part of the World Heritage site celebrating the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, and several private properties are proposed for the nomination of Civil Rights Movement sites.

But the club also operated an active golf course on the site, installed paths for golf carts, and disturbed the mounds when renovating. Tensions over public access increased over time. Several mounds were off-limits to public use for much of the year, and the country club also imposed onerous restrictions that curbed use of the central part of the site. For example, the club assessed an access fee of almost $25,000 for a planned “moonrise celebration” at the site, to cover the costs of additional insurance, security, and a temporary platform to keep the public off the green. In arguing that it could coexist with the public on the site—and even making that argument the keystone of its motion for reconsideration—the club confused the ability of private property owners to maintain World Heritage sites with feasibility.

Not only was coexistence between golfers and the public infeasible, but swinging clubs, roving golf carts, and paved pathways were foreclosed by the treaty’s authenticity and integrity requirements. A nominating country must pledge to ensure the site’s authenticity and integrity, and failure to do so can lead to delisting, a draconian measure that the multinational World Heritage Committee has implemented for Liverpool and Dresden and threatened for Vienna. The treaty’s Operational Guidelines make clear that authenticity means that a site’s cultural values are expressed in attributes that include form and design, use and function, and location and setting. Integrity, on the other hand, “is a measure of the wholeness and intactness” of the site, which considers whether it suffers from development or neglect.

To this end, federal regulations provide that privately owned or controlled properties must have documented protective measures, such as real covenants that prohibit, “in perpetuity, any use that is not consistent with, or which threatens or damages the property’s universally significant values[.]” The regulations also provide that “no non-Federal property may be nominated to the World Heritage List unless its owner concurs in writing to such nomination.” New federal regulations on World Heritage nominations were proposed in December 2024 to help close gaps, including by shoring up the definition of an “owner” whose concurrence is required. The proposed regulations would limit the definition to holders in fee simple—unlike the definition of “owner” under Ohio’s eminent domain statutes, which extends to any individual or entity “having any estate, title, or interest in any real property sought to be appropriated.”

Aesthetic Takings

The club’s strenuous assertion that the taking was not “necessary” for a valid “public use” is more perplexing, even though the site’s World Heritage status was aspirational at the time of the taking and only materialized during the litigation. A government’s ability to take property through eminent domain for public parks is well-trod law, and Ohio law expressly specifies that public parks “are presumed to be public uses.” But the state’s post-Kelo legislative changes added the necessity requirement as a preamble to more specific requirements about taking blighted areas for redevelopment. The elevation of state takings standards above the federal minimum standard decoupled a long history of shared interpretation. The result may ultimately give less force to longstanding precedent for aesthetic takings for cultural heritage sites.

As far back as the late 19th century, the U.S. Supreme Court made clear that takings could be used for public parks. The Court in United States v. Gettysburg Electric Railway Co. (1896), for example, extolled the virtues of eminent domain to acquire private property rights to form a historically and culturally significant site: the Gettysburg National Military Park.

In 1929, on similar facts to those here, the Court even awarded penalties for a “frivolous” appeal because the appellant had “no basis for doubting the power of the State to condemn places of unusual historical interest for the use and benefit of the public.” The case concerned the Shawnee Mission, a site of “unusual historical interest” for which the state historical society acted as custodian. The City Beautiful movement of this same era often relied on takings to replace tenements and other downtrodden urban areas with public parks and scenic areas. Such initiatives sometimes had a sinister side when they disproportionately impacted minority communities, as when an African-American neighborhood in Charlottesville was replaced with a public park containing a monument to Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. (The Jackson monument and the infamous statue to General Robert E. Lee nearby were both donated by a city benefactor in the 1920s and removed in 2021.)

Here, the club suggested that it established a higher “public use” than a less-profitable heritage site. As the Ohio Supreme Court observed, the club argued “that its positive economic impact in the community and its efforts to preserve the earthworks provided a far greater tangible benefit to the public than the hypothetical and unlikely benefit to the public that allegedly would be realized by the appropriation [if listed on the World Heritage List].” Curiously, this argument is the antithesis of the anti-Kelo resistance, which objects to Kelo’s deferential gloss on “public use” based on increased tax revenue and economic development. Indeed, counsel for the Kelo homeowners raised the opposite hypothetical in their oral argument, arguing that it would subject a church to a valid taking when it “would produce more tax revenue and jobs if it were a Costco, a shopping mall or a private office building.”

To be clear, courts so far seem poised to reject such arguments, as the state courts did here. A similar takings dispute was also settled in 2023 for a visitor center and museum near The Alamo in San Antonio, part of another World Heritage site. Congress, too, has annotated the Takings Clause by acknowledging that use of eminent domain “to establish public parks, to preserve places of historic interest, and to promote beautification has substantial precedent.” Last year, the Second Circuit upheld a city’s exercise of eminent domain even for a “passive use park,” an unimproved tract acquired to prevent the construction of a so-called “big-box” store. The lawsuit, in which the challengers were represented by the same legal counsel as the challenging litigants in Kelo, may be destined for the U.S. Supreme Court.

Even if heightened state standards for takings start to chip away at parks more generally, a World Heritage site’s recognized “outstanding universal value” should affirm a government’s right to flex its eminent domain power. As the court said about the Octagon Earthworks, “This is not just any green space. It is a prehistoric monument that has no parallel in the world in its ‘combination of scale, geometric accuracy, and precision.’” Now the public can visit a cultural heritage site that joins the impressive company of the best-known World Heritage cultural sites worldwide, including the Great Wall, Machu Picchu, the Taj Mahal, Vatican City, Rapa Nui, and Stonehenge.

