Although the issue has not yet gained the prominence of its Iranian analogue, it is essential to begin conducting a sober analysis of whether the benefits of negotiating with the Taliban outweigh the costs. While there are many negotiations relevant to the Afghan War—between the U.S. and its NATO allies, between the U.S. and the Afghan and Pakistani governments, and between the Pakistanis and the Taliban—this paper will focus on whether the United States, together with its allies in Kabul or NATO, should negotiate with the Taliban.

To bring a coherent logic to the complexities of this cost-benefit analysis, I will apply the decision-making framework described by Professors Mnookin and Blum in their article “When Not to Negotiate” and elaborated upon in Professor Mnookin’s forthcoming book, Bargaining with the Devil. This framework focuses the inquiry on five key issues: 1) the parties’ prioritized interests, 2) their best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), 3) potential negotiated outcomes, 4) the probability of implementation, and 5) the direct and indirect costs of negotiation. The framework then focuses on the related considerations of legitimacy and morality. Mnookin and Blum argue that while we should not always “bargain with the devil,” our ingrained biases often lead us to reject negotiation prematurely, and we should therefore establish a rebuttable presumption in favor of negotiating.[1] With this in mind, I conclude that although it may indeed be too soon for direct talks between the U.S. and the Taliban, it is not too soon for indirect talks to probe the Taliban’s interests and to seek a path to a zone of possible agreement (ZOPA) and a mutually beneficial outcome.

The Current Context for Negotiations

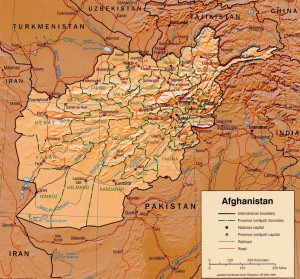

As President Obama orders more troops to Afghanistan, the Taliban are making strategic gains in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.[2] In February, even while U.S. drones stepped up attacks on Al-Qaeda and Taliban militants in the tribal areas in northwestern Pakistan, the Taliban effectively subdued the Pakistani military in the Swat Valley. This demoralizing defeat prompted Islamabad to negotiate an agreement with the Taliban, effectively ceding a large swath of territory in central Pakistan, allowing the Taliban to impose Sharia law and institute measures that included closing girls’ schools, banning music, and installing “complaint boxes for reports of anti-Islamic behavior.”[3]

Even so, preliminary talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban have also taken place, albeit indirectly.[4] But the Taliban claim that they will refuse to negotiate until all foreign forces are withdrawn from Afghanistan.[5] Meanwhile, a State Department spokesman indicated that the Karzai government had set its own conditions that reportedly included “a renunciation of violence, acceptance of Afghanistan’s democratic Constitution and a repudiation of Al Qaeda—all terms the Taliban leadership has rejected.”[6] Another State Department official referred to preconditions including the exclusion from talks of any member of the Taliban linked to 9-11 and the exclusion from the agenda of proposals concerning power sharing or land swaps.[7]

Into this morass of positional bargaining now steps Richard Holbrooke, a veteran diplomat and President Clinton’s chief negotiator during the Bosnian War. In contrast to his mediation in Bosnia, his “Afpak” assignment promises a new breed of interlocutors: a loose coalition of Taliban and other militant groups, operating largely behind the Pakistani border, and perhaps unwilling or unable to implement any long-term agreement. With so much uncertainty, how to decide whether to negotiate with the Taliban?

The Parties’ Prioritized Interests

As opposed to the wide-ranging interests involved in the Iranian case (for example, nonproliferation, containing oil prices, and protecting Israel), in Afghanistan the U.S. is interested primarily in maintaining its own security at the lowest possible cost in blood and treasure. Related interests include setting a strong precedent in the wider fight against terrorism, and providing for the development of Afghanistan in a manner that improves America’s international standing and minimizes the risk that Afghanistan later backslides into a failed state.

