Extraterrestrial Accountability and the Parella Stakeholder Management Approach

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a four-piece symposium that examines Kishanthi Parella’s work, “Enforcing International Law Against Corporations: A Stakeholder Management Approach,” featured in Volume 65(2) of the HILJ Print Journal.

*Monika U. Ehrman

I. Introduction

Corporate secrecy is not a new phenomenon. Companies routinely take steps to ensure that prized information is secured and kept from competitors. Securing intellectual property as trade secrets keeps the information confidential for as long as the owner employs reasonable measures to guard the information—unlike patents, which offer term protection of certain types of intellectual property in exchange for public registry. Geographical and geological location data are especially lucrative for mining and petroleum companies, which target mineral resources for extraction and production. So, it is not unexpected that space mining companies would want to do the same. But should they be able to do the same is another question.

In December 2023, AstroForge, a private company, announced a proposed launch to surveil an asteroid for commercial mining. Formed from the remains of planetary and other debris following the creation of the solar system over 4.5 billion years ago, asteroids are small outer space objects that orbit the Sun. Not only do they contain insightful information about the birth of our planet and the possible origins of life, but they may also be financially valuable. Some asteroids contain high ore content of minerals that are rare or critical to modern technologies. So, it is not surprising that AstroForge wants to mine an asteroid. Which one? We do not know—the company does not want its competitors to find out.

Why should it matter that AstroForge will not disclose its intended extractive target? Because its target is in outer space—the province of all humankind. As such, does everyone on Earth own what AstroForge and extraction companies like it mine? That part is not clear to everyone. However, what is more clear is that any disputes over these asteroids or other outer space bodies are governed by international law, including such landmark treaties as the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Agreement. And international law governance prevails where state actors carry out various duties in the international forum. In the case of space, almost all major actions are performed by governmental entities. But that is about to change.

Private entities, such as AstroForge, represent a new brand of space explorer—they are private sovereigns. They hold loyalty not to the nation, but to the investors. And therein lies the challenge with international law as the primary mechanism to govern private sovereign behaviors. Professor Kishanthi Parella explains, “Many corporate actors do not abide by international law because the international legal order lacks adequate mechanisms to ensure their compliance.” So how can one control the behavior of extraction companies in outer space? In her innovative Harvard ILJ article, Enforcing International Law Against Corporations: A Stakeholder Management Approach, Parella proposes we apply principles of corporate stakeholder governance to international law, by using non-state actors as a mechanism to force good corporate behaviors. This innovative approach offers success in challenging hybrid environments such as outer space.

II. Current Authority to Govern Potential Space Mining Activities

Scholars generally analyze outer space governance under the existing rubric of international law, which mainly consists of the: (i) 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Outer Space Treaty”), (ii) 1968 Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Rescue Agreement”), (iii) 1972 Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects (the “Liability Convention”), (iv) 1976 Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the “Registration Convention”), (v) 1979 Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Moon Agreement”), and (vi) 2020 Artemis Accords.

While multilateral approaches were once favored as a traditional mechanism to govern outer space, individual state action is on the rise, largely in part because of increased identification of resource potential—namely, the availability of precious minerals. Creation of an international agency or granting the United Nations authority over outer space resources is highly unlikely; and the creation of individual state agencies, while more tenable, does not address the international, cooperative governance required for the global commons. The third option thus prevails as the most likely scenario—states assert that each has the unilateral authority to extract resources. As state actors continue to embrace this strategy, other state actors have little choice but to follow the same approach, decreasing the likelihood of multilateral agreements. Thus, Parella’s framework offers a realistic governance overlay, allowing for oversight and changemaking without the niceties of formal international law.

III. The Necessity for Layered Approaches to Governance

International lawyers often express confidence in the rigor of international law to govern activities in space, but there are high tensions over the acceptance of multilateralism in an era of trending isolationism, exceptionalism, and non-interventionist stances. The political fluctuations of these policies may provide reassurance that multilateralism and international cooperation survive and endure. However, in those multilateral lulls and lows, there is an increased risk of private companies or isolationist States establishing extraction customs in outer space. Once established and ensconced, it becomes difficult to reject those practices and law often evolves around them.

The other major challenge is the physical and temporal distance of outer space regions to the Earth. Outer space resources—hidden resources—are far beyond the sight of Earth-bound observers, a physical manifestation of the saying, “out of sight, out of mind.” Control of outer space resources may still be manageable due to the restricted number of available commercial launch facilities; however, States make independent decisions with respect to launches and the number of space launch sites will only increase. Although commercial launch capabilities are now restricted to a few global centers, the privatization of commercial space transport will no doubt continue as entry costs decrease.