*Anne-Marie Carstens, JD, DPhil, is Associate Professor of Law at the University of Baltimore School of Law and Senior Fellow at the Center for International and Comparative Law (CICL). She has written extensively in the fields of public international law, property law, and cultural heritage law, including as co-editor of a book and author of several book chapters and articles.

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Daniel Ricardo Quiroga-Villamarín*

In the collective imagination of international lawyers and scholars of international affairs alike, perhaps the most vivid image we have of Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” might be of its absence. While a tapestry reproduction of this famous artwork has adorned the entrance to the Chamber of the United Nations Security Council since September 13 1985, it was briefly “covered up” in February 2003. The reason was that Colin L. Powell, then Secretary of State of the U.S., delivered an infamous speech before the United Nations Security Council on Iraq’s failure to disarm —leading, eventually, to the so-called Second Gulf War later the same year. Instead, a blue curtain with the emblem of the United Nations was conspicuously hung. And, from a specific angle, TV cameras were able to capture a dismembered “horse’s hindquarters […] just above the face of the speaker.” While there is no public record of the decision-making behind this aesthetical choice, journalists have long speculated that it “would be too harrowing, too politically pointed if Colin Powell were to be shown defending war in front of this great denunciation of war” (see also here). Be that as it may, this minor incident bears witness to the entanglements of art, war, and law in our unending quest to create a just international order.

This quest, of course, began long before the establishment of the United Nations in 1945 —and even perhaps of its immediate predecessor institution, the League of Nations (thereafter, the League), in the wake of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20. With this in mind, in this short intervention, I trace the connections between the Spanish Civil War of 1936 (the conflict which originally inspired Picasso’s work) and the League, all the way to the current challenges our liberal rules-based international order (with the United Nations as its cornerstone) is facing, using the many lives of the “Guernica” as a running thread. For the horrors that once inspired Picasso’s century continue to haunt our times —in fact, they seem to be returning with a vengeance on the world stage.

The entrance to the Chamber of the League’s Council (which, in many ways, worked as the inspiration of our contemporary Security Council) also has a connection with the Spanish polity. As I’ve explained with more detail elsewhere, all its interior décor had been donated by the Second Spanish Republic in the mid-1930s. This included the Latin-inscribed heavy bronze doors that guarded the entrance to the League. But the centerpiece of the Spanish donation had been the mural “The Lesson of Salamanca,” painted by the Spanish —or Catalan, depending on who you ask!— artist José María Sert y Badia between 1934 and 1936. This image was affixed to the Chamber’s abode, and it towered over the delegates who sat in its semicircular table. To accompany it, Sert also created a series of smaller murals for the walls entitled “Hope and Justice,” “Social Progress and the Law,” “The Vanquished and the Victors,” and “Peace Revived and Peace Dead.” The result was what in German is known as a Gesamtkunstwerk: a “total work of art”: an overarching aesthetical structure that gave the Council’s Chamber a coherent identity. It was Sert’s, and Spain’s, homage to world peace. And yet, by the time it was actually installed in the League’s Palais des Nations (“Palace of Nations”) building in Geneva, Switzerland, it had become a symbol of war —and, eventually, of the League’s own demise.

In July 1936, a military uprising brought the crisis-ridden Second Republic to the brink of catastrophe —taking, along with it, the “Great Experiment” that was the early League of Nations. To the embarrassment of League Officials, after a period of indecision, Sert decided to pledge his allegiance to the Nationalist camp in the civil war. This meant that, by the time the Council met for the first time in its new Chamber on 2 October 1936, the painter of their most hallowed hall had open Fascist sympathies. It was in this very Chamber where the Republican Government made its case, unsuccessfully, for international assistance. That same month, the Italian Fascists invaded Ethiopia, a fellow member of the League and nominally equal state. By 1937, winds of war were once sweeping the European continent —eventually leading to the collapse of the international order centered on the League and the eruption of what we now call World War II. The League’s embarrassment over having Fascist artwork in the middle of a great war against it was shared also by the Rockefeller family. The lobby of their “flagship 30 Rockefeller” Plaza building also harbored Sert’s massive mural “American Progress.” The fact that this occurred only after they had sacked the original artist, the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, because he had included a prominent image of Lenin in his mural “Man at the Crossroads” is almost a joke that tells itself.

The aesthetical anti-Fascist war effort found an unlikely ally in Sert’s nephew: the Catalan (or Spanish, once again) architect, Josep Lluís Sert I López (see, generally, here). While the younger Sert had long admired the work of his uncle, he had thrown his weight behind the Republican cause. If the Spanish Civil War was a feud between brothers, as all civil wars are, then now the time had come for the two Serts to face their own family quarrel in the battle for the soul of modern Spanish art. They did so in the context of the Paris World Exposition of 1937, which had as its motto “Art and Technology in Modern Life.” Despite the ravages of the civil war, the legitimate government of Spain considered that it was “indispensable” to participate to garner international support in favor of the Republican cause. Their pavilion was designed by the younger Sert (along with Joan Miró and Alexander Calder) and it was crowned by Picasso’s “Guernica.” It was here where the painting first gathered international attention not only as an abstract condemnation of war but as a cri du cœur related to a very concrete ongoing conflagration. The exhibition-goers first saw it perhaps “did not understand that democracy on the whole continent was at stake.” It was not only a condemnation of an ongoing conflict, but a warning of a global war that already loomed on the horizon.

