Anna R. Welch and Sara P. Cressey*

With this new [asylum] program in place, we will be better equipped to carry out the spirit and intent of the Refugee Act of 1980 by applying the uniform standard of asylum eligibility, regardless of an applicant’s place of origin. We can thus implement the law based on a fair and consistent national policy and streamline what has sometimes been a long and redundant process.[1]

Gene McNary, Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, in remarks given weeks before opening of first asylum offices.

***

Amelia fled her home country in central Africa after the country’s repressive ruling regime singled her out based on her perceived political affiliations, subjected her to severe physical and sexual violence, murdered her sibling, and kidnapped and likely killed one of her children.[2] After arriving in the United States, she found an attorney who assisted her in preparing and submitting her affirmative asylum application along with extensive supporting documentation, including expert medical reports documenting the ongoing physical and psychological effects of her trauma. A year after submitting her application, Amelia had her asylum interview with a hostile asylum officer who spent several hours interrogating her as she recounted the harrowing persecution she had suffered. Another year of waiting passed before Amelia received a request for additional evidence and a notice that she would need to attend a second interview at the asylum office. Amelia complied with both notices but was nevertheless referred to immigration court, where she spent another five years awaiting a merits hearing. She was finally granted asylum by an immigration judge eight years after her original asylum application was filed.

Introduction

America’s promise of safe haven to those fleeing from persecution, an obligation enshrined in both international and domestic law,[3] too often remains unfulfilled, particularly for racial minorities and other marginalized groups. Indeed, the right to seek asylum at the southern border has been virtually nonexistent since Title 42 was implemented in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.[4] Meanwhile, those who do manage to make it into the United States to lodge an asylum claim face a Byzantine administrative process plagued by “monumental” backlogs, leading to years-long (or even decades-long) wait times.[5] This Article focuses on one particular aspect of the asylum system, reporting on the first ever comprehensive study into the inner workings of an asylum office in the United States.[6] The findings of the study, set forth in the full report “Lives in Limbo: How the Boston Asylum Office Fails Asylum Seekers,” reveal larger systemic failures within the broader affirmative asylum system.[7]

The investigation into the Boston Asylum Office, spearheaded by lead investigator Anna Welch, involved both qualitative and quantitative research methods. Researchers analyzed documents and data produced by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in response to litigation brought to compel compliance with a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, as well as USCIS Quarterly Stakeholder Reports. In addition, researchers conducted more than one hundred interviews with former supervisory asylum officers, former asylum officers, immigration attorneys, asylum seekers, and asylees. The research was completed in January 2022, and the report was released to the public on March 23, 2022. This Article reproduces the findings of the report, presented as a resource for practitioners, scholars, and policymakers. The report’s major conclusion is that the Boston Asylum Office maintains an asylum grant rate well below that of the national average.[8]

The Refugee Act of 1980 formalized the right to seek asylum in the United States, but “the law itself did little to define or prescribe the mechanics of obtaining this status.”[9] During the 1980s, the adjudication of affirmative asylum applications was governed by a set of interim regulations[10] under which immigration officers within Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) District Offices would adjudicate asylum claims.[11] During that period, criticism of the INS abounded as “unspecialized, under-paid, and over-worked” INS officers[12]struggled to apply the complex refugee definition.[13] On July 27, 1990, the INS issued a final rule establishing procedures to be used in determining asylum claims and mandating the creation of “a corps of professional Asylum Officers” who would receive specialized training in international law and conduct asylum interviews in a nonadversarial setting.[14] The INS then established – for the first time – seven asylum offices, with the goal of creating a fairer and uniform affirmative asylum process.[15]

Federal regulations still require that asylum officers receive “special training in international human rights law” and “nonadversarial interview techniques.”[16] USCIS training materials for asylum officers emphasize the importance of the nonadversarial interview:

It is not the role of the interviewer to oppose the principal interviewee’s request or application. Because the process is non-adversarial, it is inappropriate for you to interrogate or argue with any interviewee. You are a neutral decision- maker, not an advocate for either side. In this role you must effectively elicit information from the interviewee in a non- adversarial manner, to determine whether he or she qualifies for the benefit. . . . The non-adversarial nature of the interview allows the applicant to present a claim in an unrestricted manner, within the inherent constraints of an interview before a government official.[17]

Unfortunately, the affirmative asylum system remains plagued by many of the issues that the 1990 final rule was intended to solve. As discussed in detail below, the process for adjudicating affirmative asylum claims remains long and difficult and too often leads to inconsistent outcomes based on the applicant’s country of origin. The more informal, non-adjudicative framework for adjudicating asylum claims in the asylum offices lacks transparency and creates an opportunity for hostility and bias to permeate the decision-making process.

