Feb 5, 2024 | Content, Online Scholarship, Perspectives

Michael Yip*

I. Introduction

In October 2023, two dozen countries gathered in Beijing to celebrate the Belt and Road Initiative’s (“BRI”) tenth anniversary. However, in ten years, little is understood about the bank loans that finance this initiative. On the one hand, the loans have been described as “debt traps” or “unsettling” projections of Chinese geo-economic power. On the other, the BRI has been characterized as an “international public good” or—in the words of the UAE’s Economy Minister—even “a gift to the world.” Naturally, both approaches—particularly when taken in isolation—are oversimplifications.

1. The Value of a Legal Perspective

Adopting a legal lens, however, would materially enrich our understanding of how BRI loans work in practical and empirical terms—enabling us to “look behind the headlines.” One aspect that has been overlooked is the “invisible law” that governs the loan agreement and disputes arising from the loan. Although this law—codified in the loan agreement’s choice of law, jurisdiction, and procedural law clauses—is an indispensable (albeit “boilerplate”) part of any banking contract nowadays, it has acquired an added significance in BRI loan documents. These clauses have become a venue in which different legal regimes—Chinese, English, New York, and others—project legal power and jostle with one another to shape China’s global development financing initiative (which itself goes on to project power and compete for prominence and acceptance in international affairs).

2. Key Findings

The data presented below shows that, based on the text of BRI loan agreements, Chinese law and dispute resolution mechanisms have been an increasingly popular choice. This indicates a characteristic of the BRI to induce “extraterritorial observance”: a shorthand term used by this article to describe the patterns and processes by which national laws are—as a matter of common and expected practice—observed by persons outside the country from which the laws originate. (In this case, Chinese law happens to be the object of extraterritorial observance, but history tells us that—because of processes such as globalization, migration, revolution, and colonialism—Soviet, Islamic, English, New York, and European Union laws have undergone a comparable experience.)

However, taking what the clauses in BRI loan agreements expressly say at face value would lose sight of the fact that they govern the loan in ways that cannot immediately be evident upon a cursory reading of the loan documentation. In other words, the governing laws have been—to a material extent—“invisible.” This is for three reasons. BRI loan agreements have often been kept secret; the depth, breadth, and content of the governing law have not been fully enunciated in the loan agreement; and some of the governing law may be found elsewhere in the laws of other countries.

3. Article Roadmap

This article will first explain the origins of the contest between legal regimes; describe the extraterritorial observance of Chinese law; and explain what makes the law governing BRI loans both consequential and invisible, before concluding thereafter.

These considerations are not merely academic. Indeed, when BRI projects go wrong, the “invisible law” determines how China and its borrowers will work out problems—on which, according to Christoph Nedopil, over a trillion dollars of taxpayers’ money, citizens’ livelihoods, and geo-economic power are staked.

II. Does a Competition Between Legal Regimes Exist?

At first glance, a competition between legal regimes may not appear to exist. After all, BRI loan agreements—and their clauses—constitute the final product of a negotiation and documentation process between the borrower and lender, supported by legal and financial advisers. Given this, any “competition” most visibly lies between the loan parties, rather than different legal regimes. This interpretation is supported by Ian Ivory and Cora Kang, who—in their book on the use of English law in BRI transactions—suggested that negotiations may be won or lost as part of a quid pro quo: “Where the question of using PRC law is sometimes raised, this is usually as a tool in negotiations and is traded for some other concession on the deal.”

However, the English judiciary and bar associations published a position paper titled: The Strength of English Law and the UK Jurisdiction. This paper advocated for the predictability of English law, claiming that it “respects the bargain struck by parties” and “will not imply, or introduce, terms into the parties’ bargain unless stringent conditions have been met.” Were disputes to arise, the paper also advocated for the UK’s “incorruptible judiciary” that was described as “structurally and practically independent.”

Those comments were made in 2017, attempting to provide reassurance and bolster confidence that—even after the UK’s departure from the European Union—English law was still suitable to govern cross-border contracts and English judges could still be trusted to adjudicate cases. Although the context of these comments, Brexit, is salient, they are just as applicable to the BRI—which at that point was still in its relative infancy (at four years old) and was, according to sentiment analysis conducted by Bruegel, better able to court interest in the West.

At the time, the judiciary’s and bar association’s comments also formed part of a broader set of advocacy messages by the UK state. They include 2016 remarks by the UK Advocate General for Scotland—a member of the executive branch—which emphasized the value of the UK’s law enforcement and legal services on the Belt and Road. In this light, both sets of comments can be cast as an example of one legal regime attempting to maintain its competitiveness in what Gilles Cuniberti called an “international market for contracts” and (by extension) for BRI loan agreements too. To those ends, there is no reason not to include initiatives such as the BRI as a plausible means to maintaining competitiveness in Cuniberti’s “market.”

By contrast, attempts by the Chinese legal regime to extend (rather than, in the English case, maintain) competitiveness have assumed a different form. Rather than an enticement-led approach (through position papers and other marketing campaigns), China’s approach has been directive-based and action-oriented. For example, the Opinions of the Supreme People’s Court on Further Providing Judicial Services and Guarantees by the People’s Courts for the Belt and Road Initiative stated that: “The people’s courts shall extend the influence of Chinese laws… and strengthen the understanding and trust of international businesses on Chinese laws.”

III. The Competition and “Extraterritorial Observance” in Numbers

To date, no attempt has been made to measure the contest between legal regimes to govern BRI loans. However, original analysis of AidData’s loan agreement repository undertaken by the author reveals the extent to which the BRI is inducing the extraterritorial observance of Chinese law.

1. Choice of Law Clauses

Choice of law clauses set out “the law that applies when interpreting the agreement and in determining any disputes regarding it.” A typical formulation of the clause can be found in the 2017 loan agreement signed between China and Sierra Leone that financed the upgrade and expansion of the Queen Elizabeth II Port, which reads as follows: “This Agreement and the rights and obligations of the parties hereunder shall, in all respects, be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of China.”

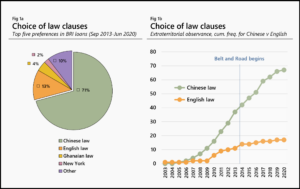

Fig. 1a shows the composition of choice of law clauses occurring in 48 loan agreements entered into by Chinese banks and overseas borrowers following the inception of the BRI. As shown, Chinese law has emerged as the dominant choice by 2020 (71%). However, this observation runs contrary to common practice of selecting a choice of law originating from a third country. This practice has been described by Philip Wood in a 2016 book commemorating the Loan Market Association’s twentieth anniversary as important “not because of familiarity or commercial orientation or any of those soft virtues, but rather to ensure that the loan obligations were insulated against changes to the loan agreement by a statute of the sovereign.” Philip Wood went on to indicate that such changes could include passing legislation to “forcibly” impose a debt moratorium, a debt rescheduling or a foreign exchange control of the loan currency. The primacy of Chinese choice of law clauses, however, most likely reflects Matthew Erie’s and Sida Liu’s view that China, as a “capital exporter, may occupy a dominant bargaining position vis-à-vis the host state.”

Fig. 1b shows the cumulative frequency of choice of law clauses in 101 Chinese-financed loans from 2003 to 2020. As shown, the adoption of Chinese choice of law clauses increased by 1.8 times from the BRI’s inception in 2013 onwards, whereas the same for English choice of law clauses grew by 1.5 times. This rate of adoption has meant that Chinese law clauses not only maintained but also enlarged their extraterritorial observance over time. English law clauses—the first-choice common law preference but nonetheless the second-choice overall—was unable to challenge Chinese law primacy, instead entering into a plateau that by 2020 had not yet been reversed.