Given that the Fascist uprising had not —yet— won the civil war, they could not claim a place in the Expo’s Pavilions of Nations. But they found a willing sponsor in the Vatican City, a state that allowed its pavilion to act as a proxy for “Nationalist Spain.” The older Sert adorned this hall with a new painting called “the Intercession of Saint Teresa of Jesus in the Spanish Civil War” —as if there were any lingering doubts as to whether his true loyalties lied. While he collaborated with the Republican authorities to evacuate the “cultural treasures of Spain” and protect them from the ravages of the war, he did so because he was more concerned about left-wing iconoclasm than Fascist purges (see further here). His newest paintings deployed the characteristically style (use of massive figures and different shadows of gold) that he once used in the Rockefeller Center in New York City and in the League’s Council in Geneva, but now to wage the Spanish Civil War by other means. By 1939, the Republic was on the verge of military defeat as this conflict escalated into a wider global war. And Picasso’s “Guernica,” like many of Spain’s other human and more-than-human cultural treasures, found itself in exile. In particular, this painting was loaned by the artist by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City until “democratic freedoms” were reestablished in Spain. After the death of the former dictator in 1975, the original “Guernica” finally returned to Madrid in 1981.

This allowed, perhaps, the younger Sert to have the last word in this unfinished argument with his uncle. In 1955, Nelson A. Rockefeller commissioned a tapestry replica of Picasso’s work which he and his family would loan to the United Nations in 1985. Ever since (ignoring minor cover-ups like the one that occurred during Powell’s speech and a period of cleaning and preservation in 2021-2022), this central part of the younger’s Sert homage to the Republic has guarded the entrance to the United Nations Security Council —the most important organ of a new international order created in 1945 in a decisively “American way.” This is only fitting, considering that the younger Sert followed the “Guernica” into exile and had a prolific career in the U.S. —serving as Dean of Harvard Graduate School of Design between 1953-69 and becoming one of the most important figures in modernist architecture and urban planning. In exile, he and many other former Spanish Republican luminaries found a way to carry on with their lives despite all that was lost on the battlefield.

For that reason, it is not surprising that “Guernica” itself went onwards to live many other lives beyond those lost when a coalition of Fascists planes bombed the Basque country in April 1937. It has become a symbol of peace —and an indictment of the horrors of war— with echoes that go far beyond its Spanish (or Basque) origins. Indeed, in the painfully contemporary wars raging in Eastern Europe and Western Asia, the motif of the “Guernica” has been purposefully mobilized by victims to once again garner the world’s attention (see, for instance, here in relation to Ukraine, here with regard to Israel, and here in respect of Gaza). Its gaze still haunts international lawyers and foreign affairs experts when they pour into the United Nations Security Council Chamber to debate and deliberate about international law’s role in times of war and peace. In this intervention, I have tried to hold the painting’s gaze, looking deep in the abyss of its history. For its original meaning, and its many subsequent lives, offers a cautionary lesson about the entanglement of art, law, and war. We can only hope that those within the United Nations today do not forget that —in fact— the events that inspired the “Guernica” proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back for the League of Nations. Let us work together so that its contemporary resonances do not prove to be the death knell of our liberal international order.

*Daniel Ricardo Quiroga-Villamarín, Scholar in Residence, Decolonial Futures Research Priority Area — University of Amsterdam.

Contact emails: daniel.quiroga@graduateinstitute.ch & d.r.quirogavillamarin@uva.nl

ORCID: 0000-0003-4294-4379

Cover image credit

Feb 21, 2025 | HALO x ILJ Collaboration, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a collaboration between the Harvard Art Law Organization and the Harvard International Law Journal.

Yelena Ambartsumian* and Maria T. Cannon**

The Terms of Service of many generative artificial intelligence (“generative AI”) tools, particularly those that produce illustrations and images, require that the user grant the AI tool an “irrevocable copyright license” to both the inputs and the outputs. While the content that the user provides to the generative AI tool (the input), and the data sets on which the generative AI tool was trained (training data) may consist of copyrighted material, the same is not true for the output—for example, the image that the generative AI tool generates in response to a user’s prompt. For such content to be copyrightable, most jurisdictions, including the United States, require some level of human creativity or originality in the selection and/or modification of the AI-generated content. That means AI-generated work, alone—in response to a human user’s prompt—is not afforded copyright protection.

In its 2023 Rule on Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, the U.S. Copyright Office stated copyright protects “only material that is the product of human creativity.” In late January 2025, the U.S. Copyright Office published its highly anticipated report on the copyrightability of works created using generative AI. Far from signaling a departure, however, the Copyright Office maintains that there is no need for changes to legislation and that existing law can resolve questions of copyrightability and AI. While determinations are made on a case–by–case basis, the Copyright Office clarified that most prompt-engineering will not suffice: this is because, for copyrightability, a human must determine the elements of creative expression, and, currently, “AI systems are unpredictable” given that the same prompt can create various outputs.

The U.S. approach is similar to that of many but not all other jurisdictions. We provide below a comparative analysis on the copyright laws of the United States, EU, UK, China, and Japan. In short, while all jurisdictions require some level of human involvement, one seeking to copyright AI-generated work would have the highest chances of success in China or Japan. When comparing different approaches to copyright protection, it is important to remember that the rights and ownership of copyright matter most when there is an alleged infringement. This practical concern—coupled with the United States’ policy interest in maintaining a monopoly on producing and exporting creative and entertainment goods—means it soon may be time to reevaluate U.S. copyright law’s human authorship requirement, particularly as AI technologies rapidly develop.

United States

While the Copyright Office has granted registration to hundreds of works that incorporated AI outputs, where the applicant properly disclaimed the AI-generated content, it is not possible to copyright a work generated solely by AI today. As the Copyright Office recently explained, “prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control to make users of an AI system the authors of the output.” Copyright does not protect ideas but rather the creative expression of those ideas. Accordingly, as the Copyright Office reasoned, “prompts alone do not provide sufficient human control to make users of an AI system the authors of the output.” For copyrightability, some level of originality is a prerequisite, though the “level of creativity is extremely low,” and not to be confused with “sweat of the brow” or industrious collection. See Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991).

