Apr 28, 2019 | Essays, Online Scholarship

By Doug Cassel

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights is one of several international human rights bodies actively undermined by the current U.S. Administration. Disrespect for the Commission is a gross miscalculation. It disserves both our values and our interests.

The Commission is the human rights watchdog of the Organization of American States. Its seven members are elected by the 34 participating governments of the OAS to serve in their personal capacities as experts. The Commission processes complaints; publishes hard-hitting reports; requests governments to adopt precautionary measures; refers and litigates cases against the 22 mostly Latin American States which accept the contentious jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights; facilitates friendly settlements; and issues press releases denouncing human rights reversals and lauding advances.

In recent months, for example, the Commission’s advocacy may have played a role in the release of one hundred protesters from prison in Nicaragua and was instrumental in securing a UN Human Rights Council resolution condemning serious human rights violations in that country.

With its wide-ranging powers collectively conferred by governments, the Commission is the most authoritative and credible human rights body in the Western Hemisphere. Past U.S. Administrations have nearly always supported it. They understood that encouraging respect for human rights in the Americas not only promotes our values, but also stimulates economic development, while helping to avoid wars, civil strife, and refugee flows.

Hence the United States funds most of the Commission’s regular budget. We nominate U.S. citizens for election by OAS member States to serve on the Commission. We urge other governments to participate in Commission proceedings.