I. Summary of Major Findings

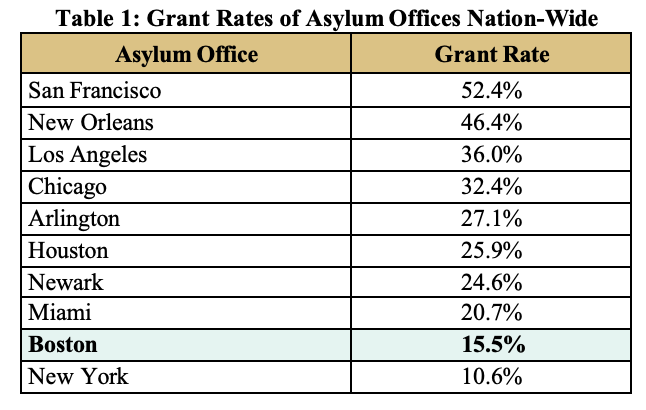

The Boston Asylum Office maintains an asylum grant rate well below that of the national average. Examining the average nationwide grant rate of asylum offices between 2015 and late 2020, we found that the Boston Asylum Office granted a little over 15 percent of its cases as compared to the national average grant rate of 28 percent. Examining monthly grant rates, we found that the Boston Asylum Office’s grant rates dropped into the single digits on multiple occasions. While the Boston Asylum Office maintains the second lowest grant rate in the country, several asylum offices around the country also maintain grant rates below that of the national average.

Indeed, many of the problems identified in this study are likely not isolated problems but rather are reflective of larger systemic failures pervasive in other asylum ffices around the country. As part of this study, we interviewed former asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers from asylum offices around the country. Many noted the prevalence of biased decision-making, the outsized role of upper management and/or supervisory asylum officers, and insufficient time to complete their job functions. Yet their functions are critical to ensuring U.S. compliance with international and domestic asylum protections.

We ultimately find that the Boston Asylum Office is failing asylum applicants in violation of international obligations and U.S. domestic law. The Boston Asylum Office’s biased and combative asylum interview process, asylum backlog, and years-long wait for adjudication has had devastating impacts on applicants and their families. If an asylum officer does not grant a case, the case is typically referred to immigration court, an intentionally adversarial setting.[18] Although the Boston Immigration Court has a significantly higher asylum grant rate than the Boston Asylum Office,[19] asylum applicants face even lengthier backlogs before being heard by an immigration judge, leading to further delay.[20] As a result, asylum seekers face years of legal limbo, rendering many individuals ineligible for social services and contributing to significant instability. The years-long wait to be granted asylum causes lengthy separation from family members (many of whom remain in life-threatening danger) and deterioration of the applicant’s mental health.[21]

Specific Findings:

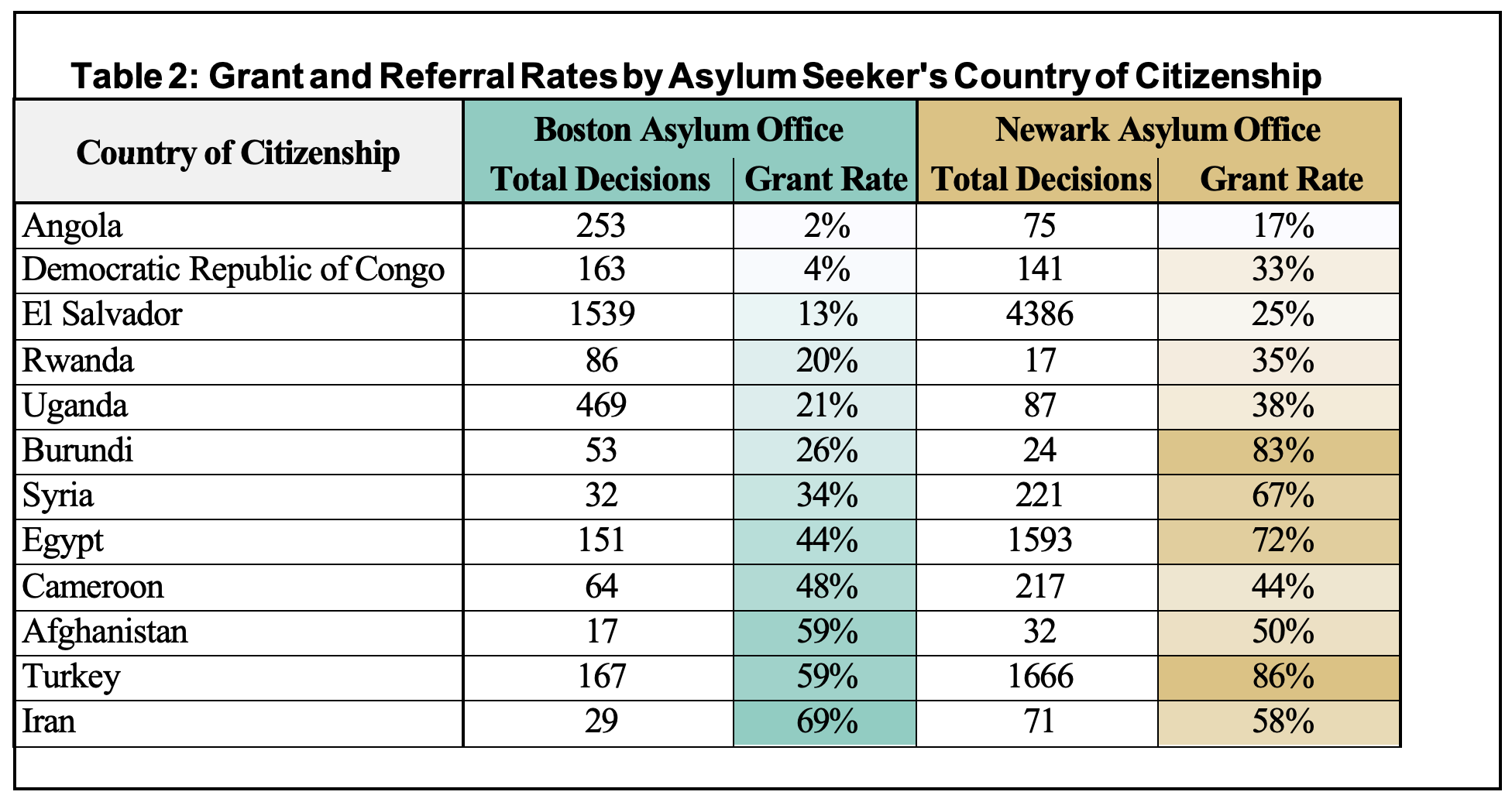

First, the Boston Asylum Office exhibits bias against applicants from certain countries as well as a bias against non-English speakers, as displayed in Table 2 below.

The Boston Asylum Office does not maintain a nationality-neutral determination process, as mandated by international and domestic law. Notably, applicants from certain countries – including Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, and Burundi – experience lower grant rates in the Boston Asylum Office than in the Newark Asylum Office.[22] From 2015 to 2020, the Boston Asylum Office granted asylum to just four percent of asylum applicants from the DRC despite extensive documentation of human rights abuses in the DRC. Indeed, the U.S. Department of State has acknowledged year after year that “significant human rights” abuses occur in the DRC, including that DRC security forces commit “unlawful and arbitrary killings . . . forced disappearances, [and] torture” against citizens.[23]

Interviews with asylum attorneys confirmed the prevalence of biased decision-making among adjudicators in the Boston Asylum Office. One asylum attorney noted, “the belief of the Boston Asylum Office is that [clients from certain African countries] are not telling the truth . . . We have taken a number of cases that have been referred from the Boston Asylum Office and then we have won them in court without a problem and there has been no suspicion about negative credibility.”[24]

