Due Process Denied: A Case Study on the Failures of U.S. Affirmative Asylum

Anna R. Welch and Sara P. Cressey*

With this new [asylum] program in place, we will be better equipped to carry out the spirit and intent of the Refugee Act of 1980 by applying the uniform standard of asylum eligibility, regardless of an applicant’s place of origin. We can thus implement the law based on a fair and consistent national policy and streamline what has sometimes been a long and redundant process.[1]

Gene McNary, Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, in remarks given weeks before opening of first asylum offices.

***

Amelia fled her home country in central Africa after the country’s repressive ruling regime singled her out based on her perceived political affiliations, subjected her to severe physical and sexual violence, murdered her sibling, and kidnapped and likely killed one of her children.[2] After arriving in the United States, she found an attorney who assisted her in preparing and submitting her affirmative asylum application along with extensive supporting documentation, including expert medical reports documenting the ongoing physical and psychological effects of her trauma. A year after submitting her application, Amelia had her asylum interview with a hostile asylum officer who spent several hours interrogating her as she recounted the harrowing persecution she had suffered. Another year of waiting passed before Amelia received a request for additional evidence and a notice that she would need to attend a second interview at the asylum office. Amelia complied with both notices but was nevertheless referred to immigration court, where she spent another five years awaiting a merits hearing. She was finally granted asylum by an immigration judge eight years after her original asylum application was filed.

Introduction

America’s promise of safe haven to those fleeing from persecution, an obligation enshrined in both international and domestic law,[3] too often remains unfulfilled, particularly for racial minorities and other marginalized groups. Indeed, the right to seek asylum at the southern border has been virtually nonexistent since Title 42 was implemented in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic.[4] Meanwhile, those who do manage to make it into the United States to lodge an asylum claim face a Byzantine administrative process plagued by “monumental” backlogs, leading to years-long (or even decades-long) wait times.[5] This Article focuses on one particular aspect of the asylum system, reporting on the first ever comprehensive study into the inner workings of an asylum office in the United States.[6] The findings of the study, set forth in the full report “Lives in Limbo: How the Boston Asylum Office Fails Asylum Seekers,” reveal larger systemic failures within the broader affirmative asylum system.[7]

The investigation into the Boston Asylum Office, spearheaded by lead investigator Anna Welch, involved both qualitative and quantitative research methods. Researchers analyzed documents and data produced by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in response to litigation brought to compel compliance with a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, as well as USCIS Quarterly Stakeholder Reports. In addition, researchers conducted more than one hundred interviews with former supervisory asylum officers, former asylum officers, immigration attorneys, asylum seekers, and asylees. The research was completed in January 2022, and the report was released to the public on March 23, 2022. This Article reproduces the findings of the report, presented as a resource for practitioners, scholars, and policymakers. The report’s major conclusion is that the Boston Asylum Office maintains an asylum grant rate well below that of the national average.[8]

The Refugee Act of 1980 formalized the right to seek asylum in the United States, but “the law itself did little to define or prescribe the mechanics of obtaining this status.”[9] During the 1980s, the adjudication of affirmative asylum applications was governed by a set of interim regulations[10] under which immigration officers within Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) District Offices would adjudicate asylum claims.[11] During that period, criticism of the INS abounded as “unspecialized, under-paid, and over-worked” INS officers[12]struggled to apply the complex refugee definition.[13] On July 27, 1990, the INS issued a final rule establishing procedures to be used in determining asylum claims and mandating the creation of “a corps of professional Asylum Officers” who would receive specialized training in international law and conduct asylum interviews in a nonadversarial setting.[14] The INS then established – for the first time – seven asylum offices, with the goal of creating a fairer and uniform affirmative asylum process.[15]

Federal regulations still require that asylum officers receive “special training in international human rights law” and “nonadversarial interview techniques.”[16] USCIS training materials for asylum officers emphasize the importance of the nonadversarial interview:

It is not the role of the interviewer to oppose the principal interviewee’s request or application. Because the process is non-adversarial, it is inappropriate for you to interrogate or argue with any interviewee. You are a neutral decision- maker, not an advocate for either side. In this role you must effectively elicit information from the interviewee in a non- adversarial manner, to determine whether he or she qualifies for the benefit. . . . The non-adversarial nature of the interview allows the applicant to present a claim in an unrestricted manner, within the inherent constraints of an interview before a government official.[17]

Unfortunately, the affirmative asylum system remains plagued by many of the issues that the 1990 final rule was intended to solve. As discussed in detail below, the process for adjudicating affirmative asylum claims remains long and difficult and too often leads to inconsistent outcomes based on the applicant’s country of origin. The more informal, non-adjudicative framework for adjudicating asylum claims in the asylum offices lacks transparency and creates an opportunity for hostility and bias to permeate the decision-making process.

I. Summary of Major Findings

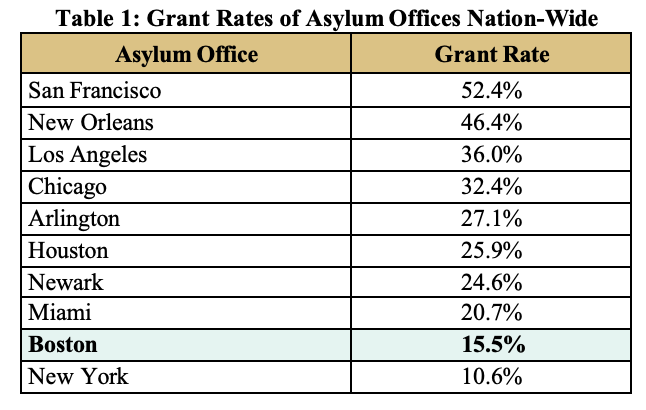

The Boston Asylum Office maintains an asylum grant rate well below that of the national average. Examining the average nationwide grant rate of asylum offices between 2015 and late 2020, we found that the Boston Asylum Office granted a little over 15 percent of its cases as compared to the national average grant rate of 28 percent. Examining monthly grant rates, we found that the Boston Asylum Office’s grant rates dropped into the single digits on multiple occasions. While the Boston Asylum Office maintains the second lowest grant rate in the country, several asylum offices around the country also maintain grant rates below that of the national average.

Indeed, many of the problems identified in this study are likely not isolated problems but rather are reflective of larger systemic failures pervasive in other asylum ffices around the country. As part of this study, we interviewed former asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers from asylum offices around the country. Many noted the prevalence of biased decision-making, the outsized role of upper management and/or supervisory asylum officers, and insufficient time to complete their job functions. Yet their functions are critical to ensuring U.S. compliance with international and domestic asylum protections.

We ultimately find that the Boston Asylum Office is failing asylum applicants in violation of international obligations and U.S. domestic law. The Boston Asylum Office’s biased and combative asylum interview process, asylum backlog, and years-long wait for adjudication has had devastating impacts on applicants and their families. If an asylum officer does not grant a case, the case is typically referred to immigration court, an intentionally adversarial setting.[18] Although the Boston Immigration Court has a significantly higher asylum grant rate than the Boston Asylum Office,[19] asylum applicants face even lengthier backlogs before being heard by an immigration judge, leading to further delay.[20] As a result, asylum seekers face years of legal limbo, rendering many individuals ineligible for social services and contributing to significant instability. The years-long wait to be granted asylum causes lengthy separation from family members (many of whom remain in life-threatening danger) and deterioration of the applicant’s mental health.[21]

Specific Findings:

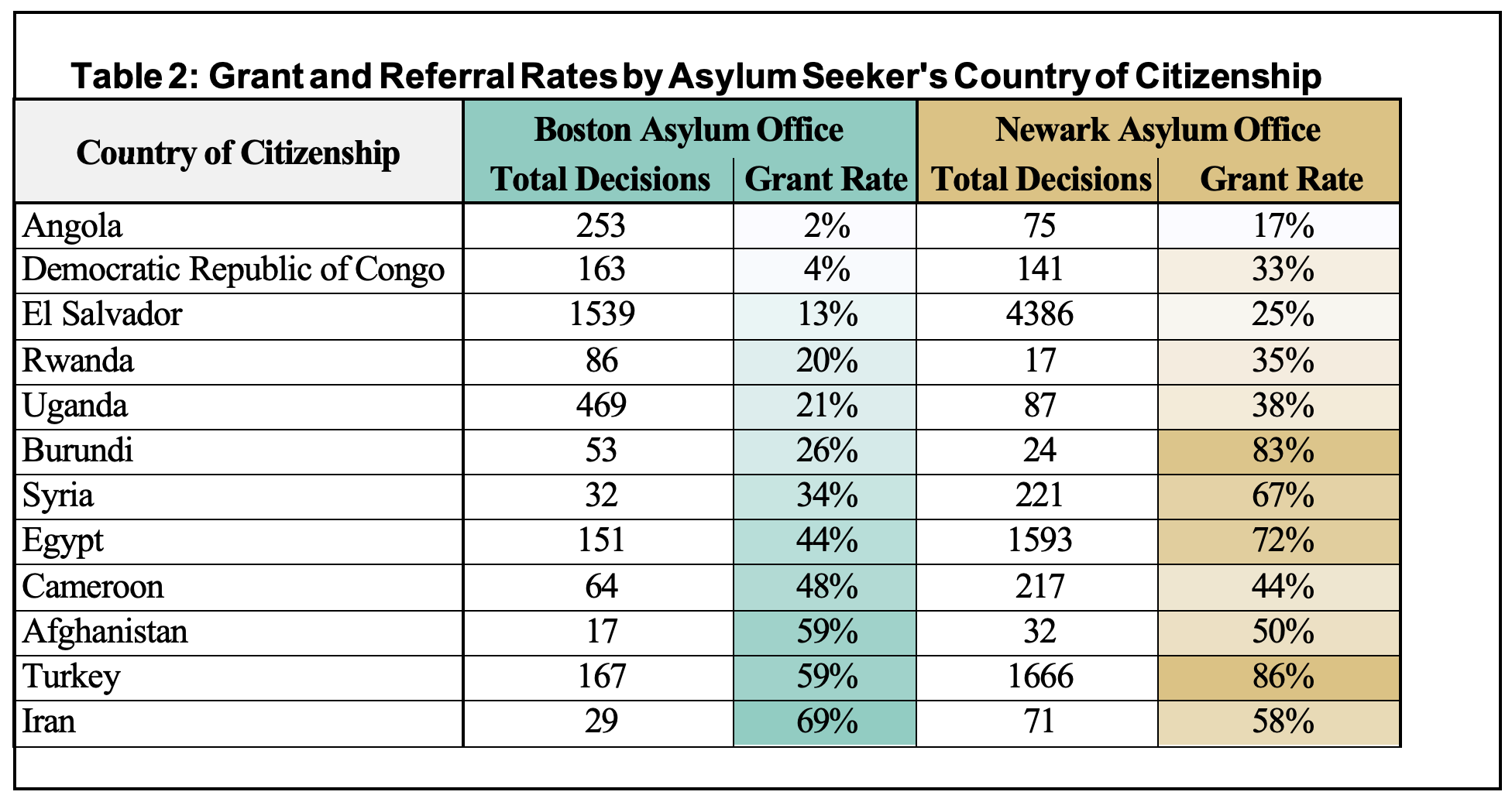

First, the Boston Asylum Office exhibits bias against applicants from certain countries as well as a bias against non-English speakers, as displayed in Table 2 below.

The Boston Asylum Office does not maintain a nationality-neutral determination process, as mandated by international and domestic law. Notably, applicants from certain countries – including Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, and Burundi – experience lower grant rates in the Boston Asylum Office than in the Newark Asylum Office.[22] From 2015 to 2020, the Boston Asylum Office granted asylum to just four percent of asylum applicants from the DRC despite extensive documentation of human rights abuses in the DRC. Indeed, the U.S. Department of State has acknowledged year after year that “significant human rights” abuses occur in the DRC, including that DRC security forces commit “unlawful and arbitrary killings . . . forced disappearances, [and] torture” against citizens.[23]

Interviews with asylum attorneys confirmed the prevalence of biased decision-making among adjudicators in the Boston Asylum Office. One asylum attorney noted, “the belief of the Boston Asylum Office is that [clients from certain African countries] are not telling the truth . . . We have taken a number of cases that have been referred from the Boston Asylum Office and then we have won them in court without a problem and there has been no suspicion about negative credibility.”[24]

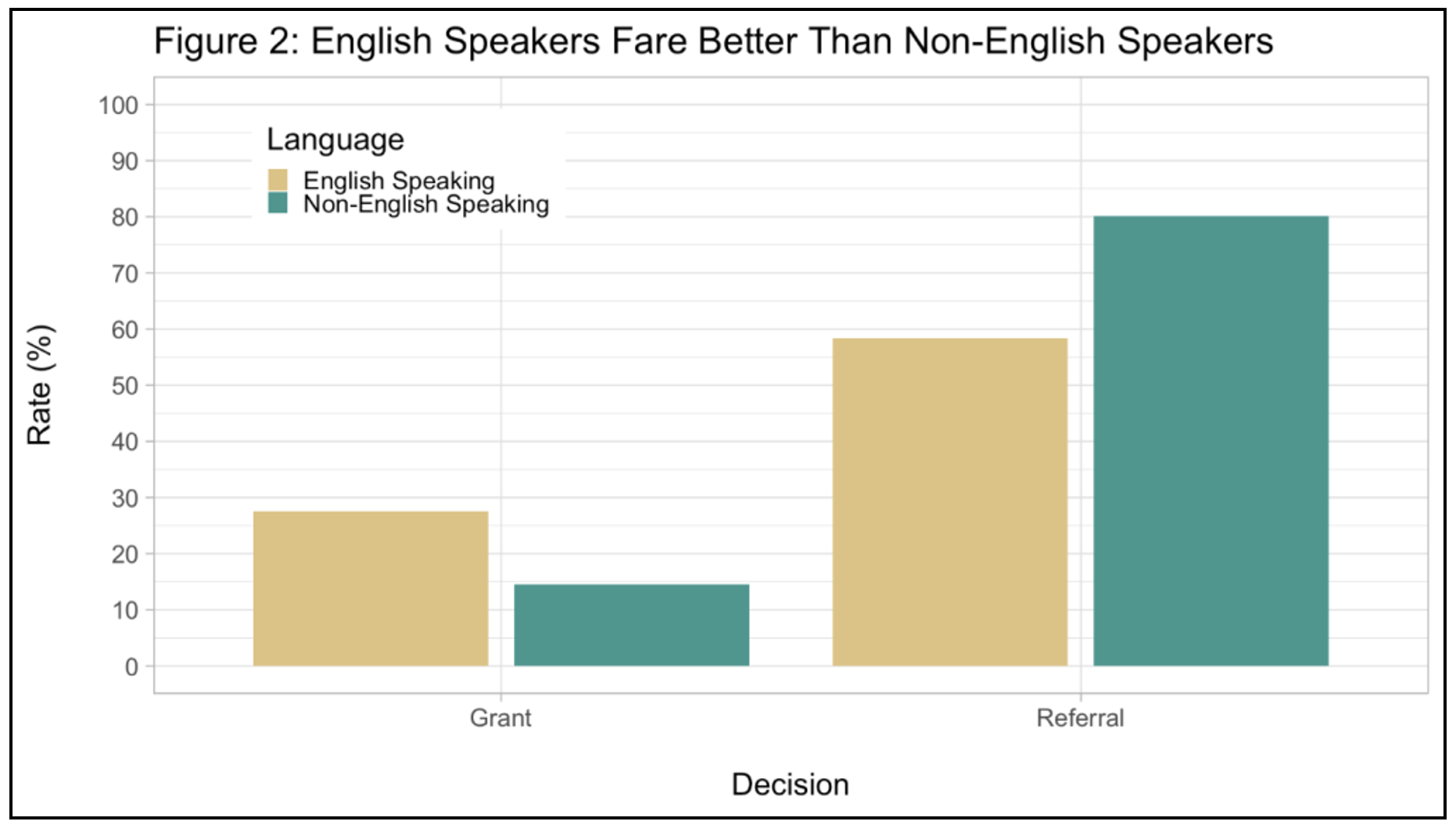

Moreover, data collected from our FOIA request revealed that English speakers are much more likely to be granted asylum in Boston than non-English speakers, even though speaking English is irrelevant to an individual’s eligibility for asylum.

As demonstrated in Figure 2 above, English-speaking asylum seekers are nearly twice as likely to be granted asylum as compared to non-English speakers. Conversely, non-English speakers are referred to immigration courts 80 percent of the time, while English speakers are referred to immigration court only 58 percent of the time.[25]

Second, the Boston Asylum Office’s low grant rate is likely driven by the oversized role for supervisory asylum officers. Although the Affirmative Asylum Procedures Manual requires that asylum officers be given “substantial deference” in deciding whether to grant a case,[26] we found that supervisory asylum officers exercise a high degree of influence over decisions made by asylum officers.

One supervisory asylum officer familiar with the Boston Asylum Office observed that the asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers hired in Boston generally trended against granting asylum.[27] Every decision rendered by an asylum officer must go through supervisory review. When a supervisory asylum officer returns an application to an asylum officer for further review or reconsideration, this creates additional work for the asylum officer. The officer may be forced to conduct additional investigation or even re-interview the asylum seeker to support their original decision. This additional work can lead to negative performance reviews because supervisory asylum officers can give asylum officers negative performance reviews if their decisions require reconsideration. Additionally, asylum officers are evaluated, in part, on the number of decisions they issue during a given timeframe. In light of these negative impacts, asylum officers are incentivized to write decisions their supervisor agrees with, regardless of whether they think a given applicant meets the requirements for asylum.

