On November 28, 2008, New York Giants wide receiver Plaxico Burress accidentally shot himself in the thigh with an unlicensed handgun while partying at a New York City nightclub. Beyond the poor judgment of the incident itself was the short-sightedness of the team’s response to it, which demonstrated just how inadequate problem-solving can be when conducted without the use of a structured approach.

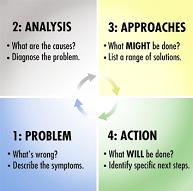

The major flaw lay in failing to properly diagnose the problem and failing to sufficiently brainstorm possible solutions. In this way, the Giants ended up treating the symptoms of the problem rather than the problem itself. Deliberately following a model such as the Four Quadrant Tool for problem-solving* would have helped the team avoid the classic misstep of jumping straight from describing the symptoms of a problem (step one) to generating an action plan going forward (step four).

.

The Giant Mistake

They Started with Step One…

First, the team identified the major implications associated with the shooting, the most important being distractions and a potential loss on investment.

Distractions. The Burress situation had the potential to distract the Giants from its ultimate goal – winning football games. Controversies like this one often cause stress for both players and coaches alike, as questions from the media infest the locker room, shifting focus away from preparation and execution. Specific examples from the recent past include other superstar wide receivers like Terrell Owens in Philadelphia and Randy Moss in Oakland, whose off-field antics eventually outweighed their on-field heroics, dragging teams with huge potential and previous success into the abyss of mediocrity.

Potential Loss on Investment. Initial reports indicated that Burress’ self-inflicted injury would have sidelined him for approximately four to six weeks. On top of that, he now faces criminal charges in the State of New York that could cost him 3½ to 15 years in jail, not to mention a possible suspension from the NFL, based on its stern player-conduct policy. In addition to mitigating any distractions caused by the incident, then, the Giants also wanted to do anything they could to avoid fulfilling a huge contract for a player who might not be able to produce any value for them.

…And Skipped to Step Four

To alleviate these symptoms, the Giants jumped straight to the most obvious solutions, first attempting to cover up the incident and then simply suspending Burress when those efforts proved unviable.

Attempted Cover-Up. The NFL as a league and each of its teams individually employ their own security staff called NFL Security, ostensibly to help players manage situations involving off-field incidents. But many insiders – including Dan Moldea, author of the book “Interference: How Organized Crime Influences Football” – believe that the real purpose of this security detail is to cover up player misbehavior in order to avoid bad publicity. Although league policy does not explicitly prohibit players from contacting the police in matters like this, it strongly encourages players to contact team officials as soon as possible and let them handle the process.

There have been a number of instances in the recent past in which NFL Security has successfully protected their own in situations like this. In 1989, Cincinnati Bengals star running back Stanley Wilson overdosed on cocaine the night before the team was to appear in the Super Bowl. Cincinnati Police Chief Larry Whalen, at the time moonlighting as security detail for the Bengals, found Wilson shaking in his hotel room bathroom with drugs in his hands. Whalen turned the drugs over to the NFL rather than the police and hid Wilson in another hotel until he had recuperated. In 2004, friends of Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick stole the Rolex of a security screener at the Atlanta airport. Billy Johnson, the NFL trouble-shooter assigned personally to Vick, allegedly offered the security screener $1,000 to keep the quarterback’s name out of the ensuing police report.

In this particular instance, Burress and teammate Antonia Pierce, who was with Burress at the club, followed league custom, immediately contacting Giants official Ronnie Barnes instead of the police. Barnes advised them to go to New York Presbyterian Hospital, which employs team physicians, and Burress admitted himself under a fake name. Although state law requires that hospital administrators report gunshot wounds to the cops, nobody – not even hospital personnel – notified them until eight hours after the shooting took place. In fact, the police only learned about the incident only through reports on ESPN. In the time since, the police as well as the mayor of New York have been highly critical of the NFL for withholding information and witnesses and generally hampering their investigation.

Despite these efforts, covering up the matter completely was no longer a possibility.

