Tomorrow for which we are not prepared. Why is the Outer Space Treaty opposed to the idea of colonizing Mars?

*Piotr Filip Parkita

I. Potential for colonizing Mars

In May 2024, Małgorzata Polkowska published an interesting article about projects for colonizing Mars and other celestial bodies. Special attention should be given to the legal considerations she offers within the framework of contemporary space law doctrine. The international community currently lacks adequately constructed legal regulations that would comprehensively address this subject. Denis Safronov, a Russian researcher, highlighted how the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST) fails to account for the legal challenges arising from the exploration of space. There is indeed a legal gap in this area. The laws enacted in the last century are not adequate to address the challenges of modern industry and the ambitions for space development. The international community should take steps to regulate this issue.

The colonization of Mars is not a distant concept; it should be considered realistically. Mars possesses numerous resources that might facilitate human colonization. The existence of water ice is essential for supplying drinking water as well as agricultural purposes. Additionally, water can be separated into hydrogen and oxygen. These elements are vital for rocket fuel and breathing. Polkowska, for example, cited the ongoing Artemis program, which is an exciting step in human’s journey to Mars (this program is being implemented by NASA, ESA, and JAXA, among others). Artemis consists of several key elements that are expected to play a crucial role in the success of the mission, including the expansion of the Gateway station and the establishment of the Artemis Base Camp on the lunar surface.

