Michael Yip*

I. Introduction

In October 2023, two dozen countries gathered in Beijing to celebrate the Belt and Road Initiative’s (“BRI”) tenth anniversary. However, in ten years, little is understood about the bank loans that finance this initiative. On the one hand, the loans have been described as “debt traps” or “unsettling” projections of Chinese geo-economic power. On the other, the BRI has been characterized as an “international public good” or—in the words of the UAE’s Economy Minister—even “a gift to the world.” Naturally, both approaches—particularly when taken in isolation—are oversimplifications.

1. The Value of a Legal Perspective

Adopting a legal lens, however, would materially enrich our understanding of how BRI loans work in practical and empirical terms—enabling us to “look behind the headlines.” One aspect that has been overlooked is the “invisible law” that governs the loan agreement and disputes arising from the loan. Although this law—codified in the loan agreement’s choice of law, jurisdiction, and procedural law clauses—is an indispensable (albeit “boilerplate”) part of any banking contract nowadays, it has acquired an added significance in BRI loan documents. These clauses have become a venue in which different legal regimes—Chinese, English, New York, and others—project legal power and jostle with one another to shape China’s global development financing initiative (which itself goes on to project power and compete for prominence and acceptance in international affairs).

2. Key Findings

The data presented below shows that, based on the text of BRI loan agreements, Chinese law and dispute resolution mechanisms have been an increasingly popular choice. This indicates a characteristic of the BRI to induce “extraterritorial observance”: a shorthand term used by this article to describe the patterns and processes by which national laws are—as a matter of common and expected practice—observed by persons outside the country from which the laws originate. (In this case, Chinese law happens to be the object of extraterritorial observance, but history tells us that—because of processes such as globalization, migration, revolution, and colonialism—Soviet, Islamic, English, New York, and European Union laws have undergone a comparable experience.)

However, taking what the clauses in BRI loan agreements expressly say at face value would lose sight of the fact that they govern the loan in ways that cannot immediately be evident upon a cursory reading of the loan documentation. In other words, the governing laws have been—to a material extent—“invisible.” This is for three reasons. BRI loan agreements have often been kept secret; the depth, breadth, and content of the governing law have not been fully enunciated in the loan agreement; and some of the governing law may be found elsewhere in the laws of other countries.

3. Article Roadmap

This article will first explain the origins of the contest between legal regimes; describe the extraterritorial observance of Chinese law; and explain what makes the law governing BRI loans both consequential and invisible, before concluding thereafter.

These considerations are not merely academic. Indeed, when BRI projects go wrong, the “invisible law” determines how China and its borrowers will work out problems—on which, according to Christoph Nedopil, over a trillion dollars of taxpayers’ money, citizens’ livelihoods, and geo-economic power are staked.

II. Does a Competition Between Legal Regimes Exist?

At first glance, a competition between legal regimes may not appear to exist. After all, BRI loan agreements—and their clauses—constitute the final product of a negotiation and documentation process between the borrower and lender, supported by legal and financial advisers. Given this, any “competition” most visibly lies between the loan parties, rather than different legal regimes. This interpretation is supported by Ian Ivory and Cora Kang, who—in their book on the use of English law in BRI transactions—suggested that negotiations may be won or lost as part of a quid pro quo: “Where the question of using PRC law is sometimes raised, this is usually as a tool in negotiations and is traded for some other concession on the deal.”

However, the English judiciary and bar associations published a position paper titled: The Strength of English Law and the UK Jurisdiction. This paper advocated for the predictability of English law, claiming that it “respects the bargain struck by parties” and “will not imply, or introduce, terms into the parties’ bargain unless stringent conditions have been met.” Were disputes to arise, the paper also advocated for the UK’s “incorruptible judiciary” that was described as “structurally and practically independent.”

Those comments were made in 2017, attempting to provide reassurance and bolster confidence that—even after the UK’s departure from the European Union—English law was still suitable to govern cross-border contracts and English judges could still be trusted to adjudicate cases. Although the context of these comments, Brexit, is salient, they are just as applicable to the BRI—which at that point was still in its relative infancy (at four years old) and was, according to sentiment analysis conducted by Bruegel, better able to court interest in the West.