The hurdle to copyrightability stems from the “authorship” requirement in U.S. copyright law, found in the Constitution and the Copyright Act, and as interpreted by the courts. The Constitution gives Congress the power to promote the useful arts, by giving “authors” the exclusive right to their “writings” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 8). The Copyright Act, first enacted in 1790, thus protects “original works of authorship” (17 U.S.C. § 102(a)). The Copyright Office views this authorship requirement as “[m]ost fundamentally . . . exclud[ing] non-humans.”

But AI is not the first technology that has required us to re-think authorship and human involvement. While lower court cases over a century ago often sought to limit that which was protected, two early and important Supreme Court cases evidenced an expansive approach. See Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884) (Miller, J.) (holding photograph of Oscar Wilde a “writing” and photographer an “author”); Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., 188 U.S. 239 (1903) (Holmes, J.; Harlan, McKenna, J., dissenting) (holding posters advertising a circus are copyrightable).

In Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co., the Supreme Court reasoned that while some photographs result from purely mechanical actions and thus lack authorship, other photographs are the product of an author’s “intellectual conceptions” and design. The Copyright Office has since relied on Burrow-Giles and subsequent case law to imbue humanity into the authorship requirement for copyright registration. In its 1965 Annual Report, the Copyright Office explained “[t]he crucial question appears to be whether the ‘work’ is basically one of human authorship, with the computer merely being an assisting instrument, or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work (literary, artistic, or musical expression or elements of selection, arrangement, etc.) were actually conceived and executed not by man but by a machine.”

Accordingly, an artist that inserts a prompt into a generative AI model and receives a written, visual, or musical output in response is unlikely to have created a work capable of copyright protection. The Copyright Office would view this work as lacking “any creative contribution from a human actor.” (Although, in the United States, copyright is automatically secured upon creation of the work, registration is a prerequisite to filing suit.) But an artist that produces a work containing AI-generated material, which also required human involvement (by editing or modifying the output, combining the AI-generated elements with other elements, etc.) may have created an original work of authorship. Importantly, while the overall work may be protected (for example, a comic book, with its text and arrangement of elements), the individual AI-generated images within that work likely would not be, for now.

European Union

While no EU-wide unitary copyright exists, works receive protection according to the laws of the respective EU Member State. Currently, there is no prohibition on registering works made using AI as a tool (AI-assisted works). In fact, the recent EU AI Act does not directly address the question of registration of AI-assisted works.

On the subject of copyrightability of AI-generated works, there is little case law, apart from Infopaq International A/S v. Danske Dagblades Forening (Case C-5/08), in which the Court of Justice of the European Union (“CJEU”) held that copyright protection will only be available for works that are “the expression of the intellectual creation of their author.” What does this mean for the outputs of generative AI? In Infopaq, the CJEU suggests EU Member States should figure it out themselves (“[I]t is for the national court to make this determination”). Because the CJEU did not provide an exact formula, the States have some flexibility in interpreting and applying the law within their respective national frameworks. In a December 2024 policy questionnaire, the general view of the Member States was that AI-generated content could be eligible for copyright protection “only if the human input in their creative process was significant” (emphasis in original).

United Kingdom

The UK’s copyright laws have been shaped by EU harmonization, due to the UK’s nearly fifty-year membership in the EU, until 2020. Therefore, although early U.S. copyright law is rooted in the Statute of Anne (8 Anne c. 19, 1710), we see several departures between the American and UK systems today.

Per Section 1(1)(a) of the UK’s Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (1988) (CDPA), a literary, dramatic, musical, or artistic work must be an “original” authorial work. This originality requirement is interpreted in accordance with the relevant EU case law, including Infopaq and subsequent decisions, which hold originality is the “author’s own intellectual creation” and requires the author to make choices that “stamp the work created with their personal touch.” CDPA Sec. 9(1) also recognizes a separate category of works called “entrepreneurial works,” which include films, sound recordings and broadcasts; these works do not require originality to qualify for copyright protection but the term for their protection is shorter.

All of this said, the CDPA explicitly speaks to computer-generated works. Section 9(3) provides that for “literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer-generated, the author shall be taken to be the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.” In 2021, after seeking public comment on whether computer-generated works should continue to be protected, the UK Intellectual Property Office elected to keep the law in place. Section 9(3) does not specify the originality required for computer-generated works. Future case law will hopefully resolve whether Section 9(3) simply designates the author—or owner—for such works that are entirely AI-generated and thus lack a traditional human author. (In that case, the person prompting the general-purpose AI tool simply would be the author.) Or, the courts may require the same originality as for other authorial works—“the author’s own intellectual creation”—which would be difficult to evaluate, particularly in the case of an entirely AI-generated work.

China

The Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China approaches authorship through the lens of ownership, not originality. Historically, China’s Copyright Law lacked an “originality” requirement, to avoid confusion with the patent law requirement of “novelty” and “inventive step.” In 2002, the Regulations for the Implementation of the Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China (amended 2013) introduced the concept of “originality” in Article 2 but with little guidance. Originality is interpreted through case law, with divergent interpretations by the courts but generally requiring that works be original, reflect intellectual achievement, and embody a concept of originality, among other factors—sometimes characterized as a “‘sweat of the brow’ plus” standard (effort and some creativity).

In Li v. Liu, (2023) Jing 0491 Min Chu No. 11279 (2023), the Beijing Internet Court unlocked the path for artists in China to obtain copyright protections for outputs of generative AI models. Critically, the Court relied on Article 3 of the Copyright Law to categorize an AI-generated image as a “wor[k] of fine art” and thus capable of copyright protection.

