Ideological Leanings in Likely Pro Bono Biglaw Amicus Briefs in the United States Supreme Court – Derek T. Muller

Ideological Leanings in Likely Pro Bono Biglaw Amicus Briefs in the United States Supreme Court

Derek T. Muller*

Each term, the United States Supreme Court receives hundreds of amicus briefs filed in merits docket cases. These totals have increased over the years,[1] and these briefs have found increasing influence in front of the Court.[2] Many of the largest law firms file amicus briefs before the United States Supreme Court.[3] These amicus briefs are often pro bono, which means the clients do not pay for the firm to file the brief.[4] That pro bono work can quickly total millions of dollars of legal briefing subsidized by the law firm.[5] And pro bono work often reflects the law firm’s desire to work for its prior commitments to what it identifies as the “public good.”[6]

Controversies have arisen in recent years over ideological rifts in America’s largest law firms, sometimes for attorneys representing politically unpopular clients,[7] at other times for publicly articulating politically unpopular positions.[8] The ideological leanings of the largest law firms have been a topic of lively debate.

Some efforts have been made to evaluate law firm partisanship based on the political contributions of their attorneys or employees.[9] Such efforts have their own limitations and complexities, so it is worth considering other ways to examine the political leanings of law firms. This Article offers a different approach. It examines the ideological leanings of pro bono work of the largest law firms.

By focusing on pro bono amicus briefs, this Article focuses on the most discretionary aspects of legal practice. Pro bono reflects the choices of attorneys to invest time and resources into a case. The American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct encourage attorneys to provide at least 50 hours of pro bono work each year.[10] A great deal of pro bono work may have no particular ideological valence—indeed, the ABA encourages pro bono work for “persons of limited means.”[11] But some work may have an ideological valence. And large law firms must approve attorneys’ choices, which can reflect the firms’ priorities, too. Filing an amicus brief can consume substantial resources at the law firm—the law firm is putting its significant financial backing behind the effort.[12]

Rather than representing a client as an adversarial party in the case, or being compensated by a paid client, the firm opts to use its valuable resources to assist others at no cost to the client, and to have a voice in litigation where the client is not a party to the dispute but has an interest in the outcome. Cases before the Supreme Court have the highest profile and can affect significant policy in the United States. It offers one way to examine the commitments of law firms.

Data Collection

I developed a novel dataset for all Supreme Court merits cases from October Term 2018 to October Term 2021, a four-year period. I collected 3280 amicus briefs filed on merits cases in that period.[13]

There are admitted limitations. This data does not include cases where amicus briefs were filed at the certiorari stage where the Supreme Court declined to hear the case,[14] or in “emergency docket” cases where the Court may issue significant decisions without a full merits briefing and oral argument.[15] Amicus practice also extends to state courts and lower federal courts; this Article only focuses on one slice of litigation, albeit the highest profile litigation—cases before the Supreme Court. And this Article only focuses on the largest firms—many large firms, smaller firms, boutique firms, and public interest organizations file briefs.

The dataset coded each case using the Supreme Court Database at Washington University for “liberal” or “conservative.”[16] This methodology has its own documented limitations and is of course reductionist given the complicated issues that can attend any case,[17] but it allows for a ready reference to an established dataset.[18] I then compared all amicus briefs filed in those cases to determine whether they supported the “liberal” or “conservative” side. There is a limitation to taking the ideology of “liberal” or “conservative” in briefing and translating it ideologically in firms. It is possible, of course, that one’s political preferences do not necessarily perfectly overlap with these ideological legal positions. That said, the reason I chose to examine amicus briefs—those cases where parties volunteered to make their positions known to the court—is because it is more likely that it reflects ideological preferences.