2. Jurisdiction Clauses

Jurisdiction clauses “deal with the physical location of where a dispute will be heard, the type of institution (Court or Arbitration Tribunal) that will hear the dispute.” In practice, these clauses will often mimic choice of law clauses because, as Philip Wood noted in relation to syndicated loan agreements: “Once the governing law had been chosen, jurisdiction followed suit since the benefits of an external governing law might well be lost if the courts that enforced it were different, even though technically most courts could then, as now, apply foreign law.”

However, Chinese lending has produced noteworthy exceptions. In the pre-BRI era, an illustrative example is a RMB32 million loan provided by the Export-Import Bank of China (“China Eximbank”) to the Botswana Ministry of Finance and Development Planning for a housing project in the capital. In that loan agreement, the parties agreed upon an English governing law, but elected that disputes would be submitted to the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (“CIETAC”). In the AidData repository, other noteworthy hybrid combinations during the BRI era include a US$219 million loan provided by China Eximbank to the Philippine Department of Finance for the “Philippine National Railways South Long Haul Project.” In the loan agreement, Chinese governing law was chosen but the dispute resolution seat was the Singapore International Arbitration Centre.

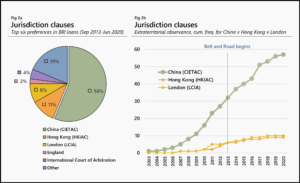

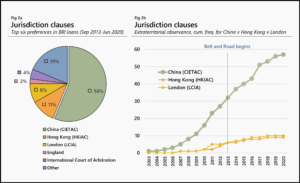

Fig. 2a shows the composition of jurisdiction clauses, which have aggregated variants such as different physical locations for the same arbitration tribunal or alternative venues if an urgent decision is required. However, as with the case of choice of law clauses and irrespective of the permutations on offer, the preference for the Chinese option—CIETAC—has been dominant (56%). In transactions for which a jurisdiction clause was ascertainable, the London Court of International Arbitration and Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre were in close contention, respectively competing for second and third place.

Fig. 2b shows the cumulative frequency of jurisdiction clauses. As shown, the adoption and extraterritorial observance of Chinese jurisdiction clauses grew by 1.8 times from the BRI’s inception in 2013 onwards. This growth rate mirrors the rate for Chinese choice of law clauses (discussed above), which indicates that the “hybrid combinations” discussed above were outliers rather than the norm. Meanwhile, Hong Kong jurisdiction clauses grew by 1.5 times and those of London grew by 1.7 times.

3. Procedural Law Clauses

Procedural law clauses stipulate the rules by which the dispute resolution seat will administer the adjudication of the dispute. In practice, these clauses will often mimic jurisdiction clauses because—where national courts have been nominated—compliance with their procedures tends to be mandatory. For example, litigants in Chinese and English courts must follow the civil procedure rules for each country in order for their case to be tried. However, the rules of arbitration tribunals give an established right to choose and/or modify the procedural law governing their arbitration.

The “right to choice” in a BRI arbitration context is demonstrated by an US$85 million loan provided in 2010 by the CITIC Bank and China Construction Bank to the Argentinian Ministry of Economy and Public Finance to finance construction of and supplies to the Lina-A Metro in Buenos Aires. In that loan agreement, the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre was given jurisdiction, but the procedural law chosen by the parties was that of the U.N. Commission on International Trade Law.

What both transactions show is that there is substantial flexibility in the contractual terms governing procedural law – but only where arbitration is concerned. Furthermore, no loan agreements substituted the procedural law of one national arbitration tribunal for those of another national arbitration tribunal. No transaction, for example, gave jurisdiction to the London Court of International Arbitration but chose the procedural law of a Chinese arbitration tribunal. Instead, where substitutions have occurred, they have swapped the procedural law of a national tribunal with multilateral procedural law formulated by an international organization.

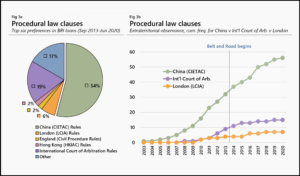

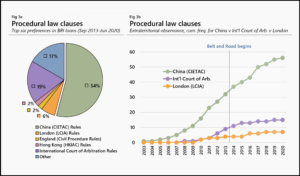

Fig. 3a shows the composition of procedural law clauses. As with the choice of law and jurisdiction clauses, the preference for the Chinese option—the rules of CIETAC—has been dominant (54%). Fig. 3b shows the cumulative frequency of procedural law clauses. As shown, the adoption and extraterritorial observance of Chinese procedural law clauses grew by 1.8 times from the BRI’s inception in 2013 onwards.

IV. The Laws are Consequential but Operate “Invisibly”

1. On Consequentiality

The laws described above are consequential in three ways. First, they serve as a gateway for troubled transactions and parties in dispute to seek support from judges and arbitrators on contested points of law. As the BRI matures and moves into its second decade, loan transactions will enter rougher waters and the three clauses discussed will come to the fore—especially as China is pushing to play a more active dispute resolution role in the international legal order through the China International Commercial Court. Doing so enables China to place less reliance on resolving problems through ad-hoc diplomatic channels, as was recently seen when Zambia restructured US$4.1 billion of debt owed to China.

Second, the clauses serve as conduits for extraterritorial observance and channel the legal power that countries exert on each other. The impact of these clauses is at their most pervasive when individual jurisdictions (such as England, New York and—increasingly—China) shape the international legal order to induce others from overseas to voluntarily observe their laws or, alternatively, their approach to the practice of law. For instance, the English jurisdiction, through its Loan Market Association, promulgates standard-form loan agreements—that have often been English law-governed – to lenders and borrowers of all origins. So, in a similar vein, could a standard-form template for BRI loans materialize one day? Possibly. In their landmark work How China Lends, Anna Gelpen et. al. have already identified emergent patterns in clauses covering events of default, confidentiality duties and repayment mechanisms across 100 Chinese loan agreements. However, notwithstanding that those patterns are—in their 2024 form—unlikely to constitute a self-standing BRI template, templates materialize slowly. By way of illustration, Philip Wood recollected that the first syndicated loan agreement governed by English law may have drafted in 1968. Since then, it has accumulated nearly 60 years of updates and modifications. Building a template takes time. Let us wait and see.

Third, the clauses—and their propensity to nominate one choice of law or jurisdiction to the exclusion of others—drive and divert significant amounts of business for law firms. Over a longer time horizon, the BRI may go on to bring many millions of dollars of business to the law firms with the capability to advise on Chinese law matters. These law firms include both “home-grown” Chinese firms as well as international outfits that have entered into joint ventures with Chinese partners.

2. On “Invisibility”

Yet, the law governing BRI loan agreements operates invisibly and in ways that a mere examination of the documents would not reveal. It does so in three ways. First, as Anna Gelpern et. al. have discovered, BRI loan agreements contain “far-reaching” confidentiality clauses that restrict the borrower’s ability to disclose information about the loan. (This differs with commercial practice, in which it is typically lenders who have been prevented from disclosing confidential information, primarily to uphold borrower privacy.)