Li v. Liu involved a plaintiff who created a picture of a woman in springtime using an open source program called Stable Diffusion—a diffusion model which is trained on noising and denoising images, much like a human artist. The plaintiff exercised numerous choices in wording and phrasing when writing the prompt (including negative phrases, such as no “bad hands, text, error, missing fingers, extra digits”). He also adjusted the parameters to fine-tune the output. After the plaintiff posted the final image on social media, the defendant removed the watermark and published the same image in an article, on an alternate online platform, without obtaining permission or a license. The plaintiff sued for copyright infringement.

After determining that AI-generated images are fine art, the Beijing Internet Court focused on examining the work’s originality. It analyzed factors such as the specificity of the prompts, the actual descriptions of elements of the finished image that could be generated, and the unique formula and method the plaintiff applied to obtain the final result. Here, the plaintiff demonstrated a trial–and–error creative process well known to all artists. The Court found that the cumulative impact of the plaintiff’s choices caused the contributions to meet the threshold of “original,” as applied to creative works.

In the end, the Beijing Internet Court ruled in favor of the plaintiff and his AI-generated work, but with the following caveat: AI-generated works will only meet the qualifications for copyright registration in “appropriate” (read: not all) cases, and whether or not a work meets this threshold will be determined case–by–case. Despite the guardrails, this decision gives artists greater freedom to use generative AI to create copyrightable works in China than in the United States (and perhaps even in the EU and UK).

Japan

Japan amended its Copyright Act in 2018 in response to the development of new technologies. Notably, Article 30-4 of the Act gives broad rights to use copyrighted material for information analysis, including to train AI models for commercial use—so long as the use of the copyrighted works does not unreasonably prejudice the interests of the copyright owner. In May 2024, the Copyright Subdivision of the Cultural Council published guidelines on AI and copyright. The Copyright Subdivision noted that copyrightability of AI-generated material rests on whether the human author has provided “creative contributions that surpass mere effort.” Examples include the amount and specificity of the instructions or inputs, the number of generation attempts, and the selection from multiple output materials.

Conclusion

Regardless of the jurisdiction, most courts seem to grapple with the human’s role in the AI-generated output, rejecting that a simple prompt is enough to constitute authorship or originality. We may need to rethink human authorship, as the AI Revolution changes the paradigm of how humans can express their creativity. By encoding neural network patterns and decision-making processes in such a way that closely mimics human thought, AI-powered technology can create new categories of creative goods—which, as we saw in Li v. Liu, also require protection against theft, copying, and unfair competition (just as the photograph in Burrow-Giles and the circus poster in Bleistein).

Apart from numerous examples of technology assisting artists in creating new possibilities of creative expression and copyrightable works (e.g., the camera, Photoshop, or Adobe Illustrator), there is another precedent for expanding our notion of authorship: conceptual art. As in the dispute between Maurizio Cattelan and Daniel Druet—the wax sculptor and artist who painstakingly executed some of Cattelan’s most famous works—we accept that Cattelan is the author, based on his instructions (the prompt) to Druet. Similarly, putting aside the U.S. doctrine of “works made for hire,” we also accept that Jeff Koons is the artist, and not his dozens of studio assistants—many of whom are sophisticated designers and engineers (and some of which are robots). Today’s copyright law is able to ignore that the studio assistant inevitably leaves her touch, even when following the artist’s instructions (or prompt). Why is AI treated differently?

Ultimately, the copyrightability of AI-generated outputs will rest not on the law catching up to current events but on the technologies’ further development necessitating change. Advances in prompt engineering (i.e., adaptive prompting, human-in-the-loop) will inevitably allow humans to have more control over the creative expression produced by the AI tool. Soon enough, we will be prompted to rethink the human’s participation in creative expression and whether (and how) we want to incentivize and protect such creation.

*Yelena Ambartsumian is the Founder of AMBART LAW, a New York City law firm offering outside general counsel services to startups, with a focus on data privacy, AI counseling, and intellectual property. Prior to founding AMBART LAW, Yelena founded the art-tech startup Origen, a collection management and analytics platform for emerging contemporary art. Yelena is a certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP/US) by the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAAP), and a co-chair of IAPP’s New York KnowledgeNet chapter. She has also worked as General Counsel at an engineering consulting firm, a Senior Associate at a premier global law firm handling complex commercial litigation and regulatory investigations, and Of Counsel at an art and cultural heritage law boutique. Yelena is a frequent contributor to the leading arts magazine Hyperallergic, on topics including copyright and cultural heritage destruction.

**Maria T. Cannon is an Associate at AMBART LAW and is a certified Artificial Intelligence Governance Professional (AIGP) by the International Association of Privacy Professionals. Maria frequently writes on the intersection of art, law, and technology and has been published by the American Bar Association, and the New York State Bar Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section (EASL), among others. She is an attorney admitted in New York State, and prior to her work as an associate in AI counseling and data privacy, she worked as a student extern in the Legislative Drafting Division of the North Carolina General Assembly.

Cover image credit

Dec 20, 2024 | Online Scholarship, Parella Symposium, Perspectives

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a four-piece symposium that examines Kishanthi Parella’s work, “Enforcing International Law Against Corporations: A Stakeholder Management Approach,” featured in Volume 65(2) of the HILJ Print Journal.

*Monika U. Ehrman

I. Introduction

Corporate secrecy is not a new phenomenon. Companies routinely take steps to ensure that prized information is secured and kept from competitors. Securing intellectual property as trade secrets keeps the information confidential for as long as the owner employs reasonable measures to guard the information—unlike patents, which offer term protection of certain types of intellectual property in exchange for public registry. Geographical and geological location data are especially lucrative for mining and petroleum companies, which target mineral resources for extraction and production. So, it is not unexpected that space mining companies would want to do the same. But should they be able to do the same is another question.