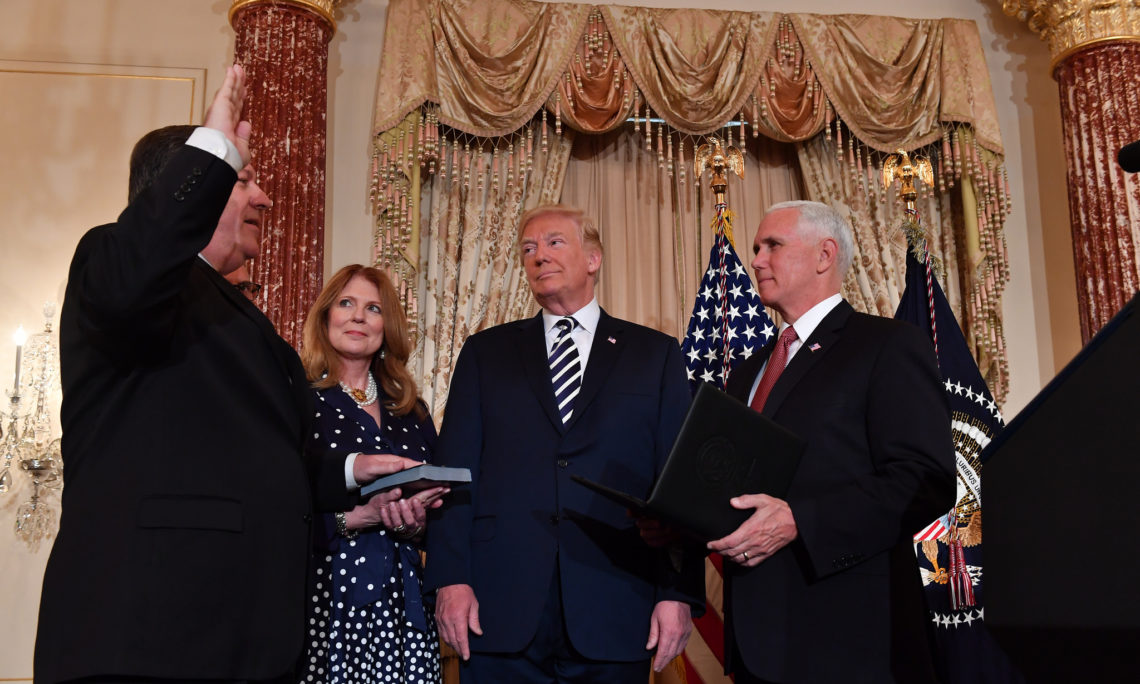

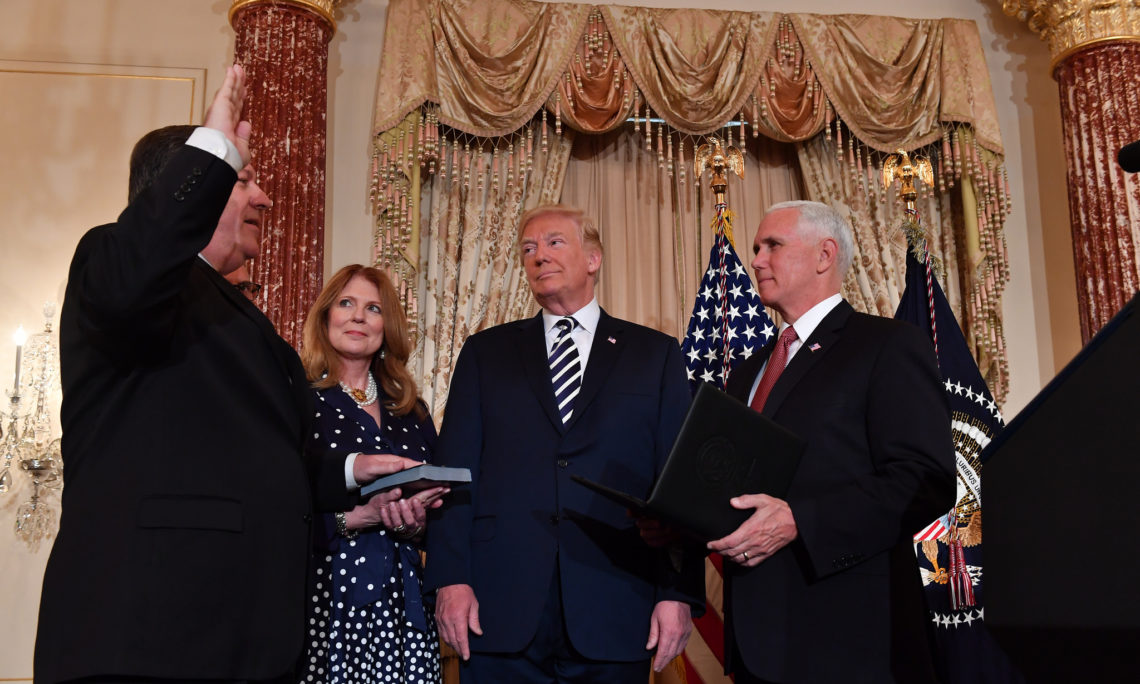

But enter the current Administration. Its first step was to instruct our diplomats not to attend Commission hearings on two sensitive cases against the US. Our boycott put us in the company of only two other countries: Cuba and Nicaragua.

In June 2017 the candidate nominated by the State Department for election to the Commission (this writer) was defeated. Senior Department officials lifted nary a finger to win the election.

That same month, Republican Senators Ted Cruz and Mike Lee published an op-ed calling on the Trump Administration to reassess U.S. funding of the OAS, because of the Commission’s positions on abortion and gay marriage.

Later that year, the first budget under the Trump Administration was adopted. The United States paid its assessed quota of about $50 million toward the total OAS budget of about $83 million. However, because the regular OAS budget for the Commission is woefully inadequate (only about $5 million to $7 million annually), the Commission depends on additional voluntary contributions. In 2015, the US had voluntarily contributed an additional $2 million to the Commission; in 2016, $3.2 million; and in 2017, $2.7 million. In 2018, under the new Administration, the United States contributed zero.

In December 2018, Cruz, Lee and seven other anti-abortion Senators asked Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to cut off all US funding of the Commission, because of its support for women’s reproductive rights.

Whatever one’s position on that contentious issue, the Senators’ proposed remedy – a total cut-off of US funds – was grossly disproportionate. For example, of 259 press releases issued by the Commission in 2018, only one focused on abortion. In contrast, 41 focused on repression in Nicaragua, 12 on Venezuela, 12 on Guatemala, six on Honduras, and 43 on acts of murder or violence in other countries.

In March 2019 Secretary Pompeo responded to the Senators by firing what may be a warning shot at the Commission. The State Department announced a cut of $210,000 in funding for the OAS, equivalent to about 5% of US funding for the Commission.

Shortly before this announcement, in February, the United States again boycotted a Commission session. And in March the United States let pass the deadline without nominating a candidate to serve on the Commission.

At a time when human rights crises overwhelm several countries in the Americas, the Commission’s work is of critical importance. We must hope that future Administrations will once again appreciate the Commission’s vital role in our troubled hemisphere.

Apr 4, 2019 | Essays, Online Scholarship

Editor’s Note: The following piece is a reflection from Georgetown Professor David Koplow on the space law panel he moderated at our International Law Symposium on March 9, 2019.

The panel on “The Future of Planetary Defense and International Law” addressed the provocative legal, scientific, and policy questions regarding what should be done if it is discovered that a large asteroid is on a collision course with Earth?

This problem is significant because: a) we know that asteroids do strike the planet all the time, although most of them are too small to notice or care about; and b) an impact by a large asteroid could, depending upon its size, composition, and other factors, cause devastation on a local, regional, or even global scale. At the moment, there is no known such threat on the horizon, but astronomers acknowledge that they are currently unable to detect, identify, and track a large number of potentially hazardous objects. Even more worrisome, humans have no tested, reliable, in-place capability for promptly and effectively responding to such a danger, especially if it were detected with little advance warning time.

In response, NASA and its counterpart space agencies in other countries have undertaken efforts to survey the population of near-Earth objects and to develop techniques that could be employed to deflect a dangerous intruder. Sophisticated experiments are underway or planned to study the nature and characteristics of asteroids and to explore mechanisms for altering their trajectories – but these are far from completion.