Second, the content of the law and the situation-specific rules governing BRI agreements will not be fully enunciated in the three clauses. The clauses cannot (and simply do not have the space to) articulate the legal rule for a complete universe of legal problems that may arise in relation to the loan. Accordingly, at best, the clauses serve as signposts to very large bodies of law, which in turn require further expertise to understand and apply. (Furthermore, the varying levels of comprehensiveness and depth of codification within the Chinese, English and other legal systems will not only add further complexity to ascertaining the proper legal rule, but also subject that ascertainment to interpretation and/or modification by judges.) In this sense, the governing law of a BRI loan may not only be invisible to the reader of loan agreement, but also uncertain.

Third, although parties to a BRI loan generally have the autonomy to select their own choice of law, this may be (or attempt to be) overridden by a foreign mandatory law that is “unseen” and on which the text of the loan agreement was silent. For example, in the case of loans governed by Chinese law and involving a private borrower, plausible mandatory laws—as noted in 2022 by Philip Wood—most likely include the borrower country’s insolvency laws. These could conflict with a Chinese governing law expressly chosen by the parties if the borrower entity became insolvent and claims on borrower assets were made by creditors. (The same, however, would not apply to sovereign borrowers who would instead be caught between an expressly-chosen Chinese governing law and soft international obligations such as Paris Club rules.) Elsewhere, a similar (albeit more indirect) example arises in the field of environmental law. A borrower country’s planning and environmental laws would apply to government licences which, in turn, would be required to develop a site into a project and which would typically be listed as part of conditions precedent to the loan being drawn down by the borrower. Finally, with respect to loans governed by a non-Chinese law, plausible sources of mandatory Chinese law include the “social public interest” exception to party autonomy. Given that mandatory laws of any jurisdiction present a “hidden minefield” to BRI parties, their advisers would do well to acquaint themselves with Chinese and non-Chinese approaches to conflict of laws.

V. Conclusion

There is a contest between legal regimes to be attractive and to—wherever and whenever possible—be taken up and observed by international commercial parties. This contest has long predated the BRI. However, the loan agreements underpinning China’s initiative serve as a new arena for contestation in which a new alternative—China’s laws and dispute resolution mechanisms—show early signs of taking primacy over more established alternatives from North America and Europe. The consequences of this “extraterritorial observance” are significant: a legal regime’s entrenchment and prominence in transactions tends to sustain itself, by setting the norm for future transactions and/or by governing the forthcoming disputes. In turn, extraterritorial observance precipitates more business activity for its lawyers. For practitioners, this can indeed be a virtuous cycle.

However, the laws governing BRI loans operate invisibly. As has been the case with any complicated transaction pre-dating the BRI, it may be difficult to ascertain which loans are governed by which laws; which doctrines of expressly-chosen laws apply; and how local laws may mandatorily override the choice of the parties. One day, these laws could be called upon to determine the outcome of the very first BRI banking dispute. Such a dispute will plausibly place billions of dollars at risk; materially shape the direction of BRI lending practices; and bring about the collision of law against another. For these reasons, how invisible laws govern bank loans on the “Belt and Road” deserve an ever-watchful eye.

*Michael Yip is a Research Associate in “China, Law and Development” at the University of Oxford, where he is also the Research Cluster Lead for legal services. Previously, he was a British civil servant and worked at the World Bank’s Legal Vice Presidency, specialising in export and infrastructure finance. Michael also holds an LLM as a Yenching Scholar from Peking University in China.

Cover image credit

Dec 19, 2023 | Online Scholarship, Perspectives

Introduction

The diplomatic relationship between the Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic is further complicated by the Massacre River affair. Tensions between the two countries, which share the island of Hispaniola, have never been so high in recent decades. The subject of dispute is the construction of an irrigation canal fed by the Massacre River, which the two countries share. Plunged into a deepening humanitarian crisis and plagued by insecurity and armed gang violence, Haitians see the construction of the irrigation canal as a matter of survival, food sovereignty, or a kind of last gasp. However, the Dominican authorities argue that the canal would divert water from the Massacre River, violating the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929, concluded by the two countries. This situation creates tensions between the two nations and highlights the issues and challenges relating to the management and use of water from the Massacre River. At a time when this dispute is causing major friction between the two peoples, it is more crucial than ever for the two states to strengthen their diplomatic relations if they are to avoid stirring up dark memories of the past.

I. The Facts

The Massacre River is a small coastal river that flows into the Atlantic Ocean and is a border waterway between the Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In August 2018, Haitian President Jovenel Moïse launched the construction of an irrigation canal on the Massacre River. Water from the Massacre River was to irrigate 3,000 hectares of highly fertile land in the Maribahoux plain in northeastern Haiti, to alleviate the misery of the inhabitants. The project drew protests from the Dominican Government. On April 26, 2021, several Dominican soldiers from the Cuerpo Especializado en Seguridad Fronteriza Terrestre (CESFRONT) intimidated the Haitian workers. On May 27, 2021, with a view to finding a diplomatic solution, the two States convened a meeting of the bilateral Joint Commission at the Ministry of External Relations of the Dominican Republic. The Commission’s technical secretaries signed a joint declaration recognizing that the proposed irrigation canal would not alter the natural course of the waters. Since the assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse in July 2021, the project has slowed down, but Haitian farmers, supported by several civil society organizations, started digging again in August 2023, hoping that water would one day reach their cultivation fields. Today, this irrigation canal is the subject of heated controversy between the two countries. While the Haitian Government is open to dialogue to find a favorable outcome, on Friday, September 15, 2023, Dominican President Luis Abinader decided to close all borders. In a press release issued on the same day, the Haitian government declared that the Maribahoux plain irrigation project would continue. At a time when the Haitian people are facing an acute social, humanitarian, and political crisis, the management of this conflict is of crucial importance. To better understand the current dispute over the Massacre River between the Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, it is essential to bear in mind the long-standing and still-latent conflict over this international waterway.

II. The History

The history of the border between Haiti and the Dominican Republic is essentially one of tensions and exactions. This border was to change with conquest, reunification, independence, and tyranny. The Massacre River was the scene of fierce rivalry between the French, who felt the river belonged to the western part of the island of Saint-Domingue, and the Spanish, who wanted the river to separate their lands from those of the French on the mountainous side. The river’s name reflected the tensions between the two parts of the island. It was called the Massacre River because the two peoples had often come to blows on its banks. The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 already mentioned the Massacre River. Some historians claim that the river’s name evokes the incessant skirmishes between French buccaneers and Spanish soldiers on its banks, while others maintain that it is a reference to the memory of one of the many wars of extermination that wiped out the indigenous Arawak population. Whichever hypothesis is adopted, it should be noted that the island seemed destined for a tragic confrontation, an anticipatory sign of the violence that was to accompany the birth of Haiti and its relations with the neighboring Republic. It was the Treaty of Aranjuez (1777) that established this river as the boundary of sovereignty between France and Spain.

III. Corpus Juris

In the context of bilateral relations between the Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the law applicable to international waters is corpus juris dating from the mid-twentieth century. The law governing international watercourses has been codified in legal instruments such as the Treaty on the Delimitation of the Frontier between the Dominican Republic and the Republic of Haiti of January 21, 1929, the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929, the Boundary Agreement between the Dominican Republic and the Republic of Haiti of February 27, 1935, and the Additional Protocol to the Treaty of January 21, 1929, Regarding the Delimitation of the Frontier Between the Dominican Republic and the Republic of Haiti of March 9, 1936 (“Additional Protocol”).

The most important legal instrument remains the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929, which views international waters as shared natural resources and contains some of the principles and rules that would later be elaborated in broader forums such as the United Nations. The Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses of May 21, 1997 (“United Nations Convention”) essentially regulates international watercourses, which are defined as “watercourse[s], parts of which are situated in different States.”

The Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929 codifies the use of the waters of the rivers Libón and Artibonite, as recalled in Article 6 of the Additional Protocol: “The waters of the rivers Libón and Artibonite belong equally to the two riparian States, and use thereof shall be subject to the provisions of Article 10 of the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration signed in the city of Santo Domingo . . . on February 20th, 1929.”

Article 10 of the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929 enshrines the right of either state “to make just and equitable use, within the limits of their respective territories, of the said rivers and streams for the irrigation of the land or for other agricultural and industrial purposes.”

In other words, this Treaty prefigures the principle of equitable and reasonable sharing found in Article 5 of the United Nations Convention, which emphasizes that “Watercourse States shall in their respective territories utilize an international watercourse in an equitable and reasonable manner . . . [and] participate in the use, development and protection of an international watercourse in an equitable and reasonable manner.”

Moreover, Article 10 of the Treaty also lays down the obligation not to cause significant damage: “[T]he two High Contracting Parties undertake not to carry out or be a party to any constructional work calculated to change their natural course or to affect the water derived from their sources.” A similar formulation of this principle can be found in Article 7 of the United Nations Convention, which establishes the obligation not to cause significant damage to other watercourse States.

The question of equitable and reasonable use can be assessed in light of the criteria set out in Article 6 of the United Nations Convention. Although the Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic are not parties to this Convention, it would be logically and legally possible to interpret the provisions of the Treaty in accordance with the principles of international law, considering, for example: “Geographic, hydrographic, hydrological, climatic, ecological and other factors of a natural character; The social and economic needs of the watercourse States concerned; The population dependent on the watercourse in each watercourse State; The effects of the use or uses of the watercourses in one watercourse State on other watercourse States . . . .”

In the case relating to the territorial jurisdiction of the International Commission of the River Oder (1929), the Permanent Court of International Justice interpreted the principles of equitable, reasonable, and non-damaging use of the watercourse through the notion of community of interests uniting riparian States around an international watercourse:

“But when consideration is given to the manner in which States have regarded the concrete situations arising out of the fact that a single waterway traverses or separates the territory of more than one State, and the possibility of fulfilling the requirements of justice and the considerations of utility which this fact places in relief, it is at once seen that a solution of the problem has been sought not in the idea of a right of passage in favour of upstream States, but in that of a community of interest of riparian States. This community of interest in a navigable river becomes the basis of a common legal right, the essential features of which are the perfect equality of all riparian States in the user of the whole course of the river and the exclusion of any preferential privilege of any one riparian State in relation to the others”.

Equitable and reasonable use also presupposes consultation in a spirit of cooperation. For example, a state cannot decide unilaterally on the allocation of a watercourse if other riparian states want to see their own interests considered. The obligation to notify and consult helps to resolve tensions and controversies, as recalled by the International Court of Justice in the Pulp Mills case (2010). Thus, the obligation to notify is essential in the process, and it should lead the parties to work together to assess the risks of the project and negotiate any modifications likely to eliminate them or minimize their effects. The principle of fair and reasonable use can therefore also be applied by prior notification of the project.

IV. Discussion

In the Massacre River affair, the Haitian Government undertook the construction of an irrigation canal in 2018 to water the Maribahoux plain. This is the first project launched by the Haitian Government on the Massacre River, while the Dominican Government has already built several aqueducts and irrigation canals. Opposing the canal construction project, the Dominican government argued that the project constituted a detour of the river and a threat to the environment. The two States consulted each other to assess the project’s risks. In May 2021, they adopted a Joint Declaration stating that, on the basis of the information provided by the representatives of the Republic of Haiti and in the spirit of understanding and exchange of information in accordance with what is stipulated in the Treaty, the project being carried out on the Massacre River for the abstraction of water does not constitute a detour of the watercourse. It was therefore clear from the facts that the project undertaken by the Haitian government was not likely to divert the watercourse and reduce the flow of water and did not undermine the protection of the environment and the promotion of sustainable development.

The Joint Declaration was based on a study conducted by the Dominican National Institute of Hydraulic Resources (INDRHI) in 2021. This study recognized that the project would require a flow between 1.5 and 3 cubic meters per second, which represents 20.33% of the average annual flow of the Massacre River. Thus, the flow would still be below the extractions made on the Dominican side. Finally, the researchers added that two-thirds of the Dominican agricultural land irrigated with the Massacre River’s water is located upstream of the canal under construction.

Nevertheless, we must acknowledge that Haitian farmers continued in August 2023 in the absence of Haitian government control. If the spontaneous initiative of the farmers to pursue the irrigation project is to be understood from the point of view of their urgent economic and social needs, the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929, confers only on states, and not on the citizens themselves, the right to undertake construction work on watercourses. It is therefore incumbent upon the current government to regain control of the project in accordance with the standards established by bilateral treaties and international legal instruments. In a press release dated September 15, 2023, the Haitian Government declared its intention to take all measures to ensure that irrigation of the Maribahoux plain is carried out in accordance with scientific standards, under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Rural Development and of the Environment. For the time being, however, the irrigation project is being carried out according to the sovereignty of a people completely neglected by their government.

Dominican President Luis Abinader’s decision to close his borders with the Republic of Haiti would contravene the Joint Declaration of May 27, 2021, which paved the way for coordinated institutional management, and the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration. In the context of this dispute, it would perhaps be more interesting to envisage a peaceful and amicable outcome, by considering “all relevant information on the water table, hydrological studies, environmental impacts and other information outlined in the May 2021 Joint Statement.” Furthermore, in the spirit of joint management of shared water resources, the two parties could draw up a technical protocol for the coordinated management of transboundary watersheds. Finally, the Organization of American States could play an important role in facilitating an amicable settlement through mediation. Failing agreement, recourse to international arbitration remains the most appropriate method for resolving this dispute.

The Dominican Republic’s decision also appears to disregard the first paragraph of Article 3 of the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration of February 20, 1929, which underlines the obligation to resort to investigation and conciliation procedures:

“The High Contracting Parties undertake to submit to arbitration all disputes of an international character which may arise between them as a result of one of the Parties claiming a right as against the other, under the terms of a treaty or otherwise, when it has not been possible to settle this claim by diplomacy and when the claim is of a legal nature inasmuch as it is capable of decision according to the principles of law.”

This clause of consent to international arbitration obliges each party to initiate prior amicable and diplomatic attempts to settle a dispute. If the attempt at diplomatic resolution fails, the disputing party may bring the dispute before an arbitrator or an arbitration tribunal, depending on the agreement of the parties. By failing to attempt a diplomatic or arbitral resolution, President Luis Abinader has thus strayed from the path of peaceful resolution mapped out by the Treaty.

Article 5 of the same Treaty sets out the way the arbitral tribunal is to be constituted:

“The arbitrator or tribunal to decide the controversy shall be appointed by agreement between the Parties. Failing agreement, the following procedure shall be observed: each Party shall appoint two arbitrators, only one of whom may be a national of the said Party or chosen from among the persons nominated by the said Party as members of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague; the other member may be of any other American nationality. These arbitrators will, in their turn, choose a fifth arbitrator, who shall be the President of the tribunal.”

While the Dominican Government is choosing the worst option, preferring a justice of force based on reprisals instead of relying on the strength of justice, it could simply have chosen the amicable option, and in the event of its failure, the arbitration procedure. It is high time we remembered that gunboat diplomacy is no longer fashionable.