Suspending Plaxico. So the Giants quickly moved to their plan B. Since Burress was going to be physically unable to perform for at least the remainder of the regular season, the team figured out a way to rid themselves of their contractual obligation to him for that period of time. While lucrative, Burress’ $35 million contract includes no guaranteed money. By placing him on the non-football injury reserve list, then, the Giants were able to avoid paying Burress the remaining $1.823 million owed to him for the 2008 season. This roster move also enabled the Giants to defer their decision on whether or not to release him for next season until they learn more about this legal fate. Burress is scheduled to return to court on March 31 after being charged with two counts of illegal possession of a firearm and released on $100,000 bond.

However, the strategy also came at a price. As per league rules, placing Burress on the non-football injury reserve list meant that he would be unavailable during the post-season as well, even if his injury had fully healed in time to play.

The Result

As it turned out, the Giants’ first (and only) playoff game took place exactly six weeks and two days after the shooting occurred. It’s unclear where Burress is in the healing process right now, but if the initial prognosis alluded to above was correct, he would have been ready to play this past Sunday.

Although his personal performance up to the incident was mediocre, it’s clear that the Giants as a team suffered without him. In the twelve games before Burress was suspended, quarterback Eli Manning completed 64% of his passes and had a passer rating of 94. In the five games since, Manning completed 50% of his passes and had a passer rating of 63. Not to mention the glaring 11-1 record beforehand compared with the 1-4 record afterwards. The mere fact that Burress demanded double coverage opened up the running game and freed up other receivers, even if he himself wasn’t making big plays.

But when the Giants needed him most, in an elimination round playoff game in which he theoretically could have suited up if he hadn’t been suspended, he was nowhere near the stadium.

A Better Gameplan

The Giants would have been likely to achieve better results had they taken a more structured approach to problem-solving. By following the guidelines of the Four Quadrant Tool, they should have diagnosed the causes of the problem and brainstormed a whole range of possible solutions before deciding on an action plan going forward.

Step Back to Step Two…

The real problem here runs much deeper than simply the ramifications of the incident or even the incident itself. The real problem rests on the intersection of at least three major issues that permeate all professional sports: fear for one’s life, an inflated sense of entitlement and poor decision-making skills.

Fear for One’s Life. Pro athletes see themselves as targets, and rightly so. In some cases, the targeting is a result of their own doing. Flaunting wealth has a way of driving jealous people crazy. In other cases, it’s simply a virtue of being in the spotlight. Either way, there have been a number of incidents in the recent past that justify the kind of fear that causes guys like Burress to carry a weapon when they go out. Just last season, almost a year to the day before Burress accidentally shot himself, Washington Redskins safety Sean Taylor was murdered in his own home by armed burglars. And only three days before the Burress incident, on November 25, Giant teammate and fellow wide receiver Steve Smith had been robbed at gun point near his home in Clifton, NJ.

Inflated Sense of Entitlement. It’s no secret that many pro athletes view themselves as above the law. And the public is as much to blame for this attitude as anyone. We treat athletes as super-human and often look the other way when they misbehave. In this particular instance, for example, security at the Latin Quarter nightclub actually checked Burress for weapons, but allowed him entry with his gun anyway because he told them he was carrying $5,000 in cash and needed it for protection. In this way, star treatment got Burress into trouble simply by enabling his criminal behavior. But more than that, his inflated sense of entitlement led him to make a conscious decision – that simply because he is a pro athlete, he could ignore the law that requires individuals to register their handguns and prohibits them from concealing any loaded weapon at all.

Poor Decision-Making Skills. On top of all of this, pro athletes have the reputation as a group of simply making poor choices. Maybe it’s unfair to be critical in this respect. Perhaps they don’t make any more mistakes than the average person does. But because their actions are constantly being examined under a microscope, any mistake they do make is magnified. As a result, they should at the very least consider the consequences of their actions more carefully than the average person. In this particular instance, Burress chose to put himself in a situation that even he considered dangerous enough to carry a gun. I’m not saying that the guy shouldn’t have a social life, but he needs to have enough common sense to stop himself from going to sketchy clubs with huge sums of cash.

…And then Move to Step Three…

Once the true causes of the problem have been articulated, the Giants should have brainstormed every possible solution that might work to address them. In a real problem-solving situation, of course this list should be exhaustive, if not endless. But for purposes of this discussion, I will limit the ideas to a just few, for illustrative purposes only.