Third, asylum officers face time constraints and high caseloads that incentivize them to cut corners. By the end of 2021, the Boston Asylum Office’s backlog of asylum cases had grown to over 20,000 pending applications.[28] To ensure that asylum seekers fleeing persecution receive adequate due process, asylum officers are responsible for a lengthy list of job duties. These include conducting interviews with asylum applicants and engaging in a thorough review of an asylum applicant’s oral testimony and written documentation. Asylum officers must also remain abreast of ever-changing asylum laws and policies and country conditions. Several former asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers stated that they simply lacked the time to complete their required jobs. They reported feeling that they needed to rush through their review of asylum applications and decision drafting, even going as far as to recycle old decisions.[29]

Fourth, we found that compassion fatigue and burnout lead to lower grant rates. Former asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers observed that after time they became desensitized to the traumatic stories that accompany most asylum applications. One former asylum officer stated that asylum applicants’ traumatic stories became so “mundane as to lose salience.”[30] Troublingly, this skepticism is apparent to those appearing before the asylum officers. Asylum applicants and their attorneys noted that asylum officers were often dismissive of the asylum applicant’s trauma and were sometimes even combative with applicants. As discussed above, U.S. regulations require that asylum interviews be non-adversarial, meaning that an asylum officer must not argue with or interrogate an asylum applicant.[31] However, many asylum attorneys commented that asylum officers took an adversarial and combative approach with applicants, in direct violation of U.S. law.[32]

Finally, we found that asylum officers disproportionately focus on an asylum applicant’s credibility and small, peripheral details to find “inconsistencies” rather than the salient facts of an applicant’s case.[33] Their search for “inconsistencies” fails to recognize that many asylum seekers have experienced trauma and may suffer PTSD-induced memory loss. Moreover, given the massive asylum backlogs across the country,[34] it is very common for years to go by between the asylum applicant’s traumatic experience in their country and their asylum interview. Those years of waiting can lead to faded memories, particularly with respect to details about specific dates, times and smaller events.

II. Recommendations

We now turn to several recommendations to help address failures in U.S. compliance with international and domestic asylum protections.

First, the Boston Asylum Office must develop enhanced transparency and accountability. We call for a U.S. Government Accountability Office investigation into the Boston Asylum Office and recommend replacing asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers who demonstrate bias and/or a lack of cultural literacy. We also call for a system to mitigate the outsized role that supervisory asylum officers play in swaying the decisions of asylum officers.

Second, we recommend that all asylum interviews be recorded and that those recordings be made available to asylum applicants and their attorneys, where applicable. Currently, asylum interviews at all asylum offices around the country take place behind closed doors with no recordings or written transcripts. The only written record of what took place during an asylum interview is the asylum officer’s notes. Such notes are often not reflective of what happened during the interview, incomplete, riddled with errors. Absent an accurate recording or transcript, asylum officers may employ improper practices, such as adversarial, insensitive and biased interview techniques, with impunity. This is especially true if the asylum applicant does not have an attorney to bear witness to what occurred during the interview. Importantly, the creation and preservation of accurate records of asylum interviews is critical to ensuring that asylum seekers’ due process rights are realized in immigration court. The asylum officer’s notes and assessments are often used to impeach asylum applicants in immigration court even if they are not reflective of what was said during the interview.

Third, we call for more support and resources for asylum offices. We recommend limiting officers to one interview per day, instituting more rigorous hiring standards, support structures, and mentorship, and improving asylum officer training, with a focus on mitigating bias and racism. We also recommend developing more asylum officer trainings on trauma, compassion fatigue, and cultural literacy.

Fourth, we recommend a paper-based adjudications process that would take the place of the asylum interview when it is clear asylum should be granted based on the evidence submitted. This would help address the backlog and preserve resources by limiting asylum interviews to cases where the outcome is less certain, or where credibility or national security are relevant concerns.

Finally, we recommend ending the “last-in, first-out” (LIFO) policy that prioritizes the adjudication of cases most recently filed.[35] The LIFO policy extends wait times for hundreds of thousands of asylum applicants whose cases have already been pending for years.36

Conclusion

Since this study was released in March 2022, several members of Congress from Massachusetts and Maine called on the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General to investigate the Boston Asylum Office to hold the office accountable.37 To date, an investigation has not yet been granted, and the issues brought to light by this study remain pressing.

The Boston Asylum Office has instituted several changes that we hope will bring it into better compliance with its legal obligations. These changes include increasing the number of asylum officers and overhauling supervisory staff. The office has also added a “section chief” who is tasked with ensuring that asylum officers make legally correct decisions, rather than decisions that respond to pressures from supervisory asylum officers.

While these developments are certainly encouraging, the troubling fact remains that practices at the Boston Asylum Office have diverged significantly from the requirements of U.S. and international asylum protections. To ensure that asylum seekers in New England receive the protection to which they are entitled, monitoring data and practices of the Boston Asylum Office remains necessary. As it stands, stories like Amelia’s who, as mentioned at the outset, was forced to wait over eight years for her asylum case to be finally adjudicated are far too common, leading asylum seekers with meritorious claims to remain in limbo for years, unable to petition for family members who may still be living in danger.

Our sincere hope is that other advocates will use this first-of-its’s-kind case study as a model. Although the study focused on one asylum office, the issues we uncovered reveal larger systemic patterns likely pervasive throughout the United States affirmative asylum system. Given the life-or-death stakes in asylum cases, additional investigation remains imperative to ensure due process is realized for asylum seekers.

* * *

[*] Clinical Professor Anna Welch is the founding director of the University of Maine School of Law’s Refugee and Human Rights Clinic. Sara Cressey is the Staff Attorney for the Refugee and Human Rights Clinic. The authors express our sinceregratitude to the current and former Refugee and Human Rights Clinic student attorneys who devoted countless hours topreparing and writing the report entitled Lives in Limbo: How the Boston Asylum Office Fails Asylum Seekers, upon which thisArticle is based, including Emily Gorrivan (’22), Grady Hogan (’22), Camrin Rivera (’22), Jamie Nohr (’23), and Aisha Simon (’23). The report was also made possible by volunteers Adam Fisher and Alex Beach, who conducted valuable analysis of data collected from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Finally, the authors are indebted to the Clinic’s collaborators who co-authored the report: the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project (ILAP), American Civil Liberties Union ofMaine (ACLU of Maine), and Basileus Zeno, Ph.D. The report received the Clinical Legal Education Association’s 2022 Award for Excellence in a Public Interest Case or Project. An extended version of this piece is forthcoming in early 2024 in Volume 57, Issue 1 of the Loyola of L.A. Law Review.

[1] Gene McNary, INS Response to Immigration Reform, 14 IN DEFENSE OF THE ALIEN 3, 6 (1991).

[2] This story is drawn from the stories of multiple clients of the Refugee and Human Rights Clinic. Names and details have been changed to protect the privacy of those clients and preserve confidentiality.

[3] Congress enacted the Refugee Act of 1980 to bring the United States into conformity with international standards for the protection of refugees established by the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status ofRefugees. See S. REP. No. 96-256, at 4 (1980), as reprinted in 1980 U.S.C.C.A.N. 141, 144.

[4] Between March 2020 and April 2022, Border Patrol expelled 1.8 million migrants under Title 42, the vast majority of whom came from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. John Gramlich, Key Facts About Title 42, the Pandemic Policy That Has Reshaped Immigration Enforcement at U.S.-Mexico Border, PEW RESEARCH CENTER (Apr. 27, 2022), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/04/27/key-facts-about-title-42-the- pandemic-policy-that-has-reshaped-immigration-enforcement-at-u-s-mexico-border/; see also Human Rights Watch, US: Treatment of Haitian Migrants Discriminatory (Sept. 21, 2021), https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/09/21/us-treatment-haitian-migrants-discriminatory (“Title 42 . . . singles out asylum seekers crossing into the United States at land borders – particularly from Central America, Africa, and Haiti who aredisproportionately Black, Indigenous, and Latino – for expulsion.”). Those expelled under Title 42 have faced life- threatening violence either in Mexico or in the countries from which they originally fled. See, e.g., Julia Neusner, A Year After Del Rio,Haitian Asylum Seekers Expelled Under Title 42 Are Still Suffering, HUMAN RIGHTS FIRST (Sept. 22, 2022), https://humanrightsfirst.org/library/a-year-after-del-rio-haitian-asylum-seekers-expelled-under-title-42-are-still-suffering/; Kathryn Hampton, Michele Heisler, Cynthia Pompa, & Alana Slavin, Neither Safety Nor Health: How Title 42 Expulsions HarmHealth and Violate Rights, Physicians for Human Rights (July 2021), available at https://phr.org/our-work/resources/neither-safety-nor-health/.

[5] Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), A Mounting Asylum Backlog and Growing Wait Times (Dec. 22,2021), https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/672/; see also Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), Immigration Court Asylum Backlogs (Oct. 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/asylumbl/.