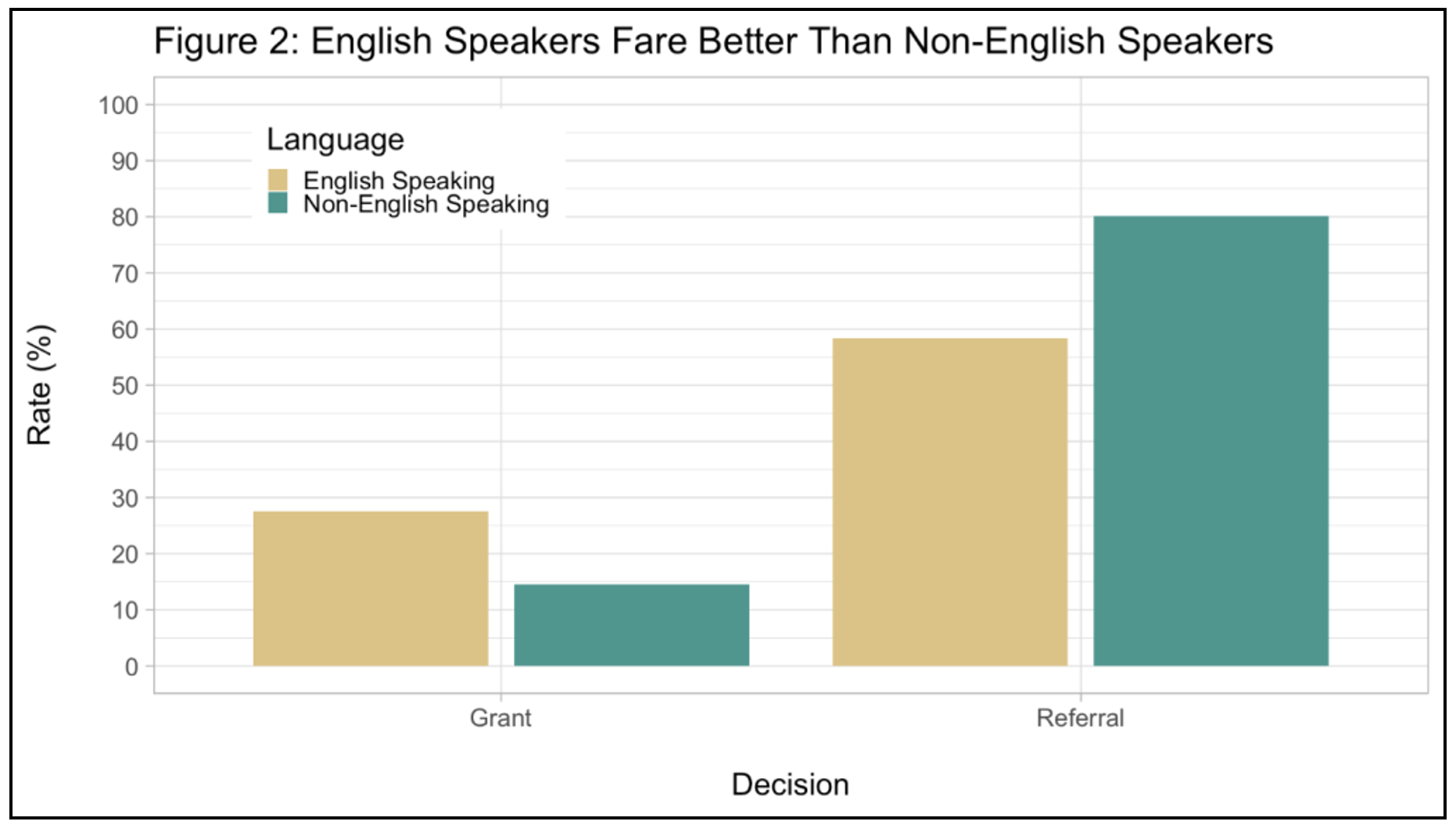

Moreover, data collected from our FOIA request revealed that English speakers are much more likely to be granted asylum in Boston than non-English speakers, even though speaking English is irrelevant to an individual’s eligibility for asylum.

As demonstrated in Figure 2 above, English-speaking asylum seekers are nearly twice as likely to be granted asylum as compared to non-English speakers. Conversely, non-English speakers are referred to immigration courts 80 percent of the time, while English speakers are referred to immigration court only 58 percent of the time.[25]

Second, the Boston Asylum Office’s low grant rate is likely driven by the oversized role for supervisory asylum officers. Although the Affirmative Asylum Procedures Manual requires that asylum officers be given “substantial deference” in deciding whether to grant a case,[26] we found that supervisory asylum officers exercise a high degree of influence over decisions made by asylum officers.

One supervisory asylum officer familiar with the Boston Asylum Office observed that the asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers hired in Boston generally trended against granting asylum.[27] Every decision rendered by an asylum officer must go through supervisory review. When a supervisory asylum officer returns an application to an asylum officer for further review or reconsideration, this creates additional work for the asylum officer. The officer may be forced to conduct additional investigation or even re-interview the asylum seeker to support their original decision. This additional work can lead to negative performance reviews because supervisory asylum officers can give asylum officers negative performance reviews if their decisions require reconsideration. Additionally, asylum officers are evaluated, in part, on the number of decisions they issue during a given timeframe. In light of these negative impacts, asylum officers are incentivized to write decisions their supervisor agrees with, regardless of whether they think a given applicant meets the requirements for asylum.