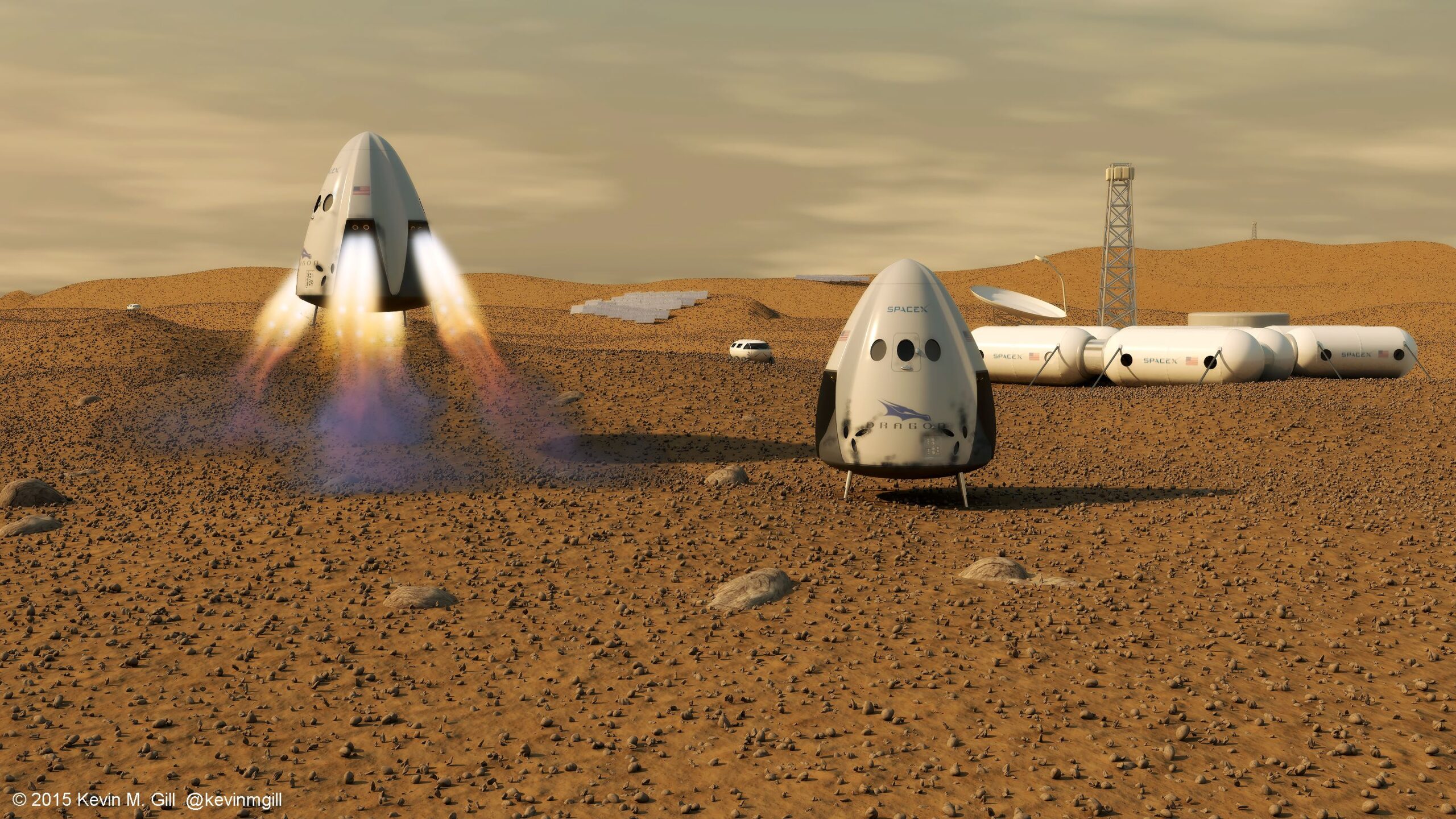

Private enterprises are intimately involved in this domain: Elon Musk, the CEO of SpaceX, projected in 2022 that his company’s inaugural manned mission to Mars might commence as soon as 2029. These plans presently seem rather ambitious. However, it is evident that the concept of colonization continues to captivate the imagination, presenting an escalating array of challenges to humanity. One of these challenges is the accurate legal classification of such activities, which necessitates a robust regulatory framework specifically addressing these ventures. Abu Rayhan noted that while “significant technological, health, ethical, and legal hurdles remain, ongoing advancements and international collaboration could make human settlement of other planets a reality in the coming decades.”

II. Problems arising from the Outer Space Treaty

Given the accelerating advancement of entities within the space industry, including those collaborating with governmental agencies, it is essential to formulate appropriate legal frameworks to facilitate the objective categorization of these activities. These entities are subject to the jurisdiction of multiple nations, which complicates the process of achieving legal harmonization. The legal regime governing the potential colonization of Mars is regulated by the OST. Other legal acts related to outer space include the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space, also referred to as the Rescue Agreement. These instruments are intended to ensure the peaceful exploration and use of outer space.

The OST is a legal instrument adopted in 1967, with 115 states as its parties. It failed to consider the issues that would arise from rapid technological advancement and the increasing presence of activities such as space tourism. Despite the fact that Mars colonization is a plausible concept that could become a reality in the near future (within the next decades or so), I refer to it as the “tomorrow for which we are not prepared.” The OST, in its current form, is not equipped to regulate actions supporting the concept of Mars colonization, which is increasingly emerging within the international community. A thorough analysis of the articles of this document (I, II, VI, VIII, IX) is necessary.

As John Clayton rightly notes, nations can withdraw from the OST with a one-year notice period, after which they are no longer constrained by the provisions of this legal instrument. This would allow states to make claims over certain areas of outer space and use them according to their national interests without restriction. Such an option appears particularly advantageous for countries with superior technological and budgetary resources, especially P5 countries on the UN Security Council. Opposition to their actions would likely be ineffective, given that the strategic advantages of space exploitation would surpass any temporary negative effects on these countries’ international relations. The P5 countries vested with veto power on the UN Security Council are China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America — leading players in the space race with equipment and technology far more advanced than those of other treaty members.

Thus, it is necessary to develop appropriate solutions that can secure the interests of smaller nations with less advanced technology in the future, allowing them to participate on more even footing in space colonization.