I focused on “Biglaw,” here defined as the American Lawyer 100 (“Am Law 100”)—the top 100 law firms in the United States by gross revenue measured in 2021.[19] Nearly every one of the top 100 firms filed at least one amicus brief before the United States Supreme Court in the October 2018 to October 2021 terms (cases decided between October 1, 2018 and June 30, 2022). Occasionally, two Am Law 100 firms joined on the same brief. In those cases, I coded both Am Law 100 firms.[20]

Overall Results

Of the 3280 amicus briefs filed in this period, the Am Law 100 firms signed onto 928 amicus briefs. But amicus briefs may be on behalf of paying clients or on behalf of pro bono clients. For pro bono clients, there is greater flexibility, discretion, and selectivity—which means it can offer insight into the firm’s priorities. It can represent a contribution of time and money that the firm is willing to make on behalf of a client in pursuit of a particular outcome in a particular case.[21]

I examined whether the firm represented what I labeled a “likely pro bono” client. Firms typically do not disclose the fee arrangements with clients, although there are occasional publicized exceptions.[22] So this Article creates a proxy for clients who are “likely pro bono.” These clients included several groups: non-profit or not-for-profit organizations; current or former government officials; professors and scholars; professionals, such as scientific experts, chaplains, prison guards, and immigration officials; and survivors or victims. It is likely that this is overinclusive, by adding non-profits who may be paying clients of the firm;[23] and it is possibly underinclusive, as there might be for-profit corporations or other individuals who have firms representing them pro bono. It is also possible that law firms provide discounted rates for some non-profits instead of pro bono services.

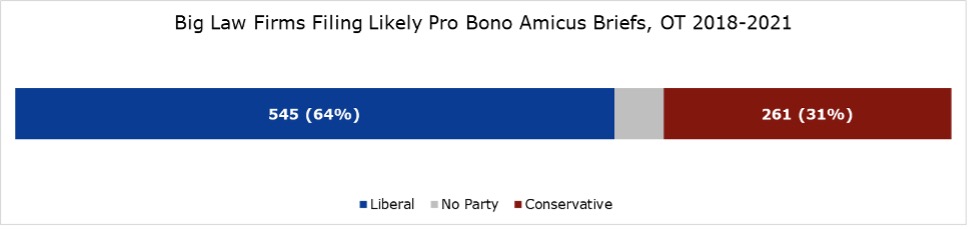

Most law firms filed amicus briefs—851 briefs in total—that fit this “likely pro bono” category. Of these, 545 (64%) aligned with the liberal position, 261 (31%) with the conservative position, and 45 in support of neither party. See Figure 1.

Figure 1

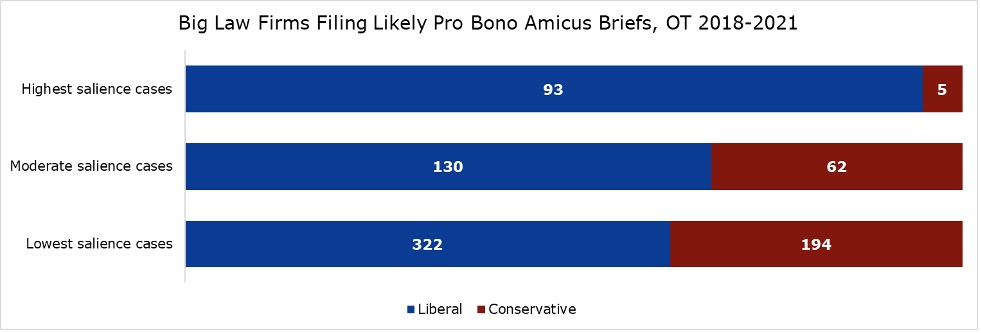

Figure 1 includes all cases, but not all cases are alike. The Supreme Court decides dozens of cases each year, but different cases attract different levels of attention. In the 223 cases with at least one amicus brief filed, the median was 10 briefs filed.[24] The mean was 14.7 and the standard deviation was 16.4.[25]

Some have more public or legal significance or salience than others. There are a variety of ways to consider salience.[26] For this Article’s purposes, I look at amicus briefs filed in relation to other amicus briefs—the more briefs, the higher the salience.[27] I created three cohorts of amicus briefs. The first are those with the “lowest salience,” with fewer than 30 amicus briefs filed. The second are those in “moderate salience” cases, those with at least 30 but fewer than 60 amicus briefs amicus briefs filed (around one and three standard deviations above the mean). The final category are the “highest salience” cases, those with at least 60 amicus briefs filed (around three standard deviations above the mean). The terminology of “salience” is an imperfect one, as cases have salience or significance for any number of reasons regardless of the volume of amicus briefs filed, but for my purposes it is a way of determining cases more “popular” among amicus briefs filed generally—a proxy, however imperfect, for significance, actual or perceived. Any line-drawing is admittedly subject to a certain degree of arbitrariness.