In December 2023, AstroForge, a private company, announced a proposed launch to surveil an asteroid for commercial mining. Formed from the remains of planetary and other debris following the creation of the solar system over 4.5 billion years ago, asteroids are small outer space objects that orbit the Sun. Not only do they contain insightful information about the birth of our planet and the possible origins of life, but they may also be financially valuable. Some asteroids contain high ore content of minerals that are rare or critical to modern technologies. So, it is not surprising that AstroForge wants to mine an asteroid. Which one? We do not know—the company does not want its competitors to find out.

Why should it matter that AstroForge will not disclose its intended extractive target? Because its target is in outer space—the province of all humankind. As such, does everyone on Earth own what AstroForge and extraction companies like it mine? That part is not clear to everyone. However, what is more clear is that any disputes over these asteroids or other outer space bodies are governed by international law, including such landmark treaties as the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Agreement. And international law governance prevails where state actors carry out various duties in the international forum. In the case of space, almost all major actions are performed by governmental entities. But that is about to change.

Private entities, such as AstroForge, represent a new brand of space explorer—they are private sovereigns. They hold loyalty not to the nation, but to the investors. And therein lies the challenge with international law as the primary mechanism to govern private sovereign behaviors. Professor Kishanthi Parella explains, “Many corporate actors do not abide by international law because the international legal order lacks adequate mechanisms to ensure their compliance.” So how can one control the behavior of extraction companies in outer space? In her innovative Harvard ILJ article, Enforcing International Law Against Corporations: A Stakeholder Management Approach, Parella proposes we apply principles of corporate stakeholder governance to international law, by using non-state actors as a mechanism to force good corporate behaviors. This innovative approach offers success in challenging hybrid environments such as outer space.

II. Current Authority to Govern Potential Space Mining Activities

Scholars generally analyze outer space governance under the existing rubric of international law, which mainly consists of the: (i) 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Outer Space Treaty”), (ii) 1968 Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Rescue Agreement”), (iii) 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (the “Liability Convention”), (iv) 1976 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Registration Convention”), (v) 1979 Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Moon Agreement”), and (vi) 2020 Artemis Accords.

While multilateral approaches were once favored as a traditional mechanism to govern outer space, individual state action is on the rise, largely in part because of increased identification of resource potential—namely, the availability of precious minerals. Creation of an international agency or granting the United Nations authority over outer space resources is highly unlikely; and the creation of individual state agencies, while more tenable, does not address the international, cooperative governance required for the global commons. The third option thus prevails as the most likely scenario—states assert that each has the unilateral authority to extract resources. As state actors continue to embrace this strategy, other state actors have little choice but to follow the same approach, decreasing the likelihood of multilateral agreements. Thus, Parella’s framework offers a realistic governance overlay, allowing for oversight and changemaking without the niceties of formal international law.

III. The Necessity for Layered Approaches to Governance

International lawyers often express confidence in the rigor of international law to govern activities in space, but there are high tensions over the acceptance of multilateralism in an era of trending isolationism, exceptionalism, and non-interventionist stances. The political fluctuations of these policies may provide reassurance that multilateralism and international cooperation survive and endure. However, in those multilateral lulls and lows, there is an increased risk of private companies or isolationist States establishing extraction customs in outer space. Once established and ensconced, it becomes difficult to reject those practices and law often evolves around them.

The other major challenge is the physical and temporal distance of outer space regions to the Earth. Outer space resources—hidden resources—are far beyond the sight of Earth-bound observers, a physical manifestation of the saying, “out of sight, out of mind.” Control of outer space resources may still be manageable due to the restricted number of available commercial launch facilities; however, States make independent decisions with respect to launches and the number of space launch sites will only increase. Although commercial launch capabilities are now restricted to a few global centers, the privatization of commercial space transport will no doubt continue as entry costs decrease.

While international law remains an important foundation to govern space mining activities, it should not be the sole mechanism and, indeed, cannot. During a meeting of the SMU Subsurface Resources Research Cluster on April 29, 2024, Dr. Guillermo Garcia Sanchez described the energy legal process as a system of interconnected phases which only partly consist of the laws and contracts that govern exploration, discovery, development, production, and reclamation. These legal processes also include public and private law, in addition to industry customs and practices and other norms. The substantive laws and contracts operate in conjunction with the law of the resource situs—the law of the jurisdiction in which the resource is located. For example, offshore petroleum deposits are generally located in State waters (either in the Continental shelf or Exclusive Economic Zone), where the law of the State applies. In much of the rest of the world, the State, as sovereign, owns all mineral resources. However, States may invite or open resource development to firms outside the State, which then introduces international law to the transaction via the relationship between State and non-State firm(s). But where the resource is located beyond State boundaries, such as the high seas or outer space, international law also applies where recognized by consenting States—like those who are parties to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Outer Space Treaty.

What happens then when space mining actors disregard the law, whether out of principle or for convenience? Yet, that firm belief in the absolute resolve of international law fails to consider the lessons of historical import. Space mining is just an old story in a new realm. During the Gold Rush of the late 1800s, immigrant miners from diverse lands, including England, Germany, Mexico, and South American nations, ventured to the American West to make their fortunes. Most all those ancestral miners came from countries where the sovereign owned all mineral resources and, critically, paid a royalty—the regalian right—to the State. The miners were not fond of such sovereign ownership and payment and had no intention of deliberately instituting the same in these new American mines. So, they borrowed those helpful traditions and customs of their native mining districts, such as free access and the extralateral right, while denying others, such as reporting production and provisioning a royalty. Subsequently, though the Western mineral deposits were primarily located on federal lands, the miners implemented their own desired customs, later codified by Congress into the General Mining Law of 1872—which still applies today.