The Taliban, too, have relatively simple interests. First, they have a strong interest in survival—as an organization and as individuals. Second, the Taliban and its members have an interest in retaining influence and prosperity following the ultimate withdrawal of foreign forces. This interest in power extends to a financial interest and an interest in good public relations.

The Parties’ Alternatives

Since the parties already find themselves in the midst of war, the basic alternatives to a negotiated agreement are the continuation of war or an American withdrawal. Theoretically, the Taliban could surrender or be destroyed, but these outcomes seem relatively unlikely; as General Petraeus has noted, “You don’t kill or capture your way out of an industrial strength insurgency.”[8] It would seem that time is on the side of the Taliban regarding BATNAs, as no foreign power has ever successfully maintained control of Afghanistan or imposed central rule.[9]

To improve its BATNA, the U.S. must fill the power and legitimacy vacuum in Afghanistan in which President Karzai is essentially reduced to the role of the corrupt “mayor of Kabul.”[10] Before the U.S. withdraws under any scenario, the power of the Kabul government must be increased, warlords must be supported, or regional powers must step in to fill the vacuum. Clearly, the most acceptable alternative is to empower Kabul to legitimately govern the country as a whole, but it remains to be seen if this will be possible.

Potential Negotiated Outcomes

It appears that a ZOPA will emerge only when the Obama administration determines that the security and international standing of the U.S. would not be unduly threatened by allowing a critical mass of “reconcilable” Taliban members to maintain some measure of power in Afghanistan. Determining whether U.S. security and reputational interests would be unduly threatened by such a negotiated outcome entails a balancing test between those interests and the administrations’ other interests, including financial and domestic political interests.

The extent of both the critical mass of Taliban reconcilables and the power that they maintain depends largely on the parties’ evaluation of their BATNAs at the time of the negotiation. If negotiations were to occur now, President Obama would be playing with a weak hand. The Taliban’s recent gains, the ubiquitous perception of the incompetence and corruption of the Karzai administration, and the worldwide financial crisis all signal that the Taliban’s BATNA is superior to that of the U.S. and its allies. If it were to set an early deadline for a negotiated agreement with the Taliban, the U.S. could expect to obtain little more than a “decent interval” between a withdrawal and Taliban recidivism—perhaps by providing sanctuary to Al-Qaeda or denying women education and medical care.[11] Significantly, the U.S. would probably have to offer the Taliban some degree of autonomy from Afghanistan’s central government.

However, if negotiations were to occur (or continue) beyond a short-term time horizon, the U.S. could potentially change the game by improving its BATNA and reducing the attractiveness of the Taliban’s BATNA. Under such negotiating circumstances, the U.S. may succeed in splitting off a critical mass of “reconcilables”—i.e. dissident Pashtuns affiliated with the Taliban—from the “irreconcilables”—a core of extremist ideologues. Theoretically, if this “divide and conquer” strategy were to work, the U.S. may need only “conquer” the irreconcilables, while paying off the reconcilable Pashtuns as it did with the Sunnis in Iraq.

Implementation

Even if the Obama administration could negotiate a satisfactory agreement with the Taliban members it determined to be reconcilables, there is reason to doubt whether such an agreement could be implemented in Afghanistan. For example, New York Times correspondent Dexter Filkins explains that while Iraq is still a tribal society in which “a big bag of money” given to a tribal leader can effectively “deliver the tribe,” Afghanistan is a country that “has been at war for thirty years and has been decimated and atomized—old tribal networks have been completely attenuated.”[12] Similarly, Noah Feldman argues that, in contrast to the Iraqi tribal structure which was built by the British to deliver patronage, “Afghanistan’s tribes—a term that covers everything from large confederations to cousin-networks and extended families—are not natural vehicles for creating loyalty to a central government.”[13]

While many question whether the current split between Fatah in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza rules out any prospect of implementing an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement, Afghanistan’s fissures appear more numerous than those between the Palestinian factions. The fissures of most direct relevance to the issue of implementation are those within the Taliban reconcilables themselves. Is there anyone who can speak for the reconcilables as a whole and deliver their compliance with a negotiated agreement? At the very least, this hypothetical representative would have to be free of any direct link to the September 11 attacks.