Most cases fit the “lowest salience” cohort—201 of the 223. In those lowest salience cases, Biglaw firms signed onto 526 briefs in support of liberal or conservative positions. (I removed the briefs in support of neither party for this and subsequent analysis.) The briefs in the “lowest salience” cohort were fairly evenly distributed—322 in support of liberal positions (62.4%) and 194 in support of conservative positions (37.6%).

In “moderate salience” cases—17 cases—the briefs skewed a bit more toward the liberal position. In 192 briefs signed onto by Biglaw firms in moderate salience cases, 130 were in support of the liberal position (67.7%), and 62 in support of the conservative position (32.3%).

And just five cases fit the “highest salience” profile: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization[28] (131 briefs); Bostock v. Clayton County and Harris Funeral Homes v. EECO[29] (93); New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Bruen[30] (81); Fulton v. City of Philadelphia[31] (80); June Medical Services v. Russo[32] (69). Two cases were about abortion, two about sexual orientation or gender identity (one of which included a religious liberty issue), and one about the Second Amendment. These “highest salience” cases touch on some of the most divisive areas of political controversy. Ninety-eight amicus briefs were filed in these five cases by fifty Biglaw firms. Ninety-three briefs (94.9%) aligned with the liberal position, and five (5.1%) with the conservative position. While there is a larger amount of ideological diversity among the less salient cases, in these five “highest salience” cases, the briefs skewed heavily in one direction.[33] For the comparison of the three cohorts of “salience,” see Figure 2.

Figure 2

Firm Specific Results

In a short period of time (just four years and 223 cases with amicus briefs), it can be difficult to identify trends for individual law firms. But I attempted to identify preliminary trends (again excluding amicus briefs filed in support of neither party).

First, I pulled the firms that filed 10 or more amicus briefs on behalf of liberal positions for likely pro bono clients (here, 16 firms):

Figure 3

| Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher | 34 |

| WilmerHale | 30 |

| Sidley Austin | 27 |

| Jenner & Block | 25 |

| O’Melveny & Myers | 24 |

| Covington & Burling | 22 |

| Hogan Lovells | 19 |

| Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe | 16 |

| Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer | 15 |

| Mayer Brown | 14 |

| Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison | 13 |

| Jones Day | 12 |

| Latham & Watkins | 12 |

| Davis Wright Tremaine | 11 |

| Cooley | 10 |

| McDermott Will & Emery | 10 |

Second, I examined the firms that filed 10 or more amicus briefs on behalf of conservative positions for likely pro bono clients (here, five firms):

Figure 4

| Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher | 19 |

| Mayer Brown | 18 |

| Sidley Austin | 11 |

| Jones Day | 11 |

| Baker Botts | 10 |

Sixteen firms filed at least 10 amicus briefs in support of liberal positions; just five filed at least 10 in support of conservative positions. And four of the five firms on the conservative list also appear on the liberal list.

If we expect firms to have a coherent and consistent ideological preference, we might expect firms to lean overwhelmingly in one direction or another. But many firms appear on both lists. Perhaps, however, this is unsurprising—the firms with the largest Supreme Court amicus practices simply have the most opportunities to engage in appellate amicus practice, and many opportunities arise regardless of ideology.

Relatedly, I decided to look the distribution among firms that filed at least 10 amicus briefs on behalf of likely pro bono clients in this period—29 firms in all. See Figure 5.