At the time, the judiciary’s and bar association’s comments also formed part of a broader set of advocacy messages by the UK state. They include 2016 remarks by the UK Advocate General for Scotland—a member of the executive branch—which emphasized the value of the UK’s law enforcement and legal services on the Belt and Road. In this light, both sets of comments can be cast as an example of one legal regime attempting to maintain its competitiveness in what Gilles Cuniberti called an “international market for contracts” and (by extension) for BRI loan agreements too. To those ends, there is no reason not to include initiatives such as the BRI as a plausible means to maintaining competitiveness in Cuniberti’s “market.”

By contrast, attempts by the Chinese legal regime to extend (rather than, in the English case, maintain) competitiveness have assumed a different form. Rather than an enticement-led approach (through position papers and other marketing campaigns), China’s approach has been directive-based and action-oriented. For example, the Opinions of the Supreme People’s Court on Further Providing Judicial Services and Guarantees by the People’s Courts for the Belt and Road Initiative stated that: “The people’s courts shall extend the influence of Chinese laws… and strengthen the understanding and trust of international businesses on Chinese laws.”

III. The Competition and “Extraterritorial Observance” in Numbers

To date, no attempt has been made to measure the contest between legal regimes to govern BRI loans. However, original analysis of AidData’s loan agreement repository undertaken by the author reveals the extent to which the BRI is inducing the extraterritorial observance of Chinese law.

1. Choice of Law Clauses

Choice of law clauses set out “the law that applies when interpreting the agreement and in determining any disputes regarding it.” A typical formulation of the clause can be found in the 2017 loan agreement signed between China and Sierra Leone that financed the upgrade and expansion of the Queen Elizabeth II Port, which reads as follows: “This Agreement and the rights and obligations of the parties hereunder shall, in all respects, be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of China.”

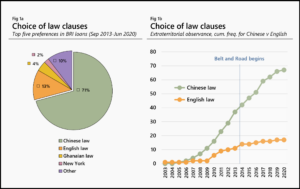

Fig. 1a shows the composition of choice of law clauses occurring in 48 loan agreements entered into by Chinese banks and overseas borrowers following the inception of the BRI. As shown, Chinese law has emerged as the dominant choice by 2020 (71%). However, this observation runs contrary to common practice of selecting a choice of law originating from a third country. This practice has been described by Philip Wood in a 2016 book commemorating the Loan Market Association’s twentieth anniversary as important “not because of familiarity or commercial orientation or any of those soft virtues, but rather to ensure that the loan obligations were insulated against changes to the loan agreement by a statute of the sovereign.” Philip Wood went on to indicate that such changes could include passing legislation to “forcibly” impose a debt moratorium, a debt rescheduling or a foreign exchange control of the loan currency. The primacy of Chinese choice of law clauses, however, most likely reflects Matthew Erie’s and Sida Liu’s view that China, as a “capital exporter, may occupy a dominant bargaining position vis-à-vis the host state.”

Fig. 1b shows the cumulative frequency of choice of law clauses in 101 Chinese-financed loans from 2003 to 2020. As shown, the adoption of Chinese choice of law clauses increased by 1.8 times from the BRI’s inception in 2013 onwards, whereas the same for English choice of law clauses grew by 1.5 times. This rate of adoption has meant that Chinese law clauses not only maintained but also enlarged their extraterritorial observance over time. English law clauses—the first-choice common law preference but nonetheless the second-choice overall—was unable to challenge Chinese law primacy, instead entering into a plateau that by 2020 had not yet been reversed.

2. Jurisdiction Clauses

Jurisdiction clauses “deal with the physical location of where a dispute will be heard, the type of institution (Court or Arbitration Tribunal) that will hear the dispute.” In practice, these clauses will often mimic choice of law clauses because, as Philip Wood noted in relation to syndicated loan agreements: “Once the governing law had been chosen, jurisdiction followed suit since the benefits of an external governing law might well be lost if the courts that enforced it were different, even though technically most courts could then, as now, apply foreign law.”

However, Chinese lending has produced noteworthy exceptions. In the pre-BRI era, an illustrative example is a RMB32 million loan provided by the Export-Import Bank of China (“China Eximbank”) to the Botswana Ministry of Finance and Development Planning for a housing project in the capital. In that loan agreement, the parties agreed upon an English governing law, but elected that disputes would be submitted to the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (“CIETAC”). In the AidData repository, other noteworthy hybrid combinations during the BRI era include a US$219 million loan provided by China Eximbank to the Philippine Department of Finance for the “Philippine National Railways South Long Haul Project.” In the loan agreement, Chinese governing law was chosen but the dispute resolution seat was the Singapore International Arbitration Centre.