While international law remains an important foundation to govern space mining activities, it should not be the sole mechanism and, indeed, cannot. During a meeting of the SMU Subsurface Resources Research Cluster on April 29, 2024, Dr. Guillermo Garcia Sanchez described the energy legal process as a system of interconnected phases which only partly consist of the laws and contracts that govern exploration, discovery, development, production, and reclamation. These legal processes also include public and private law, in addition to industry customs and practices and other norms. The substantive laws and contracts operate in conjunction with the law of the resource situs—the law of the jurisdiction in which the resource is located. For example, offshore petroleum deposits are generally located in State waters (either in the Continental shelf or Exclusive Economic Zone), where the law of the State applies. In much of the rest of the world, the State, as sovereign, owns all mineral resources. However, States may invite or open resource development to firms outside the State, which then introduces international law to the transaction via the relationship between State and non-State firm(s). But where the resource is located beyond State boundaries, such as the high seas or outer space, international law also applies where recognized by consenting States—like those who are parties to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the Outer Space Treaty.

What happens then when space mining actors disregard the law, whether out of principle or for convenience? Yet, that firm belief in the absolute resolve of international law fails to consider the lessons of historical import. Space mining is just an old story in a new realm. During the Gold Rush of the late 1800s, immigrant miners from diverse lands, including England, Germany, Mexico, and South American nations, ventured to the American West to make their fortunes. Most all those ancestral miners came from countries where the sovereign owned all mineral resources and, critically, paid a royalty—the regalian right—to the State. The miners were not fond of such sovereign ownership and payment and had no intention of deliberately instituting the same in these new American mines. So, they borrowed those helpful traditions and customs of their native mining districts, such as free access and the extralateral right, while denying others, such as reporting production and provisioning a royalty. Subsequently, though the Western mineral deposits were primarily located on federal lands, the miners implemented their own desired customs, later codified by Congress into the General Mining Law of 1872—which still applies today.

Why then were these miners able to keep ownership of mines and the produced minerals? Arguably because of a governance vacuum. Though there were applicable laws on ownership of the land—“there was no law governing the transfer of rights to these minerals from public ownership to miners.” The miners took advantage of such regulatory absence.

IV. Governance Vacuums and the Parella Stakeholder Governance Model

Many believe the question of asteroid space mining to be settled—that States may not claim ownership of asteroids, but they can own what they extract. From a property perspective, I contest this distinction. I believe that the action of extraction of the part is by its nature an assertion of ownership of the whole. But while legal uncertainty increases the corporate firm’s transactional risk, it also increases the availability of first mover advantage and, arguably, the opportunity for innovation. High risk-high reward companies, like venture-capital backed space mining companies, may prefer operating in governance vacuums, where property right legal uncertainty abounds. Enter Parella’s stakeholder governance model. Parella’s model provides greater stability where a weak system of ownership exists and some stability where no framework exists.