[6] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services operates ten asylum offices within the United States. See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Fiscal Year 2021 Report to Congress: Backlog Reduction of Pending Affirmative Asylum Cases, at 4 (Oct. 20, 2021), available at https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-12/USCIS%20-%20Backlog%20Reduction%20of%20Pending%20Affirmative%20Asylum%20Cases.pdf. The asylum offices are responsible for adjudicating affirmative asylum applications filed by asylum seekers who are not otherwise in removal or deportationproceedings. See 8 C.F.R. § 208.2(a)-(b).

[7] University of Maine School of Law, American Civil Liberties Union of Maine, and Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project, “Livesin Limbo: How the Boston Asylum Office Fails Asylum Seekers” (March 2022), available at https://mainelaw.maine.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/Lives-in-Limbo-How-the-Boston-Asylum-Office-Fails-Asylum-Seekers-FINAL-1.pdf (hereinafter “Lives in Limbo”).

[8] See id. at 3-4. The report’s authors analyzed data pertaining to asylum applications adjudicated by the Boston and Newark Asylum Offices between 2015 and 2020. Unfortunately, available data for decisions made since the end of 2020 suggests that the trends at the Boston Asylum Office have remained consistent. In the first quarter of 2022, the office’s approval rate remained at eleven percent. See U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Servs., I-589 Asylum Summary Overview, at 10, available at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf.

[9] Gregg A. Beyer, Establishing the United States Asylum Officer Corps: A First Report, 4 INT’L J. REFUGEE L. 455, 458 (1992).

[10] See Aliens and Nationality; Refugee and Asylum Procedures, 45 Fed. Reg. 37392, 37392 (June 2, 1980); Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 52 Fed. Reg. 32552-01, 32552 (Aug. 28, 1987); Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 53 Fed. Reg. 11300-01, 11300 (Apr. 6, 1988); Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 55 Fed. Reg. 30674-01, 30675 (July 27, 1990).

[11] Id. at 459.

[12] Gregg A. Beyer, Affirmative Asylum Adjudication in the United States, 6 GEO. IMMIGR. L.J. 253, 274 (1992).

[13] Id. at 268-69.

[14] See Aliens and Nationality; Asylum and Withholding of Deportation Procedures, 55 Fed. Reg. 30674-01, 30680, 30682 (July 27, 1990) (to be codified at 8 C.F.R. pt. 208).

[15] Beyer, supra note 6, at 470.

[16] 8 C.F.R. § 208.1(b).

[17] U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS.: REFUGEE, ASYLUM, & INT’L OPERATIONS DIRECTORATE OFFICER TRAINING, INTERVIEWING – INTRODUCTION TO THE NON- ADVERSARIAL INTERVIEW, at 15-16 (Dec. 20, 2019), available at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/foia/Interviewing_-_Intro_to_the_NonAdversarial_Interview_LP_RAIO.pdf.

[18] 8 U.S.C. § 1229a(b)(1) (“The immigration judge shall administer oaths, receive evidence, and interrogate, examine, and cross-examine the alien and any witnesses.”).

[19] Compare Exec. Off. for Immigr. Review, Adjudication Statistics: FY 2022 ASYLUM GRANT RATES BY COURT, available at https://www.justice.gov/eoir/page/file/1160866/download (showing an asylum grant rate of nearly 30% for the Boston Immigration Court in Fiscal Year 2022), with U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS., I-589 AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM SUMMARYOVERVIEW FY 2022 Q1 (OCT 1, 2021 – DEC 31, 2021), at 10, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf (showing an asylum grant rate of approximately 11% for the Boston Asylum Office in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2022). Many asylum offices have approval rates below that of the immigration courts. In fact, the most recent data reported by the Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse revealed that over three quarters of the asylum cases referred to the immigration courts by the asylum offices are granted. See Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), “Speeding Up the Asylum Process Leads to Mixed Results,” (Nov. 29, 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/reports/703/ (“Over three- quarters (76%) of cases USCIS asylum officers had rejected were granted asylum on rehearing by Immigration Judges.”).

[20] See Jasmine Aguilera, A Record-Breaking 1.6 Million People are now Mired in U.S. Immigration Court Backlogs, TIME, https://time.com/6140280/immigration-court- backlog/; TRAC Immigration, Immigration Court Backlog Now Growing Faster Than Ever, Burying Judges in an Avalanche of cases (Jan. 18, 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/675/;Transactional Record Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), Immigration Court Asylum Backlogs (October 2022), https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/asylumbl/.

[21] Interview with asylum attorney (November 2021) (“[My client is] having severe depression. This has derailed his life . . . I’ve never seen an individual on the brink of a nervous breakdown. I don’t know if he’ll survive this or overcome this.”).

[22] Data from the Newark Asylum Office provides a useful comparison because prior to the creation of the Boston Asylum Office, the Newark Asylum Office adjudicated affirmative asylum cases for the Boston region with a higher average grant rate than the Boston Asylum Office.

[23] U.S. Dep’t of State, Democratic Republic of Congo 2020 Human Rights REPORT (Mar. 30, 2021),https://www.state.gov/reports/2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices/democratic-republic-of-the-congo/.

[24] Interview with asylum attorney (January 2022). See Interview with asylum attorney (August 2021) (“From my experiences with clients in the Boston Asylum Office, there seem to be people at the Boston Asylum Office who set the mindset against certain ethnic groups or nationalities. . . it’s like they default to ‘everybody’s a liar.’”); Interview with asylum attorney (November 2021) (stating that when he appeared in the Boston Immigration Court, some judges have asked why certain cases were referred from the asylum office, expressing exasperation that these cases are adding to the court’s backlog where they were clearly approvable at the affirmative level).

[25] This, in turn, leaves asylum seekers in legal limbo and drains government resources.

[26] Affirmative Asylum Procedures Manual, U.S. CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGR. SERVS., RAIO, Asylum Division, 27 (May 17, 2016), https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/guides/AAPM-2016.pdf (“It is not the role of the SAO to ensure that the AO decided the case as he or she would have decided it. AOs must be given substantial deference once it has been established that the analysis is legally sufficient.”).

[27] Interview with former supervisory asylum officer familiar with the Boston Asylum Office (November 2021) (explaining that the asylum officers and supervisory asylum officers initially hired at the Boston Asylum Office “tended to be people who did not grant [asylum] that much,” and noted that supervisory asylum officers are given “a lot of leeway” in refusing to give the asylum seeker the “benefit of the doubt.”).

[28] U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS., I-589 AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM SUMMARY OVERVIEW FY2022 Q1 (OCT 1, 2021–DEC 31, 2021), at 12, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf (listing the Boston Asylum Office’s affirmative asylum caseload as 20,900 as of December 31, 2021). Backlogs in asylum cases are not unique to the Boston Asylum Office. Nationally, the backlog reached a “historic high” during the Trump Administration, with over 386,000 pending applications by the end of fiscal year 2020. HUM. RTS. FIRST, PROTECTION POSTPONED: ASYLUM OFFICE BACKLOGS CAUSE SUFFERING, SEPARATE FAMILIES, AND UNDERMINE INTEGRATION 1-4 (Apr. 9, 2021), https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/ProtectionPostponed.pdf.

[29] Interview with former supervisory asylum officer (November 2021) (“The abuse or temptation to short circuit and not do a full-fledged asylum interview is great for officers who have a tremendous backlog.”); Interview with former asylum officer (December 2021) (“There is a perverse incentive to rush through cases. Asylum officers have a stack of cases and they must turn them around quickly . . . We interview so many applicants with similar claims and many of us ended up recycling decisions, plugging in new facts and doing similar credibility assessments.”).

[30] Interview with former asylum officer (December 2021) (“This response is absolutely part of the trauma asylum officers hold from doing this work . . . Asylum officers are just exhausted. We are hearing stories of torture and abuse, often involving children, and it’s really exhausting and there’s no real support or even acknowledgement of the impact on us.”).

[31] 8 C.F.R. § 208.1(b); see also U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS.: REFUGEE, ASYLUM, & INT’L OPERATIONS DIRECTORATE OFFICER TRAINING, INTERVIEWING – INTRODUCTION TO THE NON-ADVERSARIAL INTERVIEW, at 15-16 (Dec. 20, 2019), available at https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/foia/Interviewing_-_Intro_to_the_NonAdversarial_Interview_LP_RAIO.pdf (instructing that AOs are “neutral decision-maker[s]” and thus must maintain a “neutral and professional demeanor even when confronted with . . . a difficult or challenging [asylum seeker] or representative, or an [asylum seeker] whom [the AO] suspect[s] is being evasive or untruthful”).

[32] Former asylum attorney interview (November 2021) (“The client was a survivor of torture and [the officer] laughed multiple times throughout the client telling her story . . . She checked her test messages during the interview . . . The [applicant] was pouring his heart out to this person and she’s laughing . . . and yet when she is engaged, she’s cross examining him up and down.”).

[33] Interview with asylum attorney (January 2022) (“Questions seemed to be a direct way to suggest that the client was not credible . . . it was completely unnecessary and not relevant and really insensitive to the fact that [the client] was super traumatized and trying to recount horrific details about violence they experienced.”).