Figure 5

| Amicus Briefs by Ideology (at least 10 filed, OT 2018-2021) | |||

| Firm | Liberal Briefs | Conservative Briefs | Pct Liberal |

| Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison | 13 | 0 | 100% |

| Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe | 16 | 1 | 94% |

| O’Melveny & Myers | 24 | 3 | 89% |

| Davis Wright Tremaine | 11 | 2 | 85% |

| McDermott Will & Emery | 10 | 2 | 83% |

| Perkins Coie | 9 | 2 | 82% |

| WilmerHale | 30 | 7 | 81% |

| Latham & Watkins | 12 | 3 | 80% |

| Morrison & Foerster | 8 | 2 | 80% |

| Ropes & Gray | 8 | 2 | 80% |

| Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer | 15 | 4 | 79% |

| Hogan Lovells | 19 | 6 | 76% |

| Jenner & Block | 25 | 9 | 74% |

| Covington & Burling | 22 | 8 | 73% |

| Sidley Austin | 27 | 11 | 71% |

| Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld | 7 | 3 | 70% |

| Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom | 7 | 3 | 70% |

| Cooley | 10 | 5 | 67% |

| Kirkland & Ellis | 9 | 5 | 64% |

| Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher | 34 | 19 | 64% |

| Dechert | 7 | 4 | 64% |

| Goodwin Procter | 9 | 6 | 60% |

| Greenberg Traurig | 6 | 4 | 60% |

| Baker & Hostetler | 7 | 6 | 54% |

| Jones Day | 12 | 11 | 52% |

| Foley & Lardner | 5 | 5 | 50% |

| Mayer Brown | 14 | 18 | 44% |

| Baker Botts | 6 | 10 | 38% |

| Troutman Pepper | 3 | 8 | 27% |

There is a fairly broad spread across these firms. Only three filed more amicus briefs in likely pro bono cases for conservative positions over liberal positions, and most firms fall on the liberal side of the 50% divide. But most firms filed at least 25% of amicus briefs in support of conservative positions. And several firms filed overwhelmingly in support of liberal positions. It shows some variance among firms in terms of the kinds of likely pro bono amicus work they engage in.

Finally, I examined the five “highest salience” cases. Recall that these cases had the strongest ideological polarization, with Biglaw overwhelmingly favoring the liberal positions in these cases. Fifty Biglaw firms filed amicus briefs on behalf of likely pro bono clients in these cases. Forty-six filed in support of the liberal position in at least one case, and four in support of the conservative position in at least one case. Zero firms filed on behalf of both a conservative position and a liberal position across these five cases. There was more ideological polarization in these cases. That is admittedly harder to measure, given how many firms only filed one or two briefs in a set of five cases. But a consistent pattern did emerge across the firms of filing on the liberal side. See Figure 6.

Figure 6

| Likely pro bono amicus briefs filed in five “very significant” cases | Liberal | Conservative |

| 5 briefs | Covington & Burling

Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel WilmerHale |

none |

| 4 briefs | Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer

Hogan Lovells Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe |

none |

| 3 briefs | Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton

Crowell & Moring Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher Jenner & Block Morrison & Foerster Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom |

none |

| 2 briefs | Cooley

Cravath, Swaine & Moore Duane Morris Fried Frank Goodwin Procter Latham & Watkins Mayer Brown Milbank Perkins Coie Ropes & Gray Simpson Thacher & Bartlett Willkie Farr & Gallagher |

Foley & Lardner |

| 1 brief | Akerman

Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld Baker McKenzie Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner Cozen O’Connor Davis Polk & Wardwell Davis Wright Tremaine Debevoise & Plimpton Dechert Greenberg Traurig Husch Blackwell K&L Gates McDermott Will & Emery O’Melveny & Myers Paul Hastings Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan Shearman & Sterling Sidley Austin Squire Patton Boggs Weil, Gotshal & Manges |

Hunton Andrews Kurth

McGuireWoods Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough |

Limitations, Implications, and Areas for Future Inquiry

There are limitations to conclusions one may draw from these figures, and a variety of questions about causation. For law firms, it does not tell us about cases where an attorney at a firm wanted to file a brief, but a conflicts check found a difficulty. A firm that has a partner who has long represented a major non-profit in pro bono work in Supreme Court briefs is likely to continue to do so when similar cases arise, and it can lead to a set of similar ideological briefs being filed without an opportunity for someone else at the firm to weigh in on the other side. This may be particularly true in the “highest salience” cases, where representing one position in, say, an abortion dispute in the past likely results in similar positions in the future. That said, it may reflect a reluctance to abandon a position previously staked or a pro bono client previously taken on.