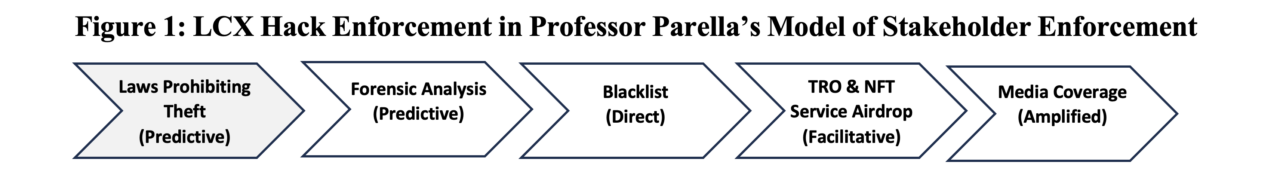

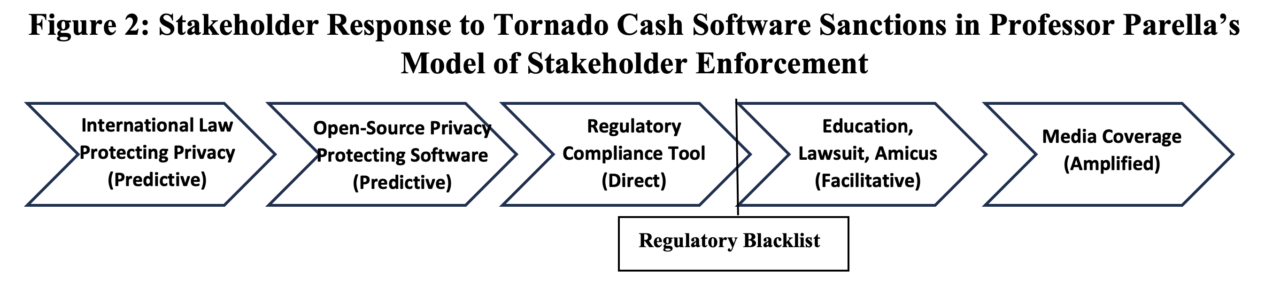

The main benefit of applying Parella’s model to space mining ventures is that it applies to both public and private companies. A central challenge in space extraction companies is a lack of transparency due to their often-private nature. Five of the largest companies—AstroForge (U.S.), Karman+ (U.S.), TransAstra (U.S.), Origin Space (China), and Asteroid Mining Company (U.K.) are all privately-held companies backed by venture capital. Before it was acquired by blockchain company, ConsenSys, Planetary Resources was a U.S. privately-held company, whose backers included billionaires Ross Perot Jr., then Google Chief Executive Officer Larry Page and Chairman Eric Schmidt, and former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. Co-Chairman John Whitehead. Neither corporation nor unincorporated publicly-traded company, these private companies have lesser built-in corporate accountability measures, like traditional shareholder governance. Further, there is not systematic financial reporting and mandatory disclosure of metrics like those on environmental, social, and governance goals; there may not be rigorous oversight for investors by federal agencies, such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Here is where Parella’s framework shines. Instead of relying on formal mechanisms to govern or shape company behavior, Parella looks to stakeholder management to pressure corporate actors to: “frequently align their behavior to conform to the values and expectations of a range of non-state actors—corporate stakeholders—such as consumers, employees, insurers, financial institutions, investors, industry organizations, and NGOs, among others.” She theorizes that “[t]hese stakeholders can address important gaps in the international legal order by offering incentives that nudge corporate actors toward compliance with international law.”

Moreover, Parella’s model is also practical, relying on enforcement by a variety of norm entrepreneurs and not just on a single State actor. Of particular interest to me is her meticulous, tabular identification of various stakeholder enforcement mechanisms, one of which is “monitoring.” Monitoring that is akin to an audit function will be crucial to space mining governance due the physical distance of potential mining sites from Earth observation—the main asteroid belt (between Mars and Jupiter) lies between 111.5 and 204.43 million miles from Earth. Because of the lack of physical visual site and a (cost-effective) method to visit the operation, the distant extraction community of miners, subcontractors, and other support tools/machines, can conduct operations without actual, observable oversight. Even the transmission of data to and from the mining site requires time, as a function of the distance. Although many missions and operations are conducted at great physical distances—for example, China’s recent unmanned mission to the far side of the Moon, the opportunity to disregard international law and custom or for malfeasance or misconduct increases without monitoring and the ability to audit.

Mining on planetary or lunar bodies is more complicated. As opposed to the Outer Space Treaty, there are fewer signatories to the Moon Agreement, and even fewer to the Artemis Accords. Notably, the major space exploring States, Russia and China, have signed neither. But whereas the potential for asteroid mining is great due to the millions of bodies surveyed, Martian and lunar mining sites are arguably more difficult—the property rights are more complicated. The difficulty arises with respect to the resource location. Minerals are not scattered among planetary crust in even fashion. They accumulate due to varying geologic and geomorphologic conditions and events over great periods of time. If one company establishes a mining location on Mars or the Moon, that location may preclude others from economically accessing the resource without disturbing the original company’s operations. Establishing, protecting, and defending mining operations could easily accelerate into risky, geopolitical situations. Parella’s model can diffuse future tensions by establishing cooperative frameworks, best practices in supply chain and operational management, and provide labeling of sourced minerals to help purchasers and end-users identify those minerals that are “conflict-free” or ESG compliant. The possibilities to apply Parella’s model are endless; and the potential to reduce threats is significant.

V. Conclusion

Natural resources are beset with antiquated legal doctrine. The lumbering laws governing mining arose from customs that primarily benefited the mining communities who formed them. Current congressional tensions hinder the passage of new natural resource legislation, though the Biden Administration has made good efforts to identify possible reforms to the 1872 General Mining Law. The incoming Trump Administration is likely to advance mining and space resource extraction, as it previously did during its first term. As always, science and technology has advanced far faster than the law and policy to govern them. And therein lies the power of Parella’s stakeholder management approach—it relies on an existing discipline that has had great success influencing corporate behaviors. International law is still the foundation of outer space activities. Applying stakeholder management principles, in addition to private contract and insurance, adds security to the business and mitigates the risk of failure.

[hr gap=”1″]