Why then were these miners able to keep ownership of mines and the produced minerals? Arguably because of a governance vacuum. Though there were applicable laws on ownership of the land—“there was no law governing the transfer of rights to these minerals from public ownership to miners.” The miners took advantage of such regulatory absence.

IV. Governance Vacuums and the Parella Stakeholder Governance Model

Many believe the question of asteroid space mining to be settled—that States may not claim ownership of asteroids, but they can own what they extract. From a property perspective, I contest this distinction. I believe that the action of extraction of the part is by its nature an assertion of ownership of the whole. But while legal uncertainty increases the corporate firm’s transactional risk, it also increases the availability of first mover advantage and, arguably, the opportunity for innovation. High risk-high reward companies, like venture-capital backed space mining companies, may prefer operating in governance vacuums, where property right legal uncertainty abounds. Enter Parella’s stakeholder governance model. Parella’s model provides greater stability where a weak system of ownership exists and some stability where no framework exists.

The main benefit of applying Parella’s model to space mining ventures is that it applies to both public and private companies. A central challenge in space extraction companies is a lack of transparency due to their often-private nature. Five of the largest companies—AstroForge (U.S.), Karman+ (U.S.), TransAstra (U.S.), Origin Space (China), and Asteroid Mining Company (U.K.) are all privately-held companies backed by venture capital. Before it was acquired by blockchain company, ConsenSys, Planetary Resources was a U.S. privately-held company, whose backers included billionaires Ross Perot Jr., then Google Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and Chairman Eric Schmidt, and former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Co-Chairman John Whitehead. Neither corporation nor unincorporated publicly-traded company, these private companies have lesser built-in corporate accountability measures, like traditional shareholder governance. Further, there is not systematic financial reporting and mandatory disclosure of metrics like those on environmental, social, and governance goals; there may not be rigorous oversight for investors by federal agencies, such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Here is where Parella’s framework shines. Instead of relying on formal mechanisms to govern or shape company behavior, Parella looks to stakeholder management to pressure corporate actors to: “frequently align their behavior to conform to the values and expectations of a range of non-state actors—corporate stakeholders—such as consumers, employees, insurers, financial institutions, investors, industry organizations, and NGOs, among others.” She theorizes that “[t]hese stakeholders can address important gaps in the international legal order by offering incentives that nudge corporate actors toward compliance with international law.”

Moreover, Parella’s model is also practical, relying on enforcement by a variety of norm entrepreneurs and not just on a single State actor. Of particular interest to me is her meticulous, tabular identification of various stakeholder enforcement mechanisms, one of which is “monitoring.” Monitoring that is akin to an audit function will be crucial to space mining governance due the physical distance of potential mining sites from Earth observation—the main asteroid belt (between Mars and Jupiter) lies between 111.5 and 204.43 million miles from Earth. Because of the lack of physical visual site and a (cost-effective) method to visit the operation, the distant extraction community of miners, subcontractors, and other support tools/machines, can conduct operations without actual, observable oversight. Even the transmission of data to and from the mining site requires time, as a function of the distance. Although many missions and operations are conducted at great physical distances—for example, China’s recent unmanned mission to the far side of the Moon, the opportunity to disregard international law and custom or for malfeasance or misconduct increases without monitoring and the ability to audit.

Mining on planetary or lunar bodies is more complicated. As opposed to the Outer Space Treaty, there are fewer signatories to the Moon Agreement, and even fewer to the Artemis Accords. Notably, the major space exploring States, Russia and China, have signed neither. But whereas the potential for asteroid mining is great due to the millions of bodies surveyed, Martian and lunar mining sites are arguably more difficult—the property rights are more complicated. The difficulty arises with respect to the resource location. Minerals are not scattered among planetary crust in even fashion. They accumulate due to varying geologic and geomorphologic conditions and events over great periods of time. If one company establishes a mining location on Mars or the Moon, that location may preclude others from economically accessing the resource without disturbing the original company’s operations. Establishing, protecting, and defending mining operations could easily accelerate into risky, geopolitical situations. Parella’s model can diffuse future tensions by establishing cooperative frameworks, best practices in supply chain and operational management, and provide labeling of sourced minerals to help purchasers and end-users identify those minerals that are “conflict-free” or ESG compliant. The possibilities to apply Parella’s model are endless; and the potential to reduce threats is significant.

V. Conclusion

Natural resources are beset with antiquated legal doctrine. The lumbering laws governing mining arose from customs that primarily benefited the mining communities who formed them. Current congressional tensions hinder the passage of new natural resource legislation, though the Biden Administration has made good efforts to identify possible reforms to the 1872 General Mining Law. The incoming Trump Administration is likely to advance mining and space resource extraction, as it previously did during its first term. As always, science and technology has advanced far faster than the law and policy to govern them. And therein lies the power of Parella’s stakeholder management approach—it relies on an existing discipline that has had great success influencing corporate behaviors. International law is still the foundation of outer space activities. Applying stakeholder management principles, in addition to private contract and insurance, adds security to the business and mitigates the risk of failure.

Cover image credit

Dec 20, 2024 | Online Scholarship, Parella Symposium, Perspectives

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a four-piece symposium that examines Kishanthi Parella’s work, “Enforcing International Law Against Corporations: A Stakeholder Management Approach,” featured in Volume 65(2) of the HILJ Print Journal.