The Dominican Government has already acknowledged that the Haitian project is an irrigation project that in no way endangers downstream ecosystems. The onus is now on the Dominican Government to demonstrate that the current intake on the Massacre River constitutes a damaging and inequitable use of water resources and is detrimental to the environment.

No state can guarantee itself exclusive use of shared water resources. The Republic of Haiti is therefore entitled to pursue the Maribahoux plain irrigation project. However, it must be stressed that this must be done in accordance with technical and scientific requirements, and in compliance with environmental standards.

In the midst of this major controversy, and especially in the midst of the climate crisis, the Haitian government should take the opportunity to take a step to the side by demanding that the Dominican Republic provide precise information on the various works it has undertaken on the Massacre River, with a view to determining whether the Dominican authorities are not significantly reducing the flow of water that Haitians could use downstream.

V. Perspectives

To re-establish a healthy and lasting diplomatic relationship between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the poetics of dialogue are more than necessary. For the future of these two neighboring brothers, the methods of peaceful settlement of disputes must remain essential tools. Diplomacy is the key to peaceful coexistence on the island. It is important to emphasize this in the context of intense tension between the two nations, where Haitians living in the Dominican Republic are sometimes subjected to inhumane, undignified, and degrading treatment.

The Massacre River case teaches both neighboring countries that it is time to take the initiative for a specific river treaty project, particularly in a context where access to and management of water resources pose crucial environmental and social challenges. This would be even more interesting given that the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration still in force today is over a hundred years old. But things have changed since then. In addition to the issues of irrigation production for agricultural purposes and use for industrial purposes set out in Article 10 of the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration, other issues such as energy production, access to fresh water for human consumption, environmental protection, and preservation of cultural heritage are gaining in importance. Beyond the Treaty’s principles of equitable and reasonable use, the obligation not to cause significant harm, and the principle of equality of use, new approaches are emerging in international law to meet essential human needs and new environmental challenges. This calls for a watercourse treaty adapted to recent social, environmental, and climatic developments, which will be an important step forward in the management of watercourses, based on a global vision. This issue is even more relevant given that the Libón River – an international waterway originating in Haiti – could also in the future be the subject of intense tensions between the two countries in the context of mining operations in the border zone by two Canadian companies, Unigold and Barrick Gold.

As soon as it affects their diplomatic and trade relations, the Massacre River dispute benefits neither Haiti nor the Dominican Republic. To reach a peaceful settlement of this dispute, it is more than necessary to return to the negotiating table in accordance with their treaty obligations. Both parties can count on the Organization of American States (OAS), which has a proven track record in mediation in the Central American region. To facilitate the peaceful resolution of the dispute, the two governments must communicate all relevant information and research data available concerning the water table, the hydrological regime and potential environmental impacts. If the attempt at diplomatic resolution fails, the parties may then submit their dispute to international arbitration. Moreover, to prevent or manage their potential conflicts in the future, the two states need to rethink the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Arbitration, which is already almost a century old. The Republic of Haiti and the Dominican Republic may consider negotiating a forward-looking treaty accounting for new social, humanitarian, climatic, and environmental challenges. This initiative may prove important for a better coexistence of the two neighboring brothers.

*Milcar Jeff Dorce holds a PhD in Public Law from the University of Bordeaux, Center for European and International Research and Documentation. He specializes in international investment law and arbitration.

Cover image credit

Dec 8, 2023 | Online Scholarship, Perspectives

Manasa Venkatachalam*

Introduction

With the swelling of nationalism globally, the definition of national identities is becoming increasingly restrictive. This phenomenon is extremely evident in India, where the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) expressly relies on national origin and religion as factors to determine eligibility for citizenship. In this climate of individualistic, national identities, it is important to evaluate how this sense of belonging ties into legal frameworks governing identity, and in particular, definitions of citizenship. Given the involvement of ethnic, national, and religious factors that have become increasingly evident in the granting of citizenship in several parts of the world, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (“ICERD”) becomes a relevant tool to assess such issues from an international legal perspective. This article utilizes the ICERD to examine this leading question: how far can states go in creating criteria to exclude those from citizenship based on ethnic or religious grounds?

Scholars belonging to the Third World Approaches to International Law school often point out how citizenship was created to sustain a colonial and imperial order, and thus, citizenship laws are aimed at excluding “backward” peoples who were viewed as incapable of possessing property and exercising rationality (see, e.g., Bhandar, p. 35; Shahid & Turner, p. 7). The historical exclusion of indigenous communities, women, and people of color from the privilege of citizenship illustrates how citizenship status is used as a tool of “othering” (Edwards). This practice continues in the post-colonial era despite global developments like the ICERD.

The proposal to codify an international prohibition on racial discrimination emerged from the recently independent Pan-Africanist segment of the United Nations. Concerned by the othering and racist discrimination inherent in colonial imperialism, Global South states engaged in forceful multilateral human rights diplomacy to build support for an international prohibition on racial discrimination (see Schabas, p. 248-52). Their efforts resulted in the U.N. General Assembly’s approval of the ICERD in 1965 (Preamble, para. 4; Keane & Waughray, p. 4; Boyle & Baldaccini, who point out how the ICERD painted racism as being “solely about the consequences of Western imperialism”). Even the International Court of Justice (para. 86) has observed that the Convention was drafted “against the backdrop of the 1960s decolonization movement.”

In many ways, the ICERD represents law-making by and for the “Third World.” The Convention’s history makes it an interesting tool to use to examine issues of racial discrimination in the Global South. Still, the ICERD is not without its issues. One significant problem is that Article 1(3) of the ICERD excludes review of domestic nationality laws from the scope of its protection. The International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) has subsequently touched upon the ambit of the exceptions to the prohibition of racial discrimination regarding nationality in its interpretation of the term “national origin.” However, the ICJ confined its analysis to the ICERD and did not consider whether the prohibition on racial discrimination has independent customary character. The International Law Commission’s (“ILC”) recent work (p. 16) on documenting jus cogens norms has introduced a new factor to consider: whether the prohibition of racial discrimination is a peremptory norm. Since peremptory norms are non-derogable,[2] if the prohibition on racial discrimination has peremptory status, all exceptions to this prohibition become irrelevant. This makes the applicable law a lot simpler and the exceptions to the prohibition on racial discrimination in Articles 1(2) and 1(3) of the ICERD inoperative. Using India’s 2019 Citizenship (Amendment) Act (“CAA”) as an example, this article attempts to resolve the conflict between the ICERD’s prohibition of racial discrimination and the carve-out provided under ICERD Article 1(3), which exempts legal provisions concerning nationality from the scope of ICERD’s protection. In doing so, this article purposely distances itself from the explanations offered by the ICJ in Qatar v. UAE, choosing to instead focus on a different approach than the judgment: the possible peremptory nature of the prohibition of racial discrimination.

I. The ICERD and Nationality

The ICERD is one of the most widely ratified human rights treaties in the world. It has 182 states parties. This makes it a powerful tool to regulate discrimination in citizenship laws and practices (see Hoornick, p. 224). Article 1 of the ICERD prohibits racial discrimination, and Article 5(d)(iii) extends this prohibition to guarantee the enjoyment of the right to nationality regardless of race, color, or national or ethnic origin. However, there are certain exceptions to this prohibition that weaken the ICERD as a tool to combat discriminatory citizenship practices. Mainly, Article 1(3) cabins the ICERD’s scope to exclude review of legal provisions of states parties concerning nationality, citizenship, or naturalization as long as such laws do not discriminate against any specific nationality. Thus, the ICERD presents contradictory positions on the issue of discrimination in the grant and denial of citizenship.