Third, asylum officers face time constraints and high caseloads that incentivize them to cut corners. By the end of 2021, the Boston Asylum Office’s backlog of asylum cases had grown to over 20,000 pending applications.[28] To ensure that asylum seekers fleeing persecution receive adequate due process, asylum officers are responsible for a lengthy list of job duties. These include conducting interviews with asylum applicants and engaging in a thorough review of an asylum applicant’s oral testimony and written documentation. Asylum officers must also remain abreast of ever-changing asylum laws and policies and country conditions. Several former asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers stated that they simply lacked the time to complete their required jobs. They reported feeling that they needed to rush through their review of asylum applications and decision drafting, even going as far as to recycle old decisions.[29]

Fourth, we found that compassion fatigue and burnout lead to lower grant rates. Former asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers observed that after time they became desensitized to the traumatic stories that accompany most asylum applications. One former asylum officer stated that asylum applicants’ traumatic stories became so “mundane as to lose salience.”[30] Troublingly, this skepticism is apparent to those appearing before the asylum officers. Asylum applicants and their attorneys noted that asylum officers were often dismissive of the asylum applicant’s trauma and were sometimes even combative with applicants. As discussed above, U.S. regulations require that asylum interviews be non-adversarial, meaning that an asylum officer must not argue with or interrogate an asylum applicant.[31] However, many asylum attorneys commented that asylum officers took an adversarial and combative approach with applicants, in direct violation of U.S. law.[32]

Finally, we found that asylum officers disproportionately focus on an asylum applicant’s credibility and small, peripheral details to find “inconsistencies” rather than the salient facts of an applicant’s case.[33] Their search for “inconsistencies” fails to recognize that many asylum seekers have experienced trauma and may suffer PTSD-induced memory loss. Moreover, given the massive asylum backlogs across the country,[34] it is very common for years to go by between the asylum applicant’s traumatic experience in their country and their asylum interview. Those years of waiting can lead to faded memories, particularly with respect to details about specific dates, times and smaller events.

II. Recommendations

We now turn to several recommendations to help address failures in U.S. compliance with international and domestic asylum protections.

First, the Boston Asylum Office must develop enhanced transparency and accountability. We call for a U.S. Government Accountability Office investigation into the Boston Asylum Office and recommend replacing asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers who demonstrate bias and/or a lack of cultural literacy. We also call for a system to mitigate the outsized role that supervisory asylum officers play in swaying the decisions of asylum officers.

Second, we recommend that all asylum interviews be recorded and that those recordings be made available to asylum applicants and their attorneys, where applicable. Currently, asylum interviews at all asylum offices around the country take place behind closed doors with no recordings or written transcripts. The only written record of what took place during an asylum interview is the asylum officer’s notes. Such notes are often not reflective of what happened during the interview, incomplete, riddled with errors. Absent an accurate recording or transcript, asylum officers may employ improper practices, such as adversarial, insensitive and biased interview techniques, with impunity. This is especially true if the asylum applicant does not have an attorney to bear witness to what occurred during the interview. Importantly, the creation and preservation of accurate records of asylum interviews is critical to ensuring that asylum seekers’ due process rights are realized in immigration court. The asylum officer’s notes and assessments are often used to impeach asylum applicants in immigration court even if they are not reflective of what was said during the interview.

Third, we call for more support and resources for asylum offices. We recommend limiting officers to one interview per day, instituting more rigorous hiring standards, support structures, and mentorship, and improving asylum officer training, with a focus on mitigating bias and racism. We also recommend developing more asylum officer trainings on trauma, compassion fatigue, and cultural literacy.

Fourth, we recommend a paper-based adjudications process that would take the place of the asylum interview when it is clear asylum should be granted based on the evidence submitted. This would help address the backlog and preserve resources by limiting asylum interviews to cases where the outcome is less certain, or where credibility or national security are relevant concerns.

Finally, we recommend ending the “last-in, first-out” (LIFO) policy that prioritizes the adjudication of cases most recently filed.[35] The LIFO policy extends wait times for hundreds of thousands of asylum applicants whose cases have already been pending for years.36

Conclusion

Since this study was released in March 2022, several members of Congress from Massachusetts and Maine called on the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General to investigate the Boston Asylum Office to hold the office accountable.37 To date, an investigation has not yet been granted, and the issues brought to light by this study remain pressing.

The Boston Asylum Office has instituted several changes that we hope will bring it into better compliance with its legal obligations. These changes include increasing the number of asylum officers and overhauling supervisory staff. The office has also added a “section chief” who is tasked with ensuring that asylum officers make legally correct decisions, rather than decisions that respond to pressures from supervisory asylum officers.

While these developments are certainly encouraging, the troubling fact remains that practices at the Boston Asylum Office have diverged significantly from the requirements of U.S. and international asylum protections. To ensure that asylum seekers in New England receive the protection to which they are entitled, monitoring data and practices of the Boston Asylum Office remains necessary. As it stands, stories like Amelia’s who, as mentioned at the outset, was forced to wait over eight years for her asylum case to be finally adjudicated are far too common, leading asylum seekers with meritorious claims to remain in limbo for years, unable to petition for family members who may still be living in danger.