*Carla L. Reyes

Introduction

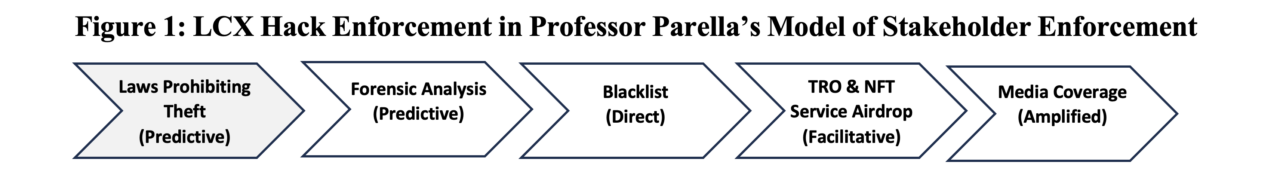

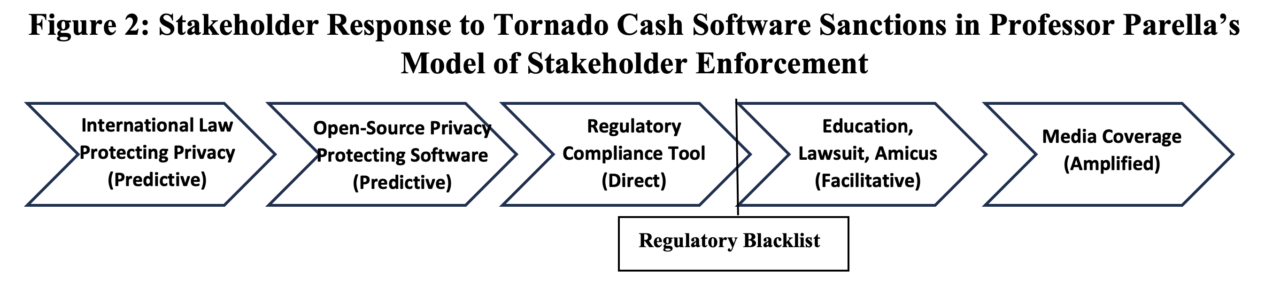

Recent attempts to enforce law in an era of decentralized digital activity have supplied some surprising results. For example, a regulator places open-source software on the list of sanctioned nationals. A settlement agreement requires the “destruction” of immutable digital assets. Digital art is targeted as unlawful offerings of investment contracts. Centralized entities that create front-end websites for decentralized exchange technology become targets of enforcement for activity they did not actually undertake. These represent just some of the many announcements of regulatory activity that permeate the news cycle, documenting attempts by governments around the world to enforce domestic and international law against actors operating through decentralized technology. Meanwhile, developers and other actors in the decentralized software community file lawsuits claiming government overreach and challenging the applicability of traditional enforcement mechanisms.

In particular, an ongoing debate exists as to the extent to which certain software constitutes an entity, and whether and to what extent existing law binds such entities. This debate offers a fertile arena in which to consider the applicability of Professor Kish Parella’s stakeholder management approach to enforcing international law against corporations in the context of alternative business governance models—namely, governance models adopted by decentralized business entities. Governments have entered an era in which many voice concerns about how to detect, prevent, and punish legal violations committed by entities operating entirely through decentralized computer code. Further, governments find themselves lacking credible tools—both in terms of the law and in terms of enforcement—to address these rising concerns systematically. If Professor Parella’s framework can be adapted to the era of decentralized entities, it might offer public law—both domestic and international—a clearer path toward legal and enforcement clarity. This short Essay considers this possibility in the context of decentralized business entities. In doing so, the Essay uncovers a surprising opportunity: stakeholder enforcement of international law in the decentralized era is more about questioning whether state legal enforcement itself upholds international law—seeking to claw back fundamental rights quietly lost to digital architecture as it developed over the last half-century.

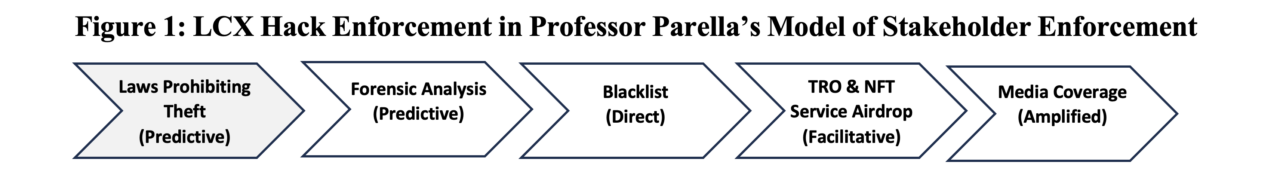

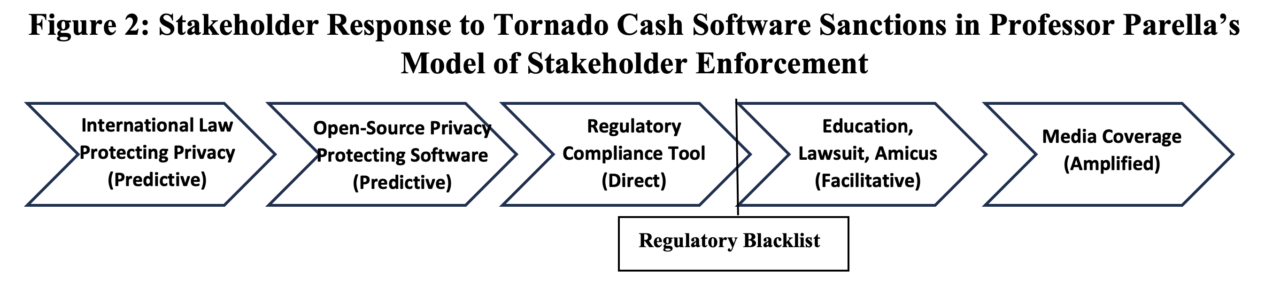

I. Decentralized Business Entities: Disrupting Your Average Corporation