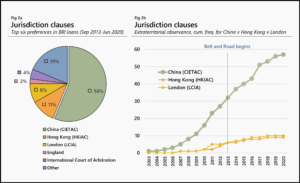

Fig. 2a shows the composition of jurisdiction clauses, which have aggregated variants such as different physical locations for the same arbitration tribunal or alternative venues if an urgent decision is required. However, as with the case of choice of law clauses and irrespective of the permutations on offer, the preference for the Chinese option—CIETAC—has been dominant (56%). In transactions for which a jurisdiction clause was ascertainable, the London Court of International Arbitration and Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre were in close contention, respectively competing for second and third place.

Fig. 2b shows the cumulative frequency of jurisdiction clauses. As shown, the adoption and extraterritorial observance of Chinese jurisdiction clauses grew by 1.8 times from the BRI’s inception in 2013 onwards. This growth rate mirrors the rate for Chinese choice of law clauses (discussed above), which indicates that the “hybrid combinations” discussed above were outliers rather than the norm. Meanwhile, Hong Kong jurisdiction clauses grew by 1.5 times and those of London grew by 1.7 times.

3. Procedural Law Clauses

Procedural law clauses stipulate the rules by which the dispute resolution seat will administer the adjudication of the dispute. In practice, these clauses will often mimic jurisdiction clauses because—where national courts have been nominated—compliance with their procedures tends to be mandatory. For example, litigants in Chinese and English courts must follow the civil procedure rules for each country in order for their case to be tried. However, the rules of arbitration tribunals give an established right to choose and/or modify the procedural law governing their arbitration.

The “right to choice” in a BRI arbitration context is demonstrated by an US$85 million loan provided in 2010 by the CITIC Bank and China Construction Bank to the Argentinian Ministry of Economy and Public Finance to finance construction of and supplies to the Lina-A Metro in Buenos Aires. In that loan agreement, the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre was given jurisdiction, but the procedural law chosen by the parties was that of the U.N. Commission on International Trade Law.

What both transactions show is that there is substantial flexibility in the contractual terms governing procedural law – but only where arbitration is concerned. Furthermore, no loan agreements substituted the procedural law of one national arbitration tribunal for those of another national arbitration tribunal. No transaction, for example, gave jurisdiction to the London Court of International Arbitration but chose the procedural law of a Chinese arbitration tribunal. Instead, where substitutions have occurred, they have swapped the procedural law of a national tribunal with multilateral procedural law formulated by an international organization.

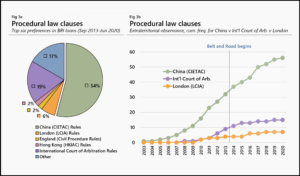

Fig. 3a shows the composition of procedural law clauses. As with the choice of law and jurisdiction clauses, the preference for the Chinese option—the rules of CIETAC—has been dominant (54%). Fig. 3b shows the cumulative frequency of procedural law clauses. As shown, the adoption and extraterritorial observance of Chinese procedural law clauses grew by 1.8 times from the BRI’s inception in 2013 onwards.

IV. The Laws are Consequential but Operate “Invisibly”

1. On Consequentiality

The laws described above are consequential in three ways. First, they serve as a gateway for troubled transactions and parties in dispute to seek support from judges and arbitrators on contested points of law. As the BRI matures and moves into its second decade, loan transactions will enter rougher waters and the three clauses discussed will come to the fore—especially as China is pushing to play a more active dispute resolution role in the international legal order through the China International Commercial Court. Doing so enables China to place less reliance on resolving problems through ad-hoc diplomatic channels, as was recently seen when Zambia restructured US$4.1 billion of debt owed to China.

Second, the clauses serve as conduits for extraterritorial observance and channel the legal power that countries exert on each other. The impact of these clauses is at their most pervasive when individual jurisdictions (such as England, New York and—increasingly—China) shape the international legal order to induce others from overseas to voluntarily observe their laws or, alternatively, their approach to the practice of law. For instance, the English jurisdiction, through its Loan Market Association, promulgates standard-form loan agreements—that have often been English law-governed – to lenders and borrowers of all origins. So, in a similar vein, could a standard-form template for BRI loans materialize one day? Possibly. In their landmark work How China Lends, Anna Gelpen et. al. have already identified emergent patterns in clauses covering events of default, confidentiality duties and repayment mechanisms across 100 Chinese loan agreements. However, notwithstanding that those patterns are—in their 2024 form—unlikely to constitute a self-standing BRI template, templates materialize slowly. By way of illustration, Philip Wood recollected that the first syndicated loan agreement governed by English law may have drafted in 1968. Since then, it has accumulated nearly 60 years of updates and modifications. Building a template takes time. Let us wait and see.