Our sincere hope is that other advocates will use this first-of-its’s-kind case study as a model. Although the study focused on one asylum office, the issues we uncovered reveal larger systemic patterns likely pervasive throughout the United States affirmative asylum system. Given the life-or-death stakes in asylum cases, additional investigation remains imperative to ensure due process is realized for asylum seekers.

* * *

[*] Clinical Professor Anna Welch is the founding director of the University of Maine School of Law’s Refugee and Human Rights Clinic. Sara Cressey is the Staff Attorney for the Refugee and Human Rights Clinic. The authors express our sinceregratitude to the current and former Refugee and Human Rights Clinic student attorneys who devoted countless hours topreparing and writing the report entitled Lives in Limbo: How the Boston Asylum Office Fails Asylum Seekers, upon which thisArticle is based, including Emily Gorrivan (’22), Grady Hogan (’22), Camrin Rivera (’22), Jamie Nohr (’23), and Aisha Simon (’23). The report was also made possible by volunteers Adam Fisher and Alex Beach, who conducted valuable analysis of data collected from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Finally, the authors are indebted to the Clinic’s collaborators who co-authored the report: the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project (ILAP), American Civil Liberties Union ofMaine (ACLU of Maine), and Basileus Zeno, Ph.D. The report received the Clinical Legal Education Association’s 2022 Award for Excellence in a Public Interest Case or Project. An extended version of this piece is forthcoming in early 2024 in Volume 57, Issue 1 of the Loyola of L.A. Law Review.

[1] Gene McNary, INS Response to Immigration Reform, 14 IN DEFENSE OF THE ALIEN 3, 6 (1991).

[2] This story is drawn from the stories of multiple clients of the Refugee and Human Rights Clinic. Names and details have been changed to protect the privacy of those clients and preserve confidentiality.

[3] Congress enacted the Refugee Act of 1980 to bring the United States into conformity with international standards for the protection of refugees established by the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status ofRefugees. See S. REP. No. 96-256, at 4 (1980), as reprinted in 1980 U.S.C.C.A.N. 141, 144.

[4] Between March 2020 and April 2022, Border Patrol expelled 1.8 million migrants under Title 42, the vast majority of whom came from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. John Gramlich, Key Facts About Title 42, the Pandemic Policy That Has Reshaped Immigration Enforcement at U.S.-Mexico Border, PEW RESEARCH CENTER (Apr. 27, 2022), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/04/27/key-facts-about-title-42-the- pandemic-policy-that-has-reshaped-immigration-enforcement-at-u-s-mexico-border/; see also Human Rights Watch, US: Treatment of Haitian Migrants Discriminatory (Sept. 21, 2021), https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/09/21/us-treatment-haitian-migrants-discriminatory (“Title 42 . . . singles out asylum seekers crossing into the United States at land borders – particularly from Central America, Africa, and Haiti who aredisproportionately Black, Indigenous, and Latino – for expulsion.”). Those expelled under Title 42 have faced life- threatening violence either in Mexico or in the countries from which they originally fled. See, e.g., Julia Neusner, A Year After Del Rio,Haitian Asylum Seekers Expelled Under Title 42 Are Still Suffering, HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST (Sept. 22, 2022), https://humanrightsfirst.org/library/a-year-after-del-rio-haitian-asylum-seekers-expelled-under-title-42-are-still-suffering/; Kathryn Hampton, Michele Heisler, Cynthia Pompa, & Alana Slavin, Neither Safety Nor Health: How Title 42 Expulsions HarmHealth and Violate Rights, Physicians for Human Rights (July 2021), available at https://phr.org/our-work/resources/neither-safety-nor-health/.

[5] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), A Mounting Asylum Backlog and Growing Wait Times (Dec. 22,2021), https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/672/; see also Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), Immigration Court Asylum Backlogs (Oct. 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/asylumbl/.

[6] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services operates ten asylum offices within the United States. See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Fiscal Year 2021 Report to Congress: Backlog Reduction of Pending Affirmative Asylum Cases, at 4 (Oct. 20, 2021), available at https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-12/USCIS%20-%20Backlog%20Reduction%20of%20Pending%20Affirmative%20Asylum%20Cases.pdf. The asylum offices are responsible for adjudicating affirmative asylum applications filed by asylum seekers who are not otherwise in removal or deportationproceedings. See 8 C.F.R. § 208.2(a)-(b).