[34] See U.S. CITIZENSHIP & IMMIGR. SERVS., I-589 AFFIRMATIVE ASYLUM SUMMARY OVERVIEW FY2022 Q1 (OCT 1, 2021 – DEC 31, 2021), at 12, https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/data/Asylum_Division_Quarterly_Statistics_Report_FY22_Q1_V4.pdf (listing number of pending asylum cases in each asylum office as of December 31, 2021).

[35] See Archive of Press Release, U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., USCIS to Take Action to Address Asylum Backlog (Jan. 31, 2018), available at https://www.uscis.gov/news/news-releases/uscis-take-action-address-asylum-backlog. The LIFO policy was implemented by the Trump administration, “to deter those who might try to use the existing [asylum] backlog as a means to obtain employment authorization,” id., and remains in effect today. See U.S. Citizenship & Immigr. Servs., Affirmative Asylum.

Cover image credit

Somewhere Over a Green Rainbow?—The Overlooked Intersection between the Climate Crisis and LGBTQ Refugees

Eoin Jackson*

The international community drafted the UN Refugee Convention (hereinafter ‘The Convention’) with the horrors of the Second World War still fresh in its mind. At the time, LGBTQ people were illegal in most countries and climate change was the stuff of scientific fantasy.[1] Despite this historical context, activists have sought to use the Convention to protect LGBTQ refugees, and now seek to achieve similar success with recognizing climate refugees.

This article analyzes the intersection between recognition of LGBTQ people as refugees and the potential recognition of climate refugees. It intends to briefly sketch out how the climate crisis might exacerbate issues faced by LGBTQ people such that their circumstances may escalate to the point where formal recognition under the Convention would be justified. It also examines how a queer lens could help advance efforts to formally recognize climate refugees under the constraints of the contemporary approach. Part I of this article analyzes the impacts of the climate crisis on LGBTQ refugees. Part II criticizes the recent Human Rights Committee decision in Teitiota v. New Zealand (2020)[2] for failing to consider the differentiated impact of climate change on vulnerable communities. Part III outlines suggestions for future efforts to recognize LGBTQ refugees and intersects these suggestions with the broader movement to recognize climate refugees.

Part I: The LGBTQ Community and the Climate Crisis

LGBTQ people are generally recognized as refugees using the ‘protected social group’ element of the Convention.[3] Most asylum officers will focus on whether there is a nexus between the sexuality/gender identity and persecution of the applicant.[4] Typically, this analysis involves an examination of home countries’ laws, attitudes, and policing of homosexuality/gender identity. Persecution of LGBTQ refugees includes considering how these laws and attitudes impact the capacity of the LGBTQ person to freely express their sexuality/gender identity.[5]

Importantly, many LGBTQ refugees are from the same countries where climate change is likely to have the most immediate impacts. These countries are found in regions of Northern Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East.[6] In other words, countries’ existing poor track records on LGBTQ issues will now face additional social and economic challenges because of climate change.[7] Resources which could have been used to address social progress will need to be diverted to climate mitigation and adaptation measures.[8] This phenomenon most starkly exists in Pakistan, where large government resources will need to be devoted to addressing the impact of devastating floods.[9] However, as tensions increase in countries experiencing extreme weather changes and natural disasters, so does the possibility of groups who deviate from norms being blamed for the crisis. During the Covid-19 pandemic, for instance, LGBTQ people were blamed for the outbreak by leaders in Nigeria, Liberia, and Zimbabwe, among others.[10] Violence and state repression against LGBTQ people also increased during Covid-19, with many LGBTQ centers shut down and people arrested.[11] Should this pattern repeat itself, LGBTQ people will increasingly face demonization under the pretense of being the ‘cause’ of the relevant climate disaster. This demonization may also happen in countries which, at least on paper, have LGBTQ protections or have legalized homosexuality. The instability caused by climate change means that old political norms may break down by extremist forces.[12] Thus, there can be no guarantee that LGBTQ people retain their protected social standing, which may, in turn, complicate efforts to recognize their refugee status when they are from what were previously considered ‘safe’ countries.[13]

The climate crisis exacerbates these issues by inflaming political controversy through the loss of dwindling resources. If LGBTQ people reside on the margins of society, it increases the chance that they will be denied access to these resources. Many LGBTQ communities report a higher rate of homelessness and poverty worldwide.[14] This trend particularly affects the transgender community, who often experience higher rates of hatred and violence, and may struggle to access jobs and affordable housing.[15] As countries experience a loss of wealth, LGBTQ people may be forced to flee to find better economic opportunities.[16] In particular, the violence they experience when accessing resources in an ever-diminishing market may trigger a need to leave what could have been a previously stable country. However, the framework of the Convention does not generally include economic migrants, and it is already difficult to prove that an LGBTQ person merits asylum when there is no direct evidence of political persecution.[17] The climate crisis may therefore raise barriers for LGBTQ people both economically and in terms of being able to adequately convey their need for asylum to officers.

This persecution is also intersectional. Climate change has a worse impact on females, with women being at higher risk of domestic violence and forced migration as the effects of climate change worsen.[18] Similarly, people of color are more likely to reside in areas facing a high rate of pollution or be at greater risk from health problems as a result of climate change.[19] LGBTQ people who exist within this spectrum therefore face multiple hurdles as they tackle the additional challenges posed by intersecting identities. From a refugee law perspective, it also makes it harder to have the LGBTQ aspect of their identity vindicated during the asylum process, as they may seek to confine themselves within the limited scope of the Convention. Gender, for example, is not automatically included under the definition of a refugee but is, like membership of the LGBTQ community, included under the ‘protected social group’ category.[20] This intersectionality means that an LGBTQ woman fleeing climate change focuses on the female aspect of her identity without being able to demonstrate how or why being LGBTQ also exacerbates these effects.[21]

Climate change could therefore heighten the nexus between persecution and identity, such that an LGBTQ person could partially rely on the climate crisis to obtain protection. It could also trigger persecution and a need to flee where none previously existed. However, as noted by Professors Goodwin-Gill and McAdam, it may prove difficult to tie the effects of climate change into persecution while maintaining the nexus between these effects and membership of a protected social group.[22] It is not that the political and economic repression of LGBTQ people would go unrecognized. Instead, there is a theoretical problem that fails to appreciate how these issues were caused by or worsened by the climate crisis.[23] If the cause of the persecution is not viewed holistically, then it is difficult for an asylum system to wholly encapsulate the individuality of the refugee, or the reasoning for justifying an asylum claim. This could, in turn, impact the capacity of the LGBTQ person to communicate how their identity worsened the impact of the instability generated by climate change. If climate change is only viewed in a ‘traditional’ manner (i.e., a focus on physical effects such as increased flooding), there is a risk that the unique difficulties experienced by LGBTQ people will go under-valued. Given how overlooked LGBTQ people often are in the grander scheme of refugee law,[24] climate change may render the compounding of their problems invisible amidst the wider deluge.

Part II: Teitiota v. New Zealand

The UN Human Rights Committee’s recent decision in Teitiota v. New Zealand[25] further indicates the difficulty of incorporating an intersectional perspective on LGBTQ refugees into the climate discourse. In Teitiota, the applicant attempted to halt his deportation back to Kiribati on the basis that the effects of climate change on the island posed a serious threat to life. This argument could have allowed the applicant to reside in New Zealand due to the Convention’s non-refoulement clause. The Human Rights Committee advised that, while it was possible for climate change-based displacement to trigger the non-refoulement clause, the applicant failed in his argument because there was no immediate threat to life.[26]

Of particular interest for this article is the emphasis the Human Rights Committee placed on the requirement that the risk posed by climate change ‘must be personal, that it cannot derive merely from the general conditions in the receiving state, except in the most extreme case.’[27] This requirement is problematic in the LGBTQ context when the decision of the New Zealand High Court (which the Superior Courts and the Human Rights Committee upheld) is examined.[28] Here, the High Court noted that the alleged persecution from climate change was ‘indiscriminate,’[29] and, as a consequence, could not fall within one of the five Convention grounds. In doing so, the Court did not acknowledge the particular vulnerabilities that marginalized people experience because of climate change. Professor Chhaya Bhardwaj correctly views this analysis as ‘surprising,’ given that refusal to allow the applicant to remain in New Zealand also affected his children,[30] whose generation is, per the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change, more likely to be adversely affected by climate change.[31]

The emphasis on human agency when considering persecution under the Convention also complicates LGBTQ climate refugee protection under the existing regime. The Committee asserted that, because the state still had the capacity to engage in ‘intervening acts’ before climate change devastated the island, the threat to life was not imminent.[32] Professor Simon Berhman points out that this ruling leaves states in a dilemma.[33] On the one hand, the state could act to mitigate climate change. However, this intervention is likely to be ineffective considering the limited resources possessed by an individual state, particularly those who struggle with poverty and inequality. In doing so, the state condemns its population to a rejection of refugee claims under the Convention. On the other hand, the state could refuse to act to prevent the worst effects of climate change. This non-intervention results in the eventual decimation of the state’s resources but raises the chance that its population can obtain refugee status. In either scenario, LGBTQ people and, in particular, female members of the LGBTQ community are among the most disadvantaged.[34] They are either likely to bear the brunt of the loss of resources as the state diverts its attention to climate change, or, as Balsari notes, experience the worst effects of the instability arising as a nation falls victim to environmental degradation.[35] These impacts are also gender sensitive, due to the traditional tendency for women to be more dependent on the natural resources of the land, as a result of the lack of broader economic opportunities within oppressive systems.[36] It can also be attributed to the wider trend within political systems in which women are one of the first groups to experience additional discrimination when there are social and cultural tensions caused by a loss of resources.[37]