Article 1(3), ICERD: Gaps and Relevance

Paragraphs (2) and (3) of Article 1 detail exceptions revolving around citizenship to the prohibition on racial discrimination in Article 1. Article 1(3) of the ICERD reads: “Nothing in this Convention may be interpreted as affecting in any way the legal provisions of States Parties concerning nationality, citizenship or naturalization, provided that such provisions do not discriminate against any particular nationality.” Article 1(2) excludes the application of the ICERD from “distinctions, exclusions, restrictions or preferences made by a State Party to this Convention between citizens and non-citizens.” While the exception provided under Article 1(2) featured more prominently in Qatar v. UAE (see para. 83), Article 1(3) has not received such jurisprudential attention. This could be an indication of states’ and courts’ attitudes towards the sovereign sacredness attached to laws governing citizenship, as emphasized in the ICJ’s Nottebohm judgement.[2] The question that has gone unanswered owing to this lack of discussion is whether grounds other than discrimination against a particular nationality can be used to maneuver around ICERD Article 1(3).

Before delving into an analysis of the ICERD, it is important to highlight the practical importance of this inquiry. The current government in India is led by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. The party’s representatives, specifically the Union Home Minister, have made several statements indicating their anti-Muslim sentiment and how the CAA and the impending National Register of Citizens (“NRC”) are coordinated policies to remove Muslims from the country.[3] Consequently, the next section will highlight the disparate grant of citizenship in India and the international legal consequences of these policies.

II. India, the CAA, and the NRC

The CAA amends the Indian Citizenship Act of 1955 to make specific classes of illegal migrants eligible for citizenship. Prior to this amendment, any person who satisfied the definition of an illegal migrant would not be eligible for Indian citizenship, and neither would their children (see s. 2(b) of the 1955 Act). However, the CAA establishes that if a person (1) belongs to the Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian community, (2) is from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, or Pakistan, or (3) entered India on or before 31st December 2014, such a person is now eligible for Indian citizenship.

The Union Government also plans on introducing a NRC for the entirety of the nation. The NRC would contain the names of all “genuine” Indian citizens, requiring persons to submit evidence to prove citizenship per the criteria in the 1955 Act (see Arts. 3 to 6). A similar system has been implemented in the Indian state of Assam. While this policy has not yet been enacted on the national level, the intention of the CAA and the NRC, as the Home Minister noted, is to “weed out” immigrants that the government deems illegal.

Data from the State of Assam illustrates the effect a nationwide NRC and CAA could have. In 2017, the first draft of the NRC was published for Assam. It excluded 19 million people out of 32.9 million applicants for citizenship. The final NRC for Assam was published in 2019 and excludes 1.9 million people from the list, deeming them all not citizens of India. While citizenship in Assam has always been regulated slightly differently ever since the influx of migrants and refugees from Bangladesh in the 1970s, this data offers insight into the impact that the CAA and NRC could have on the rest of the nation.

The Indian CAA and Discrimination Under ICERD Article 1(1)

In short, the CAA does distinguish and exclude individuals based on identities protected by the ICERD, nullifying basic human rights guaranteed to such persons.[4] It excludes any persons other than those from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh from the benefits of citizenship, which can be argued to amount to discrimination based on national origin.[5] As of April 2023, India hosts over 213,000 refugees and asylum seekers, most hailing from Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, China or Myanmar (UNHRC 2022, p. 9). Around 92,000 of these people originated in Sri Lanka, 72,291 from Tibet, and 30,308 from Myanmar (UNHRC 2023), and these are only those registered with the government (UNHRC 2022, p. 9). On the other hand, 14,466 refugees and asylum-seekers are from Afghanistan (UNHRC 2023), and even fewer are from Bangladesh and Pakistan. The law also clearly distinguishes between persons based on religion, as it only covers persons from Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian communities.

Additionally, the CAA violates several human rights, including the right to nationality and the right against statelessness. The right to a nationality, though disputed, seems to have entered today’s body of customary international law. Making its earliest appearance in Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it has been transposed in varying forms into six of the nine core human rights treaties,[6] all of which have widespread ratification, strongly indicating state practice and opinio juris.[7]

The deprivation of the right to nationality has far-reaching consequences. Nationality is the “right to have rights.” Though human rights are inherent, citizenship is often the right that enables the enforcement of all rights; it is the connection between the State and its citizens that ensures the former’s protection of the latter (see Kesby). The deprivation of the right to nationality, consequently, is a deprivation of the vehicle for access to fundamental rights and protection under domestic law.

And, of course, nationality and statelessness are intimately linked. Dubbed a corollary of the right to a nationality (ILC, p. 27), the obligation to prevent and reduce statelessness is now widely considered customary (Case of the Girls Yean and Bosico, paras. 139-141; Blackman, p. 1183; Adjami & Harrington, pp. 102-3 for an in-depth explanation).[8] Statelessness, simply put, is the absence of nationality (1954 Convention, Art.1; Rütte, p. 242). For this reason, the duty to prevent statelessness has been described as a negative right arising from the right to a nationality (Blackman, p. 1176). When combined with the norm of equal and effective protection of the law (Juridical Condition and Rights of Undocumented Migrant, para. 101; UDHR, Art. 1; ICCPR, Art. 26; ICESCR, Arts. 3, 7; CRC, Art. 2; CEDAW, Art. 1), states must abstain from creating discriminatory mechanisms to grant citizenship (Case of the Girls Yean and Bosico, para. 141).

The CAA was enacted with the purpose of providing citizenship to a select few based on national origin and religion and, consequently, depriving the rest of the same. Additionally, irrespective of its purpose, the CAA certainly impeded the right to nationality of persons of national origin in countries other than the three mentioned. These distinctions imply that the CAA impairs the enjoyment of human rights on an equal footing, engaging the CERD’s definition of racial discrimination.

III. Article 1(3) ICERD: A Free Pass for India?

On a purely textual analysis, Article 1(3) of the ICERD would exclude the CAA from the ICERD’s protections. India’s law clearly covers issues of nationality and citizenship, and it does not distinguish against any nationality per se. (It does distinguish on national origin, but national origin has generally been regarded as different than nationality (ICJ, Qatar v. UAE, para. 105)).

A different way to look at the issue is to assess whether the prohibition on racial discrimination has peremptory status. The ICJ declined to take this approach in Qatar v. UAE. But the obligation to not undertake racial discrimination has been deemed erga omnes by the ICJ (see dicta in Barcelona Traction (para. 34)), and the ILC deemed it a jus cogens norm in 2022 (see Annex (e)). Treaty provisions that conflict with peremptory norms are non-derogable and void per customary treaty interpretation rules.[9] Thus, any exception to the prohibition of racial discrimination would be nullified, including Articles 1(2) and (3) of the ICERD. Unfortunately, the ICJ did not touch upon this in its judgment in UAE v. Qatar. Had it, would the outcome have been different?