Although the subject of planetary defense lies overwhelmingly within the realm of science and technology, there are interesting and important legal aspects, too, and the panel addressed two of special note.

The first legal conundrum arises from the possibility that one conceivable technique for attempting to alter the trajectory of an oncoming asteroid would be to employ the vast power of a nuclear explosion on, inside, or near it. Indeed, if the warning time were short, that may prove to be the only effective deflection technique. However, key provisions in some important, long-standing, and widely-adhered-to treaties stand in the way. These instruments were crafted with problems vastly different from planetary defense in mind – they were designed to pre-empt a nuclear arms race in space, and they have proven remarkably successful in foreclosing what could otherwise have developed into a dangerous and destabilizing exoatmospheric competition. The difficulty in reconciling these very distinct types of objectives – dodging an oncoming asteroid and foreclosing additional military applications in space – may prove to be a severe international challenge.

A second principal legal issue arises from the possibility that an attempt to divert an asteroid might, unfortunately, prove to be only “partially” successful. Suppose that the human intervention was unable to maneuver the asteroid sufficiently to make it miss Earth altogether, but did serve to alter its trajectory somewhat, so that it impacted Country X, instead of Country Y, where it would have struck if nothing had been done. Under applicable treaties, a country has “absolute” liability for damage caused on the surface of the Earth by its activities in space. That legal standard could result in an enormous exposure – the state(s) that in good faith exercised their best efforts to try to save the planet from an impact might incur an enormous financial responsibility for all the harm suffered by Country Y.

The most promising route considered by the panel for addressing both these legal issues is to exercise the powers of the United Nations Security Council. Under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter, the Security Council holds a unique law-making ability, and possesses the authority to supersede the provisions of other treaties. If prompted by a genuine emergency, the Security Council could therefore authorize states to exert their best efforts for planetary defense, notwithstanding the provisions of the arms control treaties and it could likewise modify the usual liability standards. Of course, it will not be easy or automatic to draft suitable provisions that would deftly address the dangers and the costs without unleashing an unwanted arms competition and without leaving Country Y to fend for itself in response to a catastrophe.

David A. Koplow, Professor of Public International Law and National Security Law at Georgetown University Law Center

Feb 6, 2019 | Content, Essays, Online Scholarship

By Flávia Piovesan and Julia Cortez da Cunha Cruz

Latin American and Caribbean countries are among the most violent and unequal nations in the world. Only 8% of the global population, the region accounts for 37% of the world’s homicides. At the same time, of the twenty most unequal countries in the world, six are located in Latin America. While democratization has strengthened the protection of citizens’ rights, countries in the region still need in-depth institutional reforms to consolidate the rule of law, end impunity, and fulfill human rights.

The Inter-American Human Rights System could play a role in addressing these challenges. Over the past 50 years, both the Inter-American Commission and Court of Human Rights have turned the emancipatory promises of human rights law into concrete social change. They have destabilized dictatorial regimes, commanded an end to impunity during democratic transitions, and contributed to the protection of vulnerable groups. However, in order to overcome today’s challenges, the system can learn from its past: Which cases were the most successful in transforming national realities? Which ones were not? What can we do to foster the implementation, effectiveness, and impact of its decisions?

Inter-American institutions have taken steps in this direction, seeking to improve case monitoring and producing knowledge about implementation. In 2017, the Commission signed a cooperation agreement with Paraguay to develop a regional system that systematizes its recommendations and monitors their implementation. That same year, the Commission created the Special Program to Monitor IACHR Recommendations with the aim to develop roadmaps for compliance. Among other proposals, the Commission is looking into adopting indicators to monitor the implementation process, as well as scaling up the strategy of in loco missions.

As a complement to these initiatives, the system should start measuring the impact of its decisions over the region. It could approach this issue from different angles – for example, one could count the number of public ceremonies in which states publicly recognized their responsibility for human rights violations, or calculate the total value that states have paid as compensation to victims of abuse. Among these possibilities, our suggestion focuses on a form of measurement that captures the unique role played by the Inter-American System in advancing structural human rights reforms. This form of measurement will demonstrate that the system not only saves individual lives, but also fosters long-lasting changes.

In response to the abovementioned challenges and needs, we champion the creation of an Observatory of Structural Impact fostered by the Inter-American Human Rights System. The Commission has unanimously approved the idea and will launch the observatory later this year. It will be a participatory and dynamic platform, dedicated to identifying structural transformations triggered by the system. The observatory will encompass both normative changes and the adoption of human-rights-based public policies. This type of impact is measurable – and once the observatory starts analyzing it, we may be able to identify drivers of structural transformation. The system can then use this information to maximize the positive impact of its decisions, strengthening democracy, the rule of law, and the protection of human rights in the region.