III. The premises undergirding colonization in the context of the Outer Space Treaty

Article I of the OST establishes a fundamental principle for the exploration and use of outer space: all such activities “shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.” This principle implies that any benefits derived from activities in outer space, including those associated with colonization or the establishment of human settlements on celestial bodies like Mars, must be shared equitably. The concept of “the province of all mankind” emphasizes that outer space is a domain where no state or entity can claim exclusive rights to the fruits of exploration, thus framing space as a collective heritage and resource.

This principle introduces a critical constraint: colonization must be universally advantageous, accessible to all countries, and cannot be exploited solely for the individual benefit of the state or private entity that initiates such efforts. This stipulation directly opposes the historical model of Earth-based colonization, where the colonizing power often derived unilateral benefits, primarily through the extraction of natural resources and the establishment of exclusive economic zones. Any space colonization must adhere to a model that prioritizes shared benefits, consistent with the spirit of global cooperation embedded in the OST.

From this perspective, the logical approach to space colonization would be through collaborative missions involving multiple countries, all of which are parties to the OST. Such joint endeavors would help ensure that the outcomes of space exploration and resource use align with the principle of the common good. Collaborative missions would facilitate the sharing of technology, scientific knowledge, and resources, thereby minimizing the risk of any single state monopolizing the advantages of space colonization.

However, the practical realization of these principles presents challenges, especially when considering the concept of terra nullius. While Mars qualifies as terra nullius (nobody’s land) under international law, the limited and non-renewable nature of its resources could eventually lead to competition and exclusive claims by states or private entities that undertake colonization efforts.

Furthermore, the historical context of Earth-based colonization demonstrates a pattern of competitive exploitation of natural resources and territory. Although space colonization differs fundamentally — given the absence of indigenous human populations and the unique legal status of outer space — the risk remains that individual states may seek to secure preferential, or worse yet, exclusive access to Martian resources in the long term. This could manifest through the construction of infrastructure, the establishment of research stations, or through long-term resource extraction activities. Such actions, if not carefully regulated, would be at odds with the cooperative framework required by Article I of the OST.

Therefore, any approach to space colonization must not only focus on technical feasibility and scientific advancement but also address these legal and ethical considerations. It must balance the interests of pioneering states with those of the broader international community, maintaining compliance with the OST’s overarching goal of ensuring that space remains a domain where benefits are equitably shared and where activities are conducted for the collective good of humanity.

A possible solution would be the introduction of a separate legal act defining the scope and possibility of claims, similar to the approach taken in the case of Antarctica, where such arrangements were adopted for a specific period. Initially, potential Martian colonies can be similar in concept to polar stations, such as the President Eduardo Frei Montalva Base, along with the inhabited outpost Villa Las Estrellas, which the Chilean government considers as part of the commune Antártica (“commune” being the smallest administrative subdivision in Chile), and thus, de facto, a part of Chilean territory. It should be noted, however, that in the case of the Antarctic Treaty, no prohibition of claims was included. In fact, this treaty somewhat “suspended in time” the claims that had already been made, for the duration of the agreement.

Particularly important is Article II of the OST: “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” This article is arguably the most problematic in this regard. A colony is a territory controlled by an independent country, but considered part of that country for relations with other countries. A colony is a territory under the jurisdiction of an independent state that maintains a relationship with that state. Puerto Rico offers a contemporary example, as it holds the status of an unincorporated territory and serves as a dependent territory of the United States.

Colonization of Mars, by its inherent definition, would inherently contradict the stipulations of Article II of the OST. Even if the colony were to lack sovereignty, or if a country were to establish a Martian colony without asserting sovereignty or national jurisdiction, it would be difficult to argue that this would not meet the threshold of “use” or “occupation” per the treaty. The establishment of a permanent or semi-permanent human settlement on Martian soil would inevitably involve the utilization of land, resources, and potentially infrastructure development, thus creating a conflict with the Article’s text.