The recent Pakistan-Taliban ceasefire agreement in Swat—evidently unacceptable in substance—also provides an example of the procedural challenges involved in attempting to peel reconcilables away from irreconcilables. There, the Pakistani government brokered the cease-fire agreement “with an aging Islamic leader, Maulana Sufi Muhammad,” viewing the negotiation “as a way to separate what it considered to be more approachable militants, like Muhammad, from hard-line Taliban leaders like Maulana Fazlullah, his son-in-law.”[14] Thus far, it appears that the Taliban have not implemented the terms of this agreement.[15]

Direct and Indirect Costs

In addition to the potential benefits of a negotiated agreement relative to the parties’ BATNA, it is also necessary to calculate the costs “incurred by the negotiation process itself, regardless of whether a deal is ultimately made.”[16] Since the U.S.’s BATNA is extremely unappealing, the costs of negotiating must reach a very high threshold to rule out negotiations, especially given Mnookin’s rebuttable presumption in favor of negotiating.

The direct costs of negotiating with the Taliban reconcilables include the time, money, and manpower spent in seeking out—perhaps even helping to consolidate—and then negotiating with the reconcilables. Even if Mr. Holbrooke is granted sufficient latitude to avoid conferring routinely with an overworked administration, presumably there are opportunity costs to pursuing a strategy of negotiation with the Taliban—as opposed to having his team focus on working with Pakistan, NATO allies, or the Afghan government. Direct costs would also include any information that may be disclosed to the Taliban during the negotiation. For example, if there were an American presence at the negotiating table while the U.S.’s BATNA remained unattractive, the Taliban may perceive that the U.S. has been weakened and ready to withdrawal.

The indirect costs of negotiating with the Taliban reconcilables include the signal it may send “behind the table” to U.S. allies and domestic constituents. If the Obama administration were to walk out on the negotiations, it may then face increased difficulty in convincing its allies and its constituents of the necessity to continue the war well into the future. In negotiating with the Taliban, the U.S. may also have to incur the indirect cost of setting a precedent that the U.S. will now “negotiate with terrorists.” To minimize this cost, the Obama administration could initiate negotiations secretly and ultimately rebrand its negotiation partners as “reconcilables,” “Pashtun rebels,” or Taliban “affiliates.” Also, as a toppled government, the Taliban may be distinguishable from, for example, hijackers, or purely non-state actors such as Al-Qaeda.

Questions of Legitimacy and Morality

Closely related to the indirect costs of the negotiation process are questions of legitimacy and morality. Mnookin and Blum note that “[p]roviding a counterpart with ‘a place at the table’ acknowledges their existence, and (to some degree) the validity of their interests and claims.”[17] The U.S. may indeed find it necessary to acknowledge the validity of the interests of some Pashtuns who have seen their relatives killed and property destroyed during the war, but it should be able to distinguish these cases from the extremism of the Taliban ideology. Alternatively, the U.S. could negotiate entirely through the Afghan government or try to keep its role secret.

A related concern is avoiding the perception that the U.S. is rewarding past bad behavior. But, in the words of Yitzhak Rabin, “You don’t make peace with friends, you make peace with very unsavory enemies”—enemies that have necessarily engaged in bad behavior in waging war against you.[18] Presumably, few states will emulate the Taliban in providing safe haven to terrorists simply because the U.S. may be expected to negotiate after seven years of war.

Conclusion: Should the US Negotiate with the Taliban?