The intersectional consequences of the Teitiota approach to climate refugees are more apparent when examined in the context of the high threshold set by the Human Rights Committee to demonstrate that there was a serious threat to life. The applicant was obliged to demonstrate that ‘the supply of fresh water [was] inaccessible, insufficient or unsafe’ and that he would be exposed to a ‘situation of indigence, deprivation of food, and extreme precarity’ to make a successful claim.[38] However, as Professor McAdam argues, this threshold is too high where a range of rights are impacted by environmental degradation.[39] In both the queer and female context, insufficient access to food and water could, as documented by Marina Andrijevic, contribute to a rise in domestic violence, or increase the likelihood of falling into poverty as patriarchal structures react to environmental challenges by removing economic opportunities from women and trans communities.[40] Gay men may also experience this backlash and be forced to conform with patriarchal standards by staying in the closet to avoid the backlash experienced by their more visibly vulnerable counterparts. Thus, not only is there a serious threat to life, but broader rights to equality, dignity, and liberty are also impeded.[41] The gender-blind attitude taken in Teitiota will make it difficult for courts to interpret similar cases in a manner that could account for these cumulative violations. If courts view climate change as affecting everyone equally, it is more difficult to justify why LGBTQ people are uniquely vulnerable to its effects. This perspective has consequences for any minority seeking to have their experiences incorporated within modern refugee frameworks.

While Justice Max Barrett correctly praises the Teitiota decision for not precluding a future claim based on the effects of climate change,[42] it does little to ameliorate concerns that the refugee framework ignores intersectional difficulties experienced by people who may be or will be fleeing the effects of climate change.

Part III: The Path Forward for LGBTQ Refugees and Climate Change

Our understanding of the intersection between the climate crisis and its impact on LGBTQ people is in its infancy. While climate refugees remain an unrecognized concept, there are several avenues asylum officers could take to ensure adequate protection of LGBTQ people caught up in the wider stream of migration.

Firstly, a broader interpretation of persecution will assist the general recognition of a climate refugee.[43] Climate inaction will be the central cause of worsening effects of climate change. These increased effects, in turn, will perpetuate social and economic inequity that is consistent with the oppression of LGBTQ people. It will either increase their likelihood of facing a backlash or decrease their ability to advance equality as the state devotes its time and resources to managing climate change-related chaos. Recognizing how and why the effects of climate change are human-oriented, and therefore in line with our perception of persecution, will be an important marker in vindicating climate refugees.[44] There will be a need for this broad lens as more climate refugees flee their homelands in search of safer territory.[45] This should eventually lead to a reckoning in terms of reforming the wider Convention, but for the moment, the broader scope of persecution proposed here may be a useful stop gap.

Secondly, there should be a rejection of the view that climate change is indiscriminate. It is evident, from both a science and policy perspective, that climate change will have a worse impact on women, LGBTQ people, and other marginalized groups. One way in which to reject this view is to adopt the suggestion of Professor McAdam that a ‘range’ of potential rights violations be examined when considering the impact of climate change.[46] A cumulative approach, as opposed to a strict threshold, would also assist LGBTQ refugees in meeting the harm element to the alleged threat posed by climate change.[47] This approach could draw on the broader cultural and social dynamics that contribute to the disadvantage experienced by LGBTQ people in society. This would mean that LGBTQ people at risk of climate change-driven persecution could have this persecution recognized through citing a range of particular rights they feel have been threatened by the increased effort to challenge their existence.[48] While this solution is imperfect, it is perhaps the most feasible method of recognizing intersectional concerns within the limited framework of the Convention, due to the avoidance of a political battle for wholescale reform.[49] It would also ensure some form of queer lens is present in climate refugee interpretation. Claimants would not only be focusing on the physical effects of climate change, but the resulting social pressure on them to conform with the norms of the devastated vulnerable community.

Conclusion:

The battle to recognize climate refugees will begin in earnest this decade as the effects of climate inaction come to roost. Those pursuing this goal must ensure that marginalized social groups can see their persecution understood and vindicated through protection. The effects of the climate crisis on the LGBTQ community have thus far been under-researched and under-appreciated. This article intends to shed some light on the future dangers to the LGBTQ community and demonstrate how these dangers could align with Convention interpretations. The Teitiota decision is clearly a pyrrhic victory for climate activists, but it should be built upon. The hope is that any foundation will prioritize feminist and queer lenses to create a nuanced perspective on the climate refugee.

* LL.M. Candidate at Harvard Law School.

[1] Edwin O. Abuya, Ulrike Krause, Lucy Mayblin, The Neglected Colonial Legacy of the 1951 Refugee Convention, 59 J. Int’l Migration 4 (2021).

[2] Teitiota v. New Zealand, UN Human Rights Committee, (2020).

[3] United Nations Refugee Agency, LGBTQI Persons, https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/lgbtiq-persons.html; Volker Türk, Ensuring Protection to LGBTI Persons of Concern, 25 Int’l J. Refugee 1 (2013).

[4] Annamari Vitikainen, LGBT Rights and Refugees: a Case for Prioritizing LGBT Status in Refugee Admissions, 13 Ethics & Glob. Pol. 1, 64 -78 (2020).

[5] Id.

[6] World Meteorological Organization, State of the Climate in Africa 2020 (WMO-No. 1275) (2021); IPCC, Sixth Assessment Report (2022); OECD, Poverty and Climate Change (2015); NW Arnell et al., The Global and Regional Impacts of Climate Change Under Representative Concentration Pathway Forcings and Shared Socioeconomic Pathway Socioeconomic Scenarios, 14 Env’t Rsch. Letters 8 (2019).

[7] S Nazrul Islam, Climate Change and Social Inequality, DESA Working Paper No. 152 (2017).

[8] Id.

[9] Suranjana Tewari, Pakistan Floods Put Pressure on Faltering Economy, BBC News (19th September 2022), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-62830771.

[10] Grame Reid, Global Trends in LGBT Rights During the Covid-19 Pandemic, Hum. Rts. Watch (2021); Graeme Reid, LGBTQ Inequality and Vulnerability in the Pandemic (2020); Hugo Greenhalgh, Religious Figures Blame LGBT+ People for Coronavirus, Reuters (2020).

[11] Id.

[12] Sellers S, Ebi KL, Hess J., Climate Change, Human Health, and Social Stability: Addressing Interlinkages, Environ Health Perspective; Von Uexkull, N., and Buhaug, H., Security Implications of Climate Change: A Decade of Scientific Progress, J. Peace Rsch., 58(1), 162–185, (2021).

[13] See The Williams Institute, LGBTQI+ Refugees and Asylum Seekers: A Review of Research and Data Needs (2022).

[14] The Williams Institute, LGBT People and Housing Affordability, Discrimination, and Homelessness (2020).

[15] United Nations Independent Expert on Protection Against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Human Rights of LGBT Persons (2021).

[16] Johannes Lukas Gartne, (In)credibly Queer: Sexuality-based Asylum in the European Union, Transatl. Persp. on Dipl. and Diversity (2015).

[17] Id.

[18] Phudoma Lama, Gendered Dimensions of Migration in Relation to Climate Change, Journal of Climate and Development (2021); Chindarkar, Gender and Climate Change-Induced Migration: Proposing a Framework for Analysis, Env’t Rsch. Letters (2012); Brockhaus, Is Adaptation to Climate Change Gender Neutral? Lessons from Communities Dependent on Livestock and Forests in Northern Mali, Int’l Forestry Rev. (2011).

[19] JD Kaufman, Confronting Environmental Racism, Env’t Health Persp. (2021).

[20] Alice Edwards, Transitioning Gender: Feminist Engagement with International Refugee Law and Policy 1950–2010, Refugee Surv. Q. (2010).

[21]Phudoma Lama, Gendered Dimensions of Migration in Relation to Climate Change, J. Climate and Dev. (2021).

[22] Guy Goodwin-Gill and Jane McAdam, The Refugee in International Law, 4th Edition, Oxford University Press, 2021, 644.

[23] Conor Cory, The LGBTQ Asylum Seeker: Particular Social Groups and Authentic Queer Identities, Geo. J. Gender l. (2019).

[24] Id.

[25] Teitiota v. New Zealand, UN Human Rights Committee, (2020).

[26] For a full overview of the case see Bhardwaj, C. (2021). Ioane Teitiota v. New Zealand (advance unedited version), CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016, UN Human Rights Committee, 7 January 2020. Env’t L. Rev., 23(3), 263–271.