Theoretically, establishing and maintaining a colony does not necessarily imply the appropriation of a given territory by a single state — one can look at the issue of oil platforms on the high seas, which are not subject to appropriation according to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. It is only the activities of a state concerning such a colony that may raise objections, for instance, if a state were to declare a Martian colony as its extraterrestrial territory.

While a colony may not constitute a direct claim of sovereignty by a nation-state, its presence might still be seen as an indirect exercise of control or jurisdiction, thus conflicting with the non-appropriation principle enshrined in the OST. The ambiguity in the phrase “by any other means” further complicates this interpretation, as colonization could encompass a wide range of activities beyond traditional state claims, potentially including private or corporate initiatives that result in sustained presence or control over specific areas on Mars. This raises significant legal questions regarding the compatibility of a Martian colony with the OST’s intent to preserve outer space as a domain free from national appropriation and exploitation.

According to Article VI of the OST, “States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty.” States are further responsible for the activities of private entities under their jurisdiction, meaning that private colonization cannot serve as a viable solution.

This legal framework implies that even if a private company or entity attempts to establish a colony on Mars, the state under whose jurisdiction that entity operates would still be liable for ensuring that their activities adhere to international space law. Thus, a state’s obligations under the OST cannot be circumvented through privatization or the delegation of space activities to non-state actors. The responsibility extends to supervising and authorizing the activities of private actors to ensure that their actions do not amount to prohibited appropriation or occupation of outer space, thereby maintaining compliance with the non-appropriation principle of Article II.

It is additionally essential to refer to Article VIII: “A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body. Ownership of objects launched into outer space, including objects landed or constructed on a celestial body, and of their component parts, is not affected by their presence in outer space or on a celestial body or by their return to the Earth…” This Article outlines the principle of exercising jurisdiction over an object placed (constructed) on a celestial body, such as Mars. A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, while it is in outer space or on a celestial body, as well as ownership of objects that have been constructed on a celestial body. This may refer to constructions (objects, buildings) built on a celestial body that are significant for the colony.

Moreover, a State Party to the Treaty retains jurisdiction and control over the personnel aboard an object launched into outer space when it is in outer space or on a celestial body. This raises the issue of colonists and their legal status. The problem arises when colonists come from different countries with varying legal systems. It is undeniable that people living together, tasked with building the foundations of a Martian society, may, for instance, commit certain types of crimes or find themselves in civil law conflicts. Transporting such individuals back to the Earth solely for conducting a trial would be impossible. Given the differences in legal systems, it would be worth considering the establishment of a common Martian legal system and laying the groundwork for a jurisdictional apparatus that allows for the swift and efficient resolution of legal disputes among colonists. The considerations regarding the status of a colonist can be narrowed to three main points.

First, the regulation of the status of colonists based on Article V of the OST involves adopting the definition of a colonist as an “envoy of mankind” (similar to astronauts), thereby obligating colonists from different State Parties to provide all possible assistance to colonists from other State Parties.

Second, developing a separate regulation of the status of colonists, by creating an individual legal definition would allow for the introduction of a universally accepted law intended to apply on Mars, effectively making the colonists “citizens of Mars,” subject to those planetary laws. However, this would require the creation of a quasi-state apparatus, entirely under the authority of the United Nations. This apparatus would be responsible for overseeing the administration of laws. Additionally, it would need to foster cooperation among various State Parties to ensure that the legal system is equitable and respects the rights of all colonists, regardless of their country of origin.

Third, the complete lack of regulation on this matter creates a significant legal gap, leaving important questions unresolved. This approach may be seen as appropriate, as it allows for flexibility in adapting legal frameworks to the evolving nature of Mars colonization. Defining the status of colonists too rigidly could be problematic, given the diversity of legal systems involved and the complex, shifting circumstances of space exploration. By leaving a legal gap, the international community can avoid prematurely imposing restrictive laws that might not align with future developments. Additionally, it helps preserve the sovereignty of individual states and protects against overly centralized definitions that could lead to conflicts. This open-ended approach allows for a gradual and more inclusive development of a legal system as the colonization process progresses.