[7] University of Maine School of Law, American Civil Liberties Union of Maine, and Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project, “Livesin Limbo: How the Boston Asylum Office Fails Asylum Seekers” (March 2022), available at https://mainelaw.maine.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/Lives-in-Limbo-How-the-Boston-Asylum-Office-Fails-Asylum-Seekers-FINAL-1.pdf (hereinafter “Lives in Limbo”).

[8] See id. at 3-4. The report’s authors analyzed data pertaining to asylum applications adjudicated by the Boston and Newark Asylum Offices between 2015 and 2020. Unfortunately, available data for decisions made since the end of 2020 suggests that the trends at the Boston Asylum Office have remained consistent. In the first quarter of 2022, the office’s approval rate remained at eleven percent. See U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs., I-589 Asylum Summary Overview, at 10, available at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf.

[9] Gregg A. Beyer, Establishing the United States Asylum Officer Corps: A First Report, 4 INT’L J. REFUGEE L. 455, 458 (1992).

[10] See Aliens and Nationality; Refugee and Asylum Procedures, 45 Fed. Reg. 37392, 37392 (June 2, 1980); Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 52 Fed. Reg. 32552-01, 32552 (Aug. 28, 1987); Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 53 Fed. Reg. 11300-01, 11300 (Apr. 6, 1988); Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 55 Fed. Reg. 30674-01, 30675 (July 27, 1990).

[11] Id. at 459.

[12] Gregg A. Beyer, Affirmative Asylum Adjudication in the United States, 6 GEO. IMMIGR. L.J. 253, 274 (1992).

[13] Id. at 268-69.

[14] See Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 55 Fed. Reg. 30674-01, 30680, 30682 (July 27, 1990) (to be codified at 8 C.F.R. pt. 208).

[15] Beyer, supra note 6, at 470.

[16] 8 C.F.R. § 208.1(b).

[17] U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS.: REFUGEE, ASYLUM, & INT’L OPERATIONS DIRECTORATE OFFICER TRAINING, INTERVIEWING – INTRODUCTION TO THE NON- ADVERSARIAL INTERVIEW, at 15-16 (Dec. 20, 2019), available at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/foia/Interviewing_-_Intro_to_the_NonAdversarial_Interview_LP_RAIO.pdf.

[18] 8 U.S.C. § 1229a(b)(1) (“The immigration judge shall administer oaths, receive evidence, and interrogate, examine, and cross-examine the alien and any witnesses.”).

[19] Compare Exec. Off. for Immigr. Review, Adjudication Statistics: FY 2022 ASYLUM GRANT RATES BY COURT, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1160866/download (showing an asylum grant rate of nearly 30% for the Boston Immigration Court in Fiscal Year 2022), with U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS., I-589 AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM SUMMARYOVERVIEW FY 2022 Q1 (OCT 1, 2021 – DEC 31, 2021), at 10, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf (showing an asylum grant rate of approximately 11% for the Boston Asylum Office in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2022). Many asylum offices have approval rates below that of the immigration courts. In fact, the most recent data reported by the Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse revealed that over three quarters of the asylum cases referred to the immigration courts by the asylum offices are granted. See Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Speeding Up the Asylum Process Leads to Mixed Results,” (Nov. 29, 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/reports/703/ (“Over three- quarters (76%) of cases USCIS asylum officers had rejected were granted asylum on rehearing by Immigration Judges.”).

[20] See Jasmine Aguilera, A Record-Breaking 1.6 Million People are now Mired in U.S. Immigration Court Backlogs, TIME, https://time.com/6140280/immigration-court- backlog/; TRAC Immigration, Immigration Court Backlog Now Growing Faster Than Ever, Burying Judges in an Avalanche of cases (Jan. 18, 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/675/;Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), Immigration Court Asylum Backlogs (October 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/asylumbl/.

[21] Interview with asylum attorney (November 2021) (“[My client is] having severe depression. This has derailed his life . . . I’ve never seen an individual on the brink of a nervous breakdown. I don’t know if he’ll survive this or overcome this.”).

[22] Data from the Newark Asylum Office provides a useful comparison because prior to the creation of the Boston Asylum Office, the Newark Asylum Office adjudicated affirmative asylum cases for the Boston region with a higher average grant rate than the Boston Asylum Office.

[23] U.S. Dep’t of State, Democratic Republic of Congo 2020 Human Rights REPORT (Mar. 30, 2021),https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/.