It also cannot tell us about rejections of requests from attorneys to file an amicus brief—whether it was a decision of resources and time, or a decision that the firm did not support the underlying position. Another reason for rejection may well be client preferences. Firms may choose positions in amicus briefs that signal support for a particular cause, or refuse to take positions elsewhere, to appease clients.[34]

Even claiming that “the firm” has a position can be misleading, as it may well be a decision of the committee that clears such requests, and it may well reflect the preferences of the committee more than the firm as a whole. And it may be that partners or associates at the firm are not requesting the work for a particular ideological position in the first place, as opposed to having their requests denied for one reason or another. That said, a fruitful area of future research might try to compare political contributions at law firms with the ideological preferences of likely pro bono amicus briefs.[35] Similarly, a look at individual Supreme Court litigators at these firms and their previous ideological or partisan affiliations may be useful.

Relatedly, it is possible that some conservative-leaning pro bono organizations do not request Biglaw firms to join briefs, particularly in high salience cases, because they anticipate the answer will be no. Or perhaps there are fewer conservative-leaning than liberal-leaning groups out there who are interested in such briefs. Or some pro bono organizations may prefer to file on their own, if they have attorneys in-house who prefer to be named as the attorney of record on brief and maintain control of the brief. That decision, of course, loses the signaling mechanism of an elite law firm’s name on a brief.[36] And it is possible that groups supporting liberal-leaning positions are better at coordinating amicus brief activity than groups supporting conservative-leaning positions.[37] A qualitative analysis of the non-profit organizations that file amicus briefs may be illuminating.

For all its limitations, this Article does offer some insight into likely pro bono amicus work at large law firms. There is little doubt that America’s largest law firms invest more resources in more liberal-leaning causes than conservative-leaning causes on behalf of likely pro bono clients in front of the United States Supreme Court.[38] But they invest substantial resources into conservative-leaning causes, too. In the biggest cases of this recent four-year period, however, the firms’ likely pro bono amicus work overwhelmingly leaned in the liberal direction.[39]

That said, there is some meaningful ideological diversity even within a firm in likely pro bono amicus briefs. It may show that political donations are only one measure—and an imperfect measure—of ideology within a law firm, either among the attorneys at the firm or as a signal for the firm’s clients.[40] And there is also some diversity across firms—a few firms leaned more conservative in this time period, some firms had a more even split, and most others leaned somewhat heavily toward liberal positions. The data also presents a more complicated portrait of law firms that may be publicly portrayed through a particular ideological or partisan lens. The data shows a variety of ways in which the largest law firms are putting their time and resources in litigation before the United States Supreme Court, and some diversity among law firms’ approach to amicus briefs on behalf of likely pro bono clients.

* Professor of Law, Notre Dame Law School. Special thanks to Adam Feldman, Andy Hessick, and Kyle Rozema for feedback on earlier drafts of this piece.

[1] See, e.g., Joseph D. Kearney & Thomas W. Merrill, The Influence of Amicus Curiae Briefs on the United States Supreme Court, 148 U. PA. L. Rev. 743 (2000).

[2] Allison Orr Larsen & Neal Devins, The Amicus Machine, 102 Va. L. Rev. 1901 (2016); Paul M. Collins, Jr., Pamela C. Corley, & Jesse Hamner, The Influence of Amicus Curiae Briefs on U.S. Supreme Court Opinion Content, 49 L. & Soc. Rev. 917 (2015).

[3] See, e.g., H.W. Perry Jr., The Elitification of the U.S. Supreme Court and Appellate Lawyering, 72 S.C. L. Rev. 245, 262–63 (2020); Larsen & Devins, supra note 2, at 1906–07, 1916–17, 1927–30.