In the 50th anniversary of the American Convention on Human Rights, we believe there is no better tribute to its founding ideals.

Flávia Piovesan, member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and Professor of Law at the Catholic University of São Paulo

Julia Cortez da Cunha Cruz, human rights lawyer at the NGO Conectas

Jan 28, 2019 | Content, Essays, Online Scholarship

By Gerald L. Neuman

The International Criminal Court (ICC) makes headlines around the world when it issues its occasional judgments. But most of the work of fighting impunity for severe crimes condemned by international law depends on national enforcement. Two separate efforts are currently underway to strengthen international cooperation in ensuring national prosecution: 1) a multi-year project of the International Law Commission (ILC) to draft articles for a future convention on the prevention and punishment of crimes against humanity, comparable to the existing Genocide Convention and Convention Against Torture; and 2) an episodic state-led initiative to draft a mutual legal assistance treaty for the most serious international crimes. The Human Rights Program at HLS recently convened a private workshop to discuss the vitally important ILC project.

A key issue in establishing state obligations to prosecute international crimes involves the choice of a definition that is appropriate to the obligations that are being imposed. The notion of “crimes against humanity” has a long history, but its definition has evolved over the years. The definition negotiated for the Rome Statute, which created the ICC—an international tribunal with a limited capacity to prosecute and adjudicate—may not provide the right definition for an obligatory system of consistent national prosecution.

The Rome Statute enumerates (section 7) ten offenses amounting to crimes against humanity, plus a residual category for comparable inhumane acts. Some of these offenses are self-evidently atrocious, like extermination, while others cover a broad range of conduct, like imprisonment and deportation. The whole enumeration is subject to a “chapeau” element intended to justify regarding them as severe, namely that the action is performed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack. A particular defendant need only have performed a single instance of the conduct to be guilty of a crime against humanity; much of the opprobrium for low-level perpetrators arises from the fact that they have participated in a large-scale attack on civilians.

Unfortunately, the pivotal term “attack” received a seemingly formalistic definition in section 7. Taken literally, no physical violence is necessary for an attack, but merely multiple instances of any conduct on the list, pursuant to a state policy. Commentators have pointed this out, but the ICC has not had occasion to give a narrowing interpretation. After all, only extreme situations come before the ICC. Not only is the Court’s capacity limited to a small number of cases—the Rome Statute also restricts the pool by requiring a finding that the case is of sufficient gravity to justify the Court’s attention.

What works for a court of such limited jurisdiction may not be suitable for a treaty obligating states to pursue comprehensive enforcement. The issue is not worrisome in regard to the offense of extermination, but it becomes problematic in regard to the offense of imprisonment in violation of fundamental rules of international law. Past decisions have read such language broadly, to include detention that complies with national law if the national statute violates an international human rights norm. International tribunals have had little incentive to restrict this definition when the detention occurs in connection with a genuine violent attack on civilians. The criminal code of Australia spells out the standard for imprisonment as met by any violation of articles 9, 14, or 15 of the International Covenant on Civil Rights. The result could be that a disproportionate policy of pretrial detention, which is common in many countries, amounts as such to a crime against humanity and that states are obliged to prosecute the judges and jailers who implement it.

The designers of a future treaty on crimes against humanity need to deal explicitly with this definitional issue and its consequences. One possibility would be to clarify or revise the definition of an “attack” for purposes of the treaty. Similarly, other safeguards could be adopted to countervail against the borrowed definition. One cannot simply rely on prosecutorial common sense to eliminate the problem in practice, for several reasons. First, the ILC project would also enable nonnationals to raise the risk of falling victim to a crime against humanity as an absolute defense against removal. And in some countries (though not Australia), the criminal justice system will enable private prosecution of crimes against humanity. This important new treaty needs a solution appropriate to its context.

Gerald L. Neuman is the J. Sinclair Armstrong Professor of International, Foreign, and Comparative Law, and the Co-Director of the Human Rights Program at HLS. He teaches human rights, constitutional law, and immigration and nationality law. His current research focuses on international human rights bodies, transnational dimensions of constitutionalism, and rights of foreign nationals. He is the author of Strangers to the Constitution: Immigrants, Borders and Fundamental Law (Princeton 1996), and co-author of the casebook Human Rights (with Louis Henkin et al., Foundation Press).

Nov 16, 2018 | Content, Essays

The frontiers of international law are shifting. From climate change to corruption, we have seen a positive expansion of global norms. This year, ILJ will be soliciting 500-word think pieces tracing emerging trends in public and private international law. These “Frontiers” pieces are designed to spark conversation about exciting new developments in international law as well as worrisome setbacks in cases where enforcement has dropped or norms undermined.

We’ll be soliciting these reflections from leading scholars in the international law field starting in Spring 2019.