[24] Interview with asylum attorney (January 2022). See Interview with asylum attorney (August 2021) (“From my experiences with clients in the Boston Asylum Office, there seem to be people at the Boston Asylum Office who set the mindset against certain ethnic groups or nationalities. . . it’s like they default to ‘everybody’s a liar.’”); Interview with asylum attorney (November 2021) (stating that when he appeared in the Boston Immigration Court, some judges have asked why certain cases were referred from the asylum office, expressing exasperation that these cases are adding to the court’s backlog where they were clearly approvable at the affirmative level).

[25] This, in turn, leaves asylum seekers in legal limbo and drains government resources.

[26] Affirmative Asylum Procedures Manual, U.S. CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGR. SERVS., RAIO, Asylum Division, 27 (May 17, 2016), https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/guides/AAPM-2016.pdf (“It is not the role of the SAO to ensure that the AO decided the case as he or she would have decided it. AOs must be given substantial deference once it has been established that the analysis is legally sufficient.”).

[27] Interview with former supervisory asylum officer familiar with the Boston Asylum Office (November 2021) (explaining that the asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers initially hired at the Boston Asylum Office “tended to be people who did not grant [asylum] that much,” and noted that supervisory asylum officers are given “a lot of leeway” in refusing to give the asylum seeker the “benefit of the doubt.”).

[28] U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS., I-589 AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM SUMMARY OVERVIEW FY2022 Q1 (OCT 1, 2021–DEC 31, 2021), at 12, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf (listing the Boston Asylum Office’s affirmative asylum caseload as 20,900 as of December 31, 2021). Backlogs in asylum cases are not unique to the Boston Asylum Office. Nationally, the backlog reached a “historic high” during the Trump Administration, with over 386,000 pending applications by the end of fiscal year 2020. HUM. RTS. FIRST, PROTECTION POSTPONED: ASYLUM OFFICE BACKLOGS CAUSE SUFFERING, SEPARATE FAMILIES, AND UNDERMINE INTEGRATION 1-4 (Apr. 9, 2021), https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/ProtectionPostponed.pdf.

[29] Interview with former supervisory asylum officer (November 2021) (“The abuse or temptation to short circuit and not do a full-fledged asylum interview is great for officers who have a tremendous backlog.”); Interview with former asylum officer (December 2021) (“There is a perverse incentive to rush through cases. Asylum officers have a stack of cases and they must turn them around quickly . . . We interview so many applicants with similar claims and many of us ended up recycling decisions, plugging in new facts and doing similar credibility assessments.”).

[30] Interview with former asylum officer (December 2021) (“This response is absolutely part of the trauma asylum officers hold from doing this work . . . Asylum officers are just exhausted. We are hearing stories of torture and abuse, often involving children, and it’s really exhausting and there’s no real support or even acknowledgement of the impact on us.”).

[31] 8 C.F.R. § 208.1(b); see also U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS.: REFUGEE, ASYLUM, & INT’L OPERATIONS DIRECTORATE OFFICER TRAINING, INTERVIEWING – INTRODUCTION TO THE NON-ADVERSARIAL INTERVIEW, at 15-16 (Dec. 20, 2019), available at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/foia/Interviewing_-_Intro_to_the_NonAdversarial_Interview_LP_RAIO.pdf (instructing that AOs are “neutral decision-maker[s]” and thus must maintain a “neutral and professional demeanor even when confronted with . . . a difficult or challenging [asylum seeker] or representative, or an [asylum seeker] whom [the AO] suspect[s] is being evasive or untruthful”).

[32] Former asylum attorney interview (November 2021) (“The client was a survivor of torture and [the officer] laughed multiple times throughout the client telling her story . . . She checked her test messages during the interview . . . The [applicant] was pouring his heart out to this person and she’s laughing . . . and yet when she is engaged, she’s cross examining him up and down.”).

[33] Interview with asylum attorney (January 2022) (“Questions seemed to be a direct way to suggest that the client was not credible . . . it was completely unnecessary and not relevant and really insensitive to the fact that [the client] was super traumatized and trying to recount horrific details about violence they experienced.”).

[34] See U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS., I-589 AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM SUMMARY OVERVIEW FY2022 Q1 (OCT 1, 2021 – DEC 31, 2021), at 12, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf (listing number of pending asylum cases in each asylum office as of December 31, 2021).

[35] See Archive of Press Release, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., USCIS to Take Action to Address Asylum Backlog (Jan. 31, 2018), available at https://www.uscis.gov/news/news-releases/uscis-take-action-address-asylum-backlog. The LIFO policy was implemented by the Trump administration, “to deter those who might try to use the existing [asylum] backlog as a means to obtain employment authorization,” id., and remains in effect today. See U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., Affirmative Asylum.

Cover image credit