[4] See Larsen & Davis, supra note 2, at 1918, 1929–31. See also Nancy Morawetz, Counterbalancing Distorted Incentives in Supreme Court Pro Bono Practice: Recommendations for the New Supreme Court Pro Bono Bar and Public Interest Practice Communities, 86 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 131 (2011).

[5] See infra note 12.

[6] See, e.g., Pro Bono, Morgan Lewis, https://www.morganlewis.com/our-firm/our-culture/pro-bono (last visited Jan. 5, 2024) (“Our firm’s commitment to doing work for the public good manifests through the pro bono efforts of lawyers in every one of our global offices. We take on matters impacting individuals or small groups as well as litigation driving large-scale societal change.”); Pro Bono, Arnold & Porter, https://www.arnoldporter.com/en/about/pro-bono (last visited Jan. 5, 2024) (“We have a long history of taking on matters to redress injustice . . . . The broad spectrum of pro bono work we undertake is driven by our dedication to amplifying the voices of those who might not otherwise be heard.”); Pro Bono, Cleary Gottlieb, https://www.clearygottlieb.com/practice-landing/pro-bono (last visited Jan. 5, 2024) (“Founded in a spirit of inclusiveness, personal and professional responsibility, compassion for the needs of others, and dedication to improving the communities in which we live and work, Cleary Gottlieb is fully committed to the duties of good global citizenship. We believe pro bono work should be a mindful choice, one that expresses both personal and collective interests.”).

[7] See, e.g., Marisa M. Kashino, Clement Praised by Peers for Leaving King & Spalding Over DOMA, Washingtonian, Apr. 25, 2011, https://www.washingtonian.com/2011/04/25/clement-praised-by-peers-for-leaving-king-spalding-over-doma/; David Lat, Paul Clement Leaves Kirkland & Ellis Amid a Dispute Over Gun Cases, Original Jurisdiction, June 24, 2022, https://davidlat.substack.com/p/paul-clement-leaves-kirkland-and.

[8] See, e.g., David Lat, Biglaw’s Latest Cancel-Culture Controversy, Original Jurisdiction, Dec. 1, 2022, https://davidlat.substack.com/p/biglaws-latest-cancel-culture-controversy.

[9] See, e.g., Derek T. Muller, Ranking the most liberal and conservative law firms, Excess of Democracy, July 16, 2013, https://excessofdemocracy.com/blog/2013/7/ranking-the-most-liberal-and-conservative-law-firms; Adam Bonica, Adam S. Chilton, & Maya Sen, The Political Ideologies of American Lawyers, 8 J. of L. Analysis 277 (2016); Derek T. Muller, Ranking the most liberal and conservative law firms among the top 140, 2021 edition, Excess of Democracy, Nov. 8, 2021, https://excessofdemocracy.com/blog/2021/11/ranking-the-most-liberal-and-conservative-law-firms-among-the-top-140-2021-edition.

[10] Model Rules of Pro. Conduct r. 6.1. (Am. Bar Ass’n 2019).

[11] Id.

[12] See, e.g., Katherine Snow Smith, What is an amicus brief, exactly? Let us explain, The Legal Exam’r, Nov. 5, 2020, https://www.legalexaminer.com/legal/what-is-an-amicus-brief-exactly-let-us-explain/ (citing one scholar in 2020 who estimates the price on an amicus brief at $40,000, and a practitioner who noted, “I’m aware of some that cost $60,000, $70,000, $80,000 or more…”); Kelly J. Lynch, Best Friends?: Supreme Court Law Clerks on Effective Amicus Curiae Briefs, 20 J.L. & Pol. 33, 58 (2004) (noting 2004 estimate from Sidley Austin Brown & Wood that “an amicus brief would run approximately $50,000 today”).

[13] Any data entry or coding errors are my own. Amicus briefs exclude briefs filed by the United States or the Solicitor General.

[14] See, e.g., Adam Bonica, Adam Chilton, & Maya Sen, The “Odd Party Out” Theory of Certiorari (Harv. Kennedy School Working Paper, Paper No. RWP20-020, 2023), https://scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/msen/files/odd-party-out.pdf.