An obvious reason as to why the ICJ did not venture into this territory is the severity of the approach. Recognizing ICERD’s prohibition on racial discrimination as reflective of customary international law would deal a considerable blow to the sovereign discretion of States in matters of nationality. Courts are legitimate when they are perceived as having the authority to make decisions, and the ICJ is not exempt from this idea. Legitimacy capital is thus linked to authority: when international courts act in a manner that could be perceived as exceeding the scope of authority granted to them, they lose authority (see Grossman et al., p. 5). Consequently, a decision from the ICJ that would use jus cogens as a means to override significant treaty provisions representing the sovereign will of States is highly unlikely, given the shockwaves it would generate with respect to its legitimacy. That being said, such a decision would still be a legally acceptable and effective means to expand the prohibition on racial discrimination.

Conclusion

Public international law has long recognized the State’s sovereign discretion in dictating terms for membership (Donner, p. 17). A permanent population is necessary for statehood; thus, the ability to control the membership of this population is a vital aspect of sovereignty (Mantu, p. 25). However, the focus on individual human rights is eroding this sovereignty-backed discretion. One tool contributing to this erosion has been the prohibition of racial discrimination.

Still, the untapped potential of the ICERD to evaluate selective nationality laws is striking. Selective citizenship laws deprive persons of vital fundamental rights, but remain under the international legal radar. The ICERD must be used to the fullest as a counter to such laws. With the ICERD’s growing usage in international litigation, the time for a challenge to discriminatory laws like India’s CAA may be ripe.

*Manasa Venkatachalam completed her B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) from Gujarat National Law University, India, and an Advanced LL.M. in Public International Law from Leiden University, Netherlands. She has worked with NGOs, law firms and international organizations over the years, engaging with several facets of human rights and international law. She started working with Blue Ocean Law in July 2023 and is assisting the firm in representing Vanuatu at the International Court of Justice for the Advisory Opinion on the Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change. She is currently based out of Amsterdam. You can find her on LinkedIn and X.

[1] The ILC, for instance, defines it as follows: “A peremptory norm of general international law (jus cogens) is a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a subsequent norm of general international law (jus cogens) having the same character” (see Conclusion 3).

[2] See p. 20, where the ICJ determines: “It is for Liechtenstein, as it is for every sovereign State, to settle by its own legislation the rules relating to the acquisition of its nationality, and to confer that nationality by naturalization granted by its own organs in accordance with that legislation. It is not necessary to determine whether international law imposes any limitations on its freedom of decision in this domain.”

[3] For example, Amit Shah has commented that “[f]irst we will pass the Citizenship Amendment bill and ensure that all the refugees from the neighbouring nations get the Indian citizenship. After that NRC will be made and we will detect and deport every infiltrator from our motherland” and that “[w]e will remove every single infiltrator from the country, except Buddha, Hindus and Sikhs.”

[4] This follows the definition of racial discrimination per Article 1(1) of the ICERD, which defines racial discrimination as [a]ny distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference based on race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural or any other field of public life.”

[5] See Judge Robinson’s definition of “national origin” in his Qatar v. UAE dissent (paras. 7-8): “According to the ordinary meaning of the words “national” and “origin”, the term “national origin” refers to a person’s historical relationship with a country where the people to which that person belongs are living… National origin refers not only to the place from which one’s forebears came; it may also refer to the place where one was born.”

[6] ICERD, Art. 7; International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Art. 24(3); Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, Art. 9; Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Art. 18; International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, Art. 29.

[7] On this, see the ICJ’s judgement in Questions Relating to the Obligation to Prosecute or Extradite (Belgium v. Senegal) (paras. 99-100), explaining how jus cogens norms are determined.

[8] This is reinforced via the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, Art. 1(1); the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, Art. 29, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Art. 7(1), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Art. 24(3).

[9] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Art. 53; Application of Genocide Case (Further Requests for the Indication of Provisional Measures) (Separate Opinion of Judge ad hoc Lauterpacht), para. 100; ILC, Report of the Study Group on Fragmentation of International Law: Difficulties Arising from the Diversification and Expansion of International Law, para. 365; B. Simma, ‘From Bilateralism to Community Interest in International Law’ (1994) 250(2) RdC 217–384, 289.

Cover image credit

Dec 7, 2023 | Content, Online Scholarship, Perspectives

Yohannes Takele Zewale*

Editors’ Note: Although HILJ Online: Perspectives typically publishes short-form scholarship, we occasionally publish exceptional longer pieces—such as this one.

Abstract

Descriptive representation for persons with disabilities in parliaments is not as prevalent as representation based on other identities, such as gender, race, ethnicity, and youth. However, a beacon of progress has emerged from the Global South, with only five countries—Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, and Egypt—constitutionally recognizing the right to descriptive representation for persons with disabilities. Although the reasons behind this recognition in underdeveloped democracies are not yet studied, this Article explores these factors by analyzing their laws and conducting interviews with politicians, advocates, and leaders of organizations for persons with disabilities in these African countries. By doing so, this Article aims to shed light on the noteworthy strides these countries have made in integrating persons with disabilities into their parliamentary bodies ahead of Western countries. The findings suggest that factors such as the lack of real power shared by their governments, cultural and systematic differences between these African countries and the West, strategic preferences of the Disability Rights Movement, recent constitutional review processes, and other similar factors contribute to the recognition of the right to descriptive representation of persons with disabilities ahead of Western democratic countries.

1. Introduction

Descriptive representation refers to a representation in which representatives have similar backgrounds to the voters they represent, with the trust that voters are more effectively represented by legislators similar to them in key demographic characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, or religion.[1] With descriptive representation, the composition of the representative body necessarily shows the demographics and experiences of the citizenry.[2] In other words, representatives are “in their own persons and lives, in some sense typical of the larger class of persons whom they represent.”[3] This type of representation occurs, for example, when legislators with disabilities represent persons with disabilities or when female legislators represent their female constituents.

In her seminal work, Hanna Pitkin argues that the model of Descriptive Representation posits that a representative of a minority group should, to some extent, reflect that group’s common experiences and outward manifestations.[4] However, as articulated by scholars like Anne Phillips, the descriptive representation model goes beyond mere external characteristics, encompassing the ideals and interests of minority groups.[5] Nonetheless, its efficacy in ensuring representation for persons with disabilities remains underrealized. Hendrik Hertzberg highlights the pitfalls of majoritarian plurality electoral systems, where voters often prioritize regional representation, potentially neglecting the specific concerns of marginalized groups.[6] This oversight becomes more pronounced in the case of persons with disabilities, whose dispersed nature is not adequately addressed by such electoral frameworks. Barbara Arneil and Nancy Hirschmann’s research underscores the slower progress in political science regarding disability, revealing a lack of attention to the needs of this substantial segment of society.[7] Stefanie Reher’s observation about the glaring oversight in the descriptive representation of persons with disabilities, constituting one-fifth of the population, emphasizes the urgent need for rectification.[8] In a society that values inclusivity and equal representation, addressing this gap in descriptive representation for persons with disabilities is not just a matter of political theory but a fundamental step toward ensuring the political well-being of a marginalized and underrepresented community.

However, descriptive representation of persons with disabilities in parliaments is less common than descriptive representation based on other identities, such as gender, race, ethnicity, and youth.[9] Yet, in recent years, some countries have begun to constitutionalize the representation of persons with disabilities.[10] These countries may surprise anyone who expects the West to take the lead in recognizing human rights, including the right to representation for persons with disabilities. When measured in indices such as electoral process and pluralism, civil liberties, government functionality, political participation, and political culture, countries like Uganda, Egypt, Kenya, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe are categorized as having lower levels of democracy.[11] Nevertheless, they are ahead of the West in terms of having an inclusive legislature and constitutionally recognized descriptive representation of persons with disabilities. Unfortunately, no research has been conducted to determine the factors behind the constitutional recognition of descriptive representation of persons with disabilities in these five African countries.[12] Thus, this Article explores the factors behind the early recognition of the right to descriptive representation for persons with disabilities by these five African countries, surpassing more developed democracies.