Public Acknowledgement. The easiest thing that the Giants could have done in the aftermath of the Burress situation would have been to simply acknowledge that there are fundamental problems in the NFL that go beyond the actions of one reckless individual and that they were committed to working with the league to help address those issues.

Bonuses for Good Citizenship. One way to address the fear factor that many athletes (including Burress) experience would be to make these athletes more relatable to the common man. The more a professional athlete gives back to his community, for instance, the less motivated individuals within that community will be to target him for crime or violence. Clearly, there will always be lawless criminals lurking about, seizing on opportunities to make a couple bucks through a robbery. But to the extent that the professional athlete can create goodwill within his community, he is that much less likely to be victimized. In response to the Burress incident, the Giants could have instituted a team policy or, better yet, worked with the NFL to develop a league-wide policy that offers bonus compensation to those players who exemplify good citizenship. Rather than simply punishing players for bad behavior – a practice that has proven somewhat ineffective – the team and/or the league could have incentivized good behavior instead.

Penalties for Coaches and Teams. It’s unrealistic to suggest that anything the Giants do now could have a huge impact on the entitlement issue anytime in the near future. At this point, the attitude is so ingrained that it is generational. However, the team can take greater responsibility for it and manage it to some extent. Yes, professional athletes are grown men, and ultimately they will do as they please. But holding coaches or even the organization itself accountable for player misbehavior will force the higher-ups to be more diligent about their players’ actions. If the Giants had fined head coach Tom Coughlin for the Burress incident, for instance, he’d become even more of a disciplinarian than he already is known to be. In the end, players wouldn’t be able to get away with the kinds of things they’re used to getting away with, perhaps even going to nightclubs with illegal weapons. If the Giants had gone even further, to perhaps voluntarily forfeit their next game, they could have sent the message that player actions have consequences that go beyond simply their own livelihood.

Buddy System. One cutesy way to address the frustrating phenomenon of poor decision-making would be to institute a buddy system. Since most off-field incidents occur at nightclubs, the Giants could have mandated that no player is allowed to go to a club without another teammate present. If either player ends up in trouble with the law, both players would be penalized, no matter who was involved. Such a policy would promote self-policing and perhaps lead to better decision-making overall.

Renegotiating Burress’ Contract. The Giants could have avoided paying the remainder of Burress’ 2008 salary simply by renegotiating his contract. There really was no reason to place him on the non-football injury reserve. Considering his alternatives, Burress would have had no choice but to agree to pretty much anything the Giants offered. And this way, he would have been available for the playoffs should he have recovered in time rather than forced to missed the game because of non-football injury reserve rules.

…Before Finally Arriving at Step Four

At this point, the ideas generated in step three should have been evaluated and clarified while considering factors such as administrability, efficiency and financial feasibility. Committing to an operational subset of the universe of possible solutions generated by this kind of structured approach would have resulted in a much more sensible action plan that had the potential to treat the problem itself, not just its symptoms.

Conclusion

In this particular problem-solving scenario, employing a structured approach might not have produced vastly different results in the short term. Because Burress was injured and unavailable for at least the remainder of the regular season, the team might have sputtered in its final weeks no matter what approach they took. But consider for a moment the long term. Because the Giants failed to address the underlying causes of the Burress situation (fear, entitlement, poor decision-making), its symptoms are likely to recur at some point soon down the road, perhaps even with a different stimulus altogether.

Indeed, you don’t need Burress for bullets to fly.

* Four Quadrant Tool for Problem-Solving, developed by the Harvard Negotiation Project. See “Circle Chart” in Robert Fisher and William Ury, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (1983).

Michael Blank is an associate at Insight Partners, where he focuses on negotiation and effective communication training for corporate clients around the world. His other facilitation work includes skills training in academic contexts, including Harvard Law School and the University of Massachusetts. Prior to law school, Mr. Blank was an analyst in the leveraged finance group at Bears, Stears & Co. in New York. Mr. Blank earned his B.A. in economics from Dartmouth College and his J.D. from Harvard Law School.