[15] See William Baude, Foreword: The Supreme Court’s Shadow Docket, 9 NYU J.L. & Liberty 1 (2015).

[16] The Supreme Court Database, Wash. U. L., http://supremecourtdatabase.org/documentation.php (last visited Jan. 5, 2024). The Codebook for the Database explains the methodology. See http://supremecourtdatabase.org/_brickFiles/2022_01/SCDB_2022_01_codebook.pdf. For instance, “liberal” in “issues pertaining to criminal procedure, civil rights, First Amendment, due process, privacy, and attorneys” include pro-affirmative action, pro-female in abortion, pro-person accused or convicted of crime positions; and “conservative” the opposite. In tax cases, “liberal” positions are pro-United States and “conservative” pro-taxpayer. In an occasional case where the outcome was “unspecifiable,” I supplied coding. For instance, in Frank v. Gaos, 139 S. Ct. 1041 (2019), the parties briefed the case, amici filed briefs in support, and the Court later asked for briefing on another issue and decided the case on that basis.

[17] See id. (“Hence, if you are analyzing issue, legal provision, or direction (liberal, conservative, indeterminate), keep in mind that the data pertain only to the first of what may comprise an additional number of issues or legal provisions for any given case.”). See also Michael Heise, Beyond Replication: A Few Comments on Spruk and Kovac and Martin-Quinn Scores, 61 Int’l Rev. L. & Econ. 1, 2 (2020); Todd E. Pettys, Free Expression, In-Group Bias, and the Court’s Conservatives: A Critique of the Epstein-Parker-Segal Study, 63 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (2015); Aaron-Andrew P. Bruhl, Measuring Circuit Splits: A Cautionary Note, 3 J. Legal metrics 361 (2014). And some cases may not necessarily code as “liberal” or “conservative” to a popular understanding. For instance, a case construing Article III standing narrowly may be coded as “conservative,” but the outcome of the case may appear to be a liberal victory. See California v. Texas, 141 S. Ct. 2104 (2021). Likewise, a case involving the free exercise of religion may be coded as “liberal,” but the outcome of the case may appear to be a conservative victory. See Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berru, 140 S. Ct. 2049 (2020).

[18] There are admittedly alternative ways of determining ideological positions through textual analysis, and it is possible to explore ideology in texts using large language models or other “big data” methods, too. See, e.g., Michael Laver, Kenneth Benoit, & John Garry, Extracting Policy Positions from Political Texts Using Words as Data, 97 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 311 (2003); Justin Grimmer, We Are All Social Scientists Now: How Big Data, Machine Learning, and Causal Inference Work Together, 48 Pol. Sci. & Pol. 80 (2015).

[19] The 2021 Am Law 100: Ranked by Gross Revenue, Am. Law., Apr. 20, 2021, https://www.law.com/americanlawyer/2021/04/20/the-2021-am-law-100-ranked-by-gross-revenue/. Any firms that merged during this period of time were coded together.

[20] In the relatively rare event that more than one Am Law 100 law firm was on the brief, I counted each law firm separately, as if co-authors on an article. This means the total of amicus briefs “signed by” large law firms is a slightly larger total than the raw number of amicus briefs filed.

[21] See supra notes 6 and 12 and accompanying text.

[22] See supra note 12.

[23] For instance, political parties are tax-exempt organizations in the United States, but political parties spend significant money on litigation costs. See, e.g., Derek T. Muller, Reducing Election Litigation, 90 Fordham L. Rev. 561 (2021). These and other complexities in using “likely pro bono” as a proxy for pro bono work likely overstate some of the work. There are also many non-profit trade organizations that represent the interests of groups like commerce, petroleum, manufacturers, lawyers, and doctors. I coded them all as “likely pro bono” and did not try to distinguish between types of non-profit organizations. I did, however, run a rough estimate to see if pulling out these organizations, which were about one quarter of all “likely pro bono” amicus briefs in this period, would change the results. The positions of briefs of these organizations did tend to skew more conservative than other “likely pro bono” organizations, likely because “pro-business” positions are coded “conservative,” see supra note 17. That means the overall analysis might skew more in the “liberal” direction if business organizations were excluded.