[27] Teitiota v. New Zealand, UN Human Rights Committee, (2020).

[28] Teitiota v. The Chief Executive of the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment [2013] NZHC 3125.

[29] Id.

[30] Bhardwaj, C. (2021). Ioane Teitiota v. New Zealand (advance unedited version), CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016, UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), 7 January 2020. Env’t L. Rev., 23(3), 263–271.

[31] PCC, Sixth Assessment Report (2022).

[32] Teitiota v. New Zealand, UN Human Rights Committee, (2020).

[33] Simon Berhman, The Teitiota Case and the Limitations of the Human Rights Framework, Questions of Int’l l. (2020).

[34] Id.

[35] Satchit Balsari, Climate Change, Migration, and Civil Strife, Current Env’t Health Rep. (2020).

[36] UN Environment Program, Women and Natural Resources Unlocking the Peacebuilding Potential (2013).

[37] Id.

[38] Teitiota v. New Zealand, UN Human Rights Committee, (2020).

[39] Jane McAdam, Protecting People Displaced by the Impacts of Climate Change: The UN Human Rights Committee and the Principle of Non-refoulement, Am. J. Int’l L. (2020).

[40] Marina Andrijevic, Overcoming Gender Inequality for Climate Resilient Development, Nature Commc’n (2020).

[41] Christel Querton, Gender and the Boundaries of International Refugee Law: Beyond the Category of ‘Gender-Related Asylum Claims’,Netherlands Q. Hum. Rts. (2019).

[42] Justice Max Barrett, Climate Change Migration and the Views in Teitiota, Irish Jud. Stud. (2021).

[43] Jenny Han, Climate Change and International Law: A Case for Expanding the Definition of “Refugees” to Accommodate Climate Migrants, Ford. Undergraduate L. Rev. (2019).

[44] Joanna Apap, The Concept of ‘Climate Refugee’ Towards a Possible Definition, European Parliament Briefing (2019).

[45] Id.; UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Legal Considerations Regarding Claims for International Protection Made in the Context of the Adverse Effects of Climate Change and Disasters, 1 October 2020, https://www.refworld.org/docid/5f75f2734.html.

[46] Jane McAdam, Protecting People Displaced by the Impacts of Climate Change: The UN Human Rights Committee and the Principle of Non-refoulement, Am. J. Int’l L. (2020).

[47] Id.

[48] Olajumoke Haliso, Intersectionality and Durable Solutions for Refugee Women in Africa, J. Peacebuilding and Dev. (2016).

[49] Brienna Bagaric, Reforming the Approach to Political Opinion in The Refugee Convention, Ford. Int’l L. J. (2020).

Image Credit: Lauri Kosonen, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en.

Shared Responsibility: Building a Pathway to Justice for Missing Migrants and Their Families

ANGEL GABRIEL CABRERA SILVA*

Introduction

International human rights law was built on a straightforward legal assumption: that every human rights violation can be pinpointed as a single state’s responsibility. Grounded in a (now outdated) vision of state sovereignty, this doctrinal emphasis on “single-state” responsibility not only oversimplifies the socio-political reality of our times, but in certain circumstances, also imposes severe limitations on the prospects of justice.

The crisis of migrant disappearances sweeping through Central and North America highlights the increasingly evident limitations of this legal framework. As thousands of migrants go missing in transit to the United States, human rights has been a powerful language to mobilize a regional network of advocates. However, and perhaps ironically, human rights law has also proven to be largely insufficient as a tool for justice.

Drawing from my experience as a clinician, this article reflects on the mixed role that human rights play in this regional crisis. The first part summarizes the background context. The second part sheds light on how the emphasis that human rights puts on the model of “single-state” responsibility imposes practical limitations on migrants’ struggles for justice. The third part spotlights an emergent solution; it describes how the legal strategies pursued by collectives of families of Central American migrants are challenging these limits and pushing human rights towards a perspective based on “shared responsibility.” This reformulated perspective is opening a pathway for justice and delivering important lessons for the broader human rights ecosystem.

1. The Regional Crisis of Migrants’ Disappearances

On May 1, 2022, a group of 49 Central American women crossed the border between Mexico and Guatemala.[1] Unlike most of their compatriots, they were bound not to the United States but to Mexico City. The women were taking part in the “XVI Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants,” a symbolic event organized every year by the Mesoamerican Migrant Movement to demand justice for the thousands of Central American migrants that have gone missing in their transit to the United States.[2] This year, the caravan represented the struggle of various collectives of Central American families that are still searching for over 2,000 of their missing sons and daughters.[3] That number does not include all cases of missing migrants, but is already higher than the 1,800 cases of missing foreigners reported by Mexican authorities.[4]

The struggle of those women is sadly inserted in a human rights crisis of even greater proportions. Over the last decade, more than 75,000 migrants have gone missing along the corridor that connects Central America, Mexico, and the United States.[5] This figure includes Mexicans, Central Americans, and persons from other countries that have perished or vanished somewhere along the journey north—most of them in Mexico, but also many within the United States. Statistics are by their nature imperfect, but evidence collected by civil society groups suggests that migrants disappear or go missing because they fall victim to criminal organizations, police abuse, or the harshness of the route.[6] What all these migrants have in common is that they are all persons who left their homes hoping to find a better future, but would neither get there nor ever return home.

The regional crisis of missing migrants has an incommensurable human toll on every victim and his or her family. However, its effects are especially harsh when a migrant disappears outside his country of origin. In those situations, the families must grieve the loss of a loved one and, at the same time, they must confront all the migratory and administrative hurdles of trying to access the justice systems of foreign countries—from obtaining a visa to demonstrating their legal standing as relatives of a victim. In the case of Central American families, actions as simple as reporting a disappearance in Mexico or filing a judicial claim in the United States turn into onerous endeavours. More complicated tasks like participating in the search of a missing migrant, inquiring about the status of an investigation, requesting reparations, or even repatriating any mortal remains become extremely complex to complete.

Over the years, civil society groups have denounced and documented the difficulties that migrant’s families face in their pursuit for justice. In Central America, groups of families have organized through various “Colectivos de Familiares” (like COFAMIDE, COFAMIGUA, and many others) to put the issue under the international spotlight.[7] Additionally, non-governmental organizations have established networks to facilitate families’ transnational access to state institutions.[8] International bodies have documented patterns in the disappearances of migrants and failures in state policies.[9] And even academic institutions have made efforts to support the forensic identification of migrant remains and to diagnose the structural bases of the problem.[10]

However, the challenge persists, and the families of missing Central American migrants are still fighting an uphill battle simply to have access to justice. The obstacles that these families confront due to deficient inter-state cooperation then are compounded with the multiple flaws that already hamper the performance of national institutions charged with investigating disappearances. Many of the relatives of missing migrants are thus forced to embark on their own transnational odyssey: this time not to seek a better future, but to pursue justice.

2. Limits of Human Rights Law

Scholars have criticized human rights law for many reasons including its state-centric vision,[11] ideological imperialism,[12] reductive discourses,[13] and tendency to individualize claims.[14] However, the dire situation of families of missing Central American migrants sheds light on another problematic—yet under-analyzed—limit imposed by human rights norms, the doctrinal requirement to pinpoint a specific human rights violation as the individual responsibility of a particular state. Let me briefly summarize the implications of this model of legal reasoning based on “single-state” responsibility.

Under international human rights law, every person has the right to be protected against enforced disappearances.[15] If an enforced disappearance occurs, the victim’s family has a right to truth, justice, and reparations.[16] These standards apply to every state that has ratified the relevant human rights treaties—which arguably includes all states involved in the Central and North American crisis.[17]

Correspondingly, international human rights law establishes rules to determine which state shall bear the responsibility for the realization of all these rights. In the case of enforced disappearances, the primary determinant of responsibility is territorial control.[18] Generally, the state where the disappearance took place is the one responsible for guaranteeing the rights of migrants and their families.[19] Within the regional crisis of missing migrants, this means that either Mexico or the U.S. would hold primary responsibility towards most families of Central American migrants—as most disappearances occur within their borders.

Allocating the primary legal responsibility to the country where a migrant went missing is quite problematic. The transnational nature of the crisis implies that no individual state can meet its obligations to missing migrants on its own. Without coordination with Central American authorities, it is extremely hard for Mexico or the U.S. to procure the necessary evidence to conduct an adequate investigation, perform the identification procedure required to repatriate migrant remains, or communicate with families entitled to reparations. In fact, without regional coordination, neither Mexico nor the U.S. can even receive reports of potential disappearances from relatives of migrants who stayed back home.[20]

The mismatch between human rights law and the complexity of the migration crisis creates some perverse incentives. On the one hand, Central American governments could avoid their responsibilities to missing migrants by simply deflecting claims to their northern neighbors. On the other hand, Mexico and the United States could blame their inefficiency in handling the crisis to the challenges of inter-state cooperation.