Third, the clauses—and their propensity to nominate one choice of law or jurisdiction to the exclusion of others—drive and divert significant amounts of business for law firms. Over a longer time horizon, the BRI may go on to bring many millions of dollars of business to the law firms with the capability to advise on Chinese law matters. These law firms include both “home-grown” Chinese firms as well as international outfits that have entered into joint ventures with Chinese partners.

2. On “Invisibility”

Yet, the law governing BRI loan agreements operates invisibly and in ways that a mere examination of the documents would not reveal. It does so in three ways. First, as Anna Gelpern et. al. have discovered, BRI loan agreements contain “far-reaching” confidentiality clauses that restrict the borrower’s ability to disclose information about the loan. (This differs with commercial practice, in which it is typically lenders who have been prevented from disclosing confidential information, primarily to uphold borrower privacy.)

Second, the content of the law and the situation-specific rules governing BRI agreements will not be fully enunciated in the three clauses. The clauses cannot (and simply do not have the space to) articulate the legal rule for a complete universe of legal problems that may arise in relation to the loan. Accordingly, at best, the clauses serve as signposts to very large bodies of law, which in turn require further expertise to understand and apply. (Furthermore, the varying levels of comprehensiveness and depth of codification within the Chinese, English and other legal systems will not only add further complexity to ascertaining the proper legal rule, but also subject that ascertainment to interpretation and/or modification by judges.) In this sense, the governing law of a BRI loan may not only be invisible to the reader of loan agreement, but also uncertain.

Third, although parties to a BRI loan generally have the autonomy to select their own choice of law, this may be (or attempt to be) overridden by a foreign mandatory law that is “unseen” and on which the text of the loan agreement was silent. For example, in the case of loans governed by Chinese law and involving a private borrower, plausible mandatory laws—as noted in 2022 by Philip Wood—most likely include the borrower country’s insolvency laws. These could conflict with a Chinese governing law expressly chosen by the parties if the borrower entity became insolvent and claims on borrower assets were made by creditors. (The same, however, would not apply to sovereign borrowers who would instead be caught between an expressly-chosen Chinese governing law and soft international obligations such as Paris Club rules.) Elsewhere, a similar (albeit more indirect) example arises in the field of environmental law. A borrower country’s planning and environmental laws would apply to government licences which, in turn, would be required to develop a site into a project and which would typically be listed as part of conditions precedent to the loan being drawn down by the borrower. Finally, with respect to loans governed by a non-Chinese law, plausible sources of mandatory Chinese law include the “social public interest” exception to party autonomy. Given that mandatory laws of any jurisdiction present a “hidden minefield” to BRI parties, their advisers would do well to acquaint themselves with Chinese and non-Chinese approaches to conflict of laws.

V. Conclusion

There is a contest between legal regimes to be attractive and to—wherever and whenever possible—be taken up and observed by international commercial parties. This contest has long predated the BRI. However, the loan agreements underpinning China’s initiative serve as a new arena for contestation in which a new alternative—China’s laws and dispute resolution mechanisms—show early signs of taking primacy over more established alternatives from North America and Europe. The consequences of this “extraterritorial observance” are significant: a legal regime’s entrenchment and prominence in transactions tends to sustain itself, by setting the norm for future transactions and/or by governing the forthcoming disputes. In turn, extraterritorial observance precipitates more business activity for its lawyers. For practitioners, this can indeed be a virtuous cycle.

However, the laws governing BRI loans operate invisibly. As has been the case with any complicated transaction pre-dating the BRI, it may be difficult to ascertain which loans are governed by which laws; which doctrines of expressly-chosen laws apply; and how local laws may mandatorily override the choice of the parties. One day, these laws could be called upon to determine the outcome of the very first BRI banking dispute. Such a dispute will plausibly place billions of dollars at risk; materially shape the direction of BRI lending practices; and bring about the collision of law against another. For these reasons, how invisible laws govern bank loans on the “Belt and Road” deserve an ever-watchful eye.

*Michael Yip is a Research Associate in “China, Law and Development” at the University of Oxford, where he is also the Research Cluster Lead for legal services. Previously, he was a British civil servant and worked at the World Bank’s Legal Vice Presidency, specialising in export and infrastructure finance. Michael also holds an LLM as a Yenching Scholar from Peking University in China.