[24] In consolidated cases, some briefs are filed in one or another case, and some in both. I ensured briefs were only counted once, but I took the larger cases and consolidated them even if briefs were only filed in one or another case (e.g., Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek).

[25] See Aaron-Andrew P. Bruhl & Adam Feldman, Separating Amicus Wheat from Chaff, 106 Geo. L.J. Online 135, 135 (2017) (noting that cases with thirty or more amicus briefs are “no longer particularly rare”). Cf. Kearney & Merrill, supra note 1, at 831 (identifying thirty-four cases that triggered twenty or more amicus briefs in a fifty-year period between 1946 and 1995).

[26] One way to determine salience might be popular salience ascertained by media coverage. See, e.g., Tom S. Clark, Jeffrey R. Lax, & Douglas Rice, Measuring the Political Salience of Supreme Court Cases, 3 J.L. & Cts. 37 (2015). Other ad hoc measures include the CQ Press “Key Cases,” identified by CQ Press authors as the “most important in American constitutional and political history,” see Supreme Court Collection, CQ Press, https://library.cqpress.com/scc/static.php?page=about&type=public (last visited Jan. 5, 2024); and Segal-Cover scores, which focus on “civil liberties and civil rights” issues, see Jeffrey A. Segal & Albert D. Cover, Ideological Values and the Votes of U.S. Supreme Court Justices, 83 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 557 (1989).

[27] Looking at the total number of briefs filed could be a more challenging measure to use across eras, as amicus practice has grown significantly, but in this limited window of time it should offer a comparable measure regardless of the term in which the Court heard the case. See also Ryan Salzman, Christopher J. Williams, & Bryan T. Calvin, The Determinants of the Number of Amicus Briefs Filed Before the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953-2001, 32 Just. Sys. J. 293 (2011).

[28] 142 S. Ct. 2228 (2022).

[29] 140 S. Ct. 1731 (2020).

[30] 142 S. Ct. 2111 (2022).

[31] 141 S. Ct. 1868 (2021).

[32] 140 S. Ct. 2103 (2020).

[33] See also Bruhl & Feldman, supra note 25, at 146–47 (noting that high profile cases attract more amicus briefs of “quite different kinds,” a qualitative and quantitative increase in briefs).

[34] Indeed, at least one prominent law firm dispute over the appellate litigation positions of one its attorneys appears to have been driven by client concerns. See supra note 7 and accompanying text; Jess Bravin, Winning Lawyers in Supreme Court Gun Case Leave Firm, Wall St. J., June 23, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/winning-lawyers-in-supreme-court-gun-case-leave-firm-11656026132 (“After recent mass shootings, other Kirkland clients began expressing reservations over the firm’s work for the gun movement, a person familiar with the matter said. Kirkland ‘started getting a lot of pressure post-Uvalde, hearing from several big-dollar clients that they were uncomfortable,’ this person said. ‘Several partners agreed that they should drop that representation.’”).

[35] An initial comparison of some of my previous research on law firm political contributions with the data here shows some relationship between political giving and amicus contributions. See supra note 9. That said, most firms mostly contribute to Democratic political candidates and mostly support liberal positions in likely pro bono amicus briefs, which deserves separate inquiry in later research.

[36] See Larsen & Devins, supra note 2, at 1921–24 (describing parties “wrangling” amicus briefs to include coveted attorneys on brief).

[37] See id. at 1919–26 (describing the “wrangling” and “whispering” of organized amicus brief practice).

[38] Cf. supra note 12 (approximating a financial value for drafting amicus briefs).

[39] Additionally, the skew of briefs could be overstated in one direction or another if some categories labeled “likely pro bono” are not actually pro bono but on behalf of paying clients. See supra note 23 and accompanying text.

[40] See, e.g., Larsen & Devins, supra note 2, at 1940–41 (identifying varying benefits to the law firm in filing amicus briefs). See also Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier, Quality Over Quantity: Amici Influence and Judicial Decision Making, 107 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 446 (2013) (noting heterogenous influence of outside groups in amicus brief filing on the United States Supreme Court).