The U.S. must pursue numerous strategies if it is to fulfill its objectives in Afghanistan: it must convince Pakistan to increase its pressure on the Taliban in the tribal areas, compel NATO allies to dedicate more troops to Afghanistan, and build the capacity of the Afghan government to provide much-needed services to its people in order to lure them back from the appeal of authoritarian stability. These strategies are not alternatives to a negotiated agreement, but rather complements to negotiating with the reconcilables. Barring total victory for the U.S. over a pervasive, locally-based force, the question is not whether we will negotiate with the Taliban, but when, under what circumstances, and with which members? It may indeed be too soon to push for direct talks with the Taliban because the conditions are not yet ripe to negotiate an acceptable outcome for the U.S., and serious costs may result. But it is probably never too soon for indirect talks, in order to feel out the Taliban’s interests and seek a path to a ZOPA—all while striving to increase bargaining power by improving the U.S.’s BATNA and decreasing the attractiveness of the Taliban’s BATNA.

Andrew Blandford is a joint degree student at Harvard Law School and the Harvard Kennedy School focusing on international law and international relations. He can be reached at ablandford@law.harvard.edu.

[1] Gabriella Blum & Robert H. Mnookin, When Not to Negotiate, in The ABA Negotiator’s Fieldbook, 101 (Andrea K. Schneider & Christopher Honeyman eds., 2006).

[2] Elisabeth Bumiller, General Sees Long Term for Afghanistan Buildup, N.Y. Times, Feb. 18, 2009, at A9.

[3] Jane Perlez and Pir Zubair Shah, Truce in Pakistan May Mean Leeway for Taliban, N.Y. Times, Mar. 5, 2009; Most recently, the Taliban have pushed farther south into Buner, finally encountering resistance from the Pakistani military. Carlotta Gill, Pakistan Says It Killed 50 Taliban in a Clash, but Residents Say Civilians Died, N.Y. Times, May 1, 2009, at A4.

[4] Last fall, an Afghan delegation attended a dinner hosted by the Saudi king in which Taliban affiliates were present. Soraya Sarhaddi Nelson, Hints Swirl, But Afghan-Taliban Talks Not Yet Reality, NPR, Oct. 20, 2008.

[5] Id.

[6] John F. Burns, Karzai Sought Saudi Help With Taliban, N.Y. Times, Sept. 30, 2008, at A12.

[7] Perlez & Zubair Shah, supra note 3.

[8] Robert Burns, Gen. David Petraeus leaves Iraq after 20 months, Huffington Post, Sept. 16, 2008.

[9] Dexter Filkins, No End In Sight In Afghanistan, NPR, Feb. 25, 2009.

[10] Id.

[11] Editorial, Salvaging Afghanistan, N.Y. Times, Feb. 19, 2009, at A30.

[12] Filkins, supra note 9.

[13] Noah Feldman, Fighting the Last War?, N.Y. Times, Nov. 28, 2008.

[14] Perlez & Zubair Shah, supra note 3.

[15] Carlotta Gall, Pakistan Says Islamic Court Fulfills Deal with Taliban, N.Y. Times, May 3, 2008.

[16] Blum & Mnookin, supra note 1, at 104.

[17] Id. at 107.

[18] Nicholas Burns, We Should Talk to Our Enemies, Newsweek, Oct. 25, 2008, at 40.

The New York Times: Talked to Death

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/08/opinion/08sherjan.html?ref=opinion

ForeignPolicy.com: Talking with the Taliban?

http://walt.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2009/05/08/talking_with_the_taliban

Very sound analysis on the options and scenarios for Afghanistan. Congratulations!

A very important dimenstion of the Afghan conflict that has implications for both the outcomes of negotiations and the in-effectiveness of the Afghan governanment, remains to be studied and acknowledged by analysts of the Afghan war. Afghanistan has continuously suffered from the consequences of an unresolved civil war that took place between 1992 and 2001. This war had three dominant features

a) Ethnically dominated groups caused significant harms and destructions not only to each other but to the communities that shared certain identity. b) neighboring countries were heavily involved in this war. c) Supporting communities became strongly involved or affected by this war and therefore established hatred for the other side.