Civil society organizations have made great efforts to avoid these pitfalls by fostering deeper inter-state coordination. Their strategies have been quite consequential. In 2015, for example, civil society advocacy led to the creation of the Mexican “Mecanismo de Apoyo al Exterior” (Mechanism for Foreign Support or MAE), an inter-institutional policy established by the Mexican government.[21] The MAE is an unprecedented initiative that aims to offer a solution for families of Central American migrants who have disappeared in Mexico. At its core, the policy aims to use Mexican consulates in Central America as conveyors, to receive reports of migrants that disappeared in Mexico and then transmit the results of investigatory efforts back to the families. In this way, families in Central America can access the Mexican justice system without having to leave their own countries. Additionally, the MAE also strives to facilitate coordination between families in Central America and the complex ensemble of Mexican authorities in charge of searching missing migrants, investigating disappearances, and providing reparations.

The MAE has been formally operating for over half a decade now, but its practical implementation is still incomplete and deficient in many ways.[22] During this time, the improvement of the MAE has become a tactical priority in the agenda of the regional movement for migrants’ rights. One key part of the ongoing improvement efforts seeks to enhance the performance of Mexican institutions involved with the MAE (especially the Mexican consulates and prosecutor’s office). However, another part of ongoing efforts to improve the MAE is to push Central American States to take a more proactive approach to the mechanism. The MAE can hardly succeed if Central American governments do not—at the very least—ensure that migrants’ families know of the MAE’s existence, are able to travel to the cities where Mexican consulates are located and are capable of obtaining technical advice to use the mechanism.

It is at this point where the model of “single-state” responsibility threatens to become increasingly problematic. Even if the MAE has planted the seeds for an unprecedented form of transnational cooperation, civil society efforts to improve its implementation must confront the predominant logic embedded in human rights law. The current logic creates the risk that if Central American states fail to engage adequately with the MAE, they can still squeeze out of formal human rights responsibility. Advocates could denounce recalcitrant states for violating basic moral principles or even for running against general principles of international cooperation.[23] However, at the end of the day, under the formalistic logic of human rights law, the responsibility for migrants who disappear in Mexico would fall upon Mexico, and Mexico alone.

3. Building a Way Forward: A Vision of Shared Responsibility

From a strictly doctrinal perspective, the limitations imposed by human rights law often appear unescapable. However, socio-legal literature abounds with examples of social mobilizations that have been able to deploy human rights norms in innovative ways.[24] The Central American movement for migrants’ rights is a clear example of how advocates can overcome these obstacles. A few years ago, civil society organizations launched an advocacy strategy that is outmaneuvering the doctrinal emphasis on single-state responsibility. While the process is still ongoing, if successful, it may very well create an institutionalized model of shared responsibility around the MAE.

Back in January 2021, a group of family collectives (with the support of the Fundación para la Justicia y el Estado de Derecho and Boston University’s Human Rights Clinic) filed a General Allegation before the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID).[25] Established in 1980, the WGEID is one of the earliest special procedures created by the United Nations Human Rights Commission—now the UN Human Rights Council.[26] The General Allegation procedure is a non-judicial mechanism intended to alert states to obstacles in the implementation of the “Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance” (the Declaration).[27] The General Allegation mechanism is activated when civil society groups approach the WGEID to denounce situations where the rights protected by the Declaration are being violated. After the reliability of the sources is confirmed, the WGEID transmits the information to the concerned state and typically requests further information.[28] Subsequently, after a state submits its responses to the General Allegation, the WGEID can decide to keep monitoring the situation and assist that individual state to comply with their duties under the Declaration.

Even if the mechanism itself is anything but new, the strategy advanced by this civil society group incorporated two very innovative aspects. The first ground-breaking feature is that the General Allegation was effectively introduced against multiple states. In this case, the civil society coalition denounced all states involved in the regional crisis.[29] To my knowledge, this was one the first occasions in which the WGEID transmitted the submission to multiple states at the same time (Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Mexico).[30]

The second innovative characteristic of this legal strategy lies in the way it is framed around a transnational solution. Typically, General Allegations are used to denounce violations of human rights. However, the submission went a step beyond that. Besides denouncing the severity of the regional crisis of migrants’ disappearances, it also showcased the potential of the MAE to build a solution and documented the various obstacles that hinder this potential— especially the lack of inter-state coordination.

In this way, the advocacy strategy stands out, not only because it engages all States involved in the regional crisis, but because it does so through the lens of their shared responsibility in building a particular solution (namely the MAE). By stepping beyond a simple denunciation of the crisis itself, this framing avoids falling into the single-state model of allocating responsibility on the basis of territorial jurisdiction. In other words, putting the MAE at the center of the conversation means that the degree of responsibility of a particular state within a pattern of migrants’ disappearances becomes less relevant than the collective responsibility of all States to implement a transnational solution.

Today, this strategy is still developing. After its submission in early 2021, the WGEID transmitted the General Allegation to the States involved—who then were given the opportunity to provide a response and submit information. As is true with many international mechanisms, the procedural delays are lengthy. Knowing that it would take a while to process their submission, family collectives and their NGO allies continued to advocate for the gradual improvement of the MAE. A notable effort came in October of 2021, during a recent visit of the UN Committee on Enforced Disappearances to Mexico, where Central American families were able to highlight the situation of missing migrants as a pressing issue within Mexico’s titanic crisis of disappearances.[31]

However, last January 2023 marked the second anniversary of the General Allegation. During these two years, the civil society coalition prepared a follow-up submission that took another step in their advocacy before the WGEID. This submission emphasizes the need for the WGEID to get more closely involved in monitoring the MAE’s performance. According to its mandate, the WGEID can “provide appropriate assistance in the implementation by States of the Declaration.”[32] Given that the crisis of migrant’s disappearances is ongoing and that the MAE’s implementation remains deficient, the hope is that the WGEID will exercise its mandate to “assist” States more proactively to help create the transnational coordination required to realize the MAE’s full potential.

Naturally, this legal strategy is full of uncertainty—as most innovative strategies are. However, in its first submission, the civil society coalition has already suggested one way forward. The coalition requested the WGEID to conduct a sequence of country-visits to monitor the way each State engages with the MAE in order to recommend coordinated actions to improve its performance.[33] Another potentially effective action would be for the WGEID to become a convening authority that brings representatives of each state and civil society together to deliberate about how best to implement the MAE. However, even for this author, it is unclear what form such proactive measures could (or should) take in practice. The only thing that seems certain is that an ideal solution would require a significant degree of creativity and an openness to experimentation.

Conclusion

It is not an overstatement to say that we live in troubled times. The struggle of the families of Central American migrants is just one among many others transnational social movements who are engaged in and are vying to open new ways forward for the protection of migrant’s rights. In the current global context, the innovative strategy before the WGEID not only holds the potential to advance a solution to this specific crisis but could also inspire other transformative actions.

We can learn two main lessons from the legal struggle of Central American families around the MAE. The first lesson is that human rights strategies need not subscribe to the “single-state” mode of responsibility that prevails in human rights doctrine. As the struggle of these families shows, when such framing becomes an obstacle for justice, activists can strive to articulate their claims in ways that foreground the “shared responsibility” of various states.

The second lesson is the possibility (and importance) of recognizing that the existing framework of human rights institutions is not a fixed set of rules and mechanisms, but an institutional edifice that can be updated—even if only gradually—without the need for formal legal reform. The WGEID is a decades-old human rights body, and yet a regional movement of migrants’ families conceived a strategy that aims to repurpose its procedures so that the institution can rise to the challenge presented by the regional crisis.

The ultimate outcome of the strategy is yet to be seen. However, whatever the future may bring, these lessons can inform struggles in other areas. Across the globe, human rights crises are becoming increasingly too complex to tackle through the strict lenses of mainstream human rights legal doctrine. Climate change, social inequality, and the ever-growing flows of migrants and refugees are challenges with transnational and collective dimensions that demand creative thinking, transnational action, and a whole lot of strategic savvy.

[*] SJD Candidate; LLM’16 Harvard Law School; LL.B. Universidad de Guadalajara. Former Clinical Instructor at Boston University’s International Human Rights Clinic (2021-22). This article was inspired through collaborating with clinical colleagues Susan Akram and Yoana Kuzmova, our partner in Central America, Claudia Interiano and our team of excellent clinical students Rachel Medara, Katherine Grisham and David Andreu. I would also like to thank Susan Akram for her comments to this article and Lloyd Lyall for his help during the editing process. All flaws are my own. The author thanks the University of Guadalajara for its support.

[1] ‘Marcha de Madres Centroamericanas’ Busca an sus Hijos en Mexico, Deutsche Welle (May 8, 2022), https://perma.cc/BHV3-C8AN (last visited Dec. 14, 2022).

[2] Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants Kick Off a Global Migration Search Movement, UN News, Nov. 6, 2018, https://perma.cc/5QL6-SBYB (last visited Dec. 14, 2022).

[3] Caravan of Central American Mothers Resumes Search for their Missing Children in Mexico, Pledge Times (May 2, 2022), https://perma.cc/CY48-GX4E (last visited Dec. 14, 2022).