In the rest of this Article, Part II will provide a comprehensive summary of the laws implemented in various African countries that allocate parliamentary seats for persons with disabilities. Part III will delve into the findings derived from the collected interview data to synthesize the rationales behind these countries’ decision to grant the right to representation for persons with disabilities, especially in light of their relatively lower levels of democracy. Part IV will comprise a detailed discussion expanding upon the previous sections’ insights, exploring the legislative measures’ implications and consequences, and highlighting any challenges, successes, and potential recommendations for further improvement. And Part V will provide concluding remarks.

2. Background on Descriptive Disability Representation Laws in Africa

Based on the most comprehensive available evidence, it appears that only five countries in Africa have officially recognized and implemented descriptive representation of persons with disabilities within their parliaments. What makes these five countries—Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, and Egypt—truly fascinating is not just that they recognize the right of persons with disabilities to have descriptive representation in parliament. Equally noteworthy, they consciously decided to enshrine this right directly in their constitutions rather than relying on subsidiary laws. By granting this right a constitutional status, these countries have demonstrated their firm and legally binding commitment to ensuring parliamentary inclusion for persons with disabilities.

For instance, the Ugandan Constitution established a unicameral legislature,[13] which is required to enact laws favoring historically marginalized groups.[14] As a response to this constitutional call, the parliament adopted a law reserving five of the 458 seats in parliament for persons with disabilities; accordingly, there shall be five representatives with disabilities, at least one of whom being a woman.[15] A national electoral college of persons with disabilities, with five representatives from each electoral district, selects those who will occupy the five reserved seats in parliament.[16] Furthermore, every village, parish, sub-county, and district council must include at least one man and one woman with a disability.[17]

Both the Rwandan Constitution and Zimbabwean Constitution established bicameral legislatures, with Rwanda’s Chamber of Deputies and Senate[18] and Zimbabwe’s National Assembly and Senate.[19] While Rwanda and Zimbabwe both have one and two legislative seats reserved for persons with disabilities, the former has seats in the Chamber of Deputies,[20] while the latter has seats in the Senate.[21] The method they choose for selecting these representatives is similar to that of Uganda’s national electoral college of persons with disabilities.[22]

Further, the Kenyan Constitution established a bicameral legislature consisting of the National Assembly and the Senate.[23] These two houses must reflect a fair representation of marginalized groups, including persons with disabilities,[24] requiring the state to ensure the “progressive implementation of the principle that at least five percent of the members of the public in elective and appointive bodies are persons with disabilities.”[25] Additionally, the Constitution sets aside a minimum number of legislative seats for marginalized groups, including persons with disabilities.[26] Accordingly, parliamentary political parties nominate 12 members, based on proportional representation, to represent special interest groups, including persons with disabilities.[27] Two senatorial seats are reserved for two members, one man and one woman, representing persons with disabilities.[28] Also, a County Assembly must consist of members of marginalized groups, at least two of whom are persons with disabilities.[29] The members representing persons with disabilities are nominated or appointed by the winning political parties.[30]

Lastly, the Egyptian Constitution established a bicameral legislature consisting of an upper house (i.e., the Senate) and a lower house (i.e., the House of Representatives).[31] The Constitution requires the state to grant appropriate representation for minorities, including persons with disabilities, in the House of Representatives and local councils.[32] The House of Representatives consists of 596 seats.[33] Of these, 448 seats are filled through majoritarian elections, 120 are filled through party lists, and the president selects 28 representatives.[34] The country is divided into four constituencies for the list component: two 15-member and two 45-member constituencies.[35] At least one person with a disability must be listed on each list in the former, while at least three must be nominated in the latter.[36] Parties that receive more than 50 percent of the vote are given all of the seats in the constituency, ensuring that at least eight candidates with disabilities are elected to parliament.[37] Apart from the eight candidates, the president may use his power of nomination to designate additional disabled representatives.[38]

The fact that these five countries allocate parliamentary seats for persons with disabilities raises a fundamental question: How did these countries realize the right to representation of persons with disabilities in parliament ahead of Western countries with more developed democracies? This question could be answered by research interviews that advance various potential justifications.[39]

3. Rationales for Early Disability Representation Recognition

Certainly, the principle of parliamentary representation is traditionally viewed as a cornerstone for ensuring the political participation rights of any group. However, this principle undergoes nuanced scrutiny in reserving parliamentary seats for persons with disabilities, particularly in countries with varying levels of democracy. Interviewees from Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, and Egypt have shed light on a multifaceted exploration of the rationales behind this decision. Their insights delve into the intricate fabric of political cultures within their nations, the broader African continent, and Western democracies. Unveiling four key rationales, namely, the absence of genuine power-sharing, cultural and systematic disparities in political ideologies, a strategic choice by the Disability Rights Movement, and the transformative impact of recent constitutional reviews, this section synthesizes the intricate dynamics that influence the decision to grant representation rights to persons with disabilities.

3.1 No Real Power Shared

First, interviewees shed light on power-sharing dynamics in these five African countries, particularly focusing on parliamentary representation for persons with disabilities. A key theme emerged during the interviews, emphasizing that allocating parliamentary seats for persons with disabilities in these countries does not signify genuine power sharing. Instead, it is closely tied to the prevailing authoritarian rule, challenging the perception of these nations as fully democratic. The interviewees argue that, in contrast to Western democracies, the legislatures in these African countries are perceived as symbolic entities, with real power concentrated in the executive branch. They assert that these legislative bodies are, in their words, “sham institutions” where the executive branch reigns supreme. Surprisingly, persons with disabilities find representation in these symbolic legislatures rather than in the executive branch, where actual power resides. This peculiar pattern raises questions about the sincerity of political inclusion for persons with disabilities.

For example, Kenyan interviewees lament the absence of ministers or deputy ministers with disabilities in any of the 22 ministerial offices under President William Ruto. They emphasize that the representation of persons with disabilities in the Kenyan Parliament is hindered by fundamental legal gaps, preventing it from serving as a model for broader inclusion within the executive. Addressing this issue, they argue, requires substantial effort both within parliament and in executive circles. Rwandan interviewees support the “no real power shared” argument by suggesting that even if persons with disabilities secure representation in parliament, they are unlikely to challenge the power dynamics of the incumbent government. The prevailing sentiment is that obtaining a few seats in these symbolic legislatures does not threaten the government’s autocratic rule. Rwanda and Zimbabwe serve as examples where, despite political representation for persons with disabilities in parliament, real power remains concentrated in the executive branch.

Similarly, Egyptian interviewees highlight the absence of ministers or deputy ministers with disabilities in current ministerial offices, reinforcing the idea that genuine power-sharing remains elusive. Their collective perspective is that these countries cannot be considered champions of democracy simply because they allocate some parliamentary seats to persons with disabilities, placing them ahead of developed countries in terms of this specific metric. Additionally, the interviewees reference a Kenyan judge and human rights activist who cautioned against celebrating governments merely for reserving parliamentary seats for minority groups. The judge emphasized the inconsequential nature of parliamentary representation if real power remains entrenched in the executive branch. Interviewees from Uganda align with this sentiment, advocating for the simultaneous fight to involve persons with disabilities in the executive, not merely in parliament.