1) Impact on governance: The remnants of this unresolved war is feeding into the serious fragmentations in the Afghan state (stealing the national cohesion badly required for achieving national objecives of the government), failing the civil service reform (continuation of corruption and ineffectiveness), forcing individuals and groups to use conspiracy as a means for dealing with concerns about (real or percieved) injustices related to the present and future and hatred and anger resulted from (real or perceived) injustices of the past. The outcry about injustices of the past goes 20 years bacl for Pashtoons and 250 years for non-Pashtoons.

Impact on War: the sequelae of the unresolved civil war also contribute to continuation of the armed conflict by strengthening a destructive synergy. The synergy among Al-Qaeda, Pakistan ISI+Army, Taliban ideologues, Taliban reconcilables, and Pashtoons in the South and East needs to be broken down before any negotiation to succeed. There is little or no work done to explore the Pashtoon grievances caused by the 9-year of civil the war. These grievance and claims of injustices in the government force many Pashtoon residents of Taliban-dominated provinces to support Taliban. Through my work and research, I am convinced that there are thousands of people in these communities who do not share the ideology of the Taliban but fully support them and listen to their preechings with serious interest. There is feeling among these Pashtoons that the Bonn peace deal brough a Victor’s peace by marginalizing Talib-Hekmatyar (associated with Iran-India dominance and Anti-Pakitani sentement) and give full control of the power to the Northern Alliance. They still perceive Karzai’s government as monopolized by groupings of the former Northern Alliance and claim that important decisions by Karzai are fully controlled by the former Northern Alliance. You will hear them saying that the Ministry of Interior, Defense and Intellegence agencies as well as most provincial and district governments are controlled by their enemy of the civil war while they (Pashtoons) suffer from bombing and the parties they one supported are labeled as terrorists.

If you dig deeper in and around the government, you will hear about the injustices inflicted by the Pashtoon dynasty of 1747 – 1977. You will learn about ttempts to keep monopoly/ control of the key section of the government as well as the sector of economy for legitimate fears and concerns. The former Northern Alliance is legitimate concerned about the coming of brutal Taliban and selfish-Hekmatyar who, they percieve, will definitely try to eliminate them. Therefore, to survive you have to become and keep powerful politically and economically. Two final points:

1. there is a SILENCE imposed by the dominant that is why there no public talk about this. The Afghan public learned in a hard way, how to survive under dictator regimes.

2. there is no meaningful systematic dialogue mechanisms to resolve the distrust, anger and hatred left by the civil war and to deal with concerns about current and future injustices through peaceful means.

Regards

Seddiq Weera

Peace activist, practictioner and researcher; currently Senior Policy Advisor to the Afghan Government

US shouldnt bargain with Taliban Devils. The US is reponsible for all activities of Taliban Devils where ever in the world. Taliban is production of US and his coillations. We strongly condem Talibans activities. Killing innocent peopels US should destory Taliban from Grass Root level. And being muslim i asure to all western countries that taliban has no concern with islam becoz islam is a mission not a religious. Islam is relejious of PEACE not an icon of Terrior. Please speared my massage all over the world. Dont blame Islam. Hate Taliban dont hate islam. Work for PEACE. Long live PEACE

Why is this viewed as a potential negotiation between the GIRoA and Taliban, rather than between the GIRoA and the people? Shouldn’t the negotiation be the GIRoA and people coming to an agreement on the terms of what the people want from the GIRoA (basic governance / less corruption) and what the GIRoA wants from the people (cooperation against the Taliban)?

The lessons of Iraq are not easily transposed onto Afghanistan, but one analogy that seems valid is that we negotiated terms of cooperation with the local communities/tribes/factions in Iraq against AQI and it seems that conditions are even more conducive to this approach in Afghanistan than they were in Iraq (see David Kilcullen, Counterinsurgency pg 160. Did anyone think for a moment that negotiating a power-sharing agreement with AQI would be feasible? Why is all the talk now only of GIRoA and Taliban negotiation, rather than GIRoA agents negotiating with local Afghan communities?