The OST’s limitations also arise from Article IX, which underscores the obligations of states in the exploration and use of outer space. According to Article IX, states must adhere to the principles of cooperation and mutual assistance, ensuring that their activities are carried out with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties to the Treaty.” This provision implies a duty to consider the interests and rights of other states during space activities, including on celestial bodies like Mars.

Moreover, Article IX emphasizes the necessity of avoiding “harmful contamination” of outer space and preventing “adverse changes in the environment of the Earth” that could result from the introduction of extraterrestrial matter. States are thus required to take measures to avoid activities that might harm the space environment or impact the Earth’s ecosystem. This provision suggests that any activity, including colonization or extensive use of Martian resources, must be conducted in a manner that does not jeopardize the integrity of the Martian environment or lead to negative consequences for the Earth.

Additionally, this provision mandates that states engage in “appropriate international consultations” if they believe that their activities, or those of their nationals, could cause “potentially harmful interference” with the activities of other states. This requirement further complicates the prospect of private or unilateral colonization efforts, as it requires transparency and collaboration with the international community to avoid conflicts or interference with the peaceful exploration and use of outer space by other states. If a state believes that another state’s planned activities may be harmful, that state has the right to request consultations, ensuring that potentially disruptive actions are subject to international scrutiny before proceeding.

These obligations, derived from Article IX, reinforce the notion that space activities must prioritize cooperation, environmental preservation, and the interests of the broader international community, rendering unilateral or private colonization efforts legally and practically unrealistic under the framework of the OST.

IV. Conclusion

The conditions set forth in the OST effectively constrain any potential concept for colonizing Mars. These constraints arise from the existing framework of international law, which places significant limitations on the ways states and private entities can engage in activities on celestial bodies. While the current legal framework aims to preserve outer space as a common heritage of humanity, it also presents obstacles to the practical realization of long-term human colonization of Mars.

Given the rapid advances in space exploration and technology, a reassessment of the OST may be necessary. The changing landscape of space activities, especially the prospect of human colonization beyond the Earth, suggests that the current legal provisions may not adequately address the complexities and challenges posed by such endeavors. There is a growing need to develop new and tailored frameworks for regulating the colonization of Mars while maintaining the principles of international cooperation and equity that underpin the OST.

The international community should engage in a comprehensive dialogue to establish new legal and regulatory frameworks for the colonization of Mars. These frameworks should be designed with a focus on sustainable development, ensuring that the exploitation of Martian resources does not lead to environmental degradation, either on Mars or through potentially adverse impacts on Earth. Additionally, any revised legal regime should safeguard the human rights of the “colonizers,” ensuring that their well-being and safety are protected under international standards.

These regulations should aim to balance the interests of pioneering states with those of the broader international community. This includes ensuring equitable access to resources and opportunities in space, as well as protecting the Martian environment from harmful contamination. Such measures would require clear rules regarding resource extraction, waste management, and ecological preservation, as well as mechanisms for resolving disputes that may arise from conflicting claims over resources or territory on Mars.

The revision of the OST and the creation of new legal frameworks should aim to align with the core principles of the treaty, while adapting to the new realities of space exploration. By fostering international collaboration and focusing on the principles of sustainable and responsible space exploration, the global community can work towards a future where Mars colonization, if undertaken, is conducted in a manner that benefits all of humanity and respects the inherent value of the Martian environment. This process would ensure that any future settlements on Mars do not repeat the mistakes of past terrestrial colonization, but rather, set a new standard for ethical and sustainable human presence beyond the Earth.

[hr gap=”1″]

* Piotr Filip Parkita is a law student at the Faculty of Law and Administration of the University of Lodz (Poland).